Suture techniques are an indispensable means to biologically sculpt the cartilage of the nose. Here the authors review their use in tip-plasty and present a 4-suture algorithm that allows for simple, complete control in sculpting the shape of all nasal tips in primary rhinoplasty. After a standard cephalic trim of the lateral crus leaving it 6 mm wide, one or more of the four suture techniques are applied. One of the newest techniques that has yielded excellent results is the hemi-transdomal suture, a variation of the conventional transdomal suture. This technique narrows the dome but also everts the lateral crus slightly to avoid concavities of the nostril rim. The 4-suture algorithm is useful in both the open and closed approaches. A more general use of sutures is described and referred to as the “universal horizontal mattress suture,” which can be applied to remove all unwanted convexities or concavities and can be used not only to straighten the cartilage but also strengthen it. This suture has applications for the crooked septum, the collapsed lateral crus (external valve), and the collapsed internal valve, as well as for converting ear cartilage grafts into straighter, stronger grafts than previously thought possible.

Controlling the shape of the nose in large part involves controlling the shape of the cartilages. Much of this control is obtained by excisional and grafting techniques. Scoring techniques are used less and less frequently, and in recent years and have been relegated to straightening crooked septal cartilages. It is clearly preferable to retain natural cartilage and make it conform to the desired shape, and also clearly better to minimize damage to the cartilage, which would even allow for the possibility of reversibility. Therefore, suture techniques to shape the nose have witnessed a dramatic increase since the early 1980s. In this article on suture techniques, 2 major aspects are discussed: (1) techniques that totally and unambiguously control tip shape, and (2) a general technique that is applicable to all cartilages in the nose when one wants to eliminate undesirable convexities or concavities.

Tipplasty

Before undertaking nasal tip shaping with suture techniques, 3 surgical tenets should be followed to obtain consistent and reproducible results: (1) use a model, (2) preserve a 6-mm strip of lateral crus, and (3) recognize the delayed effects of suture on cartilage.

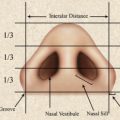

There are numerous angles and dimensions of the nose and its underlying framework to memorize. A surgeon can memorize several of them, but for the average plastic surgeon who performs the operation potentially only once a month, to become adept with all of them is a Herculean task. It is much easier to sculpt by using a model, which is a concept familiar to many commercial artists. A model is available ( Fig. 1 ) that is a reasonable prototype of what the normal sculpted tip should resemble if one expects the nose to look good when the skin is redraped. The model demonstrates that the tip is usually about 6 mm above the dorsum and that there is an angle of divergence formed by the middle crurae. It also demonstrates that there is (following most all tipplasties) an axis to the dome and that the axes of the domes separate to form an angle close to 90°.

By preserving 6 mm of lateral crus after the cephalic trim, one has a substantial piece of cartilage that is not likely to buckle or collapse ( Fig. 2 ), which also responds best to suture techniques. There is no need to remove more lateral crus when attempting to make the tip smaller or narrower.

Harris and colleagues demonstrated that the effect of a particular suture technique may change over time. This change may not occur until half an hour after the suture is placed. This effect is a subtle but real one, caused by the entire cartilaginous framework adjusting to the new tension provided by the suture. It is best at the end of the rhinoplasty procedure to have a final look at what the sutures have done and to make any minor adjustments as necessary.

Current rhinoplasty literature contains confusing nomenclature regarding the various suture techniques. The names used in this article represent the terms most commonly used by rhinoplasty surgeons. As for particular suture type, the authors tend to favor polydioxanone (PDS) whenever there is a question regarding soft tissue coverage. However, if coverage is not an issue, nylon is used. Although the study by Iamphongsai and colleagues indicated little difference between nylon and PDS in maintaining the curvature of cartilage in animals at 3 months, several surgeons are concerned that when PDS is absorbed, the cartilage may return to its original state.

There are a few algorithms for suture tipplasty. One of the best and most complete analyses is that by Guyuron and colleagues Daniel has also developed an outstanding algorithm that will serve any plastic surgeon well. Here, the authors present an abridged version that addresses the most common issues that the average plastic surgeon will encounter in practice, namely the 4-suture algorithm. However, not all 4 of the techniques are necessary in every patient.

Hemi-Transdomal Suture

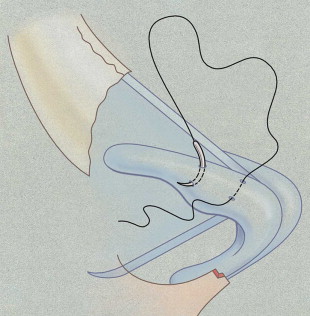

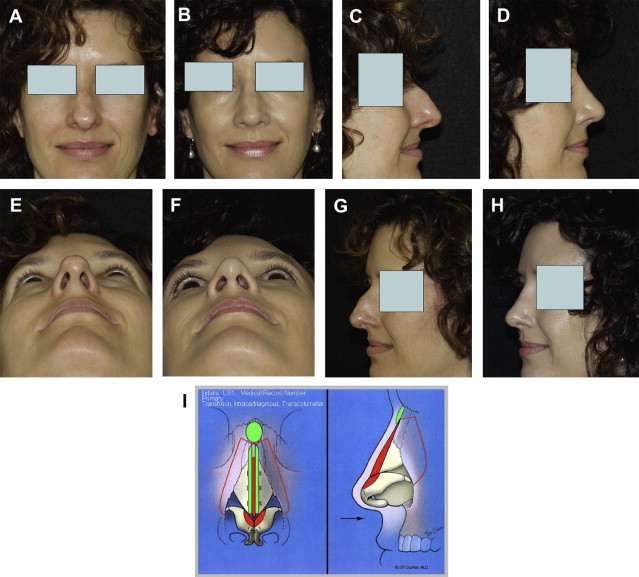

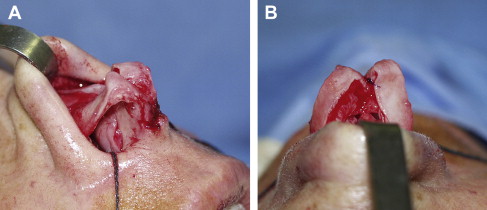

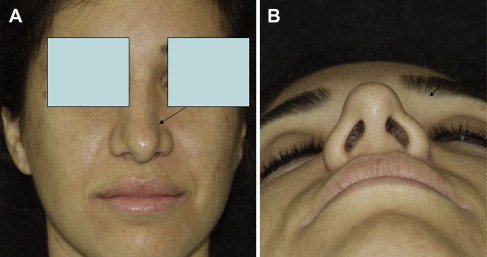

Perhaps the most important suture for the tip is that which controls the dome. The hemi-transdomal suture is a variation of the transdomal suture introduced by Tardy and colleagues for the closed approach and by Daniel for the open approach. The soft tissue deep to the dome is hyperinfiltrated with local anesthesia to prevent the suture from penetrating the vestibular skin. A 5-0 nylon or PDS is placed at the cephalic end of the dome ( Figs 3 and 4 ). The effect of this suture is to (a) narrow the dome, (b) evert the caudal border of the lateral crus, and (c) straighten the lateral crus (remove its convexity). Everting the lateral crus is an important concept. Without it the lateral crus may actually invert when a conventional transdomal suture is placed. The result ( Fig. 5 ) of inversion is a potential alar concavity that may then require a rim graft. In a few cases it will be necessary to add the conventional transdomal suture ( Fig. 6 ) if the actual dome width has not been reduced substantially. These fine adjustments are made after reflecting the skin flap in the open approach to see what the suture technique has done to the dome.

Interdomal Suture

The interdomal is a 5-0 PDS suture that brings together the 2 middle crura. The suture is placed approximately 3 mm posterior to the dome on the cephalic side of the middle crus ( Fig. 7 ). An interdomal suture keeps the domes together, enhances symmetry, and also provides strength to the overall tip complex. If one is attempting to create a major change in the symmetry or if the tips are very weak, it would be wiser to use a columellar strut.

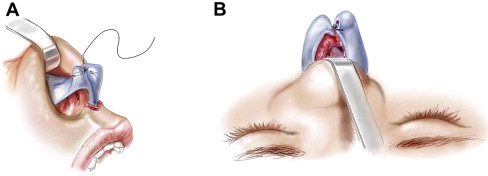

Lateral Crural Mattress Suture

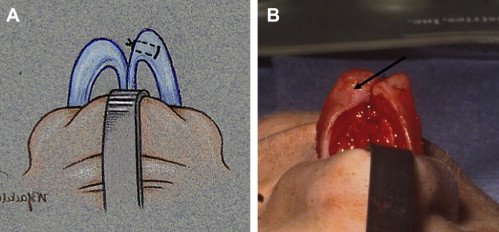

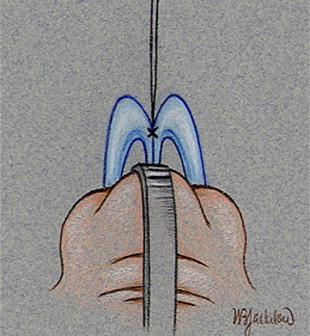

The lateral crus is often convex and often weak. The lateral crural mattress ( Figs. 8 and 9 ) suture addresses both deficiencies by correcting the convexity and strengthening the lateral crus. The suture is a 5-0 PDS or nylon applied at the apex of the convexity. After grasping the lateral crus at the apex of the convexity with a Brown Adson forceps, the needle is applied perpendicular to the long axis of the lateral crus as a bite is taken on one side of the forceps. The second bite is taken on the other side of the forceps (about 6 mm away from the first bite). The knot is not tied tightly, just tight enough to straighten the lateral crus. One also wants the lateral crus to remain straight when the weight of the skin flap is draped over it. To tell if the lateral crus is sufficiently stiff and will remain straight, it is helpful to apply an index finger to the dome and push down (in a posterior direction) and observe if a bulge (convexity) develops in the lateral crus. If a bulge develops, one or more lateral crural mattress sutures should be applied. It is often necessary to apply 2 or 3 lateral crural sutures to achieve the desired result. Of note, each suture supplies more strength to the lateral crus, and the effect is additive. Fig. 10 exemplifies the effectiveness and power of the hemi-transdomal and lateral crural mattress sutures.