A GLOBAL APPROACH FOR THE COSMETIC AND

PERSONAL CARE INDUSTRY

Editor’s Overview

Alban Muller (President, Alban Muller Group)

In the cosmetic world, we have seen “the green wave,” then the “organic tide,” and now “the eco-responsibility tsunami.” Do we have to consider that this wave will go by, allowing a new wave to come in? Like the ocean, waves come and go; some larger than others. At the time of this writing, we choose to consider that this eco-responsibility tsunami is probably more in line with various other converging evolutions and will rise and fall as previous and future waves. Since we must surf this wave or lose our customers, let us consider some important current parameters:

- • The first and most important parameter we are all faced with is the rapid expansion of humankind, which, in the last century, has multiplied our numbers on this planet by a factor of four. This sobering statistic leads us to the perspective of a humanity numbering 9 billion people in the next few decades. As we anticipate this incredible increase, there will inevitably be an increasing collective pressure on the Earth’s resources, thereby leading to concerns about their availability. Thus, renewability becomes a key issue and concern in the whole industrial process.

- • The second important parameter is that consumers don’t expect the same things from companies that supply their wants and needs any more. Not only do they want good value for their money, but they also expect that companies respect some values such as: the comfort of their employees, the offer of equal opportunities, and consumer safety along with an increasing respect for the global environment. For example, large U.S. distribution companies have recently embarked on programs to ban various chemicals suspected of being harmful to people or the environment.

When combined, these facets compel the formation of a new management approach that needs to show increased concern for the people and the planet, while not forgetting about profits. The only way to maintain an appropriate balance of these parameters is to take a better look at our products and how we produce them. By doing so, we can be innovative while finding new and economical ways to create new products with less impact on our environment.

As we explore these ideas in this part of Harry’s Cosmeticology, 9th Ed., one important observation emerges:

What we see is that eco-conception can bring innovative concepts, themselves generating new approaches and new technologies.

The various articles in the section show two major points of view and some proactive pathways to achieving our goals.

- • The first pathway consists of perfecting the existing industrial practices in order to reduce their global impact and produce better products (natural extracts and ingredients), which also results in superior performance when compared to their synthetic counterparts.

- • The second pathway involves an exploration of the kinds of new technologies that could be introduced to allow us to benefit from natural molecules, even by way of emerging biofermentation technology.

It is obvious that all these efforts have the potential to create the new “greener economy,” which in turn could be a source of technological progress.

Part 12.0 A Global Approach for the Cosmetic and

Personal Care Industry

Editor’s Overview

Alban Muller (President, Alban Muller Group)

Part 12.1 Defining Sustainability and how it changes

the innovation process

Author Jamie Pero Parker (Innovation Manager, RTI International) and

Phil Watson (Technology Commercialization

Manager, RTI International)

12.1.1 Sustainability—a critical business issue

12.1.2 Innovation is a critical but challenging

component of any sustainability strategy

a. The concept of open innovation (OI)

b. Open innovation and sustainability

are synergistic

12.1.3 Integration of sustainability principles into

innovation practices is evolutionary

a. Six key traits of sustainable companies

Part 12.2 A Botanist’s view of Sustainability:

Use or Abuse in the Personal Care Industry?

Author Michael J. Balick (Vice President of

Botanical Sciences, Director of the Institute of

Economic Botany, New York Botanical Gardens)

12.2.2 What happens once you find a species of interest?

1. Accurate identification of botanicals

3. Truthful representation of the local uses

of the plant in marketing efforts

4. Making sure the environment is not

degraded as a result of harvesting botanicals

5. Ensuring that local communities are not

negatively impacted by the harvest of the plant

12.2.3 Sustainable production of wild-harvested products

Part 12.3 The Herboretum Network for promoting local

cultures and biodiversity

Author Geneviéve Bridenne (CIO, Alban Muller Group)

a. An area of reflection, a scientific and

natural approach

b. An area of protection, a long-term commitment

to the protection of plant resources

Part 12.4 The advantages and potential contribution of local

cultures for carbon footprint reduction

Author Jean-Marc Seigneuret (Technical Director,

Alban Muller Group)

12.4.2 The use of plants in cosmetics

d. Good agricultural practices

a. Conventional farming (sustainable farming)

12.4.6 Initial post-harvest processing

Part 12.5 Cosmetic ingredients from plant cell cultures:

A new eco-sustainable approach

Author Roberto Dal Toso ( R&D Manager IRB SpA)

12.5.2 Traditional methods of botanical sourcing

12.5.3 Basic Parameters Influencing Extract Quality

12.5.4 Advantages of plant cell cultures:

the new alternative

12.5.5 Sustainability of the biotechnological approach

12.5.6 Phenylpropanoids: structure, metabolism,

and functions in plants

12.5.7 Standardization, Safety, and New Possibilities

12.5.8 Bioactive properties of PP for cosmetic applications

Part 12.6 Eco-responsibility applied to plant extraction

Author Alban Muller (President, Alban Muller Group)

12.6.1 Sourcing the plant raw material: Cultivation is key

12.6.2 Transforming the plant into a “drug” to become a cosmetic extract raw material

a. The traditional extractions

d. The eco-responsible steps around extraction

e. After extraction and concentration: Drying

12.6.4 An eco-responsible extract

12.6.6 The GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) parameter

12.6.7 Eco-responsibility applied to formulation

2. Vegetable oil and vegetable Oil esters

Part 12.7 The industrial frame: Concrete, green solutions

for production and waste management

Author Alban Muller (President, Alban Muller Group)

12.7.2 Water and biodiversity gardens

An original innovation: Restoring wetlands in

industrial areas

c. The return of animal biodiversity

d. A sensory environment, conducive to awareness

PART 12.1

DEFINING SUSTAINABILITY AND HOW

IT CHANGES THE INNOVATION PROCESS

Authors

Jamie Pero Parker (Innovation Manager, RTI International)

Phil Watson (Technology Commercialization Manager, RTI International)

ABSTRACT

Innovation will be essential to addressing the increasingly critical sustainability challenges companies face, such as limited natural resources, energy constraints, and consumer demand. To address these emerging business drivers and meet the green demands of consumers, many companies are introducing sustainability practices into their businesses. These practices require companies to measure success not just monetarily, but also by the cost to the people who make the goods, the impact of goods and services on surrounding communities, and the price paid by the environment.

Once viewed as a fleeting consumer trend, sustainability is now seen as a new business paradigm. This chapter presents an overview of concepts that are essential to the continued growth and effective product generation for cosmetic and personal care products to compete effectively in this changing world. Innovation is essential to addressing these critical sustainability challenges that are reshaping industries and supply chains. Ingredients, packaging, and manufacturing equipment all play an important role in the environmental profile of a product. However, no company can source all of these materials in isolation. For a company to meet the eco-responsible standards demanded by consumers and required by regulations, it must be willing to innovate, improve transparency, and work with outside sources.

Open innovation (OI) is a well-recognized methodology that leverages technology assets both internal and external to the company to accelerate innovation. At its core, OI relies on transparency and collaboration. As such, there are many opportunities to exploit the synergies between OI and sustainability to improve environmental stewardship. Open innovation for sustainability (OIS) is driven by the reality of limited natural resources, public pressures, and high material costs to discover potential solutions for better waste and resource management. Companies successful in adopting OIS offer several best-practice techniques. Research also indicates that OIS implementation leads to a more complete application of traditional OI. For example, effective OIS companies are more likely to collaborate with competitors and nongovernmental organizations; embrace transparency and sustainability throughout their organization; and share beneficial intellectual property to enable future sourcing and supply-chain development across the industry.

Businesses in the cosmetic and personal care industries recognize that OI can benefit both R&D and the bottom line. Thus, as the industry becomes increasingly aware and committed to sustaining planetary resources, it is critical to highlight how OIS can spur innovation while also advancing sustainability and eco-responsibility. While the focus of this book is cosmetic and personal care industries, this chapter purposely includes examples from beyond this focus to emphasize that OIS is most effective when cross-fertilization and technology transfer from many industries provide the stimulus for generating the next leap in innovation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

12.1.1 Sustainability—a critical business issue

12.1.2 Innovation is a critical but challenging component of any

sustainability strategy1998

a. The concept of open innovation (OI)

b. Open innovation and sustainability are synergistic

c. Transparency

d. Collaboration

12.1.3 Integration of sustainability principles into innovation

practices is evolutionary

a. Six key traits of sustainable companies

b. Few companies explicitly recognize and exploit open

innovation as a tool to help them on this

sustainability pathway

c. Companies practice open innovation for sustainability

adopt a more complete model of open innovation

d. Practical lessons can be learned from companies that

have recognized the synergies between sustainability and OI

References

12.1.1 SUSTAINABILITY’A CRITICAL BUSINESS ISSUE

Numerous industries and everyday citizens are beginning to awaken to the realization that the world cannot continue on the same path of disregarding the environment and its limitations. The reality of limited natural resources, energy constraints, increasing pollution, tighter emerging environmental regulations, and green consumer demand have become new business drivers. These drivers not only threaten “business as usual,” but have the potential to impact life on this planet. The imperative nature of these demands is reshaping industries and supply chains as companies seek to compete effectively in this new emerging world.

In the face of these emerging drivers, eco-responsible companies and governments have a heightened awareness of the planet’s limitations regarding resources and have begun to adopt the principles of sustainability.

Sustainability as first defined by John Elkington (1998) is a focus on people, planet, and profit—a concept commonly referred to as the triple bottom line. Sustainability requires companies to measure their success not just by monetary increase, but also by the cost to the people that make the goods. Success is also measured by the impact on surrounding communities resulting from the creation of these goods and services, and the cost price paid by the environment. Once viewed as a fleeting consumer trend, sustainability is now seen as a new business paradigm (Nidumlo et al. 2009). In fact, a recent MIT Sloan Management report (Haaneas et al. 2011) recently found that companies believe sustainability will eventually become core to any business.

12.1.2 INNOVATION IS A CRITICAL BUT CHALLENGING

COMPONENT OF ANY SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY

Any organization attempting to produce goods and services that incorporate an awareness of planetary sustainability must inevitably innovate. In the first instance these innovations may be relatively “routine”—small adjustments for the company’s current mode of operation to adopt technologies or practices well proven in other similar organizations. Ultimately, however, more challenging innovations are likely to be required—innovations that require larger departures from current practice and involve greater risks. This is especially true of innovations that enhance a business’s sustainability, as they often require new or immature technologies that require varying degrees of development. For example, many waste-heat recovery, alternative-energy, and pollution-prevention technologies are not commercially viable, or the cost of these young technologies may impede their adoption.

It is often instinctive to automatically think of innovation for sustainability as primarily about technological innovation. It is certainly true that technical solutions are essential to mitigating many of a company’s negative environmental impacts—for example, technologies to increase water efficiency, to increase the recyclability of packaging, etc. Nevertheless, other types of innovation can also play a critical role in enhancing an organization’s sustainability practices—service innovation, business model innovation, financial innovation, etc.

A number of factors contribute to make innovation for sustainability particularly challenging:

- • Sustainability cannot be solved in a vacuum. Companies must consider the entire lifespan of a product to truly address sustainability. This includes components from sourcing, manufacturing, shipping, disposal of waste, consumer usage, and eventual disposal by the consumer. The complex nature of sustainability requires a company to consider parameters both internal and external to the company.

- • New technologies with the potential to improve sustainability are often at an early stage of development that can hinder adoption or move the cost of the technology beyond what a product can sell for.

- • Governments are actively involved in generating regulations that require more sustainable practices. While this invention is often beneficial (e.g., by ensuring a level playing field between competitors, by creating financial incentives that improve the business case for taking action), it also introduces an additional set of risks. When will government regulate? What will be the exact requirements of the regulations? Will government change the regulations? Will variations in regulations across states, countries, and geographical areas impact corporate practices, especially for multinational endeavors?

- • Greenwashing or overinflating a product or company’s “green” attributes has become a consumer concern. Thus companies fear being accused of greenwashing, and this can often prevent sustainable innovation.

a. The Concept of Open Innovation (OI)

The novel aspect of the vast majority of innovations is typically the new combination of some preexisting ideas, capabilities, and skills or resources—rather than the creation of some fundamentally new knowledge. Open innovation is based on the idea that the greater the variety of these factors brought together, the more innovations are likely to be generated. A critical component of open innovation is that a firm must be actively encouraged to open its doors to source innovations from outside the company. For many companies, this differs from prior approaches to product development, as custom and practice has until now required corporate secrecy about their innovations/inventions and they have therefore chosen to highly protect intellectual property or trade secrets from prospective competitors.

OI follows the premise that it is likely that someone has addressed a similar problem in another industry and can provide possible solutions to an innovation need. This alternative approach tends to mean “path dependency”: where firms have typically searched for new ideas in well-worn prior sources. An excellent example of this is that ingredient manufacturers for novel hair care materials frequently go to the carpet industry for their ideas since there is much common ground between these two types of products.

b. Open innovation and sustainability are synergistic

Many industries are beginning to realize that open innovation has the ability to enable sustainability goals and endeavors. Open innovation (OI) is particularly well situated for sustainability-focused innovation and is referred to as open innovation for sustainability (OIS). OI and sustainability inherently both require two important components: a high level of transparency, and collaboration.

As sustainability is really focused on people, planet, and profit, a large element of success for a sustainable company is gaining the people’s heart. Disingenuous attempts at sustainability and a track record of industry neglecting the environment in favor of the bottom line has created consumers that are skeptical when a company promotes its “green” attributes. Thus, credible green companies are now working to full disclosure, including disclosure of ingredients, packaging, and partners. These companies often invite outside groups to audit their sustainability practices and generate reports. This high level of transparency is critical to the success of any company pursuing green efforts.

In a similar manner, OI has the dual requirement of transparency. The act of seeking external partners and technologies naturally requires a greater degree of disclosure than a closed innovation approach. Many companies pursuing traditional innovation pathways work diligently to ensure that all innovation is kept secret and in-house. Companies active in OI often seek out intermediaries or post-innovation needs in public forums to help identify meritorious technologies. They additionally will externally leverage technologies that the company has developed with partners and other interested parties.

Companies unwilling to clearly define their innovation needs or negotiate openly will not gain the external partners they need to innovate and will not be successful at OI. These innovation activities necessitate that an OI company accept a greater degree of transparency into their development activities. Increased transparency is also being essentially forced on geographical areas by the regulatory actions of others. For example, in the cosmetic and personal care industry, European Union Regulations require documentation of toxicological properties that many small companies may not have. This results in an imperative for sharing of such data by larger companies with smaller ones so that full transparency is achieved.

The complexity of sustainability and the many parts that are required to truly follow a green path necessitate that a company must collaborate. No company can source all its ingredients, packaging, or manufacturing equipment eternally. Each of these components plays a significant role in the environmental profile of a product. For instance, a cosmetics company that uses all bio-based recycled packaging but uses ingredients including phthalates, carcinogens, or ingredients tested on animals would struggle to define their endeavors as green. However, for this company to meet the green needs demanded by consumers and required by regulations, they must be willing to partner and work outside with different raw material providers to address these issues. Sustainability requires these types of partner collaborations due to the complexity of the problem. Moreover, collaboration is inherent to OI. To seek outside one’s organization for external technology solutions cannot occur without some level of collaboration.

The dual needs of transparency and collaboration for both sustainability and OI mean that OI is an exceptionally well-situated innovation methodology to solve sustainability-focused needs. In fact, many sustainability companies have been found to follow OI approaches without a formal knowledge of OI or the intention to do so. These companies found that these approaches were just “right” for the technical challenge at hand. Furthermore, companies that have openly accepted an OIS approach and purposely use the methodology have seen greater gains related to their sustainability goals. OIS can be used to help to systematically increase a company’s green profile.

12.1.3 INTEGRATION OF SUSTAINABILITY PRINCIPLES INTO

INNOVATION PRACTICES IS EVOLUTIONARY

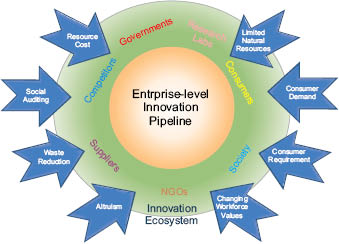

The process of incorporating sustainability principles into business practice is typically evolutionary. Figure 1.1 is a generalized model that illustrates the strategic drivers that push companies to become increasingly sustainable and the subsequent expansion of their innovation ecosystem by inclusion of a greater number of partners.

Figure 1.1: Sustainability drivers and the resultant expansion of the innovation ecosystem. Drivers are displayed as arrows and partner organizations are displayed within the ecosystem.

Companies often begin thinking about the sustainability of their products and practices, in the first instance, by relatively narrowly defined problems. Examples include government regulations (e.g., on emissions of air pollutants to the environment), consumer demand for a more sustainable product (e.g., recyclable packaging), and increasing cost of a resource (e.g., water) or a desire to decrease waste (e.g., raw materials). These early first steps are often accompanied by collaboration and inclusion within the innovation of partners such as their suppliers, government, and their consumers.

Once companies have started to make the transition to becoming more sustainable in some narrowly defined way, they are often exposed to new drivers to apply sustainability practices more broadly across their organization. Consumers, familiar with a few “green” products from a company, begin to expect that sustainability be fully embraced across the organization. These consumers may be unwilling to purchase products that do not meet the same levels of environmental stewardship. Thus consumer demand for a greener product may transition to a consumer requirement. This often also attracts the attention of a different workforce that is seeking to work with a company with principles. These employees once hired begin to change the company from the inside.

These increasing pressures internally from employees and externally from consumers push companies to quantify and publicly disclose their green efforts via approaches such as social auditing. Perhaps most importantly, accepting responsibility for environmental or social issues appears to change the way a company views itself. At this point society often becomes part of their innovation ecosystem. As Roger Cowe puts it:

Once a company has acknowledged it has to account for pollution . . . it is harder to deny wider social responsibilities. And once outsiders have been through the gates, it is impossible to stop them looking beyond one narrow aspect of business. Curiously, this odd little world of social auditing threatens to fuel a debate about the purpose and nature of 21st century capitalism which has escaped the politicians for decades.

Finally, companies can eventually reach a point at which the drivers they face are so strong or pervasive that they are pushed into completely embracing sustainability. One such driver at this stage is altruism. A company’s values, and mission, can evolve to the point that improving its own sustainability, and that of the world around it, is seen as being a core part of their reason for existence.

Another critical driver at this stage can be an emergent awareness of the physical scarcity of a resource—that is, an understanding that the company’s current pathway will ultimately lead to depletion of a critical resource to such an extent that the company’s very survival will be threatened. One such example can be found with Nike. Nike realized that the very nature of how they compete as a company will be impacted by constrained resources in the future. To that end they developed an Environmental Apparel Design Tool at a cost of $6 million to the company. The tool permitted Nike to assess the footprint, availability, and environmental characteristics of each technology incorporated into their products. Nike saw the value in this tool, but realized that its true value was diminished if it was limited to acceptance by one company as other companies may still be innovating in traditional, more resource-heavy methodologies. To that end, Nike shared this tool with industry.

Within the cosmetic and personal care community, destruction of natural resources (e.g., rare plants that are extracted for their essential oils) can often lead to a depletion of the critical resource, not to mention the devastating effect on the surrounding people, animals, and environment.

This understanding that corporate products and corporate survival are threatened by limited resources creates a superordinate goal, i.e., something that two parties normally in opposition to each other can agree to work together on as it is critical to their survival. This superordinate goal creates the greatest expansion of the innovation ecosystem as now companies begin to collaborate with their competitors on complex industry-wide innovation challenges and with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that industry has often had a combative relationship with.

a. Six key traits of sustainable companies

Through examining company behavior it has become clear that six traits are common among companies successfully using open innovation for achieving truly sustainable approaches:

- 1. Systemic: OIS companies are more likely to treat sustainability as a systems issue and understand that to be truly sustainable one must address the sustainability of the organization as a whole.

- 2. Enterprise-level: Within these organizations, sustainability is practiced at all levels, and all projects are evaluated for their environmental impact. This sets an expectation that sustainable solutions must be sought, whether from within the organization or from the outside.

- 3. Committed: These organizations are committed to sustainable practices for the long haul, understanding that future resource limitations will impact their industry and business model, and they are willing to take a “leadership” strategy. This contrasts with companies that practice sustainable innovation only in reaction to consumer demands (follower strategy) or industry regulation (compliance strategy).

- 4. Collaborative: OIS companies tend to have a greater number of partners in their innovation ecosystem than traditional OI companies. This is due to the fact that OIS often presents broader, more difficult, and more cutting-edge technology and sustainability needs that require expertise from multiple industries and partners.

- 5. Invested: These companies show a willingness to invest in building an entire supply chain that can provide more benign offerings at all levels, and they will choose to follow their principles as opposed to focusing on short-term gain. They also are more likely to truly adopt a triple bottom-line approach that measures the success of their company equally on people, planet, and profit.

- 6. Transparent: OIS companies embrace transparency via internal and external reporting, as well as in sharing their innovation needs with outside entities, and believe this is a competitive advantage.

Collaboration and transparency are essential elements of both improving sustainability practices and successful innovation (whether for sustainability outcomes or some other desirable result). Companies attempting to improve sustainability practices inevitably must collaborate in order to solve problems. A bread manufacturer must engage partners all along the supply chain if it is to reduce the carbon footprint of a loaf of bread. There is a strong body of evidence proving that companies trying to innovate in any sphere will be more successful if they collaborate with partners for ideas, to support development and to take new products to market. Transparency is a critical tool for building trusting relationships in both sustainability and innovation. This overlap creates the potential for powerful synergies that can help accelerate both innovation and sustainability practices. Some examples of the way in which these synergies can be exploited are outlined below.

Exploiting synergies between innovation and sustainability

- • In the process of become more sustainable, companies typically become more “open”—for example, they work with their suppliers, customers, and NGOs to understand sources of environmental or social impact along their supply chains. The relationships established in the process of opening up can then become an excellent community to work within an open innovation context. Companies can engage with this community to help generate new, innovative ideas and to collaborate during other parts of the innovation process. As another example, companies can work with suppliers on joint development of new technologies, or with NGOs to help test and validate whether new ideas will actually enhance sustainability.

- • Adopting open innovation practices will demonstrate to a company’s stakeholders that they are real about sustainability (since they’re being actively engaged in the process)—which helps to build trust and overcome potential perception of greenwash.

- • Adopting OIS helps companies recognize opportunities to work collaboratively with their competitors to address sustainability challenges which have a direct business impact. For example, making IP related to sustainability practices freely available can help reduce pressure on finite resources (which will likely have some impact on the resources’ price). It can also result in the industry as a whole being perceived by customers as a “sustainable” one—thus avoiding the possibility that one company with good sustainability practices is not tainted by a general perception of the industry as being unsustainable.

Few companies appear to actively link open innovation and sustainability initiatives. This appears to be due to a lack of awareness of the potential synergies, and to a relatively narrow understanding of the meaning of “open innovation” (e.g., assuming open innovation only means crowd sourcing).

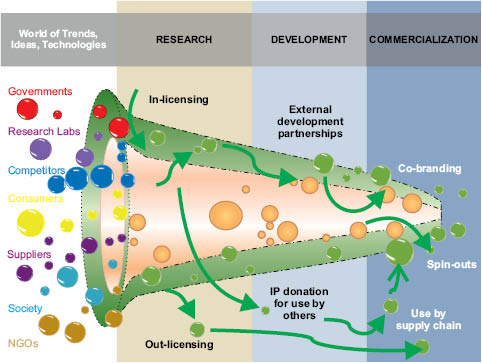

A number of common traits were identified during the course of our primary and secondary research into companies who are leveraging open innovation for sustainability outcomes. Additionally, it was found that the innovation ecosystem tends to expand as companies embrace OIS. This expansion of the innovation ecosystem alters the innovation process as shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: The new product development pipeline for companies practicing Open Innovation for Sustainability.

The most significant and unexpected finding of this study was that these companies appear to be using a more complete model of open innovation than companies that have adopted OI but not for sustainability outcomes. Most companies adopting open innovation for general innovation purposes are relatively selective about just how open they are (few partner with direct competitors), and also about the direction in which ideas travel (most see OI as a tool for harvesting ideas, and not for sharing internal ideas out).

Companies practicing OIS, by contrast, appear to be more likely to develop partnerships with stakeholders sometimes seen as hostile—e.g., direct competitors or NGOs. For example, recently there has been collaboration between furniture manufacturers to identify alternatives to halogenated flame retardants.

It also appears that companies practicing OIS are more likely to release technologies or ideas out into the world, as opposed to just treating open innovation as another source of new product ideas. In one approach, a number of companies have either donated intellectual property or licensed IP for a modest fee. Websites now exist for sharing green IP for the common benefit. Two such examples of IP sharing are the World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s Eco-Patent Commons and Nike’s GreenXChange.

The following practical lessons from companies who have sought to leverage the synergies between sustainability and open innovation can help to guide businesses interested in taking similar steps:

- • Understand that resource constraints will impact business. In many situations limited resources are here and if they are not here now, they will be in the near future. These limitations will alter the cost of raw materials and fundamentally change the way a company does business.

- • Embrace openness in your innovation challenges and sustainability goals. By partnering and working with numerous partners, organizations are more likely to develop robust products that address a greater number of sustainability challenges. This requires companies to take two important steps:

- – Strategically increase your innovation ecosystem.

- – Consider alternative points of view (e.g., NGOs and competitors).

- • Do not just take—you must also give. There is a tendency for companies using OI to focus on bringing external ideas in, but not sharing out internal ideas. The critical challenges facing the planet necessitate the sharing of ideas related to sustainability. Many companies are now realizing that they can create new models that allow the sharing of these ideas. Additionally, the sharing of sustainable technology helps to raise the ethical and green image of a company in the eyes of its consumers. Companies interested in sharing sustainable innovations should:

- – Consider out-licensing of sustainable technology and IP donation of green innovations that will benefit the industry.

- – Grow their supply chain with ideas built inside the company. This can help build a market related to these technologies that helps to mature these innovations.

- – Spin-out green technologies that they will not develop internally so that these green innovations benefit the industry at large.

- • Prepare now for a triple bottom-line approach. Many companies have already begun to follow the triple bottom line. However, a wider adoption of this approach is coming.

- • Do not focus innovation efforts solely on low-hanging fruit. For many industries, the focus has been on smaller, easier innovations that require limited technology investment. However, the paradigm by which companies operate is changing. This will require new bold technologies that address environmental challenges.

- • Treat OI as a methodology to facilitate collaboration. Collaboration is a key component to sustainability. OI is a methodology that can enable the collaboration needed to solve the grand challenges industry will face in the future.

Elkington, John. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business (1998)

Nidumolu R., C. K. Prahalad and M. R. Rangaswami (2009) Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation, Harvard Business Review, 87(9): 56-64.

Haaneas K, Arthur D, Balagopal B, Kong MT, Reeves M, Velken I, Hopkins MS, Kruschwitz N. (2011) Sustainability: The ‘embracers’ seize the advantage, MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter Research Report.

Roger Cowe, “Account-Ability,” The Planet on Sunday as published in WBCSD’s “Sustainable Innovation: Drivers and Barriers.”

PART 12.2

A BOTANIST’S VIEW OF SUSTAINABILITY:

USE OF ABUSE IN THE PERSONAL CARE INDUSTRY?

Author

Michael J. Balick

(Vice President of Botanical Sciences, Director of the Institute of Economic Botany, New York Botanical Gardens)

ABSTRACT

With increased public awareness of the finite nature of natural resources, there has been greater interest in living a sustainable lifestyle and reducing our footprint on the planet. In the personal care and supplements industries, the movement towards using more exotic and efficacious ingredients has led to concerns about their supply, particularly those that are wild harvested. As a result, sustainability has become not only a new supply goal but also a marketing mantra.

But what is sustainability from the biological perspective?

How do we assess the quantity of a raw material that can be harvested each year without destroying the population of the resource? The answer to these questions requires a biological and ecological evaluation of each raw material, whether it is harvested in the wild or cultivated. A basic model for establishing sustainability and harvest limits will be presented. Nature is a diverse but fragile source of important bioactive compounds, now and in the future, and must be protected as part of the process of commercialization and resource utilization.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

12.2.1 Introduction

12.2.2 What happens once you find a species of interest?

1. Accurate identification of botanicals

2. Understanding why the plant is used in the product,

and what part or form will give the best result to

the consumer

3. Truthful representation of the local uses of the plant in

marketing efforts

4. Making sure the environment is not degraded as a result

of harvesting botanicals

5. Ensuring that local communities are not negatively

impacted by the harvest of the plant

6. Under the spirit and intent of the United Nations–sponsored Convention on Biodiversity, compensation to groups and

source countries where the materials and ideas were obtained

12.2.3 Sustainable production of wild-harvested products

Acknowledgments

References

From earliest recorded history, humans have used a broad range of plants for adornment as well as other aspects of personal care. It is now estimated that there are over 300,000 species of flowering plants on earth. Currently botanists are identifying and describing approximately 2,000 new species of flowering plants each year. It has been estimated that 70,000+ species remain to be discovered and described. Today, only a relative handful of the plants once used traditionally for decorating and perfuming the body, soothing the skin and protecting it from the elements are utilized in commerce. Great opportunity exists for the “rediscovery” and use of plant-based ingredients in the personal care industry.

As a researcher who has spent much of his career studying ethnobotany and the relationship between plants and people in a traditional setting, with people who still live as their ancestors did many hundreds of years ago, with few links to the global economy, this author has frequently observed indigenous people using plants externally, for example as cosmetics or washes. Table 12.2.1 provides examples of the categories of traditional plant uses that may offer guidance for those seeking to discover and develop active ingredients and new categories for personal care products.

Table 12.2.1: Traditional Uses of Plants: Their Application in Personal Care

|

The process of identifying plant species that could provide raw materials of use for personal care and cosmetics involves a series of steps. These raw materials can be used as extracts, individual compounds, or their synthetic derivatives. First, one should have an excellent grasp of the literature on the species of interest or the type of activity (e.g., as anti-aging or sun protection) that is to be found in the plant world. This can help direct the search for species that can be screened for biological activity and also obviate the need for re-collection of species that have previously been investigated (unless of course there are new assays for testing).

The actual collection of plant samples can involve several strategies, including random surveys, phylogenetic surveys (Balick 1994), and ethnobotanically directed surveys (Cox and Balick 1994). The random survey has been likened to a shotgun approach, with large numbers of plants put through the available assays. Phylogeny, the study of the evolutionary relationships among organisms, can be employed if one is aware of a plant or compound with desired activity, and then searching its relatives in the plant kingdom to identify additional extracts or compounds that could potentially be of value.

The ethnobotanical approach involves learning the uses of plants by traditional peoples, evaluating their efficacy in an assay, and developing active extracts or molecules based on scientific evidence, as well as a documented history of use for a specific purpose. There are other approaches, but for our purposes these three ways of identifying plants for collection are a reasonable introduction to methods one should be familiar with to be effective in seeking out botanicals that can offer breakthroughs in new product performance and claims.

12.2.2 WHAT HAPPENS ONCE YOU FIND

A SPECIES OF INTEREST?

Once a species of interest is identified, the next question for use in the personal care industry is whether the material is available in sufficient quantities to meet market demands, and if so, is scale-up possible within a reasonable time period if demand increases dramatically. Plant-based resources, unlike synthetically produced compounds, take time to grow. Some species can be produced in farms, while others, such as tree crops requiring years to mature or produce, must to be wild harvested. One must also take into account that from year to year the crop may vary somewhat in view of environmental factors.

The purpose of this chapter is to examine some of the biological and ethical issues involved in using plant-derived ingredients. In particular we examine those issues that have been identified through an examination of their use by traditional cultures, as well as providing a brief summary of the concept of ecological sustainability. It is clear that this segment of the personal care industry is growing, and the author would maintain that with this growth come increasing responsibilities related to the environment and peoples from whom the raw materials and ideas are obtained.

We describe below a six-element approach for the development of personal care products based on the ethnobotanical approach that should be seriously considered by all companies and individuals committed, or considering becoming committed to this Herculean task.

- 1) Accurate identification of botanicals. It is important that all botanical ingredients in a product, whether in an herbal medication or cosmetic cream, be properly identified. Every product should be prepared using “good botanical practices” including properly collecting, identifying, and permanently documenting the plant-based ingredients. Specifics on the concept of “good botanical practices” can be found in Balick (1999).

- 2) Understanding why the plant is used in the product, and what part or form will give the best result to the consumer. In order to maximize the properties of plant materials used in any formulation, it is essential that each plant ingredient have a specific purpose and utility. Each plant ingredient should be present in its most effective form, as opposed to being added as a device to promote marketing efforts! Educated consumers have raised the bar in the Internet age and both need and demand products that work.

- 3) Truthful representation of the local uses of the plant in marketing efforts. The current application of commonly eaten food plants in shampoos promoted as traditionally used is an example of ethnobotanically based misrepresentation. These products sometimes imply they are based on traditional cultural use when, in fact, they are not. It would be beneficial to have an industry-wide agreement limiting claims of product ingredients having “centuries-old use” from around the world or by a specific culture, unless evidence can be shown through previously published or firsthand ethnobotanical studies that this is indeed the case.

- 4) Making sure the environment is not degraded as a result of harvesting botanicals. The “greening” of the personal care industry has led to an extensive demand for raw materials harvested from plants. Sometimes these plants are being harvested from wilderness areas without concern for the sustainability of the resources, ensuring that they thrive and can serve as a source of raw materials indefinitely. As a result of the growing demand for plant-based cosmetics, it is essential not to degrade the environment through overharvesting or unwise cultivation practices. The concept of a sustainable harvest will be discussed later in this chapter.

- 5) Ensuring that local communities are not negatively impacted by the harvest of the plant. As people harvest plant and other raw materials and ship them outside of their communities, a shortage of certain species that have traditionally been an important part of the local culture can arise. One example of this is the Brazil nut, now important in international commerce and primarily harvested from community lands. In creating markets for such products, industry needs to develop sources and production methods that will respect the people’s rights to access these essential and important plants, which they use for food, medicine, sacred rituals, and other purposes.

- 6) Under the spirit and intent of the United Nations–sponsored Convention on Biodiversity, compensation to groups and source countries where the materials and ideas were obtained. Sometimes, the formula for developing, manufacturing, and selling “natural” products—whether they be herbal medicines or personal care lines—is to utilize ideas from traditional knowledge that have been previously published, and to manufacture these goods using raw materials at the lowest price. The fairest way of doing business in this era, as expressed by the UN Convention on Biodiversity (http://www.cbd.int/), is to compensate people and their communities for the knowledge leading to their use in commercial formulations. This will enable them to benefit from the production of these products, often receiving financial remuneration from sales of the final products, as well as being involved in their cultivation, production, and processing.

12.2.3 SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTION OF

WILD-HARVESTED PRODUCTS1

Nowadays, the concept of sustainability is used in a rather cavalier fashion, with so many products—personal care and otherwise—being labeled as sustainably produced. In truth, we know very little about the sustainability of production for natural resources, including raw materials for the cosmetics industry, especially involving products wild-harvested from tropical ecosystems. Yet, it is these exotic products that are often touted as “unique” in an industry searching for the next important active ingredient.

When the organic foods industry was in its infancy, someone observed that several-fold times more organic produce was being sold than was actually being produced; the same can be said for “sustainably produced personal care products” from the rain forest, for example.

The ecologist Charles Peters of the New York Botanical Garden has undertaken many detailed studies of tropical forest trees in efforts to determine the level of sustainable production or harvest of each species (Peters 1996). According to Peters, “a sustainable system for exploiting non-timber forest resources is one in which fruits, nuts, latexes, and other products can be harvested indefinitely from a limited area of forest with negligible impact on the structure and dynamics of the plant populations being exploited.” A plant such as Brosimum alicastrum (Moraceae family), a tree found in Central and South America that is exploited for its protein-rich fruits, needs to produce over 1.5 million seeds to ensure that one tree will live long enough to reproduce. If most of the fruits produced by this species were to be harvested rather than left to grow in the forest, the population could become extinct over time. Similar portents of ecological disaster exist for many other botanical species.

Too little is known about the levels of sustainable harvest of many of the internationally important nontimber forest products (NTFPs), including the Brazil nut (Bertholettia excelsa). Some 200,000 people harvest the Brazil nut from the millions of hectares of Amazon forest where it grows, and they annually produce around 20,000 tons for the commercial trade. The harvest of this nut is one of the largest sources of cash income for many of the harvesters. In the early days of the Brazil nut “boom,” no one considered what would happen 50 or 100 years in the future, following the harvest and sale of the majority of seeds produced by once-great populations of Brazil nut trees.

Quite simply, the mature, seed-producing trees that are the backbone of the population would die and not be replaced by younger trees, and the resource base on which these industries are built would disappear. This has happened in many areas where this plant is native, as Peres et al. (2003) confirmed in a study of populations of Brazil nuts that had been exploited for many years. Local people and their governments, along with commercial traders and conservationists, now acknowledge that overharvest of this wild plant will lead to its devastation, and today there is greater sensitivity to the importance of ecologically sustainable harvesting protocols being used in gathering this resource.

What, then, are the options for the continued use of NTFPs as a tool for economic development and conservation of biodiversity in the future? Dr. Peters suggests a series of steps for exploiting NTFPs in a sustainable fashion. First, the species to be exploited should be carefully selected, after such factors as the ease of harvesting and resilience of natural populations to disturbance are considered. A tree valued for its roots will be harder to harvest than one valued for its fruits, and the harvest of a species that produces fruits in massive quantities at one time of year will be easier to manage than the harvest of a species that produces fruits sporadically throughout the year.

Once the species has been decided upon, a forest inventory should be undertaken to learn where the resource is found in greatest abundance and the number of productive plants per hectare. Investigators then should estimate the quantity of the resource produced by the species (yield studies) per unit of time, by conducting yield studies of different-sized individuals in different habitats. The next step is to define sustainable harvest levels, and harvest no more than the annual growth of the stem or leaves. The sustainable harvest level of a fruit is more difficult to determine, as discussed above, because a certain amount of seed (to be determined) is required to maintain population structure over time.

When these four steps have been taken, the harvesting of the resource can begin, but the careful measurement should continue. The status of the botanical population should be monitored for signs that the forest is being overharvested. People should examine the status of adult trees periodically to determine whether the flowers are being pollinated, whether large numbers of fruits are being consumed by predators, and so on. If problems arise, the harvest should be adjusted to keep its level below the rate that would threaten sustainability. If such fruits become so popular based on their use in personal care and cosmetic products, then the purposeful and careful management of the resource becomes essential to the long-term viability of the products.

When necessary, people may intercede to replant areas that do not seem to be regenerating, clean out competitive species, or open up the forest canopies to allow more light to reach the young trees and thus speed their regrowth. The precise measurements that Peters recommends can be somewhat expensive and time-consuming, and only a few species have been studied from this perspective. However, plant populations may be threatened if harvests are determined by the demands of the marketplace rather than the needs of the ecosystem. As Dr. Peters notes, “nature does not offer a free lunch.” In our enthusiasm to support conservation of the natural world by focusing on its usefulness to economies, we are perhaps inadvertently dooming elements of it to extinction. Peters’s book, Sustainable Harvest of Non-Timber Forest Products in Tropical Moist Forest: An Ecological Primer, is available for downloading at http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABT501.pdf.

An alternate, less technical, but useful analogy for of explaining the concept of sustainability is to think of a wild plant resource as a type of bank account that you require in order to survive, in a situation where you have no other source of income. This account consists of principal and pays some level of interest each year. Your time frame for needing to derive benefit from this bank account is forever, so you need to be careful not to spend the principal, and in fact with some production systems (e.g., fruits) it is important to leave some of the interest that accrues so that the principal does not fall victim to inflation over time. Therefore, with materials such as canes and leaves, you can spend all of the interest (yield) in a given year, while with other materials, such as fruits, you can only spend some of the interest during that time.2 In years of high interest this is a certain amount of money, but in years of low interest, this is a much smaller amount. Using this model, you will also need to subtract the inflation rate from the interest you are spending and add it back to the principal.

So it is with a natural population of plants that is producing a desired raw material. Use up the principal and pretty soon you have exhausted the resource. If you are harvesting fruits, then a percentage of the fruits must be left to regenerate new plants. If you are harvesting timber, then a percentage of the trees must remain to produce fruits that will develop into new trees, and so on. Determining the allowable harvest scenarios requires the process developed by Dr. Peters as described above.

Only when ecologically sound management plans based on scientific studies are developed for resource extraction will the use of those resources be able to contribute to the conservation of biological diversity as well as economic development and poverty alleviation of the population who are the owners or stewards of the particular botanical resource. It is only by following proper protocols that one can ensure ecological sustainability.

In addition to the ecological issues, there are a number of social issues that must be considered in the wild harvest or cultivation of plant species used commercially. A good example of this is the case history of marula (Sclerocarya birrea), a South African tree that is a source of food, timber, medicine, and oil used in the personal care industry. Details are discussed in Wynberg and Laird (2007). The authors describe issues including local laws and customs governing the use of this species, land and resource rights, and monitoring activities. They conclude that a combined approach to improving management that would involve both statutory laws and traditional customs would be most effective for this plant species. Each resource and context is different—all the more reason to look at the utilization and exploitation of a species individually, developing protocols that are economically and ecologically effective on a case-by-case basis.

There is great potential for use of some of the little-known plants found in remote corners of the earth in the personal care industry, but this potential can only be realized if a new and equitable framework for the discovery, harvest, and trade of these raw materials is developed. We encourage product developers and marketers alike to use the material presented herein as an essential part of product development for the personal care and cosmetics industry. Look deeper than the products’ performance lest there be a great commercial success but no raw material to allow for the growth of profits.

My thanks to Dr. Charles M. Peters for his careful explanation of the principles of ecological sustainability discussed in this chapter, as well as to Meyer Rosen for his insightful editing of an earlier version this manuscript.

M.J. Balick, 1994. Ethnobotany, drug development and biodiversity conservation—exploring the linkages. Pp. 18-24. In: Ethnobotany and the Search for New Drugs, Ciba Foundation Symposium 185. Chadwick, Derek J. and Joan Marsh (eds.) Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

M.J. Balick, 1999. Good botanical practices. In: D. Eskinazi, M. Blumenthal, N. Farnsworth, and C. Riggins. (eds.). Botanical Medicine: Efficacy, Quality Assurance, and Regulation, pp. 121-125. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, NY.

P. A. Cox and M. J. Balick, 1994. The ethnobotanical approach to drug discovery. Scientific American 270(6)82-87.

C. A. Peres, et al., 2003. Demographic Threats to the Sustainability of Brazil Nut Exploitation, Science 19 December. Vol. 302 no. 5653, pp. 2112-2114.

C.M. Peters, 1996. Observations on the sustainable exploitation of non-timber tropical forest products: An ecologist’s perspective, pp. 19-39 in M. Ruiz-Perez and J.E.M. Arnold (eds.) Current Issues in Non-Timber Forest Products Research. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Bogor.

C. Peters, 2001. Lessons from the plant kingdom for conservation of exploited species, pp. 242-256, in J. Reynolds, G. Mace, K. Redford and J. Robinson (eds.). Conservation of Exploited Species, Cambridge University Press.

R.P. Wynberg and S.A. Laird, 2007. Less is often more: Governance of a non-timber forest product, marula (Sclerocarya birrea subsp. caffra) in southern Africa. International Forestry Review Vol 9(1) 475-490.

1. This section was originally published in M.J. Balick and P.A. Cox. 1996. Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany. W.H. Freeman, Scientific American Library, and updated for use in this paper.

2. Peters (2001) divides plant products into three categories: vegetative tissues (e.g., bark), reproductive propagules (e.g., fruit), and plant exudates (e.g., latex).

PART 12.3

THE HERBORETUM NETWORK FOR PROMOTING

LOCAL CULTURES AND BIODIVERSITY

Author

Geneviève Bridenne (CIO, Alban Muller Group)

ABSTRACT

Biodiversity, living womb of the planet, is a pool for a variety of products and molecules of great interest to the cosmetic companies and a source of new plant ingredients. Preserving biodiversity is a life insurance for humankind and future generations, but also for cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries that explore and use the big natural reservoir of the planet.

To preserve and enhance biodiversity with a scientific, economic, educational, and cultural way, nature enthusiasts concerned with its preservation (scientists, botanists, lawyers, industrial players, etc.) came together in 2004 to create the Association of the Herboretum, and to make this “herbs’ paradise” an open-air laboratory dedicated to plants for beauty, health, and well-being.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree