The normal mature non-lactating female breast weighs 200 g on average (range 30 g to greater than 500 g), whereas the lactating breast may weigh more than 500 g. The average adult breast measures 12 cm in diameter and 6 cm in thickness. The right breast is usually less voluminous than the left one, with an average volume of 275 mL for the right breast versus an average volume of 290 mL for the left breast. This phenomenon has been linked to the handedness. No correlation was demonstrated between breast mass and risk of cancer, because large breasts do not necessarily contain more abundant glandular tissue.

The female breast is placed on the chest wall, over the pectoralis muscle with the vertical axis extending from the second to the sixth rib and the horizontal axis extending froma the sternal edge to the midaxilla. However, the peripheral anatomic boundaries of the breast are quite arbitrary, other than at the deep surface, where the gland overlies the pectoralis fascia. The breast glandular tissue extends from the upper-outer quadrant into the axilla, as the tail of Spence. Superficially, the breast extends over portions of the serratus anterior muscle laterally, inferiorly over the external oblique muscle and superior rectus sheath, and medially to the sternum.

Anatomically, the breast lies in a space enveloped by fascial tissues, respectively the superficial pectoral fascia anteriorly, and the deep pectoral fascia posteriorly. These two layers are connected by fibrocollagenous element, forming the so-called suspensory ligaments of Cooper. Microscopic extensions of gland attach the skin and nipple to the breast. Cooper’s ligaments are more numerous in the upper part of the breast. Sometimes cutaneous manifestations of parenchymal mammary lesions, such as skin dimpling and nipple retraction, may be due to involvement of suspensory ligaments, causing their distortion or contraction.

The deep membranous layer of pectoral fascia is separated from the fascia of the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles by a space filled with loose connective tissue, which allows the breast some degree of movement over the underlying muscle fascia. Fibrous extensions of the superficial fascia traverse this retromammary space, forming the so-called posterior suspensory ligaments. Microscopic extensions of glandular breast tissue may be found in the posterior suspensory ligaments, in the retromammary space, and, rarely, in the fascia of underlying pectoral muscle. Such extensions of breast glandular tissue are a normal anatomic findings but have clinical implications. Actually, current mastectomies are successful in removing not more than 90 % of breast glandular tissue (Fig. 2.2).

The axillary fascia, at the dome of the pyramidal axillary space, is formed by an extension of the pectoralis major muscle. A fascial layer arising from the lower border of the pectoralis minor joins an extension of the pectoralis major fascia, forming the suspensory ligament of the axilla in continuity with the fascia of latissimus dorsi muscle. An inconstant muscle band in this fascial plane is referred to as the suspensory muscle of the axilla. The fascial boundaries of the axilla represent important landmarks for the dissection of the axillary content (Fig. 2.3).

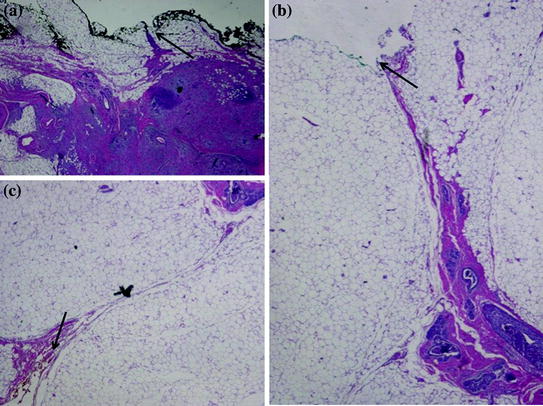

Fig. 2.3

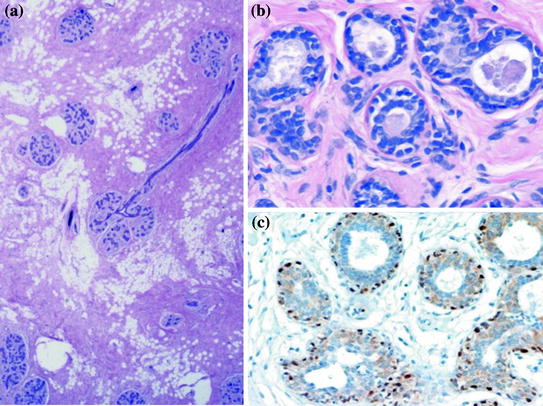

a The terminal ductal lobular unit (TDLU) consisting of a lobule and its paired terminal duct, represents the functional unit of mammary gland (HE 200x). b The lobular alveoli and terminal ducts are lined low-columnar to cuboidal epithelium, which is supported on its basal surface by a distinct layer of myoepithelial cells (HE 400x). c Myoepithelial cells are stained by antibody directed against p. 63 (SABC method 400x)

The nipple is centrally located on the skin of the breast, typically overlying the fourth intercostal space in younger women, although its level in the thorax may be widely variable. Normally, the nipple appears as elevated from the surrounding areola, both of them being more pigmented than the remaining breast skin. The pigmentation of the nipple and areola varies also with the woman’s parity. These structures are less pigmented in the nulliparous and become more pigmented from the second month of pregnancy. This tinctorial change after pregnancy is irreversible (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4

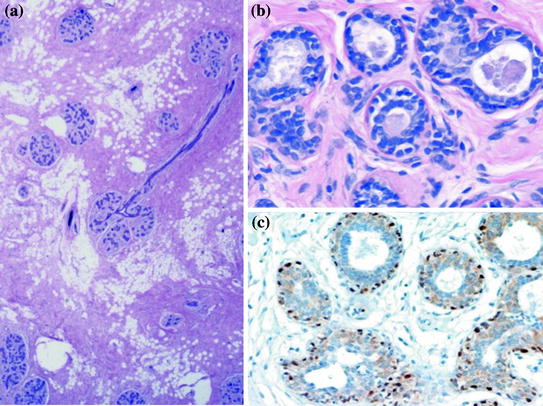

The use of several different color dyes allows to distinguish on the histological slides the different surgical margins. In this case the deep margin was marked with black ink (A, HE 20x), the anterior margin was marked with yellow ink (B, HE 20x), and the medial margin was marked with green ink (C, HE 20x)

The skin of the nipple contains sebaceous glands. In the areolar region, the so-called glands of Montgomery are found. They are large modified sebaceous glands which ducts opening on the surface of the areola into the tubercles of Morgagni. The glands of Montgomery enlarge during pregnancy and contribute to a milk-like secretion that moistens the nipple and areola skin. Unlike sebaceous glands, they undergo atrophy after menopause.

2.2 Functional Anatomy

The mature adult breast is composed of between 15 and 25 grossly defined lobes, each emptying into a separate major duct, terminating in the nipple. These anatomic subdivisions may be appreciated after injection of the duct system with visible or radiopaque dye. The lobes are arranged around in the breast in a radial manner. Three dimension reconstruction of the duct system of the breast demonstrated that each duct drained an independent territory. Each lobe appears as a cone with its apex at the nipple and its base in the region of the deep fascia, where most lobules are found. As the lobes grow intricately into one another around their edges, they do not appear as grossly identifiable entities. Thus, the extent of each lobe is not appreciable on gross inspection at operation or on dissection of the resected breast or in histologic sections. The anatomic extent of each lobe duct system is higly variable. Some of them may extend beyond a quadrant, but the smaller ones may occupy much less than a quadrant. Most authors consider lobes as independent systems; however, it may not be excluded that a few lobes may interconnect via ducts at some level, although a clear-cut evidence for this is lacking. According to this anatomic model, intraductal carcinoma extends in the long axis of the lobe along the duct system. Interlobar anastomosis, they do exist, cold potentially allow intraductal carcinoma to spread beyond the primarily affected lobar system. The duct lobar functional architecture provides an anatomical rational for treating some benign conditions by major duct excision and some malignancies by quadrantectomy.

The nipple contains the orifices of collecting ducts, which may be as few as 8 and as many as 24 (20 on average), and are generally arranged in a central group and in a peripheral one. The openings of the collecting ducts contain epithelial debris within their lumen in the non-lactating breasts, whereas during pregnancy they function as milk repositories. The lactiferous ducts in the nipple are surrounded by circular and longitudinal bundles of smooth muscle. The contraction of these muscle results in local venus stasis, nipple erection, and emptying of the milk sinuses. The portion of the duct system immediately below the collecting duct is the lactiferous sinus, in which milk accumulates during lactation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree