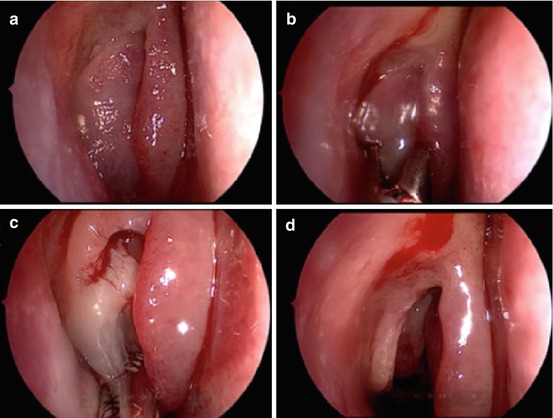

Fig. 28.1

Left nasal cavity showing polyp filling the middle meatus. In this revision case, residual uncinate is seen lateral to the polyp and must be addressed

Fig. 28.2

Progression of surgery for polyps. (a) Polyps in the middle meatus. (b) Representative piece taken for histology. (c) Microdebrider usage. (d) Exposed uncinate and bulla ethmoidalis. The remainder of the surgery is carried out in the same manner as non-polyp patients

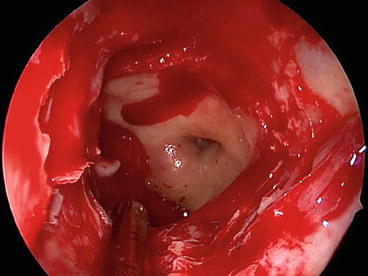

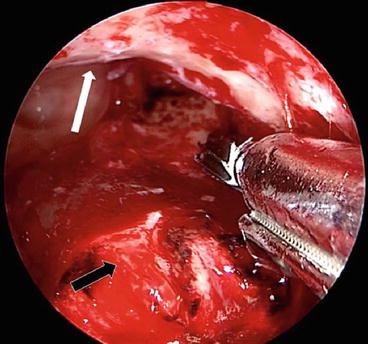

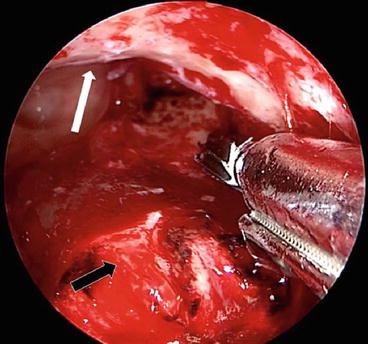

Fig. 28.3

Wide left sphenoidotomy showing the optico-carotid recess posterolaterally, skull base superiorly, and orbit laterally

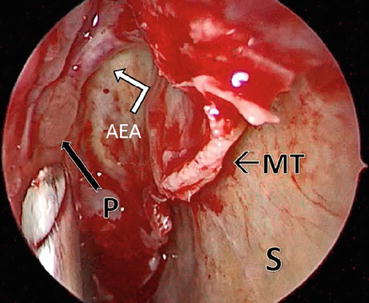

Fig. 28.4

Revision ESS for polyps requiring an aggressive approach. Picture shows the suction curette approaching the polypoid tissue (P) near the anterior ethmoidal artery (AEA) that lies on a mesentery along the skull base. This case required a frontal drill-out as well as trimming of the middle turbinate (MT). The septum (S) is marked for reference

In patients who have not previously undergone surgery, the easiest way to understand the anatomy of the frontal drainage pathway is to perform a careful analysis of the CT scans, identify each individual cell, and place them in their anatomical location so that a 3D conceptualization of the anatomy is achieved [18]. In general, cells that lie anterior to the drainage pathway are considered frontal ethmoidal cells, starting with the most anterior ethmoid air cell, the agger nasi. Cells posterior to the drainage pathway are typically suprabullar cells, and if they extend into the frontal sinus, they are denoted as frontal bullar cells.

Upon passing the axilla of the middle turbinate, the most commonly encountered drainage pathway is located posterior and medial to the agger nasi/frontal ethmoid cells. However, certain predisposing factors may cause the drainage pathway to run anterior or lateral such as an intersinus septal cell. In the case of polyps, the bony divisions on the preoperative CT scan can be difficult to discern and must be looked at with caution.

Indications

Indications to proceed with surgery for nasal polyposis are largely dependent on patient symptoms, the two most common symptoms being nasal airway obstruction and loss of the sense of smell. Other symptoms may include allergic symptoms (sneezing, ocular/nasal pruritus, rhinorrhea, etc.), recurrent bouts of sinusitis (colored nasal discharge, fevers, facial pain, etc.), or even a change in voice due to decreased resonance in the nasal airway. It is important to discuss the chronic nature of the disease with the patient. Although many of the symptoms that affect the patient may be improved by surgery, patients need to know the limitations of surgery. For example, nasal allergic symptoms and reactions to environmental triggers usually require ongoing medical management after surgery.

Although symptoms of polyp disease are often quite specific, there are some important exceptions to consider when working up a patient with polyps. Any patient with unilateral polyp disease should be biopsied to rule out papilloma, other benign tumors, or malignancy. Any suspicious lesion on endoscopy, a lesion that has a tendency to bleed, a polyp that does not respond to steroids, any expansile lesion seen clinically or radiographically, and especially any nasal mass that appears erosive or invasive also warrant a biopsy. If the clinical picture suggests a highly vascular tumor or an encephalocele, in-office biopsies are avoided and further workup is performed.

Once a patient is diagnosed with nasal polyps, a trial of maximal medical therapy is typically warranted prior to considering surgery. However, it has been increasingly recognized that patients with massive nasal polyps will have only short-term temporary relief [22], and the risks and benefits of offering a course of systemic steroids versus going straight to surgery need to be discussed with the patient. Initial treatment of polyps is often successful in reducing patient symptoms, but the frustration lies in the tendency for polyps to recur. Although systemic steroids are effective in reducing the size of polyps and improving symptoms, these medications have significant side effects, especially with long-term use. Recent research has looked at the risk-benefit of repeated steroid usage and found that the risks of steroid use start to outweigh the benefits once the steroids are used more than twice a year [23]. The most essential consideration in all patients is the importance of discussing the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the surgery so that expectations are fully anticipated and aligned with realistic goals.

Preoperative CT scans where surgery for nasal polyposis is to be performed are essential. However, the universal use of image guidance during polyp surgery is not an absolute and generally varies according to surgeon preference and image-guidance availability. Patients whose biopsy results show anything other than typical inflammatory polyposis will generally require an MRI and further workup prior to surgery, and their treatment will vary depending on the diagnosis.

Surgical Technique

For many centuries, nasal polyps have been written about, and records reflect the various attempts that have been made to eradicate them [24]. In the 1970s Messerklinger introduced the concept of nasal endoscopy [25, 26] followed by Stammberger’s adaptation in the 1980s, popularizing a more functional approach to the sinuses [27–29]. Stammberger’s technique is based on limited tissue resection with the aim of reestablishing the natural drainage pathways of the sinuses. It has been shown to be effective in CRS patients but appears to be less effective in patients with a high disease load. In this patient group, usually defined as a Lund and MacKay score of more than 12 out of 24, a more radical approach has been shown to be more effective in reducing polyp recurrence. Inflammatory disease load is comprised of polyps and surrounding mucus. It is often thick, tenacious, and difficult to clear from the sinuses. The polyps have activated eosinophils that, if remain after surgery, quickly reactivate the inflammatory cascade and result in disease recurrence. The mucus, in turn, has bacteria often in the form of biofilms and may have superantigen producing Staphylococcus aureus. In subgroups of polyp patients, fungal elements promote inflammatory stimulation of the mucosa. These patients exhibit a high incidence of disease recurrence should the fungal mucus not be removed at the time of surgery.

Upon commencing surgery, the initial step is to take a representative polyp from each side and send this for histology. The microdebrider is then used to remove the intranasal polyps and delineate the middle turbinate and the uncinate process. Due to tendency of nasal polyps to compress nearby structures, the uncinate process is carefully assessed as it may be paper-thin and plastered against the orbit or it may be retroflexed upon itself (Fig. 28.5). A sickle knife is used to cut the upper region of the uncinate while a backbiter frees the inferior portion and a “swing-door” technique is used to finish the uncinectomy (a ball probe is used to fracture the uncinate forward; then a 45° through-biting forceps is used to remove the mobilized uncinate flush with its insertion on the frontal process of the maxilla).

Fig. 28.5

Caution must be taken in polyp cases as the anatomy may initially be distorted. In this right nasal cavity, the uncinate process is retroflexed as well as polypoid

Once an uncinectomy has been preformed, a 30° scope with a curved suction and right-angled ball probe is used to identify the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus. The ostium is enlarged into the posterior fontanelle and a 70° scope is used to assess the sinus for disease. In the author’s hands, a fully diseased maxillary sinus with polyps throughout the sinus is best approached with a canine fossa trephination rather than a mega antrostomy in order to reach the anterior medial and lateral walls of the sinus. This allows for an efficient and thorough clearance of the maxillary sinus with effective, long-standing postoperative results [30]. The incidence of lip and teeth numbness if the correct landmarks are used for this procedure is around 3 % after 6 months. The landmark for canine fossa trephine is the mid-pupillary line and the floor of the nose.

The approach to the frontal sinus varies from surgeon to surgeon. In a previously unoperated patient, utilizing the axillary flap through the front face of the agger nasi cell allows a direct approach with good visualization while still predominately using the zero degree endoscope. Once the agger nasi and frontal ethmoidal cells have been removed, the pathway to the frontal sinus is cleared using a combination of angled instruments (giraffes, frontal punches, angled microdebriders, etc.) and angled scopes. All polyps are removed, the mucosa is trimmed but not stripped, and all partitions of the frontal recess are removed to ensure the maximal aperture of the frontal sinus.

Next the bulla ethmoidalis is opened and polyps are removed. The orbital wall is delineated with all partitions and polypoid mucosa trimmed down until flush with the lamina papyracea. Again, frequent palpation of the globe and careful attention is paid to the fact that the already thin lamina may be dehiscent in the case of polyps. The middle turbinate basal lamella is then opened medially at the junction of the horizontal and vertical portions of the lamella. An additional landmark is the level of the maxillary roof. The posterior ethmoids are visualized along with the superior turbinate, which will be in a medial and superior position. The inferior third of the superior turbinate is removed, thus exposing the sphenoid sinus natural ostium. Often polyps will need to be removed from the posterior nasal cavity inferior to the superior turbinate and even medial to the middle turbinate. Caution is taken to avoid the cribriform plate any time while working medially and superior in the nose. Next the sphenoid sinus is opened widely from the skull base to the level of the posterior septal artery. If the artery is transected, then suction cautery is used to achieve hemostasis. Polyps are removed from within the sphenoid sinus; powered instrumentation use is avoided within the sphenoid sinus near the optic nerve or internal carotid artery.

Traversing along the skull base from the sphenoid sinus toward the frontal sinus, the final partitions of the ethmoidal complex are removed, leaving mucosa on the roof while ensuring that all cells are open and the polyps are trimmed down to within approximately 1–2 mm of the bone. Caution is taken to identify and avoid the anterior ethmoidal artery should it be on a mesentery (Fig. 28.4) and therefore at risk for transection. The frontal recess and frontal ostium are again checked and cleared of any remaining polypoid tissue with maximization of the frontal ostium.

In patients in whom polyps recur, this is usually first seen in the frontal ostium/recess before the polyps and then spreads to the ethmoids. Why the recurrences start in this region and whether the narrow frontal ostial region predisposes to polyp formation are still unclear. In patients who have had a complete ESS with clearance of all polyps and ostia and who develop a recurrence, a modified Lothrop/Draf III or frontal drill-out may be required. This starts with complete clearance of all the other sinuses and a trimming of the lower half of the middle turbinate. This creates a much improved ventilation and topical therapy access to the posterior ethmoids and sphenoid region. Next the frontal drill-out is done. This creates a large common frontal ostium and allows effective topical application of steroids in the postoperative period. It improves the ventilation to the frontal region and, in a survey of outcomes from our department [2], has proved to be highly effective in reducing the incidence of polyp recurrence postoperatively. The frontal drill-out starts with a septal window with the posterior margin of the window formed by the anterior ends of the middle turbinates. The lower border of the window should allow an instrument to be passed from one side of the nose across the septum and under the axilla of the middle turbinate on the opposite side. The anterior margin is taken anteriorly until the frontal process of the maxilla anterior to the uncinate can be seen with an endoscope passed through the septal window via the opposite nostril. The upper rim of the window is taken onto the roof of the nose. Next, the frontal sinus mini-trephines are placed and fluorescein-stained saline is injected into the frontal sinuses so that the fluorescein can be seen draining through the natural frontal sinus ostium. This gives the surgeon the posterior landmark for the surgery. The drill is always kept anterior to the fluorescein. Drilling starts on the frontal process of the maxilla and progresses laterally until the skin is exposed giving the surgeon the lateral landmark. Drilling proceeds superiorly (not medially) until the floor of the frontal sinus is opened. This is done bilaterally; then the first olfactory neuron is identified determining the anterior projection of the skull base. This is confirmed with image guidance. The intersinus septum is taken down and the frontal “T” drilled back onto the skull base. An angled bur is used to take the superior edge of the neo-ostium away until the anterior wall of the frontal sinus runs smoothly out into the nose (Fig. 28.6).

Fig. 28.6

Frontal drill-out being performed utilizing a high-speed 3 mm angled bur to ensure the frontal sinus drains smoothly into the nose (white arrow). The maximum anterior-posterior (AP) diameter is achieved by drilling the frontal “T” (black arrow) down to the anterior projection of the cribriform plate

In a study looking specifically at the recurrence rate of polyps after frontal sinus drill-out (Draf III) procedure compared to standard ESS with a Draf IIa frontal sinusotomy, the Draf III patients required significantly less revision surgeries [2]. This was even more evident in asthma and aspirin-intolerant patients. The overall revision rate was 18 % (follow-up duration >12 months, median = 29 months), with a 37 % revision rate in the ESS group versus 7 % in the Draf III group (P < .001). Survival analysis showed that the Draf III significantly reduced the risk of revision (hazard ratio = 0.258, P = .0026). We postulate that the more aggressive surgical approach to nasal polyps tends to maximize ostia size, clear the sinuses of the inflammatory load, and allow postoperative topical medications to reach all aspects of the sinuses and therefore reduce the incidence of polyp recurrence.

Complications

Before discussing iatrogenic complications of surgery for polyp disease, a brief overview of the possible complications that can arise from the polyps themselves is warranted and should also be discussed with patients. Left untreated, polyps have a wide range of natural growth patterns. In rare cases, polyps may resolve spontaneously. In other cases, polyps might grow to a certain size and remain stable; symptoms such as nasal blockage, rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, and hyposmia/anosmia may persist. However, in cases of more aggressive polyposis, more serious complications may arise. Firstly, polyps may grow large enough to block sinus outflow pathways and promote bacterial and fungal growth, thus leading to infectious sinusitis. Obstruction of sinus ostia may lead to mucocele formation with subsequent erosion of the orbit and/or skull base. Secondly, polyps may enlarge enough to cause complete bilateral nasal airway obstruction and even protrude from the nostrils. Lastly, benign nasal polyposis may also exhibit an aggressive growth pattern causing orbital violation or penetration into the skull base.

Alternatives to surgery should be discussed with patients as well. The most efficacious oral medications for treating nasal polyps, corticosteroids [31, 32], are fraught with side effects and occasionally cause permanent sequelae [33, 34]. Probably the most worrisome complication with enduring ramifications from corticosteroid usage is avascular necrosis of the hip joint. Although this has a known risk of 9–40 % when long-term therapy is needed, avascular necrosis is limited to case reports when used in 0.5 mg/kg doses for short-term treatment (less than 3 weeks) and is primarily found after intravenous usage [35–37]. In fact, in a survey by Madanagopal et al. of over 600 orthopedic physicians prescribing oral steroids, no cases of avascular necrosis were reported over a 2-year period [38]. Regardless, a brief discussion of the risks of steroids, antibiotics, or other medications used for treating nasal polyp patients should be included during the office visit. Considering the tendency for polyps to recur, a multimodality treatment approach is often necessary, and reviewing the risks and benefits of each therapy becomes essential (Table 28.1).

Table 28.1

Risks of surgery, corticosteroids, or no intervention for nasal polyps

Surgery | Corticosteroids | No intervention |

|---|---|---|

Visual impairment Blindness Vascular injury Death CSF leak Meningitis Anosmia Epiphora Need for further surgery Synechiae Return of polyps | Psychosis Insomnia Mood swings Nightmares Reflux/gastric ulcers Weight gain Moon facies/buffalo hump Avascular hip necrosis Increased blood sugars Immunosuppression Cataract development Temporary relief only | Continued nasal obstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|