■ Glucose intolerance is often mild and insulin administration usually is not required.

■ Weight loss is often out of proportion to the amount of tumor burden and is due to the catabolic effect of excess glucagon.

■ Stomatitis, glossitis, and diarrhea are other frequent findings.

■ Psychiatric manifestations may include depression, anxiety, and psychoses.

■ Glucagonoma creates a hypercoagulable state, and 30% of patients will experience a thromboembolic event.5

■ A thorough personal and family history should be taken, with particular interest in other endocrinopathies because glucagonomas may be associated with MEN-1. Glucagonomas may also secrete secondary hormones, which may lead to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in up to 10% of patients. Less commonly, they may secrete vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), pancreatic polypeptide, somatostatin, or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).6

DIAGNOSIS

■ Diagnosis is confirmed by high levels of fasting serum glucagon (>1,000 pg/mL; normal, <150 pg/mL). Other conditions that cause hyperglucagonemia include hepatic insufficiency, stress, sepsis, and starvation, but levels rarely reach beyond 500 pg/mL.

IMAGING

■ Glucagonomas are typically greater than 5 cm at time of diagnosis and are easier to localize preoperatively than most PNETs. Most glucagonomas are located in the body or tail of the pancreas. Rarely, they may be located outside the pancreas in the duodenal wall, accessory pancreatic tissue, or the kidney.

■ Triple-phase computed tomography (CT) scan is the first-line localization study. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) can also be used and can identify extraabdominal spread to lymph nodes and liver.

■ Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), visceral angiography, and portal venous sampling may be required for glucagonomas that are difficult to identify, but this is very unusual.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ The goal of operative management of glucagonoma is an R0 resection including the primary tumor and all metastases. Patients who cannot undergo R0 resection benefit from tumor debulking because it can palliate symptoms due to excess glucagon by decreasing the levels of circulating hormone.

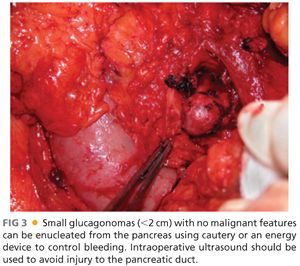

■ If the tumor is limited to the pancreas, surgical resection can completely reverse all clinical manifestations of a glucagonoma. This demands a formal pancreatic resection due to the large size of the tumors, usually a distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is required for tumors in the head of the gland. Resection should include peripancreatic lymph node dissection. Although smaller tumors may be technically amenable to enucleation, the high malignant potential of these tumors suggests caution with this approach (FIG 3).

■ All nodal and hepatic metastases that can be safely removed should be excised. Hepatic metastases may be managed by either wedge resection or formal hepatic resection.

■ Tumor debulking leads to a dramatic improvement in symptoms and the hormonal manifestations of glucagonoma may be diminished for years. Repeat debulking of recurrent disease may also prolong survival.

■ In patients with MEN-1, consideration must be given to the presence of other functional and nonfunctional PNETs. If hyperparathyroidism is present as a component of the MEN-1 syndrome, it should be treated before addressing the pancreatic tumor to avoid problems with postoperative hypercalcemia.

Preoperative Planning

■ Preoperative management is focused on treating the metabolic effects of excess glucagon and preventing or treating venous thromboembolism.

■ Somatostatin analogue therapy with octreotide is titrated to symptomatic improvement. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be needed if marked cachexia is present and may also help ameliorate necrolytic migratory erythema.

■ Hyperglycemia and diabetes, when present, should be controlled.

■ Patients should receive anticoagulation with Coumadin or low-molecular-weight heparin at the time of diagnosis. Preoperative placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter may be necessary in patients with a history of thrombosis.

TECHNIQUES

POSITIONING

■ As most patients present with metastatic disease and may require both pancreatic and hepatic resection, an open approach is preferred. For tumors confined to the pancreas, a laparoscopic approach may be possible. The open approach will be first described here.

■ The patient is placed supine with arms either extended laterally or tucked according to surgeon preference.

INCISION

■ Midline laparotomy, extended left subcostal, chevron, or a combination of these are all acceptable approaches to the abdomen and should be chosen based on surgeon preference and experience, the body habitus of the patient, and the possible need for hepatic or other organ resection.

DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY WITHOUT SPLENECTOMY

■ After the abdomen has been explored, the lesser sac is entered by separating the greater omentum from the transverse colon. The short gastric vessels must be preserved to provide blood flow to the spleen.

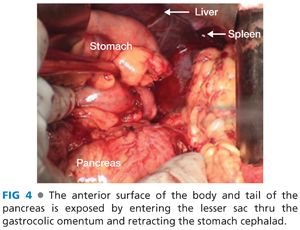

■ Mobilize the posterior wall of the stomach off the anterior surface of the pancreas and retract the stomach cephalad. The stomach may be held in place with retractors or stay sutures. The anterior body and tail of the pancreas should now be fully exposed (FIG 4).

■ Incise the peritoneum along the inferior border of the pancreas along the length of the body and tail. Gently elevate the pancreas off the retroperitoneum using blunt dissection along the avascular plane.

■ The splenic artery and vein, which run along the superior border of the pancreas (the vein runs posterior to the artery), will be elevated along with the rest of the pancreas.

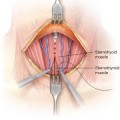

■ Determine the point of transection for the pancreas. This should be just to the left of the superior mesenteric vein in the pancreatic neck.

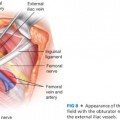

■ Bluntly develop a plane between the splenic vessels and the pancreas at the point of transection. Place vessel loops around the splenic vessels to facilitate retraction and provide vascular control (FIG 5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree