Fig. 26.1

Endoscopic view of anterior ethmoid artery (asterisk) at the left ethmoid roof. Patent frontal sinus ostium noted just anterior to the artery

The frontal recess opens into the ethmoid infundibulum inferiorly. The uncinate process can represent the medial or lateral boundary of the frontal recess depending on its development and position. Most often, the anterior superior portion of the uncinate is fused to the lamina papyracea and the ethmoid infundibulum is closed superiorly, forming a blind pouch called the recess terminalis. As a result, the frontal recess communicates with the middle meatus or suprabullar recess. Alternately, the uncinate can extend directly superior to the skull base or fuse with the middle turbinate. In these latter two configurations, the uncinate process forms the medial wall of the frontal recess as it drains directly into the ethmoid infundibulum.

The exact configuration of the frontal recess can be quite variable and is dependent on the three-dimensional pneumatization pattern of the ethmoidal cells in the frontal recess. Various cells can potentially populate the frontal recess, including the agger nasi, supraorbital, frontal, frontal bullar, suprabullar, and intersinus septal cells. The rate of pneumatization of the agger nasi region has been reported as high as 98.5 % [10]. The agger nasi cell (ANC) represents the most anterior and constant frontal recess cell, located at the anterior boundary of the frontal recess. Supraorbital ethmoid cell (SOEC) may determine the frontal recess caliber from a lateral aspect. Traditional teaching holds the cell is present 6–15 % of the time, though recent work has demonstrated its presence in 62 % of cases [11]. SOECs pneumatize the orbital plate of the frontal bone posterior to the frontal recess and lateral to the frontal sinus. Thus, the SOEC ostium is located posterolateral to the frontal recess, whereas the frontal sinus ostium is usually in an anteromedial position. The supraorbital ethmoid cell has been incorrectly recognized as a septated frontal sinus; missed SOECs represent a frequent source of iatrogenic frontal sinus disease (Fig. 26.2).

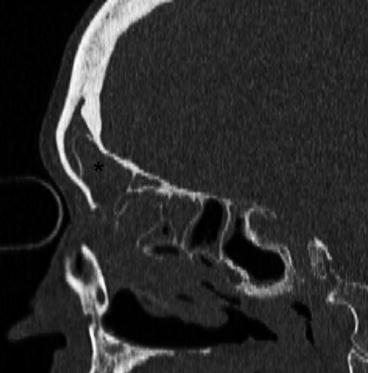

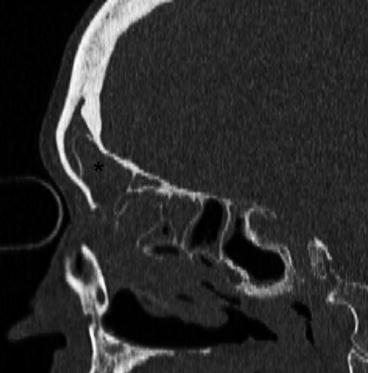

Fig. 26.2

Sagittal CT image depicts a type III frontal cell (asterisk) extending into the frontal sinus proper. The cell was dissected with standard endoscopic frontal instrumentation

Frontal cells are ethmoid air cells that pneumatize the frontal recess anteriorly and are found superior to the ANC. Bent and Kuhn grouped these cells into four different types based on their location: type I describes a single cell above the agger nasi, type II refers to a tier of two or more cells superior to the agger nasi, type III is a single cell that pneumatizes into the frontal sinus, and type IV is contained entirely within the frontal sinus [12]. Suprabullar and frontal bullar cells pneumatize along the skull base, residing above the ethmoid bulla, and encroach the frontal recess from posteriorly. The frontal bullar cell extends into the frontal sinus proper, while the suprabullar cell has the same configuration but does not extend into the frontal sinus. The intersinus septal cell is a midline cell that pneumatizes the frontal intersinus septum and may narrow the recess medially.

The physiology of the frontal sinus relies on normal mucociliary transport for drainage and ventilation. The frontal sinus is the only sinus in which an inherent recirculation phenomenon occurs wherein mucus is actively transported into the sinus superiorly along the intersinus septum and then travels across the frontal sinus roof to the lateral frontal sinus and finally medially along the frontal sinus floor. Approximately 60 % of the mucus recirculates to the intersinus septum, while 40 % is swept down into the middle meatus [13].

Decision Making in Frontal Sinus Surgery

The management algorithm for chronic frontal sinusitis commences when the disease is deemed refractory to maximal medical therapy. With widespread adoption of FESS techniques, the central concept of frontal sinus surgery has shifted from ablative to preservative approaches. The primary goals are preservation of mucosa of the frontal outflow tract and establishment of frontal ventilation and drainage. The following surgical options are currently available for treatment of frontal sinus disease:

Balloon catheter dilation (BCD)

Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy

Endoscopic frontal trephination

Endoscopic modified Lothrop

Osteoplastic flap (OPF) without obliteration

Osteoplastic flap with frontal sinus obliteration (FSO)

Riedel’s procedure

Some central tenets must be considered when formulating the surgical approach:

Majority of frontal sinus disease is amenable to endoscopic frontal sinusotomy.

Balloon catheter technology may serve as an adjunct in select cases.

Endoscopic frontal trephination may provide an additional porthole for difficult-to-reach frontal sinus pathology.

Frontal drillout procedures may be required for refractory disease with new-bone and/or scar formation in the setting of previous failed surgery.

OPF can be performed without obliteration.

Riedel’s procedure should be considered a last resort.

Frontal Instrumentation

The refinement of rigid endoscopes and advances in frontal instrumentation has been crucial for implementation of the endoscopic frontal surgery paradigm. The following instruments are critical for facilitating frontal sinus surgery:

Angled scopes (30°, 45°, and 70°)

Angled frontal recess suctions

Giraffe (grasping and thru-cutting) 60° and 90° forceps

Frontal 45° and 90° curettes

Frontal sinus seekers

Angled microdebrider attachments

Drills

Image Guidance

The advent of image-guided surgery (IGS) has been an important advance for management of frontal sinus disease. Preoperatively, image guidance enables triplanar review of the complex frontal recess anatomy, thus facilitating the ability to devise a detailed plan to the frontal sinus. Intraoperatively, IGS allows for sound execution of the surgical strategy and correlation of the preoperative imaging with the endoscopic anatomy. This, in turn, translates into a better safety profile with reduction in complications and more comprehensive frontal recess dissection. Despite its utility, surgical navigation platforms have inherent limitations and do not represent a substitute for intimate knowledge of the frontal sinus anatomy and sound surgical technique [14]. Further, mucosal preservation remains a paramount goal.

Postoperative Care

An important factor in the success of frontal sinus surgery rests on commitment to meticulous postoperative care and close long-term endoscopic surveillance. Saline irrigations are instituted on the first postoperative day. Antibiotics, preferably culture directed, and systemic steroids, if clinically indicated, are utilized until complete mucosal healing is achieved. The patients are typically seen weekly or biweekly with careful removal of fibrin clots and debris to ensure proper mucosal healing. Any early synechiae are lysed with thru-cutting frontal instrumentation to ensure frontal patency and to facilitate unobstructed endoscopic view of the internal ostium (Fig. 26.3) [15].

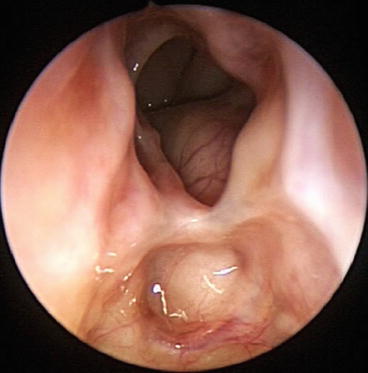

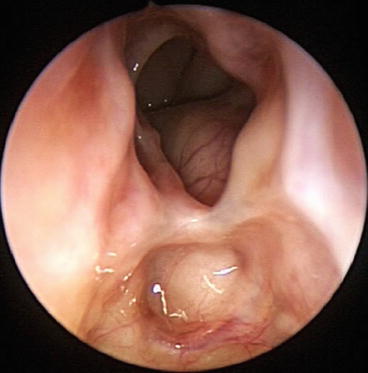

Fig. 26.3

Endoscopic view of healed right frontal internal ostium

Endoscopic Frontal Balloon Dilation

Indications

BCD of the sinus ostia is a relatively new tool in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). Data has suggested potential utility of this device for treatment of adult and pediatric medically refractory CRS, limited CRS, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis, and frontal sinusitis. Additionally, studies have also shown efficacy in the office and ICU setting [16, 17].

Surgical Technique

Balloon dilation devices may be used as the sole tool in select patients with isolated, unilateral frontal disease. Alternately, concurrent FESS may be performed to address disease in the adjacent sinuses or to achieve optimal exposure of the frontal recess to facilitate successful frontal dilation [18].

Topical and injected local anesthetic can be used for office-based BCD, while general anesthesia is often employed for cases in the operative suite. Balloon SinuplastyTM (Acclarent, Inc., Menlo Park, CA) employs the Seldinger technique under endoscopic visualization with 30°, 45°, and/or 70° telescopes. A guide catheter is introduced and positioned in the middle meatus posterior to the uncinate process, directed toward the frontal recess. A flexible guide wire is inserted through the guide catheter to cannulate the frontal sinus. Fluoroscopic guidance or a lighted guide wire can be used to confirm frontal sinus position. After successful cannulation, an uninflated balloon catheter is advanced over the wire into position at the frontal sinus ostium. The balloon is inflated and deflated sequentially along the frontal sinus drainage pathway. Alternatively, a newer balloon catheter is available with a malleable tip which can also serve as a frontal seeker and can be directed into the frontal recess under endoscopic visualization during sinus surgery (XprESSTM, Entellus Medical, Plymouth, MN). Once dilated by BCD, the sinus ostial region is inspected with angled telescopes to visually confirm successful dilation and patency [17, 19].

Outcomes

Catalano and Payne reported on the utility of BCD to achieve patency for frontal BCD performed on 29 frontal sinuses in 20 patients with medically refractory chronic frontal sinusitis. Success rate by disease subtype for aspirin triad, CRS with nasal polyps, and CRS without nasal polyps was approximately 36, 40, and 62 %, respectively. Viewed differently, this signifies a failure rate approaching 60–64 % in patients with hyperplastic disease and suggests that BCD may not be an appropriate intervention for frontal disease in patients with significant polyp burden [20].

Heimgartner et al. retrospectively evaluated BCD for medically refractory frontal sinus disease to determine the intraoperative technical failure rate and to analyze reasons for failed access. They noted failures in 12 % of cases, most commonly due to complex frontal recess pneumatization pattern or significant neo-osteogenesis [21].

There is a single randomized trial to prospectively evaluate BCD vs. endoscopic frontal sinusotomy for medically refractory frontal sinus disease in 32 patients. All patients were treated with hybrid procedures using multiple subjective and objective validated outcome measures. Resolution of frontal sinus disease was more common after BCD compared with Draf I or Draf IIa procedures (80.8 % vs. 75 %), and frontal patency was statistically more common after BCD (73.1 % vs. 62.5 %), although neither was statistically significant. The study suffers from several limitations, including lack of pretrial power analysis, selective reporting bias given failure to conduct a between-group analysis for multiple parameters, and omitting statistical data, such as p-values and confidence intervals. Nonetheless, this is an important step in the right direction with need for additional more robust studies comparing efficacy of BCD directly to FESS techniques [18].

Endoscopic Frontal Sinusotomy

Indications

Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy is considered the standard for surgical treatment of frontal sinus disease. This is used to address complicated acute sinusitis, chronic or recurrent frontal sinus disease with associated symptoms and radiographic findings, iatrogenic disease of the frontal sinus outflow tract, frontal sinus mucoceles, and limited frontal recess inverted papilloma.

Surgical Technique

Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy can be functionally defined as endoscopic removal of frontal recess cells to restore frontal sinus ventilation and drainage. This approach may include removal of frontal recess cells and/or the common wall between the frontal sinus and SOE cell.

Draf has defined a classification scheme from type I to III of progressively more extended frontal sinus surgery that can be adapted to the specific underlying pathology. Type I drainage is established by ethmoidectomy and serves to remove obstructing disease inferior to the frontal ostium. The frontal infundibulum and its mucosa are preserved, and the frontal sinus heals by improved drainage of the ethmoid cavity. Types IIa and IIb consist of enlargement of the frontal sinus outflow tract. Type IIa involves removal of ethmoid cells protruding into the frontal sinus to create a larger opening of the frontal sinus floor between the lamina papyracea and the middle turbinate. Draf type IIb involves extending the frontal sinus floor removal medially to the nasal septum to provide a maximal ipsilateral frontal opening. Draf type III, or endoscopic modified Lothrop (EML) procedure, creates a maximal bilateral frontal opening from orbit to orbit [22]. This is described in greater detail later in the chapter.

Key tenets in frontal recess dissection should be observed to optimize results.

1.

Careful review of the frontal recess anatomy is essential. Ideally, this should be a composite of the preoperative endoscopic examination and triplanar CT anatomy.

2.

The entire frontal recess dissection is performed with 30°, 45°, and 70° endoscopes.

3.

Limited or total ethmoidectomy should be first performed to create access for frontal recess dissection. In select cases, a complete anterior ethmoidectomy alone may resolve frontal sinus disease.

4.

Frontal recess dissection should proceed carefully from a posterior to anterior and medial to lateral direction to avoid inadvertent skull base penetration.

5.

All obstructive frontal recess cells should be gently fractured from posterior to anterior with curettes. Residual bony fragments should be carefully removed with angled giraffe forceps. Angled microdebrider blades should be used very judiciously given risk of inadvertent mucosal trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree