Strategies in Breast Reduction and Mastopexy After Massive Weight Loss

Dennis J. Hurwitz

Introduction

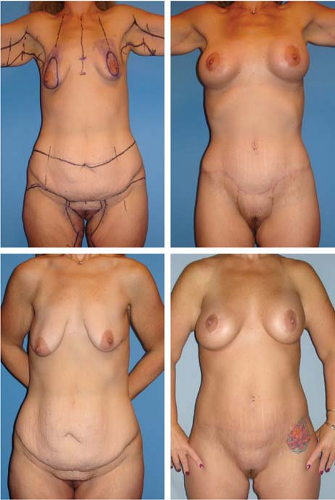

After massive weight loss (MWL), breasts are often ptotic and project poorly. The tissues can become so deflated and lax that the breasts resemble pancakes (Fig. 103.1). Depending on residual breast volume, breast reshaping consists of reduction, mastopexy, or mastopexy with augmentation.

The poor quality of the tissues and severity of the deformity makes these breasts not only difficult to reshape, but also prone to recurrent deformity. Compounding the MWL breast deformity is the surrounding loose skin of the arms, axillas, and torso. Hence, the strategy for treatment of MWL breasts involves not only effective and long-term improvement of its varied deformities, but also correction of the surrounding soft tissues of the torso and upper extremity.

With the increased popularity of bariatric surgery and public acceptance of plastic surgery, this clinical challenge is becoming common. After nearly a decade of focused clinical activity, I present a comprehensive, effective, and safe approach to aesthetically contouring the breasts and upper torso. A brief discussion of obesity, weight loss surgery, the subsequent contour deformities, and their treatment introduces my approach to the MWL breast.

Obesity and Weight Loss

Obesity is approaching epidemic proportions and causes about 300,000 deaths per year in the United States (1). From 2003 to 2004, 66.3% of American adults were classified as either overweight or obese, 32.2% were obese, and 4.8% were morbidly obese (2). The values of body mass index (BMI) used to define overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity are 25.0 to 29.9, 30.0 to 39.9, and greater than 40.0 kg/m2, respectively (3). Obesity is not only deforming, but it also is accompanied by a long list of adverse medical conditions that reduce the quality and length of life (4). While there are outstanding instances of massive weight loss by lifestyle change, weight loss surgery (WLS) is recognized as the effective long-term treatment for obesity and related comorbidities (5).

WLS results in a drastic reduction of food consumption by restrictive or malabsorptive means or by a combination of the two. The most common bariatric operations are laparoscopic adjustable banding (LAGB) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP). LAGB is a restrictive procedure in which a small gastric pouch with a small outlet is created, resulting in early and prolonged satiety (6). Since the normal absorptive surface is left intact, specific nutrient deficiencies are uncommon, unless vomiting is induced or there are eccentric dietary restrictions. The RYGBP procedure involves both restrictive and malabsorptive components. The stomach pouch is decreased to less than 30 mL with a roughly 100-cm Roux limb. WLS produces weight loss within 1 year after surgery that is three to four times superior to what can be achieved with nonsurgical weight management programs (7). Depending on the procedure employed, patients typically lose about 25% to 40% of their initial weight at 12 to 18 months and maintain the majority of the lost weight for many years (7). These numbers clearly represent a much greater and lasting change compared to other weight loss options. Consequently, the number of bariatric operations has risen progressively, with more than 200,000 procedures performed in 2007 alone (8). Altered food intake and malabsorption lead to a variety of protein, vitamin, and mineral deficiencies that can have significant impact on outcomes of subsequent plastic surgery (9,10).

The recent success of bariatric surgery has led to increasing numbers of individuals with sagging skin and body contours. Just for the massive weight loss patients, there were more than 68,000 body-contouring procedures in 2006 (11).

Weight Loss Deformity

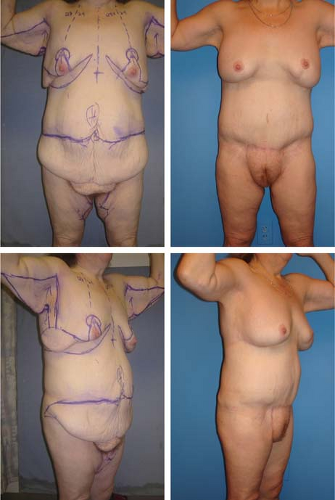

MWL leaves a spectrum of body deformity (Figs. 103.1 to 103.11). The skin laxity relates to the rapidity of reduction, absolute change, and final BMI. The deflation is influenced by age, general health, and fitness, as well as by familial and gender-specific fat depositions, skin elasticity, skin to fascia adherences, muscular development, and skeletal form. The complexity of the etiology thwarts precise predictions.

The susceptible regions are the anterior neck, upper arms, breasts, lower back, abdomen, mons pubis, buttocks, and thighs. Characteristically there is a large, sometimes transversely septated abdominal pannus overlapping the pubic and groin regions, with smaller rolls about the back, and in the upper medial and lateral thighs. Skin rolls are partially emptied, localized deposits of fat defined by transverse adherence of dermis to deep fascia. Wrinkled skin is emptied of fat. A roll of an entire region or structure is considered ptosis. Ptosis occurs in the breasts, mons pubis, and buttocks. These contour changes androgenize women and feminize men.

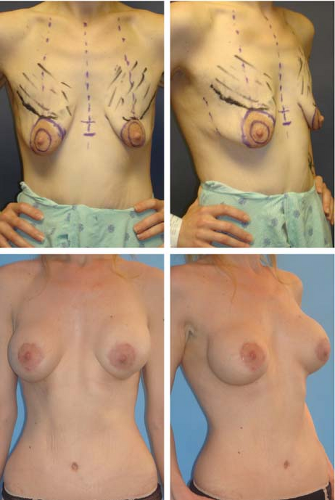

The breast shape, texture, projection, and skin elasticity deteriorate. The breasts flatten, sag, and descend slightly down the chest. Superior pole fullness is diminished to absent. With reduced fat, the organ feels firm and gritty. Broad areas of dermal striae are common. The breasts are displaced and broadened by descended inframammary folds (IMF). The IMF descent progressively increases from medial to lateral. The nipple-areolar complexes (NACs) are ptotic and may be distorted.

Surrounding the breasts are cascading rolls of mid torso skin with shaping influenced by transverse subcutaneous fascial adherences to underlying muscular fascia. The flattened anterior

axillary line ends at a hyperaxilla (oversized and deep) and canopy-like sagging upper arm.

axillary line ends at a hyperaxilla (oversized and deep) and canopy-like sagging upper arm.

Overlapping skin traps moisture, with increased bacterial counts and mal odor. Skin irritation leads from intertrigo to abscesses. Flapping tissues inhibit athletic activity. Large pannus and ptotic regions may cause poor posture and back strain. Clothes fit poorly. The unclothed presence is often more objectionable to the patient after MWL.

Principles of Body Contouring Surgery

Body contouring surgery is the removal of excess tissue while improving gender-specific contours (Fig. 103.12). My appreciation of the surgical principles of body contouring surgery after MWL has evolved (12,13,14). The torso is shaped by the transverse removal of excess skin, leaving level, flat, and symmetric scars that are hidden from view in minimal clothing. The reliable positioning of incisions that result in such favorable scars requires a consistent marking plan that includes multiple body positions, vigorous manipulation of the tissues, artistic visualization, and willingness to redraw lines until they seem precisely correct. With consistency and experience, the surgeon will gain confidence in the accuracy of the planned excisions and make minimal intraoperative adjustments, facilitating efficiency and teamwork.

Closure across the widest diameters of the torso, the IMFs, and hips takes in some of the transverse excess. Vertical or oblique excisions of skin along the torso or thighs are reserved for severe gynecomastia, intervening scars, hernias, or massive transverse skin and fat excess. The fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty can be applied to the unscarred abdomen, if that is the only procedure used to shape the anterior-lateral torso.

With the preinfusion of epinephrine-containing solutions, large-blade scalpel incisions are made through the skin and subcutaneous fascia. Electrocautery is reserved for direct coagulation of vessels and undermining to avoid thermal injury to the superficial fascial system (SFS). Direct undermining is limited, relying on the Lockwood underminer, liposuction, and dissector dilators for more distant discontinuous skin release. The undermining is adequate when the dermis, not the deep fascial adherences, limits pulling the flap toward closure.

Secure closures depend on closely spaced broad inclusion of the multilayered SFS by large braided sutures. With poor skin elasticity, closure of the SFS must be tight. Even so, a tight abdomen on standing may have flaccid rolls of skin upon sitting. As permanent suture closure of the subcutaneous tissues was strongly advocated by the body lift pioneer Lockwood (15), at first I used them regularly. Subsequent to a single case of multiple delayed suture abscesses from permanent sutures, I abandoned their use in 2006. I found braided absorbable suture closure adequate. Concerned about strangulating fat necrosis within an overly constricting interrupted suture and for speed of closure, I moved toward running braided suture closure. Suture breakage with unraveling of the closure was a concern. Over the last few years, I have switched to double-needle two-direction barbed sutures called Quill SRS (Angiotech, Vancouver, Canada) for more rapid and secure two-layer closures. Lower-body lifts are generally closed with no. 2 Quill polydioxanone (PDO) 24-cm-long sutures. The dermis is aligned with rapid-absorbing 3-0 or 2-0 barbed Monoderm. The absence of knots reduces suture-related infections; however, spitting sutures do occur due to large-gauge suture placed near the dermis. The tension during closure should be minimized by flexing the region. Preliminary alignment and placement of cross-hatching aids in accurate closure of the wound with running sutures. When an undermined flap is to be advanced to a

fixed point such as a reverse abdominoplasty flap to the sixth rib to create the new IMF or a medial thigh flap to the pubis, then all the interrupted sutures are placed first and later tied with the assistant pushing the tissues together.

fixed point such as a reverse abdominoplasty flap to the sixth rib to create the new IMF or a medial thigh flap to the pubis, then all the interrupted sutures are placed first and later tied with the assistant pushing the tissues together.

Overresection of skin followed by excessively tight closure leads to wound dehiscence or later to broadly depressed tissues due to suture pullthrough, breakage, or premature dissolution. The etiology of the common suture abscess with exposure of the suture is multifactorial (16). Localized wound infection with suture abscesses may be due to incision ischemia, intraoperative hypothermia, vasoconstriction, bacterial contamination, foreign-body reaction, intraoperative or postoperative pressure sores, suture characteristics, excessive surgical trauma, and reduced immune status. Prompt drainage and removal of the offending material and debridement of necrotic tissue is essential, followed by appropriate wound care. Our initial series of total body lift patients, when closely examined for every delayed healing, experienced nearly a 75% wound-healing complication rate (16). There has been a steady downward trend of wound complications with better selection of patients, correction of preoperative nutritional deficiencies, and maintenance of adequate postoperative nutrition, as well as improved maintenance of body temperature and positioning (12,16).

Inadequate removal of skin and low closure tension lead to failure. Even when the skin tension at closure is high and an appropriate lift and contour correction appears for some months, significant recurrence can occur 6 months later. This disappointing and unpredictable event is treated by repeat surgery.

Gender-specific convexity and concavity are thoughtfully sculptured. The fullness of the female hips and gentle convexity of the mons pubis and lateral thighs need to be preserved or reconstructed if lost. Body contour flattens along the line of tight closure or between nearby transverse closures. Therefore, lower-body-lift incision closure is rarely along the lateral trochanters, which might obliterate their natural convexity. Yet, a high suture line along the waist is too exposed for most patients. The waist is maximally narrowed between the upper and lower body transverse closures of the total-body-lift operation. Convexity is created by preservation of subcutaneous fat and, if needed, by adipose flaps or lipoaugmentation. An appropriate amount of fat should be preserved in the midline distal abdominoplasty flap and over the lateral pelvis to create a gentle feminine suprapubic and hip fullness.

Review of Massive-Weight-Loss Literature on the Breast

After intestinal bypass surgery for obesity became popular in the 1970s, Zook opined that once all indicated surgical procedures were identified, a surgical plan was coordinated “so that as many [procedures] as possible can be done simultaneously” (17). With two or three teams working at the same time, the arms, breasts, and circumferential abdominoplasty were contoured (17,18). The aesthetic interrelationship between the breast deformity and the arms and trunk was not discussed. In fact, Zook later declared post–weight-loss body contouring nonaesthetic, primarily due to the extensive scars (18). He considered loosely hanging breasts as “an extremely difficult problem” (17). He cited others’ and his experience, indicating that normally discarded flaps should be deepithelialized and placed behind the breasts. He favored the Pitanguy mastopexy with deepithelialization of the keyhole and the entire inferior breast, which was then turned upward to give the breast bulk and projection. For undesirable rolls and bulk, the inferior incision was carried around the trunk (17).

About the same time, Palmer et al. recommended procedures on only one area at a time because of the extent of each excision (19). Recognizing the skin folds below and lateral to the ptotic breasts, they built up the breast “using the loose tissue surrounding it” (19). They used the Wise pattern (20) and the popular McKissock (21) vertical deepithelialized bipedicle mammoplasty to gather the remaining glandular tissue under

the nipple. In all three reported patients, they combined this “with a wide excision of the submammary fold” (19). In 1979, Shons noted the variety of breast presentations after massive weight loss, preferring the McKissock technique with removal of excess skin through the Wise pattern (22).

the nipple. In all three reported patients, they combined this “with a wide excision of the submammary fold” (19). In 1979, Shons noted the variety of breast presentations after massive weight loss, preferring the McKissock technique with removal of excess skin through the Wise pattern (22).

During the 1980s, Lockwood elucidated the SFS and the need to approximate this multilayered fascia for high-tension closures of skin flaps (15). He stated that breast projection and scars were improved after reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy, when permanent suture closure of the SFS was performed (23). For tightening the loose IMF and improving breast projection, he advocated fixing the IMF at “the appropriate elevated position by nonabsorbable sutures from the SFS of the inferior skin wound edge to the underlying muscular fascia.”

The more recent mastopexy references will be presented in the next sections.

Evolution of Breast Technique

Until 10 years ago, I treated the breast deformity in isolation, considering neither the poor aesthetics nor the reconstructive potential of nearby skin excess. It became clear that circumferential abdominoplasty with a lower body lift was inadequate to correct laxity about the upper torso. Moving the belt-like excision higher to the flanks improved the mid torso rolls but reduced the lift on the lateral thighs. Furthermore, patients preferred the hip-hugging to the mid-waist scars. Removal of

the upper torso excess would be accomplished by a tight, nearly circumferential bra-line transverse excision of skin while preserving the flaccidity and projection of the breasts. The newly designed upper body lift would have to be in concert with the breast reshaping (24).

the upper torso excess would be accomplished by a tight, nearly circumferential bra-line transverse excision of skin while preserving the flaccidity and projection of the breasts. The newly designed upper body lift would have to be in concert with the breast reshaping (24).

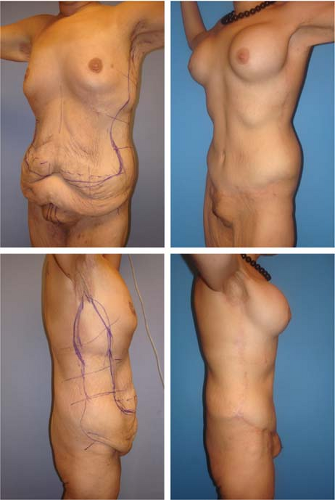

Coincident with seeking a solution to the breast and chest disorder, a better approach to the axilla and upper arms was needed. Leaving behind an oversized axilla, hanging arm skin, and a ptotic posterior axillary fold detracted from whatever breast improvement was achieved. An L-shaped brachioplasty was designed that addressed these issues and left a curvilinear inner arm scar that zigzags across the axilla to the lateral chest (25).

For breast atrophy, I relied on partial subpectoral placement of silicone breast implants, with usually a Wise-pattern mastopexy. Augmentation with mastopexy, complex and risk prone in the cosmetic patient, is described in the chapters of this text dealing with augmentation mammaplasty. The issues of recurrent ptosis, disassociation of implant, and gland and wound-healing complications are discussed by the experts. Currently, its relative simplicity, reliability, and surgeon familiarity make silicone implant augmentation with mastopexy a common method for increasing breast volume and improving shape. The problems with the MWL population are extreme atrophy and laxity, often with lowered breast position. An augmentation mastopexy for MWL patients usually leads to recurrent breast ptosis and bottoming out or displacement of the lower pole of the breast. Patients with good skin elastic recoil and smaller implants do better (Fig. 103.2).

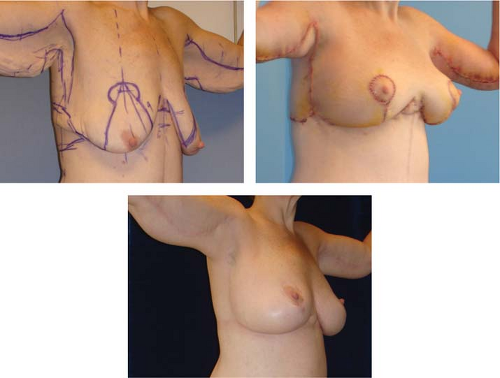

Figure 103.7. These are right anterior oblique views before and 3 days and 1 year after upper body lift, L-shaped brachioplasties, and spiral flap reshaping of the breasts in a 47-year-old 5′6″ tall, 207-pound (body mass index 33.80) woman. She had lost 220 of her 427 pounds through Roux-en-Y bypass surgery. Six months after her lower body lift, abdominoplasty, and vertical inner thighplasties, she had some minor revisions along with her upper body surgery. Left: The long vertical limb Wise pattern continues onto the epigastrium and lateral thorax as it passes the vertical descending lines of the L-shaped brachioplasties. The lower transverse line on the sternum registers the current level of the inframammary fold (IMF). The second transverse line is the projected new level of the IMF. Right: The reconstructed breasts and arms are tensely full. The nipple-areola complexes (NACs) are properly positioned at the prominence of the breasts with full superior poles. The fill of the lower poles required the entire 10 cm of vertical lines of the Wise pattern. Bottom: One year later the breasts and arms exhibit a more natural soft appearance with appropriate fill of the superior and inferior poles and no change in the position of the IMF or NACs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|