Sports Dermatology: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Skin problems are common among athletes.1,2 During an 8-week survey of university athletes, 40% reported skin problems.3 In a study of mountain biking injuries, skin lesions accounted for 75% of all injuries.4 Skin lesions account for 35% of all in-line skating injuries.5 Skin infections are more prevalent in athletes than in the general population.6 Skin-related complaints are especially common in warm, humid climates. During the 1993 Central American and Caribbean Games, held in Puerto Rico, one out of every hundred athletes had a skin-related complaint severe enough to require medical care.7 Similarly, sports that involve repeated immersion in water are associated with an increased incidence of skin injury and infection.8 Winter sports often involve short periods of repetitive injury resulting in a high frequency of injuries.9

Table 99-1 lists some unique sports-associated skin conditions that are worthy of mention but are not discussed further in this chapter (Figs. 99-1 and 99-2).

Bikini bottom: bacterial folliculitis on the buttocks of swimmers |

Jazz ballet bottom: buttock cleft abscess |

Jogger’s nipples: painful, swollen, eroded or hyperkeratotic nipples |

Karate cicatrices: linear scars on the dorsal aspects of the hands |

Mogul skier’s palm: traumatic hypothenar ecchymosis |

Painful piezogenic pedal papules: transdermal fat herniations |

Ping-pong patches: traumatic ecchymotic patches |

Pool palms: smooth, shiny, tender palms secondary to rough pool surfaces |

Pulling-boat hands: pernio-like condition produced by friction and damp cold |

Rower’s rump: lichenification |

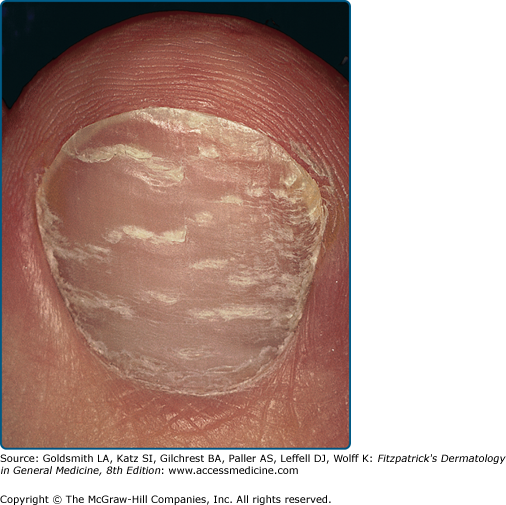

Runner’s nail: multiple Beau’s lines or periodic shedding of the nail plate (see Fig. 99-1) |

Runner’s rump: ecchymoses of the superior gluteal cleft |

Stingray hickey: bite ecchymosis |

Stretcher’s scrotum: scrotal hematoma |

Swimmer’s shine: facial oiliness seen in swimmers |

Swimmer’s shoulder: abrasion of the shoulder by the beard during crawl stroke |

Talon noir (black heel): intradermal hemorrhage |

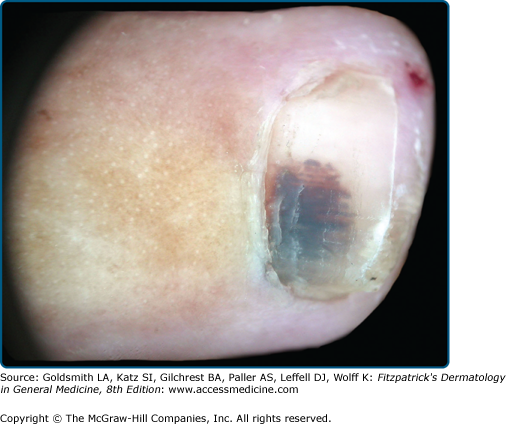

Tennis toe: subungual hematoma with or without subungual hyperkeratosis or nail dystrophy (jogger’s toe, hiker’s toe, skier’s toe are similar) (see Fig. 99-2) |

Turf toe: metatarsophalangeal joint sprain |

Pyogenic Skin Infections

Cutaneous community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has emerged as the most important pathogen among athletes.10–13 Athletes at risk include weight lifters, wrestlers, and members of competitive sports teams.14–16 During an outbreak of MRSA in a college football team, linemen had the highest attack rate (18%). Preexisting cuts or abrasions and sharing bars of soap were important risk factors associated with infection. Nasal carriage was associated with sharing towels, living on campus, having a locker near a teammate.17 Cosmetic body shaving has also been identified as a risk factor for MRSA infection.18 Data from an outbreak of MRSA abscesses among members of a professional football team (St. Louis Rams) indicates that most infections developed at turf-abrasion sites. Infection was significantly associated with the lineman or linebacker position as well as a higher body mass index. MRSA was cultured from whirlpools and taping gel as well as from 35 of the 84 nasal swabs from players and staff.19 In competitive male athletes, abscesses generally occur at sites of minor abrasions. In weightlifters, abscesses favor the axillae. Abscesses among female athletes favor the thighs and buttocks. Folliculitis and abscesses noted during an outbreak of MRSA in a saturation diving facility involved the nose, external ear canal, necks, back, extremities, and buttocks.20

MRSA isolates usually contain the type IV staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCC)mec coding for methicillin resistance, as well as the Panton-Valentine leukocidin virulence factor. There is a high risk of colonization in close contacts of individuals with MRSA, and those who are colonized commonly progress to clinical infection.21,22 Sharing of towels and higher body mass index are independent risk factors for MRSA infection.23

MRSA infection in athletes typically presents as folliculitis or spontaneous abscess (see Chapters 176 and 177). Abscesses may begin as furuncles but rapidly evolve to fluctuance with surrounding cellulitis.

Like other abscesses, MRSA abscesses respond to drainage. Surveillance data from Baltimore, Atlanta, and Minnesota including 1,647 cases of CAMRSA infection show that therapy to which the strain was resistant was not associated with adverse patient-reported outcomes if the abscess was incised and drained.24 Other data also suggest that many MRSA abscesses respond to drainage alone.25,26 Failure to drain MRSA abscesses may have catastrophic results, even if effective antibiotic therapy is prescribed. In one report, bilateral blindness resulted.27

Although the SCCmec type IV gene cassette present in most MRSA strains codes only for methicillin resistance, an isolate from a Japanese athlete also contained a transmissible plasmid coding for multiple-drug resistance.28 Other MRSA isolates have emerged that are resistant to multiple antibiotics. Some MRSA isolates from Taipei carry a distinct SCCmec cassette (type VT) that codes for resistance to multiple antibiotics.29 While drainage will cure many MRSA abscesses, some athletes will require antibiotic therapy. Of the inexpensive oral agents available to treat MRSA infections, sulfa drugs consistently show the best mean inhibitory concentrations. Tetracyclines are good alternative agents, although only about 80% of MRSA will be sensitive in many locations. Lincosamide resistance is increasing.30–32 Inducible resistance, related to the erm gene, results in strains that test clindamycin-susceptible in vitro, but may be resistant in vivo. A D-test can be used to determine the presence of inducible resistance. In the D-test, clindaymcin and erythromycin disks are placed close together on a culture plate. If inducible lincosamide resistance is present, the zone of inhibition around the clindamycin disk is flattened on the side towards the erythromycin disk, resembling a capital letter D. Rates of inducible lincosamide resistance vary from 8% in Houston to 94% in Chicago.33–37 In some areas in the United States, MRSA strains were less likely than methicillin-sensitive strains to demonstrate inducible resistance.38 In contrast, some locations in Asia report that 100% of tested MRSA strains demonstrate the ermB gene.39

Some serious MRSA infections will require the use of linezolid, vancomycin, fluoroquinolones, daptomycin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, or newer generation carbapenems. Fluoroquinolones and linezolid, have the advantage of oral administration. In some groups of severely ill patients, linezolid has proved superior to vancomycin.40–42 Daptomycin has been used effectively in serious MRSA infections, but resistance has been reported, and disk diffusion testing may not predict clinical outcome.43,44 A new cephalosporin, ceftobiprole medocaril appears to offer a good balance of efficacy and tolerability.45

Nasal colonization correlates poorly with cutaneous MRSA infection, suggesting that other sites of carriage and close physical contact with carriers are important in disease transmission.46 Cutaneous carriage and fomites are important in the spread of MRSA infection among athletes, and preventive measures directed only at nasal decolonization are frequently ineffective.47,48 Topical antiseptics such as chlorhexidine, povidone iodine, quaternary ammonium compounds, triclosan, and Dakin’s solution play an important role in management.49 Chlorhexidine gluconate is widely used and generally has good activity against staphylococci. Some MRSA isolates are less sensitive to chlorhexidine than methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) isolates.50,51 Some chlorhexidine-resistant isolates also exhibit resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds. Resistance can be overcome by using disinfectants containing both alcohol and chlorhexidine.52 Seventy percent ethanol alone is an effective agent for fomite sterilization if contact can be maintained for 3 minutes.53 Povidone iodine has shown good activity against both MRSA and MSSA isolates.81 Triclosan-based products are readily available as “no-wash” hand sterilizers. Some triclosan resistance has been documented, and some MRSA isolates are less sensitive than MSSA isolates.54,55 Mupirocin is commonly used to treat staphylococcal nasal carriage, but resistant strains have emerged.56 In one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, successful nasal eradication was only 44%.57

Group A streptococcal infections may also spread rapidly among athletes. Pyoderma with a nephritogenic Streptococcus can cause epidermic glomerulonephritis. Streptococci also produce erysipelas and lymphangitis (see Chapters 177 and 178).

Pseudomonas infections are commonly associated with water. Pseudomonas folliculitis, green nails, and Pseudomonas webspace infection are the most common (see Chapter 180 and online edition).

Viral Skin Infections

Herpes simplex virus (see Chapter 193) can be transmitted by skin-to-skin contact during any contact sport. Herpes gladiatorum is recognized as a major problem among wrestlers. Attack rates as high as 34% have been reported. Ocular involvement is a serious complication. Wrestlers with active infections are barred from participation. The use of abrasive shirts may contribute to the spread of herpes simplex virus infection among wrestlers. They should be avoided. Oral antiviral drugs such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir can be used to shorten the course of an outbreak. It is likely that all three of these drugs can prevent outbreaks of herpes gladiatorum when given as long-term or periodic prophylaxis.

Fungal Infections

Cutaneous fungal infections are more common among athletes than in the general population, and are particularly common among swimmers and soccer players.58,59 Tinea facei and tinea capitis are particularly common among wrestlers and others who engage in close contact sports.60,61 During an outbreak of Trichophyton tonsurans tinea in Japan, 52% of the patients were Judo participants and 39% were wrestlers.62 Asymptomatic carriage and poor compliance with eradication regimens is common in this setting and contributes to the spread of the disease.63–65 Many of the implicated strains were recently imported to Japan, spread first through martial arts, then to the community at large.66 Tinea pedis may be spread by floors around swimming pools. Prevalence among runners increases with age, and asymptomatic carriers are common. Periodic prophylactic treatment of carriers with topical agents to prevent clinical disease may be possible, and oral prophylaxis with 100 mg of fluconazole daily for 3 days twice during the season has been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of fungal infections among high-school wrestlers. In one study, the incidence rate of tinea gladiatorum dropped from 67.4% to 3.5% as a result of intervention.67

Transmission of Blood-Borne Pathogens

There is growing concern about possible transmission of blood-borne pathogens during contact sports. Minor cuts and abrasions are both a source of contamination and a portal of entry for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis viruses. Lacerations can be covered with self-adherent biosynthetic dressings to prevent blood transmission from minor wounds during contact sports.

Heat and Cold Injury

Heat injury is a common cause of morbidity during sports. The skin serves as the major organ of thermal regulation. Regular exercise modifies the responsiveness of cutaneous vessels, increasing cutaneous perfusion during periods of activity.68 The duration of exercise can be safely increased in hot environments if a volume of fluid at least equal to that lost in sweat is ingested within 60 minutes prior to and during exercise.69 Uniforms promote heat retention, and adequate skin surface must be exposed during exercise in order to reduce the risk of heat stress injury. Evaporative cooling from forearm skin is more efficient than that from the upper trunk; therefore, short sleeve uniforms are helpful in hot climates.70 Clothing should be lightweight and have high water permeability in order to facilitate evaporative cooling. At high humidity, evaporative cooling from skin is inefficient and the risk of heat stress increases. Spraying of water on the skin during exercise can reduce skin temperature, but results in vasoconstriction and does not reduce core body temperature.71 Cooling vests can improve athletic performance in hot weather.72,73 Harlequin syndrome is a disorder of the sympathetic nervous system with diminished sweating and flushing in response to exercise.74

Younger athletes have a greater skin surface area, which places them at greater risk for hypothermia in cold environments. Skin injury, such as frostbite and perniosis, are seen in sports enthusiasts who engage in cold weather sports. Frostbite is a common problem among joggers, and may involve the face, hands, feet and penis. The decreased oxygen tension at high altitudes contributes to peripheral vasoconstriction, decreasing peripheral blood flow and increasing the risk of frostbite.75 Clothing must remain dry in order to retain its insulating properties. Frequent changes of socks and periodic breaks in a warm environment are important safeguards. If frostbite occurs, rapid rewarming should be accomplished as soon as the individual is in a safe environment with no risk of refreezing.

Skin Injuries

Skin and soft tissue injuries are common among athletes.76,77 New treatments, including hydroactive wound dressings, have advanced the treatment of superficial wounds. Application of a hydroactive dressing can provide a protective barrier that can allow an athlete to return to training. Cold gel application has been shown to provide effective symptomatic relief for sports-related soft tissue injuries.

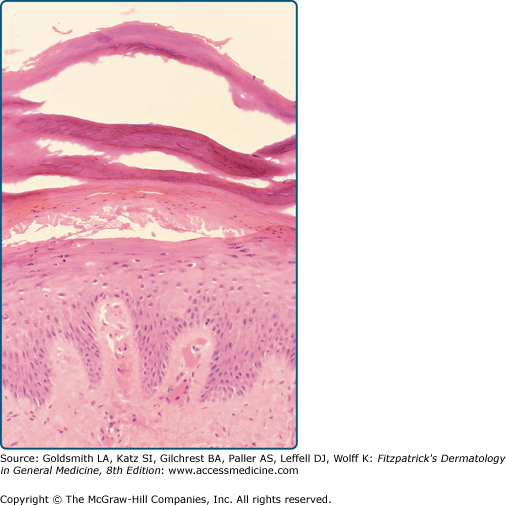

Friction blisters occur as a result of midepidermal necrosis (Fig. 99-3). Proper fitting of footwear and the use of gloves and chalk can reduce the incidence of blistering. Heat, sweating, and maceration increase the risk of blistering. Antiperspirants have been used in an attempt to reduce the incidence of blistering, but results have been mixed, and they may cause irritant dermatitis. Attempts to reduce the incidence of irritant dermatitis through the addition of emollients reduce the efficacy of the antiperspirant. In a study of cross-country hikers, use of a 20% solution of aluminum chloride hexahydrate in anhydrous alcohol reduced the rate of blister formation from 48%–21%, but the incidence of irritant dermatitis was high and noncompliance with the treatment regimen was common. The use of closed-cell neoprene insoles, acrylic socks, or thin polyester socks combined with thick wool or polypropylene socks that maintain their bulk can reduce the incidence of blisters. The use of mesh-top footwear can decrease the risk of blistering by providing a cooler, dryer environment without the use of antiperspirants. A unique form of friction dermatitis occurs in Sumo wrestlers.78