Special Problems in the Treatment and Reconstruction of Breast Cancer

Albert Losken

Introduction

The management of women with breast cancer continues to evolve, and along with that reconstructive standards and expectations are increasing. Newer techniques and newer technology have become essential to reduce potential morbidities and improve cosmetic results. We are now seeing a greater diversity of potential candidates for reconstruction and are subsequently reconstructing more patients with the entire spectrum of breast size, shape, and body habitus. Women with very small, ptotic, or very large breasts pose unique challenges throughout the treatment process from initial workup and diagnosis of the breast cancer to the completion of the reconstructive process. The treatment and reconstruction of breast cancer in these situations will be discussed in this chapter.

Thin Patients

Small Breasts

Breast reconstruction in thin women with small breasts poses unique challenges in that the available autologous donor tissue is often limited, and matching a contralateral small breast is difficult. These patients are typically younger and have active lifestyles. As part of the preoperative discussion it is important to address the patient’s desires for her ideal breast size prior to discussing the reconstructive procedure since an augmented contralateral breast would increase the reconstructive options.

Autologous Tissue Reconstruction

In patients who wish to match a small contralateral breast, limitations exist in terms of donor sites. If a small lower abdominal panniculus exists, free tissue transfer from the abdomen becomes an option. Generally 200 to 300 g of tissue can be harvested from a relatively thin abdomen, which is often enough to match the opposite side.

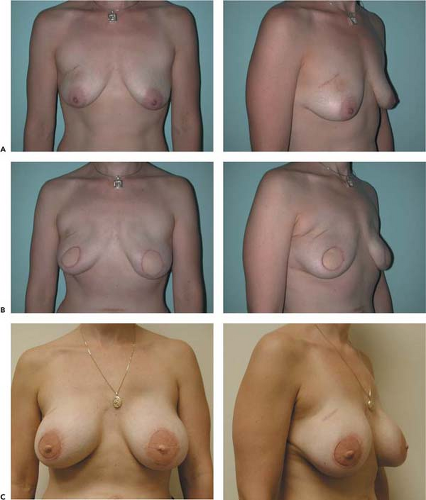

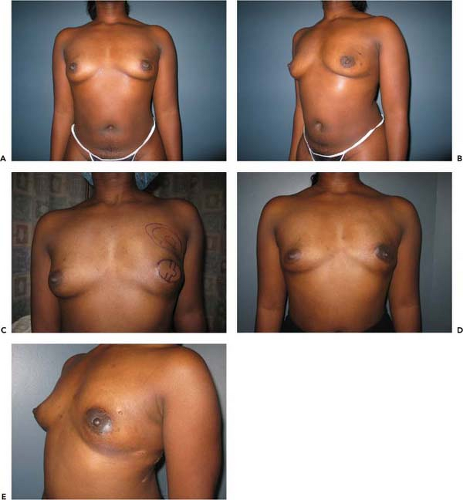

Preoperative marking of the inframammary fold is critical, as this is often obscured in women with small breasts, especially following mastectomy. The upper transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM) flap incision is extended laterally, and flap dissection is beveled away from the flap to incorporate adjacent subcutaneous tissue for added bulk. In an attempt to preserve as much volume as possible, more zones (I to IV) might be recruited, stressing the importance of maximizing blood flow and selecting those patients without additional morbidities such as abdominal scars and smoking effects. Attempted closure should always be performed in the semi-Fowler position prior to committing on flap size. Making the flap too wide in an attempt to adequately fill the pocket without considering tension on the donor-site closure will cause unnecessary problems with donor morbidity. Implants can always be added at a later stage rather than attempting to remove too much tissue (Fig. 13.1). The extended free TRAM recruits the lateral extensions, which even in thin patients can provide sufficient volume and projection for bilateral reconstructions (1). The free muscle-sparing TRAM is often the procedure of choice in these patients with small breasts, given the superior flap perfusion, as well the preservation of the inframammary fold. Pedicled TRAM flaps are not ideal, in that disruption of the inframammary fold (IMF) in women with small breasts often leads to lack of lower pole definition. Tunneling a pedicled flap either ipsilateral or contralateral into a small breast pocket will often obscure the inframammary fold. Secondary recontouring of the IMF at the time of nipple reconstruction is difficult. Superficial inferior epigastric artery flaps provide minimal donor morbidity and are an excellent option when the vessels are large enough (2).

When the abdominal tissue is in position, the edges can be folded in a transverse orientation to autoaugment breast size, especially in the smaller mastectomy pocket. If the pocket is wide (i.e., following axillary node sampling), shaping sutures are often necessary to close the pocket or appropriately position the flap for maximal shape and projection. In women who have very tall, slender, and narrow chests, longitudinal or oblique orientation of the flap will provide better shape without loss of superior fullness.

Even thin patients occasionally have sufficient back tissue to be candidates for an extended autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction (Fig. 13.2). There can be some fatty deposits over the trapezius muscle and above the iliac crest that provide bulk to the flap. The skin island is dissected down to Scarpa’s fascia, and subfascial fat is kept on the muscle for added volume. Preservation of the subdermal plexus (with >1 cm of layer of fat) is important to provide blood supply to the remaining skin once the perforating vasculature of the latissimus has been removed. In thin patients, the muscle pedicle is often noticeable, making the breast appear wide. The humeral insertion is taken down, and sub-Scarpa fat is not preserved in the axilla to prevent axillary fullness. Attempts to minimize seroma formation in thin patients include using 10-mm Blake drains for 2 to 3 weeks, using resorbable quilting sutures from the skin flaps to the chest wall, and possibly spraying the cavity with Tisseel spray prior to closure. This has reduced the postoperative drainage in patients at our institution. Autologous fat injections can augment the breast minimally at the second stage if necessary (see Fig. 13.2).

The superior gluteal flap, although technically more difficult and less forgiving, is a reasonable alternative in thin patients who are not TRAM flap candidates. It can provide descent volume and projection (3). The transverse myocutaneous gracilis

muscle flap is another option in women without sufficient abdominal fat that has been successfully used for postmastectomy breast reconstruction (4).

muscle flap is another option in women without sufficient abdominal fat that has been successfully used for postmastectomy breast reconstruction (4).

Bilateral mastectomies in thin patients with small breasts are often more difficult to reconstruct using abdominal flaps, given lack of sufficient tissue, especially in those patients with a relatively wide chest wall and some breast ptosis. Bilateral gluteal flaps or autologous latissimus dorsi flaps can be used when donor tissue is available.

Implant Reconstruction

Implant reconstruction is possible as a single-stage procedure if the patient’s breasts are small (A or small B cup), round, or in bilateral reconstructions. It is important to mark the inframammary fold bilaterally as this will assist with positioning of the implant. Fold asymmetry in the small, nonptotic breast will be noticeable postoperatively. Although round implants, when relatively small, will often provide decent shape, anatomic

implants can provide more lower pole fullness if this is required to match the opposite side (5). The submuscular pocket is created from the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle. The serratus anterior is also elevated for better implant coverage and prevention of lateral displacement if an axillary dissection is performed or if the mastectomy defect extends laterally. The pectoralis muscle is released inferiorly to allow lower pole projection of the implant. An acellular dermal matrix is sutured to the IMF inferiorly and the pectoralis muscle superiorly for more lower pole coverage and better projection. The skin is then closed in layers over a drain either horizontally or in a purse-string fashion. A contralateral procedure is not necessary in breasts with minimal ptosis and if the patient has no desire to have larger breasts. In women with small breasts and moderate ptosis (greater than 2 cm), a contralateral mastopexy or mastopexy/augmentation is often required to ensure symmetry.

implants can provide more lower pole fullness if this is required to match the opposite side (5). The submuscular pocket is created from the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle. The serratus anterior is also elevated for better implant coverage and prevention of lateral displacement if an axillary dissection is performed or if the mastectomy defect extends laterally. The pectoralis muscle is released inferiorly to allow lower pole projection of the implant. An acellular dermal matrix is sutured to the IMF inferiorly and the pectoralis muscle superiorly for more lower pole coverage and better projection. The skin is then closed in layers over a drain either horizontally or in a purse-string fashion. A contralateral procedure is not necessary in breasts with minimal ptosis and if the patient has no desire to have larger breasts. In women with small breasts and moderate ptosis (greater than 2 cm), a contralateral mastopexy or mastopexy/augmentation is often required to ensure symmetry.

A two-staged expander reconstruction is also an excellent option using a similar technique as mentioned previously and is often preferred in patients with small breasts where skin tension is a concern postoperatively. This will allow controlled postoperative expansion to the desired size, with secondary implant placement. Textured anatomic expanders with integrated valves have demonstrated less capsular contracture and valve dysfunction and provide lower pole expansion. An initial amount of saline is added to the expanders intraoperatively depending on the status of the skin flaps and muscle tension. Expansion is then started in the office 2 weeks postoperatively and progressed as tolerated. Implant exchange with a round or contoured silicone implant is performed secondarily.

Autologous Fat Transfer

Although under investigation, breast reconstruction using autologous fat injections might prove to be very useful in women with small breasts where only a limited amount of fat would be required to match the opposite side. It has been a very useful option as an adjunct to other reconstructions, especially in thin patients, where flap volume is often limited.

Breast Conservation Therapy

Breast preservation in women with small breasts who require a resection over 20% of their breast volume will often result in unfavorable cosmesis. Options include local flap reconstruction using oncoplastic techniques if breast conservation therapy (BCT) is desired (6,7) or skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) and immediate reconstruction. Reconstructing the lumpectomy defect using autologous fat grafting, which is processed to create a mixture of concentrated fat cells and stem cells, is a technique that is under investigation (8).

Large Breasts

The reconstructive options in thin patients with small breasts who desire larger breasts or thin patients with large breasts involve the addition of implants and the need for a contralateral procedure in unilateral reconstructions.

Autologous Reconstruction

The same autologous options do exist with the aforementioned limitations. However, the addition of an implant is often required to augment the breast size. This can be placed beneath the abdominal flap or the latissimus dorsi flap (9). The implant contributes less to the overall size and shape of the breast with TRAM flap coverage. The subcutaneous fat on the TRAM closely resembles that of native breast tissue and will not atrophy with time; instead, it fluctuates in size and shape with the patient’s weight and opposite breast. Flap compromise following free TRAM flap coverage of implants has not been demonstrated; however, seroma cavities can occur (10,11). Coverage of the implant with a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap will rely more on the implant for size and shape as muscle atrophy generally occurs. Implants can be placed beneath the pectoralis muscle for better muscular coverage, especially in thin patients with thin skin. Overzealous size augmentation following SSM is fraught with difficulties related to wound dehiscence and native breast skin flap necrosis. If moderate enlargements were desired, it would be safer to use tissue expanders and or increase the size of the skin island. Placement of the implant can also be performed secondarily if radiation therapy is anticipated or if the contralateral procedure is delayed. Management of the contralateral breast in the unilateral reconstructions for thin patients desiring larger breasts will typically require implant augmentation with or without mastopexy. This can be performed at the time of reconstruction or as a secondary procedure, depending on personal preference. I prefer to perform the symmetry procedures at the time of reconstruction, as it is easier to match the adjusted opposite breast with the reconstruction than vice versa unless radiation therapy is required.

In thin patients who already have large breasts, the aforementioned techniques are also applicable. Implants can be added to autologous tissue if size maintenance is desired; otherwise contralateral breast reduction will allow the reconstruction of a smaller breast, which might make pure autologous tissue reconstruction possible.

Implant Reconstruction

Implant reconstruction is possible if the opposite breast is augmented or round and full with minimal ptosis. It is more difficult to match a large, ptotic contralateral breast with implants alone. Even following breast reduction procedures, symmetry with implants alone in thin patients with large breasts is difficult to obtain, especially long term, as the breasts will age differently.

Obese Patients

Obesity increases the risk of breast cancer and is associated with advanced-stage breast cancer and poorer prognosis (12,13). We are subsequently seeing more obese women requesting reconstruction. Reconstructive options in obese patients are limited not by available tissue but rather by the inherent risks associated with surgical complications. Mastectomy with axillary node dissection alone in the obese patient is associated with increased risk of seroma formation and wound infection (14). It is important that the surgeon discuss the risks and benefits of the surgery preoperatively. Obese patients have an increased incidence of pulmonary, thrombotic, anesthetic, infectious, and metabolic perioperative complications (15) and are often considered poor candidates for breast reconstruction. These patients are often disappointed with their overall appearance and subsequently dissatisfied with their results. Patient expectations, limitations of the

surgery, and the need for additional procedures should all be discussed. Given the presence of one risk factor already, stringent patient selection and evaluation of additional risk factors are important to minimize postoperative complications.

surgery, and the need for additional procedures should all be discussed. Given the presence of one risk factor already, stringent patient selection and evaluation of additional risk factors are important to minimize postoperative complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree