Fig. 7.1

Illustration of sleeve gastrectomy

Although the procedure is technically simple, its complications such as staple line leak can be very serious and difficult to treat, even life threatening. Lack of technical standardization will result in poor outcomes. With the surgeons’ required technical experiences and knowledge, the standardization of procedure is mandatory for the excellent outcome of this procedure. However, there is so far no standardization in surgical techniques regarding sizing the sleeve, the first and last firing sites, staple line reinforcement, and so on.

7.2 Indications

The general indication of sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity is similar to that of gastric banding or LRYGB:

1.

Body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2 or BMI >35 kg/m2 with significant comorbidities

2.

BMI >37 kg/m2 or BMI >32 kg/m2 with significant comorbidities (Asia-Pacific)

3.

Failed attempts at nonsurgical weight loss

However, specific considerations can be posed to selection of sleeve gastrectomy.

First procedure in staged surgery in high-risk patients:

1.

Super-super-obese patients (BMI >60 kg/m2)

2.

Morbidly obese patients with significant comorbidity such as liver cirrhosis, Crohn’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or rheumatoid arthritis

Primary bariatric surgery:

1.

Lower BMI

2.

Adolescent or elderly morbidly obese patients

3.

Gastric lesions: Helicobacter pylori infection, ulcer, and chronic atrophic gastritis

4.

Desire to undergo a relatively simple restrictive operation not requiring the placement of a foreign body

5.

Necessity to continue specific medication (immunosuppressant, anti-inflammatory)

6.

Revisional surgery after gastric banding failure

Sleeve gastrectomy may be contraindicated in patients with:

1.

Severe gastroesophageal reflux disease or large hiatal hernia

2.

Barrett’s esophagus

3.

Ulcer located in the lesser curvature of the stomach

4.

Common relative contraindicated patients for LRYGB

7.3 Surgical Technique

7.3.1 General Setting

The general settings such as anesthesia, surgical team, and instruments for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy are similar to those described in the “basic techniques and instruments.”

7.3.2 Patient Position

Under general anesthesia, patient is positioned in reverse Trendelenburg position with slight left side up to facilitate operative field exposure. Urinary catheter and sequential compression devices are placed. Generally the operator stands at the right side of the patient with the camera operator and the first assistant at the left side with scrub nurse.

7.3.3 Port Placement

Introduction of first trocar to creating pneumoperitoneum is one of the most critical procedures which can be lethal during bariatric surgery. There are three methods:

1.

Use of Veress needle

2.

Open method

3.

Use of visual trocar

A transparent trocar is used, through which a camera tip can be inserted. The trocar and zero-degree camera are inserted simultaneously through the abdominal wall under laparoscopic view of abdominal wall layers.

CO2 gas is insufflated to create pneumoperitoneum to set the intra-abdominal pressure approximately 15 mmHg.

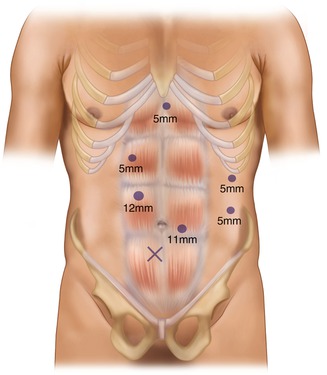

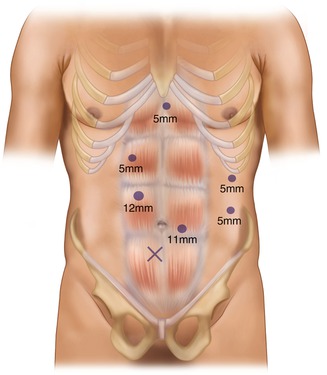

Generally the number of ports can be variable from five to six ports. Recently some surgeons try to perform the procedure using single incision or through the vagina (NOTES). It usually depends on the degree of patient obesity and surgeon’s preference. The location and size of ports are also different from cases to cases. The usual port placement is illustrated in Fig. 7.2.

Fig. 7.2

Port placement (six ports)

7.3.4 Liver Retraction

In order to get a good exposure around gastroesophageal junction, effective liver retraction is critical. Restricted calorie intake for at least 2 weeks before surgery may reduce left lateral segment volume of the liver. Several methods are used to retract the liver. Three-finger or five-finger liver retractor, snake retractor, or Nathanson liver retractor is frequently used. Suture technique is also available, but it is hard to apply to super obese patients.

7.3.5 Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

7.3.5.1 Starting the Dissection of the Greater Curvature

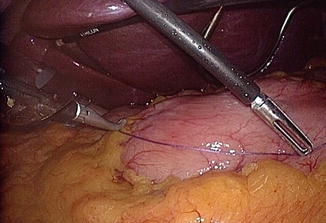

The pylorus is identified. The starting point of future stapling should be 2–8 cm away from the pylorus, and it should be marked beforehand (Fig. 7.3). It is easy to make the first window between the stomach and greater omentum at a slight proximal site away from the starting point (Fig. 7.4). The distal stomach is grasped and pulled to the right and upper, and then the greater omentum is spread to the counter-direction. Ultrasonic coagulating shears (e.g., Harmonic ScalpelTM) or vessel-sealing system (e.g., LigaSure) is useful to divide small vascular arcades of great omentum from the greater curvature of the stomach. Dissection is continued to get approach to short gastric vessels near the lower pole of the spleen.

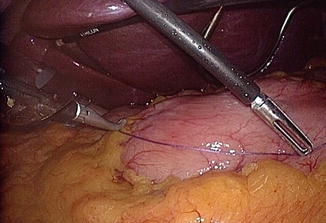

Fig. 7.3

Starting point is measured about 4–5 cm away from the pylorus

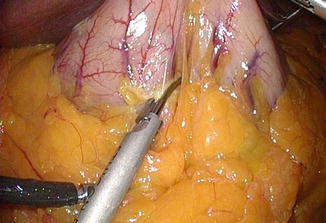

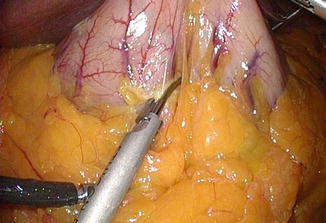

Fig. 7.4

Dissection begins by making a window at a transparent area between arcade and it is easier to start dissection from the proximal to the marking point

7.3.5.2 Mobilization of the Fundus

The short gastric vessels should be divided near to the gastric wall carefully with least tension between the stomach and spleen. Otherwise, bleeding with spleen capsule tearing may occur (Fig. 7.5). All division must be carried out under direct vision, not by blind or blunt dissection. The gastrophrenic ligament should be incised to ensure complete mobilization of fundus. The dissection is continued to the point of His angle and left diaphragmatic crus (Fig. 7.6). Sometimes, removal of fat pad around gastroesophageal junction may facilitate the exposure of left crus. Pulling the dissected fundus to the right and cranial and taking down the greater omentum to the left would make it easy to expose and dissect His angle area. Detachment of the posterior adhesion between the stomach and pancreas is important in order to remove the fundus completely and to make a good gastric tube having even anterior and posterior gastric wall (Fig. 7.7). However, too much mobilization might cause a twist of the gastric tube later. One should pay attention not to injure the blood vessels on lesser curvature including left gastric artery. The presence of hiatal hernia should be assessed, and if present the hiatus should be repaired.

Fig. 7.5

Short gastric vessel division close to gastric wall. Tension between the fundus and spleen should be minimized to prevent splenic tear

Fig. 7.6

Left diaphragmatic crus should be exposed for the complete removal of gastric fundus

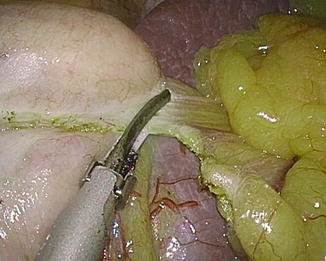

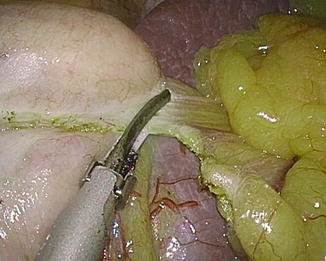

Fig. 7.7

Posterior adhesion should be detached in order to make a good sleeve

7.3.5.3 Transection of the Stomach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree