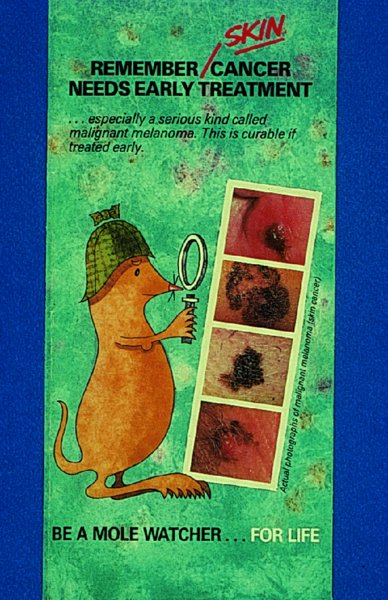

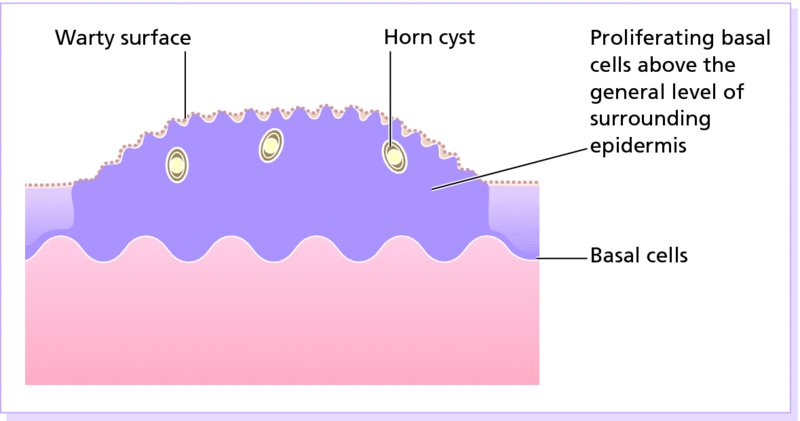

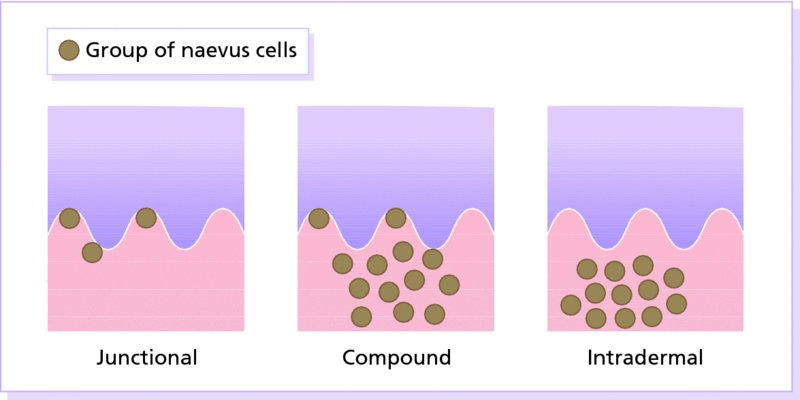

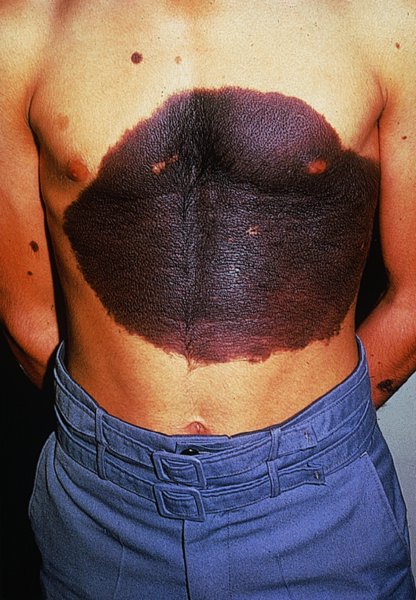

20 This chapter deals both with skin tumours arising from the epidermis and its appendages, and from the dermis (Table 20.1). Table 20.1 Skin tumours. Many skin tumours (e.g. actinic keratoses, lentigines, keratoacanthomas, basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, malignant melanomas and, arguably, acquired melanocytic naevi) would all become less common if Caucasoids, especially those with a fair skin, protected themselves adequately against sunlight. The education of those living in sunny climates or holidaying in the sun has already reaped great rewards here (Figure 20.1). Successful campaigns have focused on regular self-examination and on reducing sun exposure by avoidance, clothing and sunscreen preparations (Figures 20.2 and 20.3). Public compliance has been encouraged by imaginative slogans like the Australian ‘sun smart’ and ‘slip, slap and slop’ (slip on the shirt, slap on the hat and slop on the sunscreen) advice and the American Academy of Dermatology ‘ABCs’ (away, block, cover up, shade) leaflet. Figure 20.1 This family lived in the tropics. No prizes for guessing which of them avoided the sun. Figure 20.2 An eye-catching and effective way of teaching the public how to look at their moles. A pamphlet produced by the Cancer Research Campaign in the United Kingdom. Figure 20.3 These Scottish schoolchildren attending an Australian school were surprised to find that wide-brimmed sun protective hats were a compulsory part of the school uniform. These are fashionable after several clever campaigns, and the ‘no hat, no play’ rule has become an accepted way of life. These are discussed in Chapter 13, but are mentioned here for three reasons: first, solitary warts are sometimes misdiagnosed on the face or hands of the elderly; and, secondly, a wart is one of the few benign tumours in humans that is, without doubt, caused by a virus, the human papilloma virus (HPV). Thirdly, some HPVs are prime players in the pathogenesis of malignant tumours. Seventy per cent of transplant patients who have been immunosuppressed for over 5 years have multiple viral warts and there is growing evidence that immunosuppression, certain types of HPV and ultraviolet radiation interact in this setting to cause squamous cell carcinoma (p. 292). This common horn-shaped excrescence (see Figure 20.25), arising from keratinocytes, may resemble a viral wart clinically. The histology should be checked to distinguish benign and malignant lesions, as both have been known to arise from similar appearing lesions. Excision, or curettage with cautery to the base, is the treatment of choice. This is a common benign epidermal tumour, unrelated to sebaceous glands, found in older individuals. The term ‘senile wart’ should be avoided as it offends many patients. Usually unexplained but: Seborrhoeic keratoses usually arise after the age of 50 years, but flat inconspicuous lesions are often visible earlier. They are often multiple (Figures 20.4 and 20.5) but may be single. Lesions are most common on the face and trunk. The sexes are equally affected. Figure 20.4 Typical multiple seborrhoeic warts on the shoulder. Each individual lesion might look worryingly like a malignant melanoma but, in the numbers seen here, the lesions must be benign. Figure 20.5 Numerous unsightly seborrhoeic warts of the face. Physical signs: Lesions may multiply with age but remain benign. Seborrhoeic keratoses are easily recognized. Occasionally, they can be confused with a pigmented cellular naevus, a pigmented basal cell carcinoma or, most importantly, a malignant melanoma. Dermatosis papulosa nigra (Figures 14.3 and 20.6) is a long-winded name for a common variant of seborrhoeic keratoses affecting black adults. Multiple pigmented papules, just raised or filiform, appear on the face and neck but may extend to the trunk. The lesions may be unsightly and catch on jewellery. Histologically they are like seborrhoeic warts. The condition may run in families, being inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Figure 20.6 Dermatosis papulosa nigra. Stucco keratoses are another variant of seborrhoeic keratoses and are seen most often around the ankles after the age of 50. They have a similar ‘stuck on’ appearance to seborrhoeic warts and are small (1–2 mm) white keratotic papules that are easily lifted off the skin with a finger nail, without bleeding. Biopsy is needed only in rare dubious cases. The histology is diagnostic (Figure 20.7): the lesion lies above the general level of the surrounding epidermis and consists of proliferating basal cells and horn cysts. Stucco keratoses have a slightly different histology with loose lamellated hyperkeratosis overlying regular papillomatosis Figure 20.7 Histology of a seborrhoeic keratosis. Seborrhoeic keratoses can safely be left alone, but ugly or easily traumatized ones can be removed with a curette under local anaesthetic (this has the advantage of providing histology) or by cryotherapy. If treatment is requested for dermatosis papulosa nigra, gentle electrodessication or snipping of a few trial lesions initially is the best approach. Cryotherapy should be avoided for dermatosis papulosa nigra, as hypo or hyperpigmentation may result. These common benign outgrowths of skin affect mainly the middle-aged and elderly. This is unknown but the trait is sometimes familial. Skin tags are most common in obese women, and rarely are associated with tuberous sclerosis (p. 345), acanthosis nigricans (p. 311) or acromegaly and diabetes. Skin tags are soft skin-coloured or pigmented pedunculated papules commonly found around the neck and within the major flexures (Figure 20.8). They look unsightly and may catch on clothing and jewellery. Figure 20.8 Numerous axillary skin tags. The appearance is unmistakable. Tags are rarely confused with small melanocytic naevi. Small lesions can be snipped off with fine scissors, frozen with liquid nitrogen or destroyed with a hyfrecator without local anaesthesia. There is no way of preventing new ones from developing. The term naevus refers to a skin lesion that has a localized excess of one or more types of cell in a normal cell site. It is the name used for a cutaneous hamartoma. Histologically, the cells are identical to or closely resemble normal cells. Naevi may be composed mostly of keratinocytes (e.g. in epidermal naevi), melanocytes (e.g. in congenital melanocytic naevi), connective tissue elements (e.g. in connective tissue naevi; p. 346) and a mixture of epithelial and connective tissue elements (e.g. in sebaceous naevi). In this context such naevi are hamartomas or malformations. This lesion is an example of cutaneous mosaicism (p. 343) and so tends to follow Blaschko’s lines (Figure 20.9). Keratinocytes in these lines of wart-like growth are genetically different from their normal appearing neighbours. Keratolytics (Formulary 1, p. 401) lessen the roughness of some and small epidermal naevi may be excised. Alternatively, a trial area may be destroyed with a carbon dioxide laser and the subsequent scar assessed before extending treatment (p. 380). Figure 20.9 Linear warty epidermal naevus. Melanocytic naevi (moles) are localized benign tumours of melanocytes. Their classification (Table 20.2) is based on the site of the aggregations of the abnormal melanocytes (Figure 20.10). Figure 20.10 Types of acquired melanocytic naevi. Table 20.2 Classification of melanocytic naevi. The cause is unknown. A genetic factor is likely in many families, along with excessive sun exposure during childhood. With the exception of congenital melanocytic naevi (p. 283), most appear in early childhood, often with a sharp increase in numbers during adolescence and after severe sunburn. Further crops may appear during pregnancy, oestrogen therapy, flare-ups of lupus erythematosus or, rarely, after cytotoxic chemotherapy and immunosuppression. New melanocytic naevi appear less often after the age of 20 years. Melanocytic naevi in childhood are usually of the ‘junctional’ type, with proliferating melanocytes in clumps at the dermo-epidermal junction. Later, the melanocytes round off and ‘drop’ into the dermis. A ‘compound’ naevus has both dermal and junctional components. With maturation, the junctional component disappears so that the melanocytes in an ‘intradermal’ naevus are all in the dermis (Figure 20.10). Figure 20.11 Congenital melanocytic naevus. Figure 20.12 A large hairy congenital melanocytic naevus. (Dr Auf Qaba, St John’s Hospital, Livingstone. Reproduced with permission of Dr Auf Qaba.) These are present at birth or appear in the neonatal period and are seldom less than 1 cm in diameter. Their colour varies from brown to black or blue–black. With maturity some become protuberant and hairy, with a cerebriform surface. Such lesions can be disfiguring (e.g. a ‘bathing trunk’ naevus). Congenital melanocytic naevi carry an increased risk of malignant transformation, depending on their size. Giant congenital naevi with a diameter greater than 20 cm have a substantial risk of developing melanoma (lifetime risk up to 5–7%). On the other hand, small-sized congential naevi (less than 1.5 cm) and medium-sized (1.5–20 cm) have a low risk of melanoma. This risk of developing melanoma appears to be maximum in childhood and adolescence. In contrast to common acquired naevi, which are confined to the superfiical dermis, congenital naevi often extend deeply into the subcutaneous fat. The finding of a giant congenital melanocytic naevus in a posterior midline location associated with multiple satellite naevi should prompt a consultation with a neurologist and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to rule out neurocutaneous melanosis. Figure 20.13 Junctional melanocytic naevus. These are roughly circular macules. Their colour ranges from mid to dark brown and may vary even within a single lesion. Most melanocytic naevi of the palms, soles, mucous membranes and genitals are of this type. Figure 20.14 Compound melanocytic naevus. No recent change. These are domed pigmented nodules of up to 1 cm in diameter. They arise from junctional naevi as melanocytes ‘drop off’ from the epidermis to form collections of cells in the dermis. They may be light or dark brown but their colour is more even than that of junctional naevi. Most are smooth, but larger ones may be cerebriform, or even hyperkeratotic and papillomatous; many bear hairs. Figure 20.15 Intradermal melanocytic naevus with numerous shaved hairs. These look like compound naevi but are less pigmented and often skin-coloured. Figure 20.16 Spitz naevus. These are seen most often in children. They develop over a month or two as solitary pink or red nodules of up to 1 cm in diameter and are most common on the face and legs. Although benign, they are often excised because of their rapid growth. Figure 20.17 The blue ink matches the blue naevus. So-called because of their striking slate grey–blue colour, blue naevi usually appear in childhood and adolescence, on the limbs, buttocks and lower back. They are usually solitary. Histologically, nests of heavily pigmented melanocytes are found deep in the dermis, which gives the characteristic blue colour as a result of the Tyndall effect. Pigment in dermal melanocytes is responsible for these bruise-like greyish areas seen on the lumbosacral area of most Down’s syndrome and many Asian and black babies. They usually fade during childhood. Figure 20.18 Atypical moles in a 12-year-old girl. Note the malignant melanoma lying between the scapulae. Clinically atypical melanocytic naevi can occur sporadically or run in families as an autosomal dominant trait, with incomplete penetrance, affecting several generations. Some families with atypical naevi are melanoma-prone and in 20% of these mutations in the cell cycle regulating gene CDKN2A on chromosome 9p21 are found. These patients have greater than 50 large irregularly pigmented naevi, commonly on the trunk but some may be present on the scalp. Their edges are irregular and they vary greatly in size – many being over 1 cm in diameter. Some are pinkish and an inflamed halo may surround them. Some have a mamillated surface. Patients with multiple atypical melanocytic or dysplastic naevi with a positive family history of malignant melanoma should be followed up 6-monthly for life. Total body photography can often be helpful to monitor changes in atypical naevi. Melanomas develop in almost all patients with atypical mole syndrome who have both a parent and sibling with the syndrome and a history of melanoma. This is the most important part of the differential diagnosis. Melanomas are very rare before puberty, single and more variably pigmented and irregularly shaped (other features are listed below under Complications). These can cause confusion in adults but have a stuck-on appearance and are warty. Tell-tale keratin plugs and horny cysts may be seen with the help of a lens or dermatoscope. These may be found on any part of the skin and mucous membranes. More profuse than junctional naevi, they are usually grey–brown rather than black, and develop more often after adolescence. These are tan macules less than 5 mm in diameter. They are confined to sun-exposed areas, being most common in blond or red-haired people. Benign proliferations of blood vessels, including haemangiomas and pyogenic granulomas, may be confused with a vascular Spitz naevus or an amelanotic melanoma. Dermoscopy is most helpful in distinguishing from a naevus or melanoma (Chapter 28). Most acquired lesions fit into the scheme given in Figure 20.10: orderly nests of abnormal melanocytes are seen in the junctional region, in the dermis, or in both. However, some types of melanocytic naevi have their own distinguishing features. In congenital naevi the abnormal melanocytes may extend to the subcutaneous fat, and hyperplasia of other skin components (e.g. hair follicles) may be seen. A Spitz naevus has a histology worryingly similar to that of a melanoma. It shows dermal oedema and dilatated capillaries, and is composed of large epithelioid and spindle-shaped melanocytes, some of which may be in mitosis. In a blue naevus, the abnormal melanocytes are seen in the mid and deep dermis. The main features of clinically atypical (dysplastic) naevi are lengthening and bridging of rete ridges, and the presence of junctional nests showing melanocytic dysplasia (nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromatism). Fibrosis of the papillary dermis and a lymphocytic inflammatory response are also seen. Pain and swelling are common but are not features of malignant transformation. They are caused by trauma, bacterial folliculitis or a foreign body reaction to hair after shaving or plucking. Figure 20.19 Halo naevus. So-called ‘halo naevi’ are uncommon but benign. There may be vitiligo elsewhere. The naevus in the centre often involutes spontaneously before the halo repigments. This is extremely rare except in congenital melanocytic naevi, where the risk has been estimated at 0.5–10%, depending on their size (Figure 20.20), and in the atypical naevi of melanoma-prone families. It should be considered if the following changes occur in a melanocytic naevus: Figure 20.20 Malignant melanoma developing within a congenital melanocytic naevus. If changing lesions are examined carefully, remembering the ‘ABCDE’ features of malignant melanoma (Table 20.3), few malignant melanomas will be missed. Table 20.3 The ABCDE of malignant melanoma. Excision is needed when: Figure 20.21 Sebaceous naevus of the scalp. A flat hairless area at birth, usually in the scalp, these naevi become more yellow and raised at puberty. Secondary benign neoplasms (trichoblastoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum) can arise over time within a naevus sebaceus. Rarely, malignant transformation into a basal cell carcinoma can occur in adult life. Often incorrectly called sebaceous cysts, these are common and can occur on the scalp, face, behind the ears and on the trunk. They often have a central punctum; when they rupture, or are squeezed, foul-smelling cheesy material comes out. Histologically, the lining of a cyst resembles normal epidermis (an epidermoid cyst) or the outer root sheath of the hair follicle (a pilar cyst). Occasionally, an adjacent foreign body reaction is noted. Treatment is by excision, or by incision followed by expression of the contents and removal of the cyst wall. Failure to remove the entire cyst wall may result in recurrence. Milia are small subepidermal keratin cysts (Figure 20.22). They are common on the face in all age groups and appear as tiny white millet seed-like papules of 0.5–2 mm in diameter. They are occasionally seen at the site of a previous subepidermal blister (e.g. in epidermolysis bullosa and porphyria cutanea tarda). The contents of milia can be picked out with a sterile needle or pointed scalpal blade (No. 11) without local anaesthesia. Figure 20.22 Milia. Figure 20.23 Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis. The inflammation of the underlying cartilage is painful enough to wake up patients repeatedly at night. This terminological mouthful is, strictly, not a neoplasm, but a chronic inflammation. A painful nodule develops on the helix or antehelix of the ear, most often in men. It looks like a small corn, is tender and prevents sleep if that side of the head touches the pillow. Histologically, a thickened epidermis overlies inflamed cartilage. It may be caused by prolonged excess pressure on the skin overlying the cartilage. A pressure-relieving pillow may help. Wedge resection under local anaesthetic is effective if cryotherapy or intralesional triamcinolone injection fails. These discrete rough-surfaced lesions crop up on sun-damaged skin. They are best cosidered as premalignant. Pathologically there is a case for classifying them as squamous cell carcinomas in situ but very few progress to invasive squamous cell carcinomas. The effects of sun exposure are cumulative. Those with fair complexions living near the equator are most at risk and invariably develop these ‘sun warts’. A recent UK survey showed that one-third of men over 70 years had actinic keratoses. Melanin protects, and actinic keratoses are not seen in black skin. Conversely, albinos are especially prone to develop them. They affect the middle-aged and elderly in temperate climates, but younger people in the tropics. The pink or grey rough scaling macules or papules seldom exceed 1 cm in diameter (Figure 20.24). Their rough surface is sometimes better felt than seen. Figure 20.24 Typical rough-surfaced actinic keratoses on the scalp. Transition to an invasive squamous cell carcinoma, although rare, should be suspected if a lesion enlarges, becomes nodular, ulcerates or bleeds. Luckily, such tumours seldom metastasize. A cutaneous horn is a hard keratotic protrusion based on an actinic keratosis, a squamous cell papilloma or a viral wart (Figure 20.25). Figure 20.25 Cutaneous horn with a bulbous fleshy base. There is usually no difficulty in telling an actinic keratosis from a seborrhoeic wart, a viral wart (p. 227), a keratoacanthoma, an intraepidermal carcinoma or an invasive squamous cell carcinoma. A biopsy is needed if there is concern over invasive change. Alternating zones of hyper- and parakeratosis overlie a thickened or atrophic epidermis. The normal maturation pattern of the epidermis may be lost and occasional pleomorphic keratinocytes may be seen. Solar elastosis is seen in the superficial dermis. Freezing with liquid nitrogen or carbon dioxide snow is simple and effective. Shave removal or curettage is best for large lesions and cutaneous horns. Multiple lesions, including subclinical ones, can be treated with 5-fluorouracil cream (Formulary 1, p. 408) after specialist advice. The cream is applied once or twice daily until there is a marked inflammatory response in the treated area. This takes about 3 weeks and only then should the applications be stopped. Healing is rapid. Most patients dislike the pain and appearance of their faces during treatment but are pleased with their ‘new’ smooth skin afterwards. Severe discomfort from the treatment may be alleviated by the short-term application of a local steroid. 5-Fluorouracil cream is more effective for keratoses on the face than on the arms. Alternatively, less effective but causing less inflammation, 5-fluorouracil cream can be applied on just 1–2 days a week for 8 weeks. Multiple actinic keratoses can also be treated with imiquimod, a modulator of innate immunity (Formulary 1, p. 408). It activates Toll-like receptor 7 causing an immune reaction that destroys abnormal cells. Applied as a cream two to three times weekly for up to 16 weeks, the response is similar to that following 5-fluorouracil, described above. 3% Sodium diclofenac made up in a hyaluronan gel creates less havoc but also lower cure rates. Recently, ingenol mebutate gel was approved in the United States for actinic keratoses as a 2–3 day course. Photodynamic therapy (p. 376), using aminolaevulinic acid hydrochloride followed by blue light, is effective but requires specialist facilities. Lesions that do not respond should be regarded with suspicion, and biopsied. This is the most common form of skin cancer. It crops up most commonly on the faces of the middle-aged or elderly. Neglected lesions can invade and cause significant local destruction but, for practical purposes, never metastasize. Basal cell was first described in 1824 as a rodent ulcer. Most patients often describe a spontaneous non-healing sore that may bleed and scab. Prolonged sun exposure is the main factor so these tumours are most common in fair skinned individuals who have lived in sunny areas, high altitudes or near the equator. They may also occur in scars caused by radiation exposure, vaccination or trauma. Photosensitizing pitch, tar and oils can act as cocarcinogens with ultraviolet radiation. Previous treatment with arsenic, once present in many ‘tonics’, predisposes to multiple basal cell carcinomas, often after a lag of many years. Multiple basal cell carcinomas are found in the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin’s syndrome) where they may be associated with palmoplantar pits, jaw cysts and abnormalities of the skull, vertebrae and ribs. The syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and is caused by a mutation of the Patched (PTCH) gene, involved in embryonic tissue growth and organization. Other genetic conditions such as xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism and Bazex syndrome are also associated with the development of multiple basal cell carcinomas. This is the most common type. An early lesion is a small glistening translucent, sometimes umbilicated, skin-coloured papule that slowly enlarges. Central necrosis, although not invariable, leaves an ulcer with an adherent crust and a rolled pearly edge (Figure 20.26). Coarse telangiectatic vessels often run across the tumour’s surface (Figure 20.27). Without treatment such lesions may reach 1–2 cm in diameter in 5–10 years. Figure 20.26 Early basal cell carcinoma with rolled opalescent edge and central crusting. Figure 20.27 Basal cell carcinoma with marked telangiectasia and ulceration.

Skin Tumours

Derived from

Benign

Premalignant/carcinoma in situ

Malignant

Epidermis and appendages

Viral wart

Cutaneous horn

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Skin tag

Linear epidermal naevus

Melanocytic naevus

Sebaceous naevus

Epidermal/pilar cyst

Milium

Chondrodermatitis

Nodularis helicis

Actinic keratosis

Basal cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Malignant melanoma

Paget’s disease of the nipple (although, strictly, a breast tumour)

Dermis

Haemangioma

Lymphangioma

Glomus tumour

Pyogenic granuloma

Dermatofibroma

Neurofibroma

Neuroma

Keloid

Lipoma

Lymphocytoma cutis

Mastocytosis

Kaposi’s sarcoma

Lymphoma

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Merkel cell carcinoma

Metastases

Prevention

Tumours of the epidermis and its appendages

Benign

Viral warts

Cutaneous horn

Seborrhoeic keratosis (basal cell papilloma, seborrhoeic wart)

Cause

Presentation

Clinical course

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Treatment

Skin tags (acrochordon)

Cause

Presentation and clinical course

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Naevi

Linear epidermal naevus

Melanocytic naevi

Congenital melanocytic naevi

Acquired melanocytic naevi

Junctional naevus

Compound naevus

Intradermal naevus

Spitz naevus

Blue naevus

Atypical melanocytic naevus

Cause and evolution

Presentation

Congenital melanocytic naevi (Figures 20.11 and 20.12).

Junctional melanocytic naevi (Figure 20.13).

Compound melanocytic naevi (Figure 20.14).

Intradermal melanocytic naevi (Figure 20.15).

Spitz naevi (in the past misleadingly called juvenile melanomas; Figure 20.16).

Blue naevi (Figure 20.17).

Mongolian spots (Figure 15.1).

Atypical naevus/mole syndrome (dysplastic naevus syndrome; Figure 20.18).

Differential diagnosis of melanocytic naevi

Malignant melanomas.

Seborrhoeic keratoses.

Lentigines.

Ephelides (freckles).

Haemangiomas.

Histology

Complications

Inflammation.

Depigmented halo (Figure 20.19).

Malignant change.

Asymmetry

Border irregularity

Colour variability

Diameter greater than 0.5 cm

Evolution (change)

Treatment

Naevus sebaceus (Figure 20.21)

Epidermoid and pilar cysts

Milia

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (painful nodule of the ear, ear corn) (Figure 20.23)

Premalignant tumours

Actinic keratoses

Cause

Presentation

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

Histology

Treatment

Malignant epidermal tumours

Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer)

Cause

Presentation

Nodular.

Cystic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree