Skin Signs of Physical Abuse: Introduction

|

Child Abuse

Child abuse is an uncomfortable topic for most practitioners and is a source of anxiety, anger, and confusion among those who care for children. True incidence statistics are difficult to determine, but each year in the United States, of the approximately three million children referred to child protective services, approximately one million are determined to be the victims of abuse and neglect (or about 12 cases per 1,000 children) and approximately 1,500 die from abuse or neglect.1 Clearly, those whose practices involve the dermatologic care of children encounter real or suspected child abuse. Practitioners must have some basic knowledge of abuse and its evaluation to appropriately manage these cases.

Because many forms of physical abuse have external manifestations, the skin examination may serve as the first clue that abuse is taking place. Conversely, a broad knowledge of skin diseases provides a unique insight into those diagnoses that may mimic various forms of child abuse (Tables 106-1 and 106-2). The literature is rich in examples in which an astute clinician averted the disastrous results of a false claim of abuse by correctly diagnosing a dermatologic condition.

|

|

True abuse must be reported and a thorough evaluation conducted. It is essential that practitioners develop a relationship with the institution or individual in their area who is best able to manage these difficult cases. Ideally there should be an abuse team consisting of a dermatologist, pediatrician, social worker, medical photographer, and, when needed, pediatric subspecialists such as orthopedists, hematologists, psychologists, and gynecologists. The need for specialization in this field is highlighted by the institution in the United States of pediatric subspecialty board certification in child abuse, beginning in 2010. It is most helpful if one’s relationship is forged with the abuse team before an abuse incident and a set protocol for dealing with alleged or suspected abuse is established in the practitioner’s office. Local emergency phone numbers for reporting abuse can be obtained from the Child Welfare Information Gateway or Childhelp National Headquarters (Table 106-3).

|

Child abuse spans all ages with 32% of abused children being younger that 4 years of age, 24% being 4–7 years of age, and 19% being 8–11 years of age. Typical children who suffer abuse have emotional or behavioral problems, have special medical needs, have several siblings, live in single-parent households, or live at or below the poverty level. Abuse is approximately two times more common in Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Native Alaskans, and African American children compared to the average American population. Perpetrators tend to have emotional or psychological problems, have frequently been victims of abuse themselves, abuse drugs or alcohol, are perpetrators of spousal abuse or have a history of marital discord, have marginal parental skills or knowledge, and have poor self-esteem. Parents are the perpetrator 80% of the time.2 Although these profiles are helpful, it is important to remember that any child may be the victim of abuse.

Bruising is the result of blunt trauma, delivered either accidentally or intentionally. Active children, particularly toddlers, are prone to multiple bruises, and the identification of abusive injury is fraught with difficulty. The size, shape, color, and feel of a bruise varies on the basis of anatomic site, the degree of force used, the firmness of the object delivering the force, and the underlying health of the injured individual. Great care and attention to detail must be exercised when evaluating these children who likely have been brought to the office for some other complaint. The history should include as much detail as possible and inconsistencies in the parent’s story clearly documented in the medical record (eTable 106-3.1).3 It is essential to perform a total body, skin, and mucous membrane examination. It is also important to note the child’s behavior and parent–child interactions.

|

The color of all bruises should be noted and clearly documented. This may aid in determining the age of a bruise and may point out inconsistencies in the caretaker’s history. Multiple bruises of differing colors may indicate ongoing trauma rather than one isolated incident. Caution must be exercised in dogmatically, stating the time of injury based on bruise characteristics because color depends on the intensity, depth, and location of the injury. There is good evidence that a bruise with any yellow color must be older than 18 hours, but a bruise may be red, blue, or purple/black throughout its life span, from beginning to resolution. Bruises of identical age and cause on the same person may not appear as the same color and may not change at the same rate.4 It is most prudent to document color without alluding to a specific age of a bruise in the medical record. Faint bruised might be more easily visualized with the use of a Wood’s lamp.

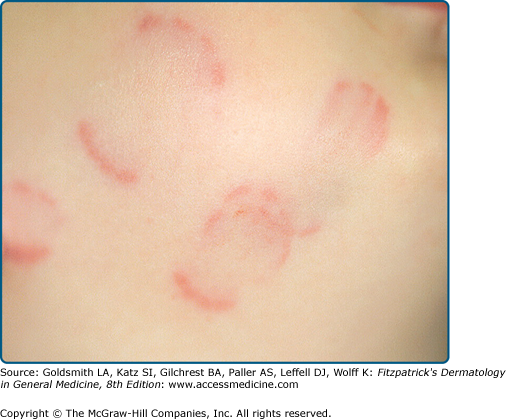

Although there are no absolute differentiating features, certain aspects of an intentionally inflicted bruise may suggest abuse. Because young children tend to explore in a forward direction, accidents are more frequent on the distal arms and legs, knees, elbows, and forehead. Soft, padded, posterior, and protected areas of the body are far less likely to be accidentally injured. Bruises on the abdomen, buttocks (Fig. 106-1), thighs, genitalia, ear lobes, and cheeks are uncommon, so marks in these areas should raise concern.

Inflicted bruises often leave patterned imprints of a hand, whip, or hard object. Linear purpura, with a small triangle at the base (Fig. 106-2) representing the interdigital and finger web spaces, occurs after a slap injury. Grab or pinch marks can be recognized by their location on soft padded areas and their unusual patterning. Circumferential purpura or hemosiderin pigmentation (Fig. 106-3) suggests a ligature injury, which would be difficult to explain as accidental. Bite marks (Fig. 106-4) are always inflicted, although they are sometimes from siblings or other children. The shape and size of the marks can identify an adult mouth versus a bite from a child. It is helpful to include a ruled measuring scale in any photographs to help forensic identification at a later date.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree