Skin Problems in Amputees: Introduction

|

Technical Background: Limb Prostheses

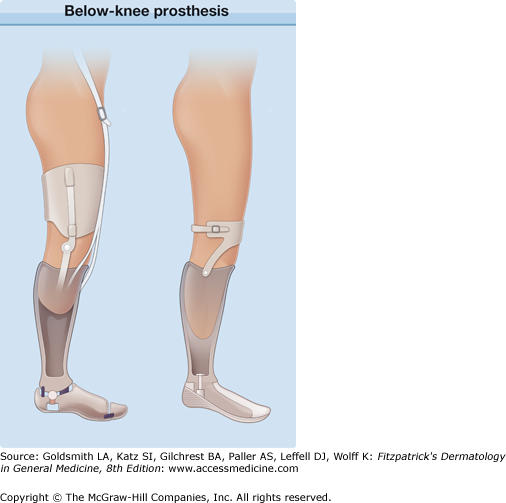

In most centers, artificial limbs are constructed in a modular fashion.1 The stump is placed in a thermoplastic socket that is then fitted into the main body of the limb. The bulk of the prosthesis comprises a metal frame with articulations and an outer casing of acrylic resin or carbon composite material. Before fitting the limb, many patients place their stump in a liner designed to reduce friction on the skin. This may be an expanded plastic cup, a silicon/mineral oil sleeve, or a cotton or nylon sock. The prosthetic limb, once fitted, is held in position by one of a range of suspension elements. In above-knee (Fig. 96-1) or proximal arm amputations, this is usually a fabric belt arrangement worn around the waist or shoulders, respectively. Below-knee amputees require a different system using either a butyl rubber sleeve or corset to hold the appliance firmly onto the thigh (Fig. 96-2). Many patients with above-knee amputations now use a suction socket device that provides sufficient suspension by holding the prosthesis in place through negative pressure without the need for additional belts (see Fig. 96-1).

Limb prostheses are the subject of continual technological development particularly in the field of bionics. Myoelectric devices, for example, rely on skin contact with electrodes to detect neuromuscular signals that can be converted to artificial limb movement. Neuroprosthetic devices involve implantation of electrodes into neural tissue usually through the skin, for example, cochlear implants. Such devices are under development for prosthetic limbs. These devices thus have the potential for causing skin problems.

Dermatologic Problems in Amputees

The skin of an amputation stump is not designed to withstand the physical insults it encounters within a prosthetic limb. For example, although some adaptation to friction or pressure occurs, some skin problems are inevitable. If these dermatoses cannot be prevented or rapidly resolved by prosthesis adjustment or medical intervention, they can incapacitate the patient, particularly those who have lower limb, weight-bearing prostheses. As a result, patients may suffer social isolation, emotional distress, or even financial deprivation if they are unable to work.

Skin problems may occur because of allergy or chemical irritation to materials in contact with the skin, as well as from trauma and occlusion. Examples of physical stresses on the skin include shearing and friction from elements in the socket and pressure on load-bearing areas, especially on the tibial tuberosity in below-knee amputations and the ischial tuberosity, adductor region, or groin in above-knee amputations. In all cases, the occlusion results in increased humidity from trapped perspiration, increasing the likelihood of irritation, allergy, and infection.

The common skin disorders in amputation stumps can be classified into diseases related to the reasons for the amputation, physical effects of a prosthesis, infection, contact dermatitis, and other cutaneous disorders.

The great majority of artificial limb wearers are amputees, although a small proportion are people with congenital limb malformations. Lower limb amputees are the most numerous and are also the group at greatest risk of skin problems. Traumatic amputations are possibly more likely to be associated with a dermatosis2 although the commonest problems encountered are the same as for all amputees.3 Modern limb prostheses allow many of today’s amputees to lead an active life with good mobility. Nevertheless, as many as 73% of one cohort of lower limb amputees reported at least one skin disorder.2 In a further group of 745 lower leg amputees, 40.7% had at least one skin problem. Further analysis identified four factors independently associated with dermatologic disorders, namely transtibial amputation, employment status, type of walking aid used, and peripheral vascular disease.4 A more recent questionnaire-based study of 805 lower limb amputees5 suggests that the factors more likely to be associated with skin problems are, smoking, younger age, female sex, washing the stump frequently and the use of antibacterial soaps. Overall one-third of amputees, either upper or lower limb, experiences a skin problem that significantly interferes with the normal use of the artificial limb.6

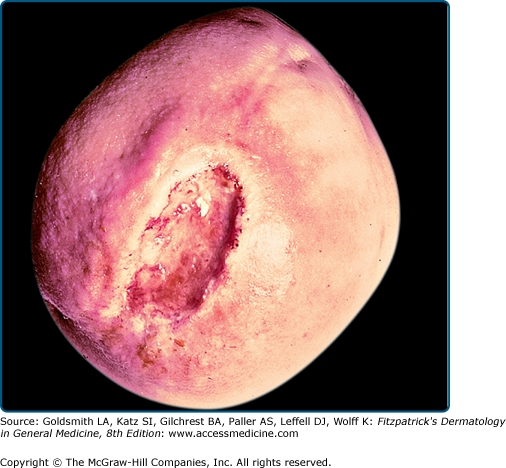

Several disorders resulting in the need for amputation can have a significant impact on skin integrity. In general, younger patients require artificial limbs because of traumatic amputations, congenital abnormalities, or malignancy, whereas in the older age group, arterial disease and vascular complications of diabetes mellitus predominate. Amputations after trauma or severe vasculitis may be associated with scarring that makes for a suboptimal prosthesis fit (Fig. 96-3). Stump dermatoses appear to be more likely in patients following traumatic amputations. Koc et al2 found a skin problem in nearly three quarters of amputees most of whom had lost a limb as a consequence of mine explosions. The nature of current conflicts means that, presently, such amputations are unfortunately common amongst both service personnel and civilians. Vasculitis resulting in amputation may be ongoing and cause problems in the skin of amputation stumps (Fig. 96-4). However, it is diabetes mellitus that is particularly associated with protracted skin problems (Chapter 151) as a result of impaired wound healing, susceptibility to infection, abnormal sensory nerve function, and disruption of normal tissue fluid balance.7 Diabetic amputees as a group require more frequent clinical review to prevent complications. Treatment of the diabetic amputee not only requires good control of the blood glucose level but possibly a change of the stump environment through adjustment or redesign of the artificial limb. The diabetic amputee highlights the need for close links with a prosthetics department, which allow rapid referral of patients for assessment.

The physical effects of wearing a prosthesis are the most common causes of skin problems.6,8 These can be divided into those resulting from repeated direct trauma and those secondary to disturbance of tissue fluid dynamics.

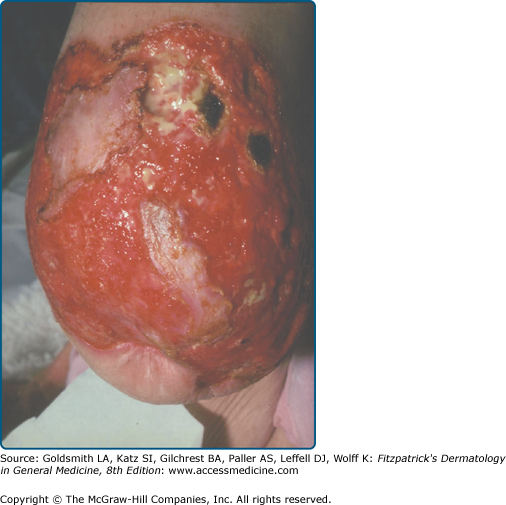

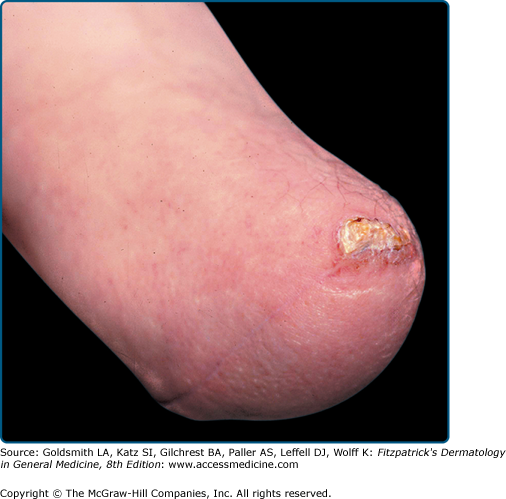

Ulceration and callus formation are seen where there is chronic pressure or repeated frictional forces on stump skin. Ulceration may also be caused by infection or poor cutaneous nutrition, particularly secondary to diabetes mellitus (Figs. 96-5 and 96-6). Stump ulcers should be treated early as malignancy may develop in long-standing ulceration.9 With repeated infection and ulceration, an amputation scar on the distal stump skin can erode further. In some cases, the skin may become completely adherent to bone and develop thick, callus-like hyperkeratosis (Fig. 96-7), which may necessitate revision of the distal bony surface. Ulceration or other injuries incurred while putting on artificial limb components may be particularly associated with poor manual dexterity consequent on neurological disorders or arthritic changes.10,11 Incorrect use of some appliance components can also result in injury.12 Patient selection and access to follow-up advice is therefore important in reducing such injuries. Apparently spontaneous ulceration at unexpected sites is occasionally seen (Fig. 96-8). In every instance, the cause of the ulceration must be determined to resolve a chronic process that can become totally disabling. However, a recent study examining 102 patients over 4 years suggests that the majority of patients with delayed wound healing or secondary ulcers will experience healing despite continuing to use their prosthesis, provided they are carefully monitored.13

In some patients, eczema may be caused by a poorly fitted or misaligned prosthesis or by edema and congestion of the terminal portion of the stump; only with alleviation of these problems does the condition clear.

Epidermoid cysts and follicular keratoses are two ends of a spectrum of the same disorder. Repeated pressure and friction from the prosthesis appears to cause invagination of keratin around hair follicles, which then results in a foreign-body reaction. Follicular keratoses are therefore the earliest changes.14 These are very common, often multiple, and distributed at sites of weight bearing such as the anterior tibial area, popliteal fossa, and the adductor or inguinal areas of the thigh (Fig. 96-9A). Fortunately, they cause little trouble in many cases, but they can become inflamed and painful particularly if the patient picks at them to extract the keratin plug or if they become infected. Inflamed follicular keratoses can have an acneiform appearance, leading some to suggest that they represent a form of acne mechanica. When the continued pressure and friction causes the keratin to extend deeper into the dermis, larger cystic lesions, 1–3 cm in diameter, form; these are commonly termed posttraumatic epidermoid cysts. Meulenbelt et al15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree