15 Skeletal augmentation

Synopsis

Facial skeletal augmentation can add angularity, definition, or balance to a face of normal dimensions.

Facial skeletal augmentation can add angularity, definition, or balance to a face of normal dimensions.

Given acceptable occlusion, implant surgery can be an alternative or an adjunct to orthognathic surgery in disproportioned faces.

Given acceptable occlusion, implant surgery can be an alternative or an adjunct to orthognathic surgery in disproportioned faces.

Most skeletal augmentation is done with alloplastic implants.

Most skeletal augmentation is done with alloplastic implants.

Solid silicone and porous polyethylene are the materials most commonly used for facial skeletal augmentation.

Solid silicone and porous polyethylene are the materials most commonly used for facial skeletal augmentation.

Incisions should be placed remote from implant placement.

Incisions should be placed remote from implant placement.

The subperiosteal plane is preferred for implant placement.

The subperiosteal plane is preferred for implant placement.

Gaps between the implant and the skeleton result in unanticipated increases in augmentation.

Gaps between the implant and the skeleton result in unanticipated increases in augmentation.

Screw fixation of the implant prevents gaps between the implant and the skeleton.

Screw fixation of the implant prevents gaps between the implant and the skeleton.

Screw fixation of the implant prevents implant movement.

Screw fixation of the implant prevents implant movement.

All faces are asymmetric. Facial asymmetries should be discussed with patients preoperatively.

All faces are asymmetric. Facial asymmetries should be discussed with patients preoperatively.

Introduction

• The size and shape of the facial skeleton are fundamental determinants of facial appearance.

• Small asymmetries in skeletal morphology can be noticeable.

• Small changes through surgical intervention can be powerful.

• Augmentation is the predominant means of aesthetic contouring of the facial skeleton in non-Asian populations.

• The use of autogenous bone as an onlay graft is conceptually appealing, but limited by the morbidity associated with its harvest and the unpredictability of the result.

• Most facial skeletal augmentation is performed with alloplastic implants.

Basic science/disease process

Recently, senescent changes in the facial skeleton have been investigated. Studies revealed retrusion of the midface and mandibular skeleton over time. This supports the concept of alloplastic augmentation of the facial skeleton as part of the algorithm for facial rejuvenation and enhancement.1

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Neoclassical canons and facial anthropometries

For the purposes of painting and sculpture, Renaissance scholars and artists formulated ideal proportions and relations of the head and face. These were largely based on classical Greek canons. Although usually referenced in texts discussing facial skeletal augmentation, neoclassical canons have a limited role in surgical evaluation and planning, because they are based on idealizations. When the dimensions of normal males and females were evaluated and compared to these artistic ideals, it was found that some theoretic proportions are never found, and others are one of many variations found in healthy normal people, or those determined more attractive than normal.2 The neoclassical canons do not allow for the facial dimensions that are known to differ with sex and age. Most of these canons of proportion (e.g., the width of the upper face is equal to five eye-widths) are interesting but hold for few individuals and cannot be obtained surgically or, if obtainable, only with extremely sophisticated craniofacial procedures. For these reasons, we have found it more useful to use the anthropometric measurements of normal individuals to guide our gestalt in the selection of implants for facial skeletal augmentation (see Ch. 16). Normal-dimensioned faces are intrinsically balanced. That is, the relations between the various areas of the face relate to one another in a way that is not distracting to the observer. By comparing a patient’s dimensions to the average, the surgeon has some objective basis as to what anatomic area may be amenable to augmentation, and by how much.

Patient selection

Alternative to orthognathic surgery

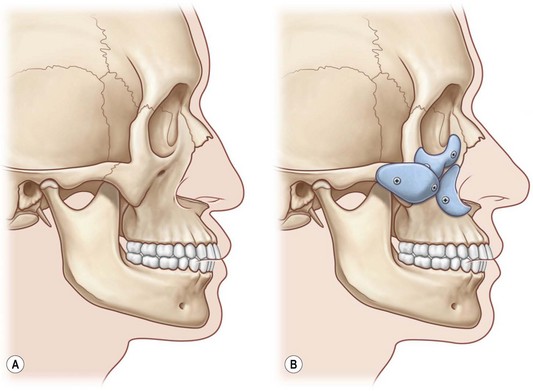

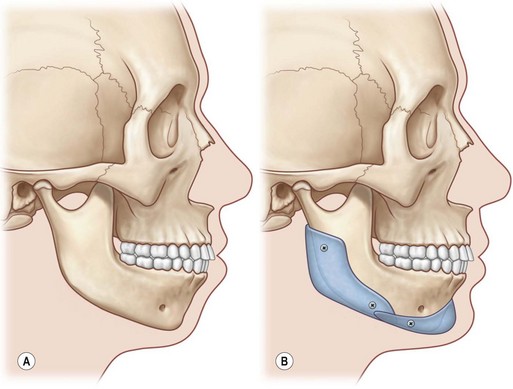

Midface and mandibular hypoplasia are common facial skeletal variants. In patients with these morphologies, occlusion is normal or has been compensated by orthodontics. These patients have neither respiratory nor ocular compromise. In skeletally deficient patients whose occlusion is normal or has been previously normalized by orthodontics, skeletal repositioning would necessitate additional orthodontic tooth movement. Such a treatment plan is time-consuming, costly, and potentially morbid. It is, therefore, appealing to few patients. In these patients, the appearance of skeletal osteotomies and rearrangements can be simulated through the use of facial implants. Diagrammatic representations of how implant surgery can mimic the appearance of skeletal osteotomies are shown in Figures 15.1 and 15.2.

Adjunct to orthognathic surgery

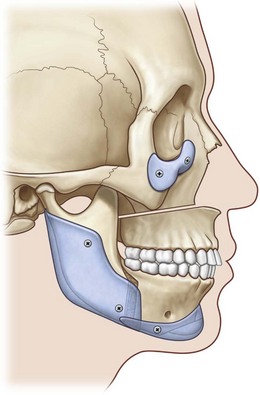

The LeFort I advancement may fulfill its functional role by creating appropriate occlusal relations but inadequately treats midface hypoplasia since only the lower half of the midface is advanced. This may result in a convexity confined to the lower half of the midface. Alloplastic augmentation of the infraorbital rim with or without malar implants can create a truly convex midface. Posterior mandible implants can camouflage osteotomy-induced irregularities along the mandibular border as well as malpositions of the mandibular angles. Chin implants can correct mandible border contour irregularities after sliding genioplasty (Fig. 15.3).

Rejuvenation

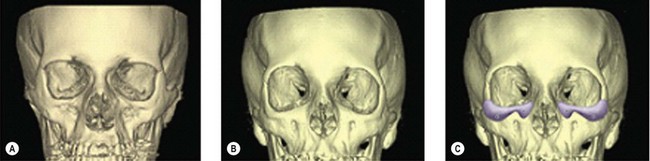

Traditional concepts of periorbital and midface aging and rejuvenation focus on the soft tissues. Recently, senescent changes in the supporting facial skeleton have been investigated. Findings in these studies revealed retrusion of the midface skeleton and mandible (Fig. 15.4). This diminution in projection would hasten the gravitational-induced descent of their overlying and now, less supported soft-tissue envelope.3 Alloplastic skeletal augmentation can both restore skeletal contours and support the overlying soft-tissue envelope.1

Treatment/surgical technique

Implant materials

Implant materials used for facial skeletal augmentation are biocompatible – that is, there is an acceptable reaction between the material and the host. In general, the host has little or no enzymatic ability to degrade the implant with the result that the implant tends to maintain its volume and shape. Likewise, the implant has a small and predictable effect on the host tissues that surround it. This type of relationship is an advantage over the use of autogenous bone or cartilage which, when revascularized, will be remodeled to varying degrees, thereby changing volume and shape. The alloplastic implants presently used for facial reconstruction have not been shown to have any toxic effects on the host.4 The host responds to these materials by forming a fibrous capsule around the implant, which is the body’s way of isolating the implant from the host. The most important implant characteristic that determines the nature of the encapsulation is the implant’s surface characteristics. Smooth implants result in the formation of smooth-walled capsules. Porous implants allow varying degrees of soft-tissue ingrowth that result in a less dense and less defined capsule. It is a clinical impression that porous implants, as a result of fibrous incorporation rather than encapsulation, have a lower tendency to erode underlying bone or migrate due to soft-tissue mechanical forces and, perhaps, are less susceptible to infection when challenged with an inoculum of bacteria. The most commonly used, commercially available materials today for facial skeletal augmentation are solid silicone, which has a smooth surface, and porous polyethylene.