■ In addition to the Stewart and modified Stewart, there are alternate options for a simple mastectomy. The placement and orientation of the incision must be based on the location of the biopsy scar and/or the location of the tumor. For a palpable tumor, particularly one close to the skin, the skin over the tumor should be included in the excised skin. Planning of the skin incision in conjunction with the plastic surgeon can be quite helpful in patients undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. If the patient has a surgical cancer biopsy incision, this scar should be resected with the underlying mastectomy specimen. Incisions located in proximity to the nipple–areolar complex can be resected within the central skin ellipse that is being sacrificed. Incisions that are located remote from the central nipple–areolar skin can sometimes be resected as a separate ellipse of sacrificed skin, as long as the remaining skin bridge is wide enough to remain viable. The original surgical cancer biopsy scars should not be left intact in the mastectomy skin flaps because of the oncologic concern that this skin may potentially harbor cancer cells (and the mastectomy skin is usually not being radiated, as is the case following lumpectomy); and from a wound healing perspective, the subcutaneous fat deep to the traumatized incisional skin will be less healthy and more likely to necrose. Old surgical biopsy scars that are unrelated to the cancer diagnosis can be left in place. Also, percutaneous needle biopsy scars can be left intact on the skin flaps, as these have not been shown to contribute to risk of local recurrence.

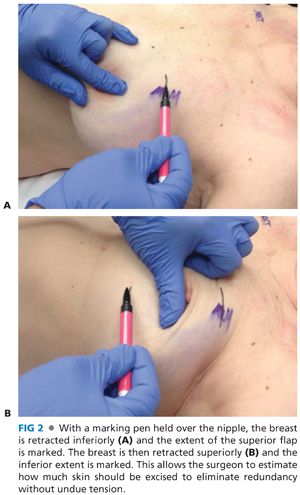

■ It is important to remove enough skin so that there is no redundancy but not so much that there is undue tension on the incision. A useful method to determine the placement of the superior and inferior incisions is to hold a marking pen in the air over the nipple and retract the breast inferiorly. Mark this site on the skin and then retract the breast superiorly to mark the inferior extent (FIG 2A,B).

■ When designing the ellipse, closure will be facilitated by making sure the superior and inferior incisions are of equal length (FIG 3). This can easily be assessed using a 3-0 silk suture.

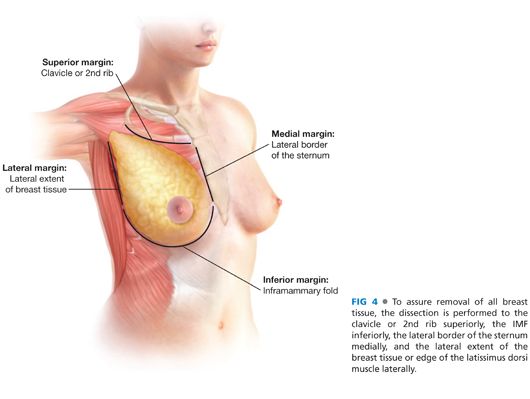

■ Before making the incision, mark the boundaries of the breast tissue. Although the breast is an obvious external feature of the human anatomy, its boundaries deep to the skin are less well defined. Lacking any clear-cut capsule to delineate breast tissue from surrounding fat and subcutaneous tissue, the surgeon must identify anatomic landmarks that serve as reasonable and relatively constant structures, beyond which it is unlikely to find significant amounts of breast tissue. These radial boundaries for the skin flaps essentially serve as a picture frame; and once these flaps are completed, the breast is dissected off the pectoralis major muscle en bloc with the pectoralis fascia. The conventionally accepted peripheral mastectomy flap boundaries are as follows: superior margin—clavicle or 2nd rib (identified by palpation); inferior margin—inframammary fold (IMF); medial margin—lateral border of the sternum (identified by palpation); lateral margin—the lateral extent of the breast tissue can be marked externally on the skin surface and the edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle is a useful vertical boundary that can be visually identified from within the mastectomy surgical field (FIG 4).

SKIN INCISION AND CREATION OF FLAPS

■ Once the skin incision has been mapped out on the breast, a scalpel is used to cut through the skin and dermis. Cautery is used to then obtain hemostasis. It is important to get into the right plane to raise flaps at the start. The initial incision should extend through full-thickness skin, just barely exposing the subcutaneous fat, and no further. Incising through deeper layers of subcutaneous fat will result in a splaying out of those fatty planes, and these deeper tissues will spuriously appear as anterior margin surfaces when analyzed and inked in the pathology laboratory. The actual anterior margin of the mastectomy specimen (beyond the central ellipse of sacrificed nipple–areolar skin) should be defined by the surgeon via dissection of the appropriate-thickness skin flaps. Failing to leave a small amount of tissue beneath the dermis can lead to ischemia and wound complications, and this can be particularly concerning in cases involving immediate reconstruction. Conversely, an excessively thick skin flap leaves the patient at risk for residual breast tissue on the chest wall, thereby increasing risk of local recurrence.

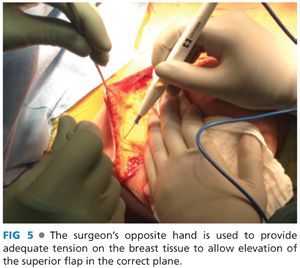

■ Starting with the superior flap, skin hooks are used to elevate the skin and provide appropriate tension for elevation of the flap (FIG 5). The key to elevating an appropriate flap is the tension on the breast tissue. Initially, a forceps can be used to get into the right plane; but once that plane is identified, traction with the contralateral hand of the surgeon using a laparotomy pad on the breast tissue will be critical. As the flap elevation proceeds, it is important to reposition the contralateral hand accordingly.

■ It is imperative that the assistant holding the skin hooks maintain retraction straight up (FIG 6). Often, a resident will retract toward themselves so they have a better view of the dissection. However, this can lead to exposing the dermis and possibly a buttonhole injury to the skin.

■ The correct plane will leave a small amount of subcutaneous fat beneath the dermis so that the blood supply is preserved while not leaving any breast tissue. This plane is often avascular (FIG 7). Intermittently inspecting and palpating the flap will assure the correct thickness. Older women (where much of the breast is fatty-replaced) and heavier patients often have a thicker flap of subcutaneous fat separating the skin from the underlying breast parenchyma. In contrast, younger and thin patients may have breast tissue closely abutting the dermis, allowing for a very narrow margin of error while raising the flap.

■ Flaps can be elevated using cautery, scissors, or a scalpel. Cautery will help provide hemostasis during the procedure. If sharp dissection is used, pressure on the breast with a laparotomy sponge will help maintain hemostasis.

■ The superior flap is complete when you reach the level of the clavicle. At this point, the pectoralis muscle should be identified and the pectoralis fascia divided (scored) along the length of the flap (FIG 8).

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree