CLINICAL IMPORTANCE

■ Improving outcomes: The sobering reality is that once patients with melanoma develop clinically apparent (palpable) nodal disease (advanced AJCC stage III), the risk of subsequent distant stage IV disease and recurrent lymph node basin disease, despite a complete therapeutic lymphadenectomy, is at least 50%6 and 15% to 50%,7 respectively. Therefore, the original motivation to study SLN biopsy was to establish an effective method of identifying and then treating lymph node disease early when microscopic, an approach termed “selective lymphadenectomy,” not to be confused with the aforementioned “sentinel lymphadenectomy,” which refers specifically to the SLN biopsy procedure. Such an approach would prevent the development of clinically palpable nodal disease and in turn improve the outcomes for the node-positive patients in terms of both regional disease control and survival. The collective experience with SLN biopsy demonstrates that these two goals have been accomplished.8,9

■ Staging and reducing morbidity: The stages I and II melanoma patient population represent at least 85% of the newly diagnosed patients. The prognosis of this group is very heterogeneous and dependent on a variety of primary tumor factors, specifically tumor thickness, ulceration, and mitotic rate, and probably most importantly, the presence of occult lymph node involvement.10 The role of SLN biopsy as a staging tool has been well established, as several published multivariable analyses demonstrate that the histologic status of the SLN is the strongest independent predictor of survival for stages I and II melanoma and therefore offers another motivation for SLN biopsy.10,11 The procedure is also intended to identify patients with pathologically node-negative disease for whom additional surgery is not indicated and adjuvant systemic therapy may not be of benefit, sparing these patients the morbidity of unnecessary surgery and treatment-related toxicities.

■ SLN biopsy is now accepted as a standard of care12,13 in the surgical management of appropriately selected melanoma patients. Central to the success of this minimally invasive approach, and in turn achieving the earlier described staging and treatment goals, is the consistent and accurate identification and complete removal of the SLN(s).

■ Although in simplest terms SLN biopsy is a straightforward surgical procedure, in reality, the overall approach integrates several necessary components: identification of the appropriate candidates, careful physical examination of the potential nodal basins at risk, preoperative assessment of the lymphatic drainage patterns, intraoperative localization and removal of all the SLN(s), and careful histologic assessment of the SLN(s).

IDENTIFYING THE APPROPRIATE CANDIDATES

■ Primary invasive cutaneous melanoma: The selection criteria for identifying the appropriate candidates for SLN biopsy is based on the predicted risk for the presence of microscopic lymph node involvement for those patients with newly diagnosed primary melanoma and clinically negative nodes. This is best determined by the various primary tumor factors inclusive of tumor thickness, ulceration,14 and mitotic rate, which define the five AJCC stages I and II substages of primary melanoma.10 The consensus recommendations are to offer SLN biopsy to any patient with a thickness of 1 mm or greater as long as they are safe operative candidates. SLN biopsy should also be strongly considered in any patient with a thickness of 0.7 to 0.99 mm, particularly if they have at least one of the following adverse prognostic features: Clark level IV or V, one mitotic figure or more per square millimeter, and lymphovascular invasion or microsatellites.12,15–17 For patients with a thickness of less than 0.76 mm, SLN can be considered if, based on other adverse risk factors, a risk of 8% to 10% of SLN involvement is anticipated. This, however, would be a minority of patients in this subset.14 Although these patients represent the vast majority who will be offered an SLN biopsy, a variety of other clinical scenarios are encountered with some frequency where SLN may also be considered. These scenarios are described in the 6 bulleted points that follow directly.

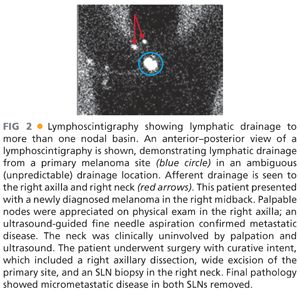

■ Primary melanoma in an ambiguous (unpredictable) lymphatic drainage site (i.e., head and neck or trunk location) and proven synchronous nodal involvement in at least one, but not all, of the potential regional lymph node basins at risk: These patients may be candidates for SLN biopsy to stage the other regional nodal basins proven to receive direct lymphatic drainage from the primary site but without clinical nodal involvement. Generally speaking, these patients will undergo treatment of the primary melanoma and the involved nodal basin with a wide excision and formal therapeutic lymphadenectomy in the same operative setting. In the event that preoperative lymphoscintigraphy (FIG 2) demonstrates lymphatic drainage to an additional but clinically negative regional nodal basin, SLN biopsy can also be performed at the same time in an attempt to be inclusive in the treatment of all nodal disease, both macro- and microscopic.

■ Mucosal melanoma: Patients with primary mucosal melanomas that are in locations with easy access for direct injection with the SLN localizing agents, conjunctival and anorectal in particular, can be candidates for SLN biopsy as part of their initial surgical management strategy. Although specific primary tumor criteria for these lesions are not well established for predicting the presence of occult regional node involvement, these tumors are most often diagnosed late and likely to have a high enough inherent risk to consider SLN biopsy.

■ True locally recurrent melanoma: Some patients develop recurrent melanoma at the edge of a previous wide excision site and may have one of the following three histologic features: in situ disease alone, in situ disease plus an invasive component, or invasive (dermal) component only. All three of these events are likely the result of an inadequate wide excision and an undetected positive margin and therefore represent a “true” local recurrence and have a good chance for long-term survival with surgical treatment. Most of these patients have clinically negative nodes, and in the context of a recurrent invasive component with the appropriate tumor characteristics (see earlier discussion), it is rational to offer these patients an SLN biopsy as a part of the definitive surgical therapy.

■ Limited satellite/in-transit metastases: In contrast to the patients with “true” locally recurrent disease, these patients represent manifestations of the biologic disease continuum of regional cutaneous metastases (stage III). Not infrequently, these patients will present with clinically negative regional lymph nodes, stage IIIb. If the extent of the regionally metastatic disease is limited (one or two lesions), a surgical approach to the recurrence is rational. The presence of synchronous microscopic nodal disease not only impacts disease stage, advancing to IIIc and therefore the prognosis, but also the treatment strategies. Therefore, SLN biopsy could also be used in this clinical scenario in conjunction with the resection of the recurrence(s).

■ After a wide excision: It is typical and preferable that the SLN biopsy be performed together in a single operative setting in conjunction with the definitive wide excision of the primary melanoma following a diagnostic incisional or excisional biopsy. Occasionally, a patient will have undergone a formal wide excision of the primary melanoma site and then be referred for consideration of an SLN biopsy. A theoretical concern is that the lymphatic drainage pattern of the skin brought together to close the surgical defect or surrounding a skin graft reconstruction has either been altered by the surgery or is far enough away from the original primary lesion that it may not accurately reflect that of the removed skin that was directly adjacent to the primary melanoma, resulting in the identification and removal of the wrong SLN(s). A few publications have put most of these concerns to rest. The data shows that although more afferent lymphatic vessels are likely to be accessed because of the broadened area injected, leading to more SLNs being removed and even the possibility of additional nodal basins explored in sites of ambiguous drainage (trunk and head and neck), the correct SLNs will likely be among the specimens removed, providing accurate nodal staging information.18 As long as complex rotational flaps were not used for the reconstruction, SLN can be recommended to patients when this clinical setting is encountered.

■ Prior surgery in a nodal basin: Occasionally, a primary melanoma will be diagnosed in a location with predicted or possible lymphatic drainage to a regional nodal basin in which surgical intervention has previously been performed, such as an SLN biopsy or lymph node dissection, as treatment for a previous melanoma or other malignancies. An SLN biopsy may still be possible, but a preoperative lymphoscintigraphy is mandated to determine how the lymphatic drainage has been affected or altered by the previous nodal surgery. Lymphatic drainage patterns may be demonstrated in one or more of the remaining nodes (if any exist) in the previously treated basin or diverted to another basin. This information is critical for appropriate surgical planning and operative positioning.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Pertinent information such as a prior personal history of melanoma or other malignancies and current or recent symptoms referable to the presence of metastatic disease should be elicited from the patient during the history.

■ Questions about allergic reactions to antibiotics, sulfa in particular, and intravenous (IV) contrast agents should be documented as this information may suggest an increased risk of an allergic reaction to the isosulfan blue dye and therefore may influence the decision to use a different blue dye such as methylene blue or not use any blue dye at all for the SLN procedure (see more details in the following text).

■ A thorough head-to-toe skin examination should be performed with the intent of identifying additional suspicious lesions that could represent another primary melanoma or other skin cancers. Diagnostic full-thickness punch or excisional biopsies should be performed on selected lesions.

■ Special attention should be paid to the region of the index melanoma. Visual inspection as well as palpation of the biopsy site and surrounding skin and soft tissues should be performed to determine the presence of any residual primary disease and/or satellite and in-transit metastases.

■ Skin and soft tissues between the primary lesion and draining lymph node basins should be palpated and closely examined for in-transit disease. All suspicious cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions may undergo fine needle aspiration for pathologic diagnosis.

■ All potential regional lymph node basins should be palpated for the presence of clinically apparent disease. This examination should include the epitrochlear and popliteal minor nodal basins when the primary melanoma is located distal to the elbow and knee, respectively.

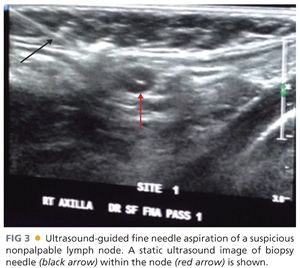

■ Palpable lymph nodes suspicious for metastatic disease should be assessed by either direct fine needle aspiration or further examined with ultrasound and biopsied with ultrasound guidance if confirmed to be radiographically suspicious. Such data may obviate the need for SLN biopsy in that basin and instead invoke a formal radiographic staging evaluation prior to carrying out a therapeutic lymph node dissection of the affected lymph node basin(s).

HISTOLOGIC EVALUATION OF THE PRIMARY MELANOMA

■ An experienced dermatopathologist should review all pathology slides related to the melanocytic lesion in question to both confirm the diagnosis of melanoma as well as to provide the microstaging (tumor thickness, ulceration status, and mitotic rate) information and other relevant adverse histologic features (see earlier discussion).

■ The decision to proceed with an SLN biopsy should be based on the earlier described established criteria. In some situations, however, the primary lesion is essentially intact and the diagnostic biopsy represents only a small sampling of the entire lesion or very superficial in depth. This type of biopsy may accurately render a definitive diagnosis of melanoma but may lack the histologic features needed to recommend an SLN biopsy. In this situation, the entire lesion should be narrowly removed as an excisional biopsy for complete histologic evaluation.

PREOPERATIVE RADIOGRAPHIC STUDIES

■ Although symptom-directed preoperative radiographic imaging is a good practice in patients with newly diagnosed melanomas, generally speaking, most newly diagnosed early stage patients are asymptomatic; therefore, no special radiographic imaging is required or recommended prior to performing an SLN biopsy for most primary melanoma patients.19 In the asymptomatic patient, extensive radiographic staging is more likely to result in false-positive rather than true positive findings. One possible exception would be the patients with both very thick (>4 mm) and ulcerated primary lesions. Many surgeons would obtain complete radiographic staging inclusive of computed tomography (CT) of chest/abdomen/pelvis or positron emission tomography (PET) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain routinely for this high-risk group.19

■ In contrast, in patients with a locally metastatic lesion or a limited number of in-transit metastases for whom an SLN biopsy is being considered as part of the definitive surgical management, a thorough preoperative radiographic staging evaluation should be performed.19

■ As mentioned earlier, ultrasound examination should be performed in patients with suspicious palpable nodes. Furthermore, ultrasound evaluation of the regional nodal basins should also be used as an adjunct to physical examination particularly of the axilla, in obese patients, with thick and ulcerated melanomas to evaluate for the presence of macroscopically involved nodes. In these situations, the sensitivity of physical examination is low and the risk of harboring synchronous macroscopically involved nodes is relatively high. Ultrasound examination suspicious for nodal involvement can be confirmed with an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FIG 3).

■ The success of any SLN program is dependent on the preoperative determination of the lymphatic drainage patterns from the primary melanoma site. Although the nodal basins at risk in extremity melanomas are relatively predictable, such is not the case for head and neck and trunk melanomas where lymphatic drainage patterns are considered ambiguous or unpredictable. Preoperative identification of lymphatic drainage patterns is accomplished with lymphoscintigraphy.20,21

PREOPERATIVE LYMPHOSCINTIGRAPHY

■ Once the decision is made to perform an SLN biopsy, the most important preoperative decision is whether or not to perform a lymphoscintigraphy.

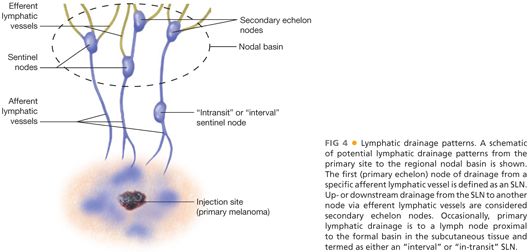

■ The technique of cutaneous lymphoscintigraphy provides an objective description of the lymphatic drainage pattern from a primary cutaneous lesion to the nodal basin(s) that receive direct afferent lymphatic drainage. Through the use of external gamma camera images, the migration of the radioactive tracer that is injected intradermally (where the invasive melanoma cells are located) at the site of the primary tumor can be visualized to determine the following: (1) the major lymph node basin(s) receiving direct lymphatic drainage, (2) number and relative location of sentinel nodes within the basin, and (3) the existence and location of SLN(s) located outside of a formal lymph node basin, referred to as either “interval” or ”in-transit” SLNs that are located in the subcutaneous tissues between the primary tumor and the formal nodal basin or ectopic in completely unpredicted anatomic locations.22 The lymphatic drainage patterns mimic how melanoma cells metastasize within the lymphatic compartment. Approximately 5% to 10% of the time, an interval or in-transit SLN pattern will be identified during lymphoscintigraphy on the trunk; these nodes are just as likely to be involved with metastatic disease as the SLNs in the formal nodal basins.22 FIG 4 provides a simplified schematic of potential lymphatic drainage patterns.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree