3 Secondary breast augmentation

Synopsis

A defined process that encompasses careful patient selection, preoperative planning and education, precise surgical technique and standardized postoperative care will help to prevent the need for secondary augmentation surgery. It is never as easy to obtain an excellent result as it is at the time of initial implant insertion.

A defined process that encompasses careful patient selection, preoperative planning and education, precise surgical technique and standardized postoperative care will help to prevent the need for secondary augmentation surgery. It is never as easy to obtain an excellent result as it is at the time of initial implant insertion.

A thorough understanding of the problems as they relate to patient expectations, soft tissue changes, implant characteristics and implant/pocket relationships are necessary before proceeding with revision surgery.

A thorough understanding of the problems as they relate to patient expectations, soft tissue changes, implant characteristics and implant/pocket relationships are necessary before proceeding with revision surgery.

Patients must clearly understand the risk/benefit equation for any revision procedure. Minor revisions should be performed with caution, as there is always a possibility of leaving the patient with a more significant problem.

Patients must clearly understand the risk/benefit equation for any revision procedure. Minor revisions should be performed with caution, as there is always a possibility of leaving the patient with a more significant problem.

The treatment of capsular contracture should recognize the likely etiologic factors of subclinical infection and biofilm formation. Consideration should be made for exchange to a new implant and insertion of the implant in a new soft tissue environment, either through capsulectomy or site change.

The treatment of capsular contracture should recognize the likely etiologic factors of subclinical infection and biofilm formation. Consideration should be made for exchange to a new implant and insertion of the implant in a new soft tissue environment, either through capsulectomy or site change.

Implant malposition is a problem of the implant pocket. Treatment requires either an adjustment to the existing pocket or a site change to a new pocket.

Implant malposition is a problem of the implant pocket. Treatment requires either an adjustment to the existing pocket or a site change to a new pocket.

Rippling or implant edge palpability can be minimized by selecting an implant size that matches the dimensions of the patient’s soft tissues and by ensuring adequate soft tissue coverage through proper pocket selection.

Rippling or implant edge palpability can be minimized by selecting an implant size that matches the dimensions of the patient’s soft tissues and by ensuring adequate soft tissue coverage through proper pocket selection.

Introduction

There are many reasons why a woman presents for secondary implant surgery, however the most common reason is for the management of capsular contracture.1 Implant malposition is another common presentation and can be categorized into malpositions that are superior, inferior, lateral or medial. Other common indications include the management of rippling or implant edge palpability, size change, device failure and finally the correction of soft tissue changes secondary to hematoma, infection, radiation or previous surgery. Regardless of the presentation, the management of the secondary implant patient requires a systematic approach to identify the underlying problems, recognize the limitations, and develop a plan that is safe and maximizes the chances for a predictable outcome.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

A detailed history should include patient goals and expectations, general health and an assessment of risk factors for compromised healing including smoking history, systemic illness or previous radiation to the breast. The patient’s breast health should be reviewed including the presence of past breast disease, family history of breast cancer and the timing of previous breast imaging. All prior breast surgeries should be well documented and operative notes obtained, if available. It is impossible to plan for a successful revision procedure without having a clear understanding as to what was done in the past. Table 3.1 lists the key points of information that should be known about previous breast procedures.

Table 3.1 Previous breast surgery

Classification

Revision breast augmentation surgery can be classified into three categories: related to the previous surgery, related to the soft tissues, related to the implant. Problems related to the previous surgery are most common. There are many decisions that go into planning any breast surgery. Improper pocket selection, improper implant selection, over or under dissection of the pocket, infection and postoperative bleeding can all affect the final outcome. Patients who would benefit from a skin tightening procedure but instead undergo the insertion of a large implant will likely have a short term gain with unacceptable results in the longer term. Figure 3.1 shows a woman who underwent bilateral subpectoral augmentation and presented with concerns of breast asymmetry. Upon surgical exploration, it was determined that the right pectoral muscle had been released along the IMF to the level of the sternum, but the left muscle had not been released at all, resulting in a unilateral high riding implant.

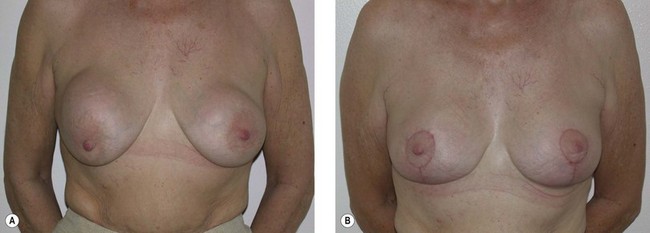

The second category includes issues related to the soft tissues. Breast tissue will undergo normal physiologic changes throughout a woman’s lifetime. These changes may include atrophy, hypertrophy, thinning or stretching. Changes are exaggerated by events such as pregnancy, breast-feeding or fluctuations in weight. The presence of an implant may hasten some of these changes, especially thinning of the skin, the development of striae and stretch marks or the development of ptosis and pseudoptosis. Even if the implant itself remains in a normal position, without complications, the development of soft tissue changes on their own can be enough to drive the need for revision surgery. Figure 3.2 shows a woman with normal, soft implants and overlying breast ptosis. This “waterfall” deformity requires a mastopexy to bring the breast tissue back up to where the implant sits.

Patient selection/indications

In situations where an implant is too wide for the breast, higher profile devices can be selected and in cases of breast asymmetry, the surgeon may select implants of different projection. Round implants produce a shape that is very different from anatomic devices and do not carry the added risk of implant rotation. Shaped implants however, have the potential to correct various asymmetries, produce a natural upper breast contour and have a low rate of capsular contracture.2–4

Treatment/surgical technique

Hints and tips

• Obtain all previous operative records, if available.

• For patients with saline implants, consider preoperative deflation to allow assessment of the soft tissues and asymmetry.

• Consider implant removal without replacement as an option in all revision procedures.

• Whenever possible, treatment of capsular contracture should include replacement of the implant, and insertion of the implant into a new soft tissue environment, either through capsulectomy or site change.

• Implant malposition is a problem of the implant pocket. Treatment requires adjusting the existing pocket or switching to a new pocket.

• Shaped implants in revision surgery require a new pocket where the dimensions of the pocket can be matched to the dimensions of the implant.

• When surgery is required on both the implant and the soft tissues, revise the implant first and then tailor the soft tissues around the new device.

The exact surgical plan will be determined by the specifics of the patient. Revision procedures may involve implant removal with or without a mastopexy. When the plan calls for insertion of a new implant, there are several fundamental decisions that need to be made. Pocket selection is a very important consideration. Options for the implant pocket are summarized in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Options for implant pocket

When the capsule around the implant is normal, there is adequate soft tissue coverage and the implant/soft tissue relationships are acceptable then the same pocket can be utilized. This is most common with revisions for size change or minor malpositions. In the case of minor contractures, an open capsulotomy or partial capsulectomy may be indicated. With Baker III/IV contractures, implant malposition, rippling or edge palpability a site change is usually indicated. When revision surgery calls for the use of a shaped gel implant, a pocket change is mandatory to allow for a precise pocket to implant fit. Site change can take the form of a capsulectomy, subglandular to subpectoral conversion, subpectoral to subglandular conversion or the creation of a new subpectoral pocket on top of a previous subpectoral capsule.5 A variation on site change is the conversion to a dual plane pocket as described by Spear.6 This approach is helpful in many cases of contracture or superior implant malposition.

A second critical consideration is the implant type, shape and size. There is no single formula that can be applied to all cases of revision augmentation but certain principles can be followed. In cases of contracture, consider the use of a textured surface implant. Several studies suggest that there is a lower capsule contracture rate with textured implants, especially when the implant is placed in the subglandular space.7,8,9 Consider the use of smaller implant sizes. Many problems following breast augmentation are as a result of soft tissue changes secondary to a large implant. It is usually better to use a smaller implant size with a skin tightening procedure rather than filling a skin envelope with larger volume devices. Shaped gel implants have a central role to play in implant selection for revision augmentation. Although they usually require a new pocket for insertion, they have many benefits including a lower contracture rate, less rippling, and shape stability. The variety of sizes allows for correction of asymmetries and the form stable nature of the gel allows the implant to shape the breast rather than the breast shaping the implant. Selection of the implant size must be based on defined measurements of implant height, width and projection to insure stability of the implant under the soft tissues.2,10

The final preoperative decision relates to the soft tissues. In cases of ptosis, glandular ptosis, skin stretch, asymmetry or nipple malposition, an alteration to the soft tissue envelope may be necessary (Fig. 3.3). Combining a mastopexy with revision of an augmentation is a complex procedure with many variables, some unpredictable. It should be undertaken with caution and only in patients with few risk factors for delayed wound healing. The soft tissues should be handled with extreme care and all skin undermining should be kept to a minimum to decrease the likelihood of skin flap or nipple loss.

Contracture

Capsular contracture is classified according to the classification proposed by Baker. The Baker Classification is still used today and is very simple. The original Baker classification defines four classes11,12:

• Class I: Breast absolutely natural; no one could tell breast was augmented

• Class II: Minimal contracture: I can tell surgery was performed but patient has no complaint

• Class III: Moderate contracture: patient feels some firmness

• Class IV: Severe contracture: obvious just from observation.

Capsular contracture represents the most common reason for secondary breast implant surgery.1 The treatment of capsular contracture begins with prevention. Multiple factors have been implicated in the development of contracted capsules and they are listed in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Etiology of capsular contracture

Many of these factors can be controlled through precise surgical technique, proper patient and implant selection, patient education and defined post surgical protocols. Maintaining a clean, non contaminated pocket is critical in preventing contractures. The author places an OpSite shield over the nipple at the start of surgery to minimize contamination from the lactiferous ducts. After creation of the pocket, irrigation is performed with an antiseptic solution. Many recommendations have been made as to the ideal solution for irrigation and include betadine, bacitracin and antibiotic solutions. Adams has published extensively on this area and recommends a triple antibiotic mixture that includes 50 mL of povidone-iodine, 1 g of cefazolin and 80 mg of gentamicin in 500 mL normal saline.13 This author has used a 50/50 mixture of povidone-iodine and normal saline for 15 years with good success. Following preparation of the pocket, the surgical gloves are changed prior to opening the implants. The implants are bathed in the irrigation solution and then inserted. Various techniques have been reported for implant insertion. These range from cleaning the skin around the incision to a complete no touch technique.14 Other options include using an insertion sleeve or a lubricated funnel. Prophylactic antibiotics are given prior to surgery and for several days after surgery.

There are very few nonsurgical options for the treatment of established capsular contractures. In 2002, Schlesinger et al. reported on the use of Zafirlukast (Accolate) for the nonsurgical treatment of capsules.15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree