This article addresses the use of scar revision surgery as it relates to the use of Z-plasty, W-plasty, and geometric broken line closure. Each of these techniques is discussed in detail and the author provides perspectives regarding the indications, advantages, and limitations of each procedure. The surgeon should be experienced with each of these and apply these methods as appropriate. As with any technique, careful preoperative planning along with meticulous execution will lead to optimal results.

Most scars are traumatic in nature and their length and orientation result from the initial injury and repair. The scar reflects the degree and depth of the injury and whether or not the skin edges were torn, frayed, or beveled. The amount of skin loss affects not only the appearance of the scar but the degree of distortion involving adjacent structures. In addition to the extent of injury and soft-tissue loss, there are multiple other factors affecting the degree of the scar deformity. These factors include the orientation of the scar, the position of the scar with respect to facial landmarks, the age of patient, the genetic factors affecting healing and scar formation, and the techniques used in wound closure.

Scar revision procedures are designed to optimize the appearance of the scar. An ideal scar is one that is thin and flat, has a good color match with the surrounding skin, and is oriented along the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). Scar revision procedures are designed to change the characteristics of the scar in such a way that it becomes a more ideal scar. There are limitations imposed by the shape and size of the scar, neighboring facial landmarks, and the variabilities of healing.

In counseling patients about scar revision, it is important to emphasize that the procedure is designed to trade a poor scar for a better scar. Misconceptions about creating an invisible scar must be corrected.

This article addresses the use of scar revision surgery as it relates to irregularization techniques. Each of these is discussed in detail and the author will provide his perspectives with respect to the indications, advantages, and limitations of each procedure.

Timing of scar revision

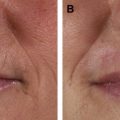

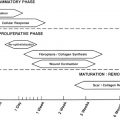

Scars tend to improve spontaneously as they mature. The timing of scar revision has traditionally been in the range of 6 to 12 months; however, for some scars there is enough deformity that consideration can be given for earlier scar revision. One rule of thumb is what the author and colleagues have termed the plateau phenomenon; that is, if patients and the physician observe the scar over a 2- to 3-month period and there is no significant improvement, a decision can be made as to whether scar revision is indicated. Typically, scar revision is not performed before 3 months following injury. It is important to note the resolution of the acute inflammatory changes in the tissues surrounding the scar. The adjacent skin should be soft, supple, and nontender. Ideally, there should be no significant residual erythema, edema, or induration.

The necessity and timing of scar revision is a joint decision made by the physician and the patient. The role of the physician is to inform and educate patients about what options exist and what degree of improvement can be expected. If there is a question about whether scar revision is indicated, it is always best to err on the side of waiting. In general, scars improve over time, and unless there are functional issues, there is usually no downside to further observation before surgical intervention is entertained.

Types of scar deformities

The spectrum of posttraumatic scar deformities is quite significant. Some scars are hypertrophic, being thick, wide, and raised. Atrophic scars are thin, wide, and flat. Scars may be depressed, stellate, or multinodular (lumpy bumpy). On occasion, patients may develop a thin scar, but it might have a poor color match or be oriented in the wrong direction. Scars can also be associated with distortion of adjacent structures, such as misalignment of the vermilion border, traction on the nasal ala, or creating a contour deformity of the lower eyelid. The author’s classification system is shown in ( Table 1 ).

| Scar | Deformity |

|---|---|

| Hypertrophic scar | Thick, raised |

| Atrophic scar | Thin, flat |

| Depressed scar | Indented |

| Irregular scar | Multinodular, stellate, and so forth |

| Poorly oriented scar | Good scar, wrong direction |

| Scar with poor color match | Good scar, wrong color |

| Scar associated with distortion of adjacent structure | Elevation of brow, traction on nasal ala, and so forth |

Types of scar deformities

The spectrum of posttraumatic scar deformities is quite significant. Some scars are hypertrophic, being thick, wide, and raised. Atrophic scars are thin, wide, and flat. Scars may be depressed, stellate, or multinodular (lumpy bumpy). On occasion, patients may develop a thin scar, but it might have a poor color match or be oriented in the wrong direction. Scars can also be associated with distortion of adjacent structures, such as misalignment of the vermilion border, traction on the nasal ala, or creating a contour deformity of the lower eyelid. The author’s classification system is shown in ( Table 1 ).

| Scar | Deformity |

|---|---|

| Hypertrophic scar | Thick, raised |

| Atrophic scar | Thin, flat |

| Depressed scar | Indented |

| Irregular scar | Multinodular, stellate, and so forth |

| Poorly oriented scar | Good scar, wrong direction |

| Scar with poor color match | Good scar, wrong color |

| Scar associated with distortion of adjacent structure | Elevation of brow, traction on nasal ala, and so forth |

Scar revision techniques

It is important for the surgeon to identify the problematic nature of the scar: whether it is raised, too wide, too thin, depressed, causing distortion of a facial landmark, or running perpendicular to the relaxed skin tension lines. Once the decision has been made to proceed with the scar revision, the goals of the procedure should be identified ( Table 2 ).

| Make the scar narrower and flatter |

| Reorient or reposition the scar |

| Fill in the depression |

| Break up the scar |

| Smooth out an irregular scar |

| Improve the color of the scar |

| Correct facial landmark distortion |

Multiple surgical procedures have been described to improve facial scars. These procedures include scar repositioning, simple excision, serial excision, and the 3 techniques discussed here. This article focuses on irregularization techniques: Z-plasty, W-plasty, and geometric broken line closure (GBLC). The goals of this article are to provide the reader with the indications for each specific technique, the advantages these techniques offer, and the limitations that are inherent with each technique. In addition, practical tips with respect to the planning and execution of each operative technique are discussed.

Z-plasty

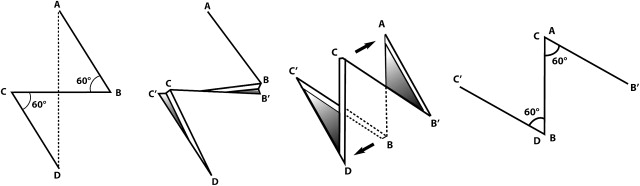

Z-plasty can be used to help reorient a scar so that the new scar lies in a more favorable position with respect to the relaxed skin tension lines. The Z-plasty procedure represents a double transposition flap, where the scar to be excised lies along the central limb of the Z-plasty with 2 peripheral limbs of equal length placed parallel to each other ( Fig. 1 ). The resulting central limb will be perpendicular to the original scar.

Clinical Application

The indications for Z-plasty include scars that are greater than 30° off the RTSLs, scars that are contracted, and scars that form webs. With the classic Z-plasty, each limb is the same length and the angles of the 2 triangular flaps are 60°. Given these parameters, for any given scar there are 2 options for designing the limbs of the Z. It is important to choose the option that will result in the new scars lying in a more favorable position with respect to the RSTLs ( Fig. 2 ). On the face, the 3 limbs of the Z are designed to be equal, each being 5 mm in length. The nature of the Z-plasty precludes the entire scar from being parallel to the RSTLs. In addition to improving the orientation of the scar, a multiple Z-plasty breaks up the scar. This irregularization and new orientation makes the scar less conspicuous. Although there is little scientific evidence related to scar revision procedures, it would seem to make sense that creating different vectors of tension might be an advantage in avoiding scar hypertrophy and contraction.