Sarcoidosis: Introduction

|

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown cause. The lung is the most commonly affected organ, but the skin is frequently involved.1 The first descriptions of sarcoidosis in the late 1800s were limited to its skin manifestations.1 The term sarcoidosis is derived from Caesar Boeck’s 1899 report of what he described as “multiple benign sarkoid of the skin,” because he believed the lesions resembled sarcomas but were benign.2

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis occurs worldwide and affects all ages and races. Disease onset is most often in the third decade of life, although a smaller second peak occurs in people older than 50 years.1 The prevalence rate is slightly higher in women.1 Sarcoidosis is more frequent away from the equator. The highest prevalence of sarcoidosis is found in Caucasians in Denmark, Sweden, and, in the United States, in persons of African descent.1 In the United States, the lifetime risk of sarcoidosis is 2.4% in African-Americans and 0.85% in Caucasians.3 The age-adjusted annual incidence rate of sarcoidosis in the United States is 35.5 per 100,000 for African-Americans and 10.9 per 100,000 for Caucasians.3 The frequency and severity of the disease also vary between different ethnicities and races. African-Americans tend to have more severe disease, whereas Caucasians are more likely to present with asymptomatic disease.4,5 African-Americans are also more likely to have extrapulmonary disease,6 require treatment,7 develop new organ involvement,8 and have a lower rate of clinical recovery than Caucasians.5,8 The disease is more common in life-long nonsmokers.9

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The current understanding is that the development of sarcoidosis requires at least three major events: (1) exposure to antigen(s), (2) acquired cellular immunity directed against the antigen and mediated through antigen-presenting cells and antigen-specific T lymphocytes, and (3) the appearance of immune effector cells that promote a nonspecific inflammatory response.10 The identity of the putative antigen(s) of sarcoidosis is unknown.

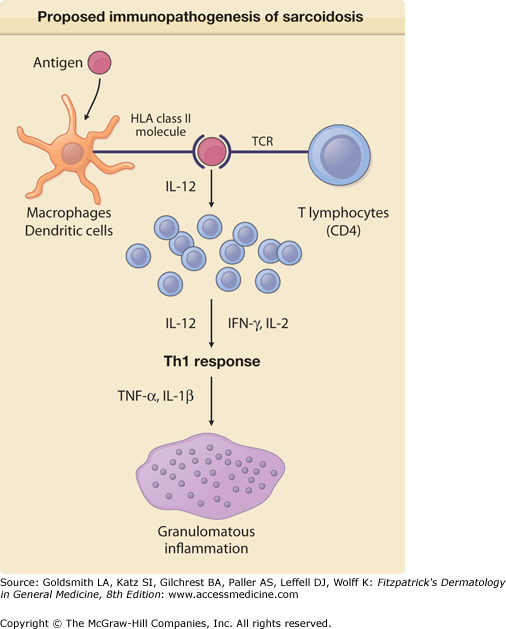

Presumably, antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages recognize, process, and present the processed antigen to CD4+ T cells of the T helper 1 type (Fig. 152-1). The processed antigen is presented to these lymphocytes via HLA class II molecules on the antigen-presenting cells that have undergone enhanced expression from exposure to the sarcoidosis antigen and possibly interferon-γ (IFN-γ).10,11 These activated macrophages produce interleukin (IL)-12, which induces lymphocytes to shift toward a T helper 1 profile and causes T lymphocytes to secrete IFN-γ. These activated T cells release IL-2 and chemotactic factors that recruit monocytes and macrophages to the site of disease activity. IL-2 and other cytokines also expand various T-cell clones. IFN-γ further activates macrophages and transforms them into giant cells.11 Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-2, and other cytokines may also be important in stimulating macrophages.12Figure 152-1 displays the major features of the presumed immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

Figure 152-1

Proposed immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis. An antigen, presently unknown, is engulfed and processed by an antigen-presenting cell (macrophage or dendritic cell). The processed antigen is presented to a T-cell receptor (TCR) of a T lymphocyte via an HLA class II molecule. Once the HLA receptor and TCR have bound the processed antigen, numerous lymphokines and cytokines of the T helper 1 (Th1) class are released that lead to T-cell proliferation, recruitment of monocytes, and eventual granuloma formation. A few of these lymphokines and cytokines are shown, with those released by the antigen-presenting cells on the left and those released by lymphocytes on the right. IFN = interferon; IL = interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

A variety of candidate antigens have been suggested as provocative agents for the cascade of immunologic events that eventuate in sarcoidosis. Infectious agents such as mycobacteria,13 Propioni-bacterium acnes,14 and Chlamydia15 have been associated with sarcoidosis. Mineral dusts, such as silica, iron,16 and titanium,17 also have been associated with sarcoidosis as have combustible wood products because the disease has been found more commonly in individuals who use wood stoves.18 Interestingly, firefighters have been found to be at greater risk of developing sarcoidosis.19

Genetics play a major role in determining susceptibility to sarcoidosis, as it is more common in relatives of an affected person than in individuals in the general population.20 Genes coding for HLA class II antigens are thought to be prime candidates for a role in the development of the disease because these molecules present exogenous peptides to CD4+ T-cell receptors. Numerous studies in various ethnic groups have shown a relationship of HLA antigens to the development of disease, protection from disease, good prognosis, poor prognosis, acute disease, chronic disease, and various phenotypic expressions of sarcoidosis.21

The interplay of antigenic and genetic factors suggests that there may be multiple causes of sarcoidosis. Patients may have to experience a specific interaction between one or several exposures and be genetically programmed to one or several abnormal immunologic responses. Each putative antigen may be associated with a specific HLA class II molecule and T-cell receptor.

Clinical Findings

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often delayed for months to years because symptoms are nonspecific and can relate to involvement of any organ.22

Thirty to sixty percent of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis are asymptomatic.23 Other than the lung, the skin, eye, liver, and peripheral lymph nodes are commonly involved. Consequently, sarcoidosis should be considered in a patient with skin lesions and concomitant pulmonary symptoms, eye complaints, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, or peripheral lymphadenopathy. In addition, the cytokines associated with the granulomatous inflammation of sarcoidosis may cause constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, malaise, and weight loss.

Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis may occur before, coincident with, or after systemic involvement. Specific cutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic. Pruritus and pain are rare. Cosmetic disfigurement is the most common complaint. Erythema nodosum associated with sarcoidosis is indistinguishable from erythema nodosum unassociated with sarcoidosis (see Chapter 70).

Classically, lesions are divided into two categories: (1) specific and (2) nonspecific. Specific lesions have granulomas on biopsy. Nonspecific skin findings are reactive and do not exhibit sarcoidal granulomas.

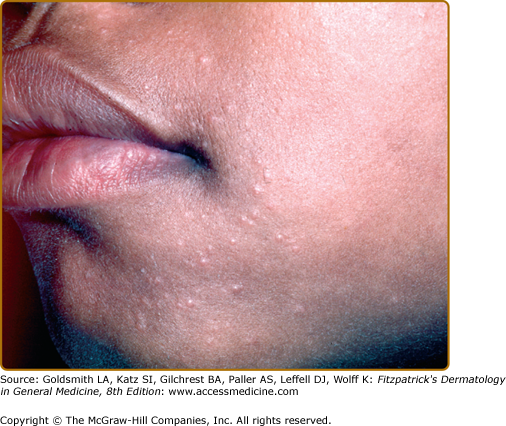

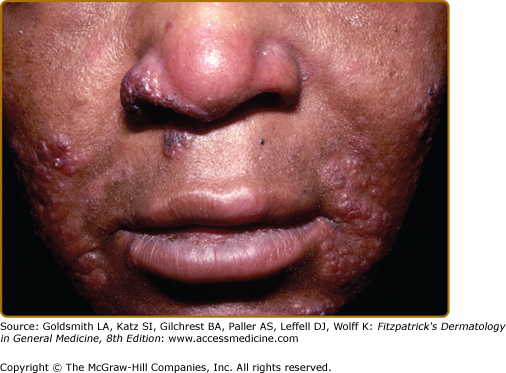

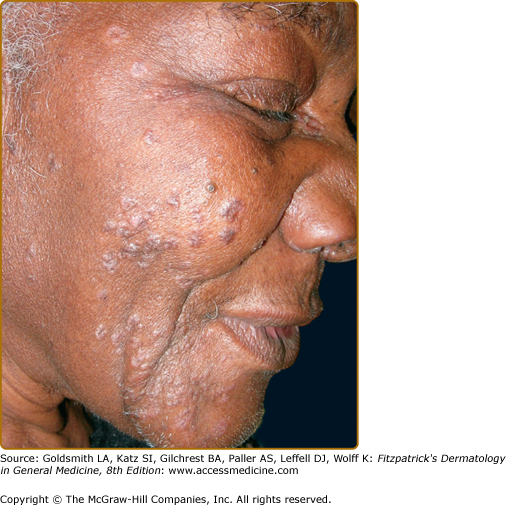

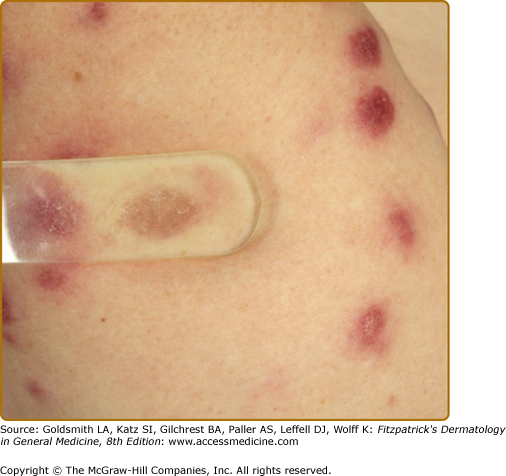

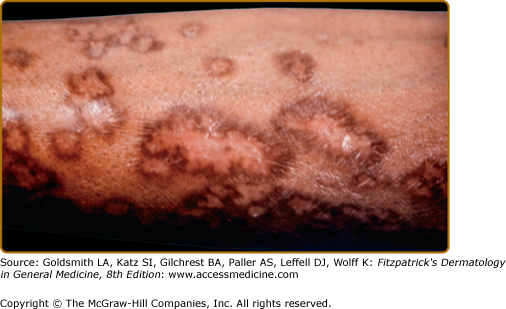

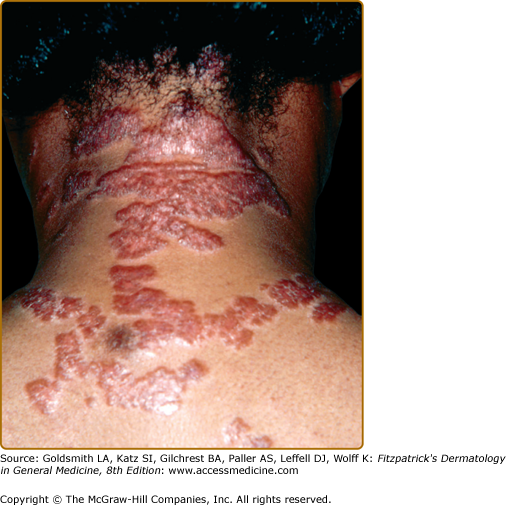

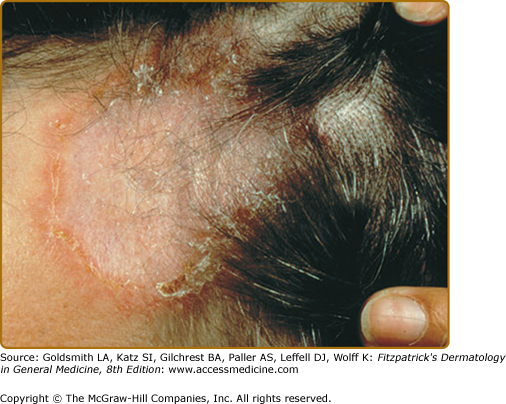

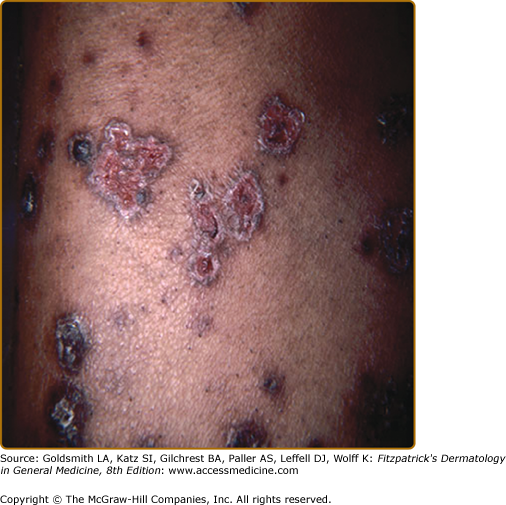

Specific sarcoidal lesions most often are found on the head and neck (Figs. 152-2, 152-3, and 152-4) but may occur symmetrically or asymmetrically on any part of the skin and mucosa. Almost all morphologies have been reported, including macules, papules, patches, plaques, and nodules. Alopecia occurs with scalp involvement, and nail changes also occur. Specific lesions of sarcoidosis may be scaly, telangiectatic, or atrophic. Despite the diversity in appearance, there are several clinical presentations that are classically associated with cutaneous sarcoidosis.

The most common presentation is the papular form (see Figs. 152-2, 152-3, and 152-4). These firm, 2–5-mm papules often have a translucent red-brown or yellow-brown appearance. The yellow-brown color has been likened to “apple jelly” and is accentuated with diascopy (Fig. 152-5). In addition to the color change, the underlying granulomas have a nodular quality that can also be appreciated with diascopy. The apple jelly appearance and nodules are not pathognomonic for sarcoidosis, as other granulatomous skin conditions, such as lupus vulgaris (see Chapter 184), may exhibit similar diascopic properties. Epidermal changes may or may not be present, but often the lesions have a waxy appearance, which reflects mild epidermal atrophy. Papular lesions occur most commonly on the face and neck, with a predilection for periorbital skin (see eFig. 152-5.1). Annular plaques (Fig. 152-6), nonannular plaques (Fig. 152-7 and see eFig. 152-7.1), and nodules (Fig. 152-8) may develop from these papular lesions and may or may not retain the classic translucent quality of the papules.

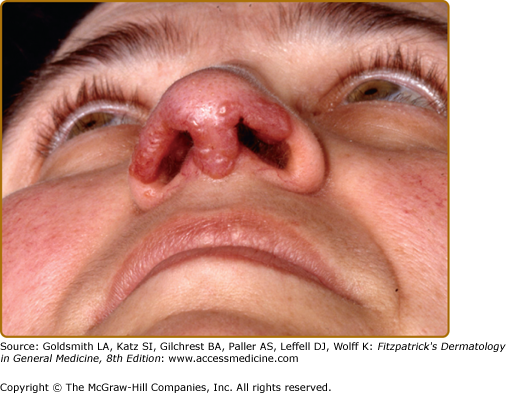

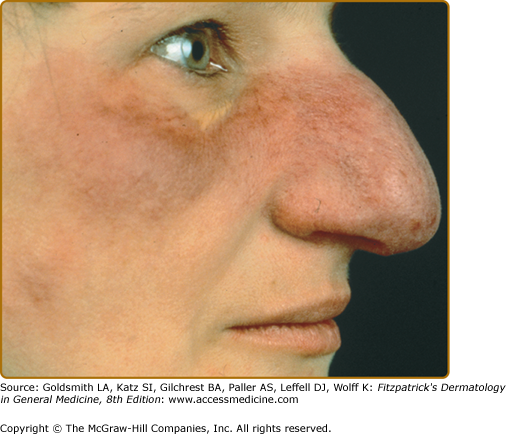

Lupus pernio describes the relatively symmetric, violaceous, indurated plaques and nodules that occur on the nose, earlobes, cheeks, and digits (Figs. 152-9, 152-10, and 152-11). This clinical variant of sarcoidosis is distinctive and has been associated with systemic involvement. Lupus pernio is associated with a higher prevalence of upper respiratory tract disease.24 Lupus pernio lesions may directly extend into the nasal sinus, leading to epistaxis, nasal crusting, and sinus bone involvement.

Figure 152-9

Lupus pernio along the nasal rim. This patient also had sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) (see Section “Other Organs”).

Angiolupoid lesions are pink papules and plaques with prominent telangiectasias that usually occur on the face (see eFig. 152-11.1) and may be a variant of lupus pernio, as both lesions usually appear on the face and can be violaceous.25,26 However, angiolupoid lesions tend to be less numerous than the papular and lupus pernio forms.26

Rarely, sarcoidosis can present as persistent subcutaneous nodules (Darier-Roussy sarcoid).27 The nodules may be tender or painless and preferentially occur on the extremities.

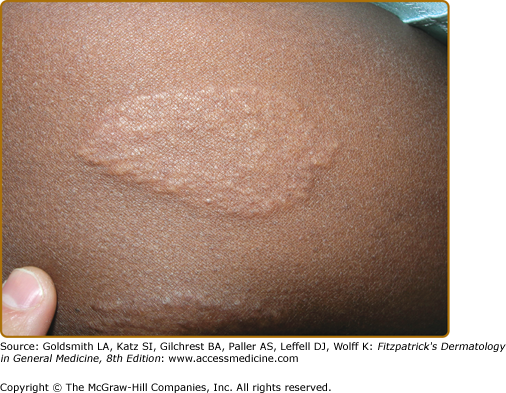

Cutaneous sarcoidosis occurs preferentially within scar tissue, at traumatized skin sites, and around embedded foreign material such as silica. Scars become inflamed and infiltrated with sarcoidal granulomas (Fig. 152-12). Inflammation of old scars (see eFig. 152-12.1) may parallel or precede systemic disease activity. Infiltrated scars may be tender or pruritic. Scar sarcoidosis may be the only cutaneous finding in a patient with systemic sarcoidosis; therefore, it is important to closely examine scar tissue in patients suspected of having the disease. The presence of sarcoidal granulomas surrounding foreign material does not establish the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, nor does foreign material in the presence of granulomas exclude the diagnosis.28 Other signs of systemic or cutaneous involvement are required to confirm the diagnosis.

Alopecia occurs with involvement of the scalp and may be scarring or nonscarring (see eFig. 152-12.2).29–32 Biopsy shows noncaseating granulomas. Its reversibility is dependent on the degree of destruction of hair follicles.

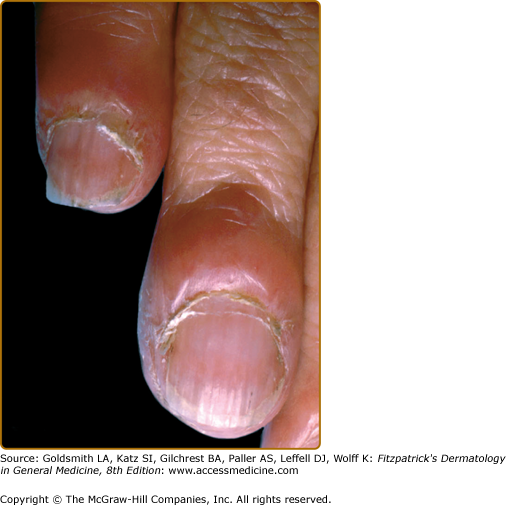

Sarcoidosis may cause nail plate deformation and discoloration, but the incidence is very low.33 There may be clubbing, (Fig. 152-11) subungual hyperkeratosis, and even nail plate destruction. Nail manifestations may result from granulomas in the nail matrix or from involvement of adjacent bone.

Sarcoidal granulomas may cause papules and plaques of the mucosal surfaces and tongue. Sarcoidosis is one cause of Mikulicz syndrome, the bilateral enlargement of the lacrimal (see eFig. 152-12.3), parotid, sublingual, and submandibular glands.

A myriad of additional clinical presentations have also been reported. These include ichthyosis,34 erythroderma,29 ulcerations (see eFigs. 152-12.4 and 152-12.5),35 morphea-form plaques,36 lichen niditus-like papules,37 folliculitis-like lesions,38 psoriasiform plaques,39 hypopigmented areas,40 gyrate erythema,41 verrucous lesions,38 faint erythema, penile (see eFig. 152-12.6) and vulvar lesions,42,43 palmar erythema,44 discoid lupus-like plaques,45 lower extremity edema,46 lesions mimicking tuberculoid leprosy (see eFig. 152-12.7) polymorphous light eruption,38 and pustular lesions.38

Erythema nodosum (see Chapter 70) is the main nonspecific cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis (prevalence of approximately 17%). Erythema nodosum with bilateral hilar adenopathy, arthralgias, and fever is frequently the initial manifestation of sarcoidosis and is called Löfgren syndrome. These patients tend to have an acute form of sarcoidosis with eventual resolution.

Other nonspecific cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis are much less common. The neutrophilic dermatoses, Sweet disease and pyoderma gangrenosum, have been reported as nonspecific cutaneous sarcoid lesions. Most of the sarcoid patients with Sweet disease lesions or pyoderma gangrenosum have concomitant erythema nodosum.47 Nonspecific erythematous eruptions resembling viral exanthems or drug reactions without histologic evidence of granulomatous inflammation occur rarely with acute sarcoidosis. Additionally, patients with sarcoidosis may have pruritus without granulomatous infiltration, leading to prurigo nodules.25 Erythema multiforme had been regularly cited as a nonspecific cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis,38 but reports of histologically proven erythema multiforme with interface dermatitis associated with sarcoidosis are virtually nonexistent in the literature,25,38,48,49 and any association is probably coincidental. Erythroderma and lower extremity swelling have been described as both specific and nonspecific lesions of sarcoidosis.25,46,50,51

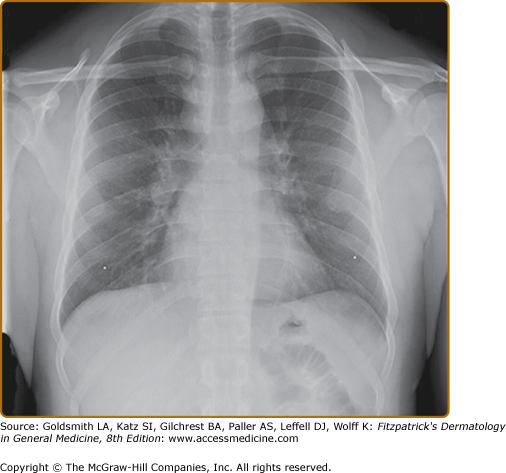

The lung is the most common organ involved with sarcoidosis. Findings on pulmonary examination are usually absent. Patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis are often asymptomatic, with the disease detected on a screening chest radiograph. Common symptoms include dyspnea, cough, chest pain, and wheezing. The chest radiograph is abnormal in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis. Bilateral hilar adenopathy is noted in 50%–85% of cases (see eFig. 152-12.8). Pulmonary parenchymal infiltrates are seen in 25%–60% of cases.

Chest computed tomography (CT) reveals more thoracic disease than can be appreciated on the chest radiograph. CT is superior to the chest radiograph in detecting thoracic involvement with sarcoidosis, but there is insufficient evidence that CT has a clinical role in the management of pulmonary sarcoidosis.52

In sarcoidosis patients with normal lung parenchyma on chest radiograph, pulmonary function tests are abnormal in 20%–40% of cases. When the chest radiograph is abnormal, pulmonary function tests are abnormal in 50%–70% of cases.

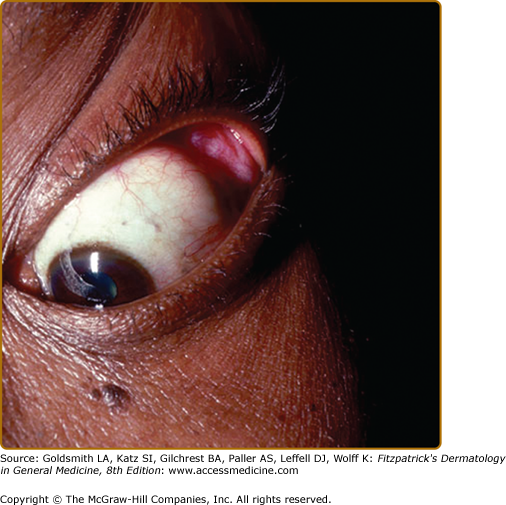

The eyes are involved in one-fourth to three-fourths of sarcoidosis patients.53 Eye involvement with sarcoidosis is potentially vision threatening, and the patient may be asymptomatic. For this reason, every patient diagnosed with sarcoidosis requires an ophthalmologic examination.53 Redness, burning, itching, or dryness are the most common ocular symptoms when present. Any portion of the eye may be involved, and eye involvement may be the first manifestation of the disease.53 Uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation and can lead to cataracts and glaucoma. Other ocular manifestations include conjunctivitis, lacrimal gland involvement causing kerato-conjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes), and optic neuritis, which may rapidly lead to loss of vision. Heerfordt syndrome includes fever, parotid gland enlargement, facial palsy, and anterior uveitis.1

Hepatic involvement is common at disease onset but usually does not cause signs or symptoms.54 Although histologic evidence of hepatic sarcoidosis is present in more than one-half of sarcoidosis patients,55 signs of organ dysfunction due to hepatic sarcoidosis are far less common.54 Hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, and pruritus are present in only 15%–25% of patients with hepatic sarcoidosis. An increased serum alkaline phosphatase level occurs in approximately one-third of patients,56 but it is rarely associated with permanent hepatic dysfunction and therefore does not mandate treatment.54,56 Treatment is required in the rare patient with significant symptoms, evidence of synthetic dysfunction, or hyperbilirubinemia. Rarely, hepatic sarcoidosis may lead to a primary biliary cirrhosis-type picture, and portal hypertension may develop.57

Clinical evidence of cardiac involvement is found in only 5% of sarcoidosis patients,58 although myocardial granulomas have been found in approximately 25% of patients at autopsy.59 Most clinical problems are related to cardiac arrhythmias or left ventricular dysfunction.60

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree