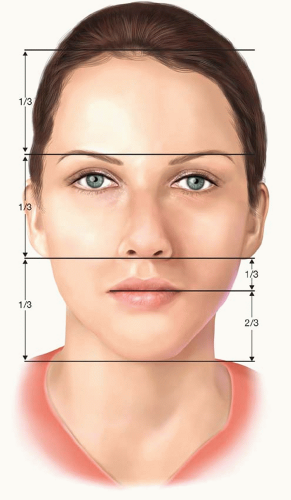

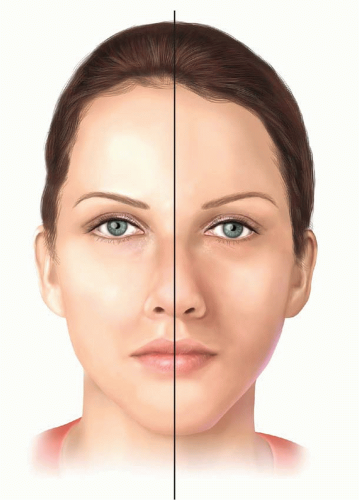

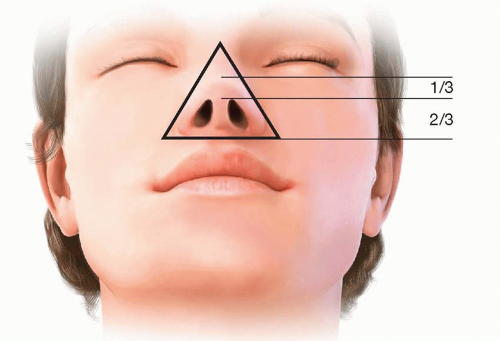

The face is divided into thirds using horizontal lines tangent to the hairline, brow (at the level of the supraorbital notch), nasal base, and chin (menton). The upper third (between the hairline and the brow) is the most variable, as it depends on the hairline and hairstyle, and therefore is the least important. The middle third lies between the brow and the nasal base. The lower third of the face can be subdivided into thirds by visualizing a horizontal line between the oral commissures (stomion). The upper third of this subdivision lies between the nasal base and the oral commissures and the lower two-thirds between the commissures and the menton (Figure 48.8). Deviation from these proportions may signal an underlying craniofacial anomaly, such as vertical maxillary excess or maxillary hypoplasia, that may need to be addressed prior to rhinoplasty (Chapter 25).

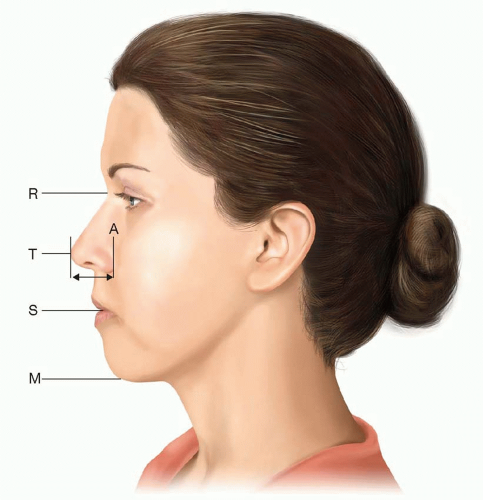

The nasal length (radix-to-tip, or R-T) should be equivalent to the stomion-to-menton distance (S-M) (Figure 48.9).

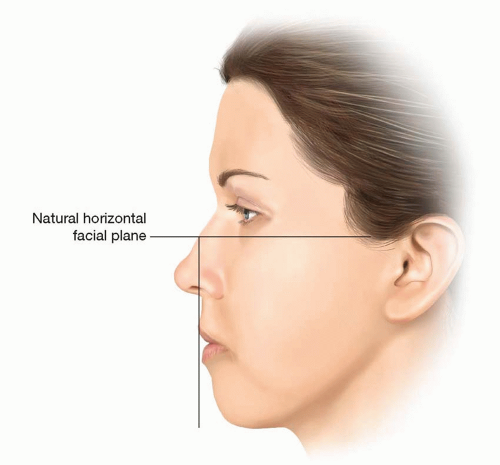

The lip-chin relationship is assessed by dropping a vertical line from a point one-half the ideal nasal length tangent to the vermillion of the upper lip. The lower lip should lie approximately 2 mm behind this line. The ideal chin position varies with gender, with the chin lying slightly posterior to the lower lip in women, but equal to the lower lip in men. Orthodontics, a chin implant, or orthognathic surgery may be necessary to improve overall facial harmony if there is a discrepancy in these relationships (Figure 48.10).

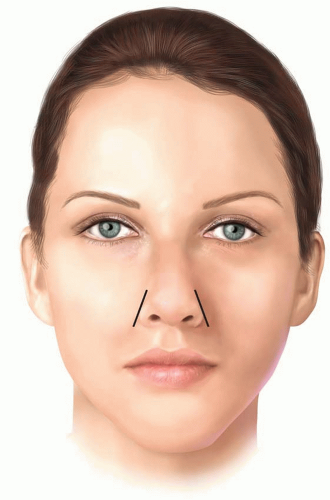

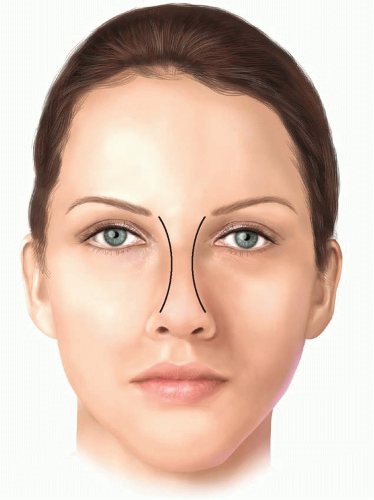

The nose itself is addressed from the anteroposterior view. A vertical line is drawn from the midglabellar

area to the menton, bisecting the nasal ridge, upper lip, Cupid’s bow, and central incisors (if the patient has normal occlusion). Any nasal deviation from this line is likely to require septal surgery (Figure 48.11).

TABLE 48.1 SYSTEMATIC NASAL ANALYSIS

Frontal view

Facial proportions

Skin type/quality—Fitzpatrick type, thin or thick, sebaceous

Symmetry and nasal deviation—midline, C-, reverse C-, S- or S-shaped deviation

Bony vault—narrow or wide, asymmetrical, short or long nasal bones

Midvault—narrow or wide, collapse, inverted V deformity

Dorsal aesthetic lines—straight, symmetrical or asymmetrical, well or ill defined, narrow or wide

Nasal tip—ideal/bulbous/boxy/pinched, supratip, tip-defining points, infratip lobule

Alar rims—gull shaped, facets, notching, retraction

Alar base—width

Upper lip—long or short, dynamic depressor septi muscles, upper lip crease

Lateral view

Nasofrontal angle—acute or obtuse, high or low radix

Nasal length—long or short

Dorsum—smooth, hump, scooped out

Supratip—break, fullness, pollybeak

Tip projection—over- or underprojected

Tip rotation—over- or underrotated

Alar-columellar relationship—hanging or retracted alae, hanging or retracted columella

Periapical hypoplasia—maxillary or soft-tissue deficiency

Lip-chin relationship—normal, deficient

Basal view

Nasal projection—over- or underprojected, columellar-lobular ratio

Nostril—symmetrical or asymmetrical, long or short

Columella—septal tilt, flaring of medial crura

Alar base—width

Alar flaring

From Rohrich RJ, Ahmad J. Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 128:49e-73e.

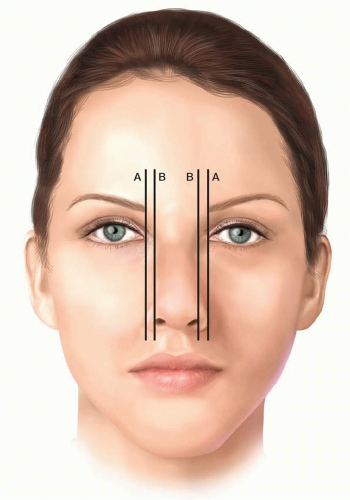

The curvilinear dorsal aesthetic lines are traced from their origin at the supraorbital ridges toward their convergence at the level of the medial canthal ligaments. From here, they flare slightly at the keystone area and then track down to the tip-defining points, slightly diverging from each other along the dorsum during their course. The ideal width of the dorsal aesthetic lines should be approximately equivalent to the width between the tip-defining points or the interphiltral distance (Figure 48.12).

The normal alar base width is equivalent to the intercanthal distance, or the transverse dimension from the medial to lateral canthus. If the alar base width is greater than the intercanthal distance, the underlying etiology is examined. If the discrepancy is the result of a narrow intercanthal distance, it is better to maintain a slightly wider alar base. If there is true increased interalar width, a nostril sill resection may be indicated. If the increase in width is secondary to alar flaring (greater than 2 to 3 mm outside the alar base), an alar base resection should be considered. The bony base should equal approximately 80% of the alar base width (Figures 48.13 A and B). If the bony base is greater than 80% of the alar base width, osteotomies may be required. Over-narrowing the dorsum should be avoided in males as this can lead to an “over-feminized” look.

FIGURE 48.8. The face is divided into thirds, using horizontal lines tangent to the hairline, brow, nasal base, and chin.

The alar rims are examined for symmetry. They should normally flare slightly outward in an inferolateral direction (Figure 48.14).

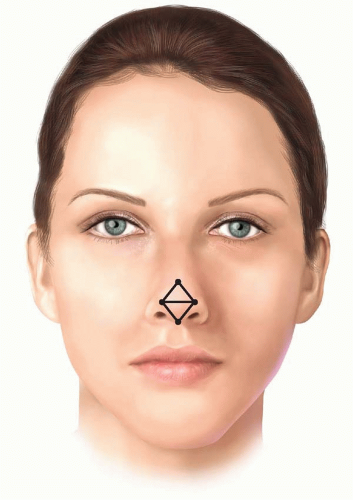

The tip is assessed by drawing two equilateral triangles with their bases opposed (Figure 48.15). The supratip break, tip-defining points, and columellar-lobular angle serve as landmarks. If these triangles are asymmetric, the patient will likely require tip modification.

The final assessment on frontal view is of the outline of the alar rims and the columella. Normally, this outline should resemble a seagull in gentle flight. If the angles

are too steep, the patient likely has an increased infratip lobular height. Conversely, if the angle/curve is too flattened, it is likely the patient has decreased columellar show, which may require columellar and/or alar rim modification (Figure 48.16).

FIGURE 48.9. The ideal nasal length is equivalent to the stomion-to-menton distance. A, ala; M, menton; R, radix; S, stoma; T, tip.

FIGURE 48.10. The ideal lower lip position is 2 mm behind a vertical line dropped from a point half the ideal nasal length along the natural horizontal facial plane.

The basal view of the nose is examined focusing on the outline of the nasal base and the nostrils themselves. The outline of the nasal base should describe an equilateral triangle with a lobule-to-nostril ratio of 1:2 (Figure 48.17). The nostril itself should have a teardrop geometry, with the long axis oriented in a slight medial direction (from base to apex).

FIGURE 48.11. Symmetry is determined by drawing a vertical line from the midglabellar area to the menton.

FIGURE 48.12. The curvilinear dorsal aesthetic lines extend from the supraorbital ridges to the tip-defining points.

FIGURE 48.13. A. The normal alar base width equals the intercanthal distance, or the width of one eye. B. The bony base should be approximately 80% of the alar base width.

Attention is turned to the lateral view, beginning with analysis of the nasofrontal angle. This angle connects the brow and nasal dorsum through a soft concave curve. The apex of this angle (radix) should lie between the supratarsal fold and the upper lid lashes, with the eyes in primary gaze. The nasofrontal angle can vary between 128° and 140°, but is ideally approximately 134° in females and 130° in males.

It is important to note that the perceived nasal length and tip projection can be altered by the position of the nasofrontal angle. For instance, the nose appears longer if the nasofrontal angle is positioned more anteriorly and superiorly than normal. In this instance, the nasofacial angle (as defined by the junction of the nasal dorsum with the vertical facial plane) is decreased and the tip projection will appear diminished (yellow line). Conversely, the nose can appear shorter if the nasofrontal angle is positioned too posteriorly and/or inferiorly. In this case, the tip may also appear more projecting (red line; Figure 48.18). Ideally, the nasofacial angle should measure 32° to 37°.

While still analyzing the lateral view, tip projection is addressed. This can be done in two ways. The first is to draw a horizontal line from the alar-cheek junction to the tip of the nose. The distance between these points should equal two things: (1) the alar base width, and (2) 0.67 × R-T (radix-to-tip) (Figures 48.19A and B). The second way to assess tip projection is to examine how much of the tip lies anterior to a vertical line tangent to the most projecting part of the upper lip vermillion. If 50% to 60% of the tip lies anterior to this line, projection is considered normal. If the tip projection is outside of these proportions, it likely will require tip modification (Figure 48.20).

The dorsum is analyzed by drawing a line from the radix to the tip-defining points. In women, the ideal aesthetic nasal dorsum should lie approximately 2 mm behind and parallel to this line, but in men, it should approach this line to avoid feminizing the nose (Figure 48.21).

The degree of supratip break is also evaluated on the lateral view. This break helps to define the nose and separate the tip from the dorsum. A slight supratip break is preferred in women but not in men.

The degree of tip rotation is assessed by evaluating the nasolabial angle, which is the angle formed between a line coursing through the most anterior and posterior edges of the nostril and a plumb line dropped perpendicular to the natural horizontal facial plane (Figure 48.22). This angle is usually 95° to 100° in women and between 90° and 95° in men.

The nasolabial angle is often confused with the columellarlobular angle, which is formed at the junction of the columella with the infratip lobule (Figure 48.23). This angle is normally 30° to 45°. A prominent caudal septum can cause

increased fullness in this area, which can give the illusion of increased rotation, despite a normal nasolabial angle.

FIGURE 48.15. Tip assessment is performed by analyzing two equilateral triangles with opposing bases.

FIGURE 48.16. The outline of the alar rims and columella should resemble a “seagull in gentle flight.”

FIGURE 48.17. The outline of the nasal base should resemble an equilateral triangle with a lobule-to-nostril ratio of 1:2.

The alar-columellar relationship is assessed by drawing a line through the long axis of the nostril and a second, perpendicular line drawn from the alar rim to the columellar rim that bisects this axis. If the alarcolumellar relationship is normal, the distance from the alar rim (“point A”) to the long axis line (“point B”) should equal the distance between the long axis line and the columellar rim (“point C”) (AB = BC ≈ 2 mm) (Figure 48.24). If abnormal, the deformity can be stratified into six classes.29 Classes I to III describe increased columellar show, while classes IV to VI demonstrate decreased columellar show. The treatment of the discrepancy varies by class.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty

Jeffrey E. Janis

Jamil Ahmad

Rod J. Rohrich

INTRODUCTION

Rhinoplasty is challenging. Over the past 20 years, the trend has shifted from ablative techniques involving reduction or division of the osseocartilaginous framework to techniques that conserve native anatomy. Cartilage sparing suture techniques and augmentation of deficient areas to correct contour deformities and restore structural support are commonly employed.1 The rhinoplasty surgeon must understand the underlying anatomy and have the ability to perform nasofacial analysis to determine the operative plan and the training to execute techniques that manipulate bone, cartilage, and soft tissue. These skills are augmented by an aesthetic eye in order to produce a result that blends harmoniously with the rest of the face.

NASAL ANATOMY

The nose consists of external skin and soft tissue, underlying osseocartilaginous framework, and ligamentous support. Familiarity with the native morphology and potential variations of each structure is essential. Furthermore, the dynamic interplay between these components must be appreciated.

Skin

The nasal skin is not uniform; its thickness, mobility, and sebaceous character vary along the length of the nose.2 The skin of the upper two-thirds is thinner, averaging 1,300 µm versus the lower one-third, which averages 2,400 µm.3 The upper two-thirds is also more mobile and less sebaceous than the skin of the nasal tip. It is important to note that a straight dorsum is actually produced by the underlying convexity in the osseocartilaginous framework combined with the aforementioned variation in dorsal skin thickness.

Muscle

While there are several muscles in the nose, two muscles are particularly important in rhinoplasty—the levator labii alaeque nasi and the depressor septi nasi. The levator labii alaeque nasi assists in maintaining the patency of the external nasal valve, while the depressor septi nasi acts to shorten the upper lip and decrease tip projection.

The effects of an overactive depressor septi must be appreciated as part of the preoperative nasofacial analysis and can be recognized by a depressed nasal tip and shortened upper lip upon animation (especially when smiling). In the subgroup of patients in which this muscle significantly alters the nasal appearance, a dissection and transposition of this muscle can be performed.7

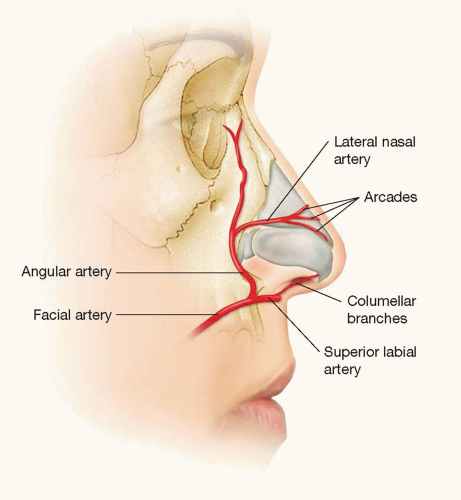

Blood Supply

The blood supply to the nose is derived both from branches of the ophthalmic artery and from branches of the facial artery (Figure 48.1). Columellar branches are present in 68.2% of patients.8,9,10 These branches are transected in the open approach by the transcolumellar incision. This leaves the lateral nasal and dorsal nasal arteries as the remaining blood supply to the tip if the open approach is used. To that end, extended alar resections are avoided, as the lateral nasal artery is found 2 to 3 mm above the alar groove. Furthermore, extensive debulking of the nasal tip is avoided as the subdermal plexus may be injured leading to skin necrosis.

The veins and lymphatics lie in a subcutaneous plane, which is superficial to the musculoaponeurotic layer in which the arteries travel. In the open approach, the dissection is performed in the submusculoaponeurotic plane just above the perichondrium in order to avoid injury to all of these structures. In this way, both bleeding and postoperative edema are minimized.

Osseocartilaginous Framework

The osseocartilaginous nasal framework is comprised of three separate vaults: the bony vault, the upper cartilaginous vault, and the lower cartilaginous vault. The bony vault is made up of the paired nasal bones and the frontal processes of the maxilla, which constitute the upper third to half of the nose. The thickness of the bones varies, with the thickest portion just above the level of the canthus. As a result, osteotomies are rarely indicated above this level.

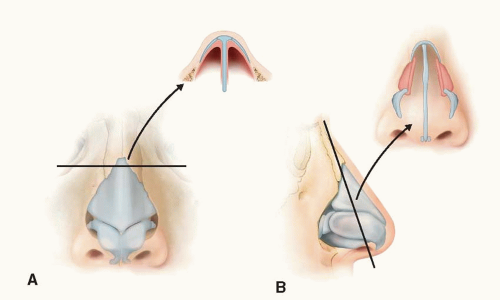

The upper cartilaginous framework, or midvault, is comprised of the paired upper lateral cartilages (ULCs) and dorsal cartilaginous septum. It begins at the “keystone” area, where the nasal bones overlap the ULCs. Normally, this is the widest part of the dorsum and resembles a “T” shape in cross section (Figures 48.2 A and B).

The inverted V deformity and/or disruption of the dorsal aesthetic lines may occur if the midvault area is overresected during the dorsal hump reduction. A component dorsal hump reduction is advised to avoid these complications.

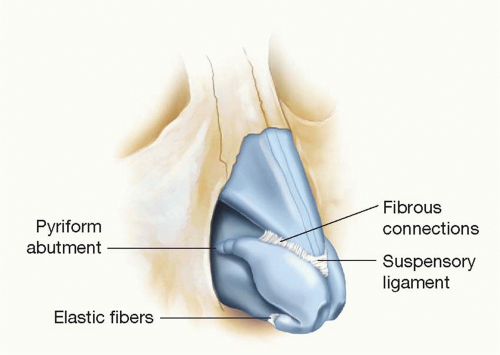

The lower cartilaginous framework is composed of the medial, middle, and lateral crura and begins where the lower lateral cartilages (LLCs) overlap the ULCs in what is called the “scroll” area. The tip cartilages are connected to each other, the ULCs, and the septum by fibrous tissue and ligaments (Figure 48.3). Disruption of these ligaments during rhinoplasty can result in diminished tip projection, requiring additional maneuvers to maintain or increase tip support.

Nasal Function

The functions of the nose, specifically respiration, humidification, filtration, temperature regulation, and protection, are regulated by the septum, turbinates, and nasal valves (internal and external).11

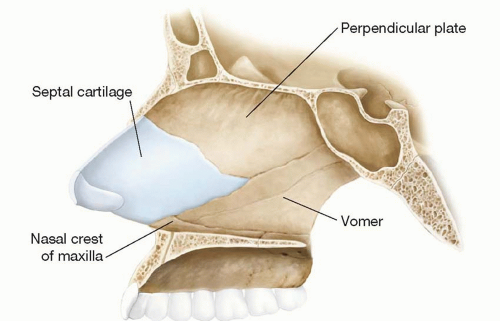

The constituents of the septum include the septal cartilage, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, the nasal crest of the maxilla, and the vomer (Figure 48.4). Laminar airflow is altered by septal deformities and can lead to secondary turbinate hypertrophy.12,13,14,15 It is paramount to analyze and address all portions of the septum when attempting to correct septal deformities. Furthermore, it should be noted that the cribriform plate is contiguous with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, necessitating care when performing a resection of this structure to avoid potential severe consequences, such as anosmia, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, or ascending infection/meningitis.

The turbinates are mucosa-lined bony extensions of the lateral nasal walls. This mucosa undergoes cyclical expansion and contraction mediated by the autonomic nervous system. The function of the turbinates is to assist in the transport of air during respiration and to condition/humidify inspired and expired air. The inferior turbinate, especially its most anterior portion, has the greatest impact on airway resistance, providing up to two-thirds of the total airway resistance.11 Turbinate pathology is frequently addressed via submucosal resection and/or outfracture techniques.16,17 However, overresection can lead to adverse effects on regulatory and physiologic functions, causing crust formation, bleeding, and nasal cilia dysfunction.

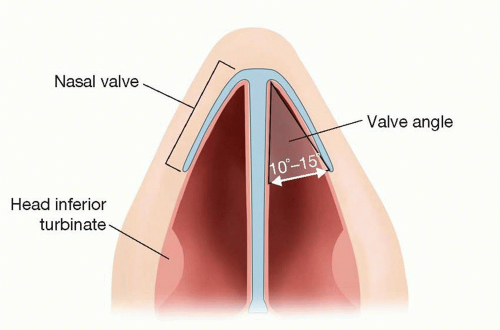

The internal nasal valve is the angle formed by the junction of the nasal septum and the caudal margin of the ULC and is usually 10° to 15° (Figure 48.5). It can be responsible for up to 50% of the total airway resistance and is the narrowest segment of the nasal airway.11 Occasionally, the head (anteriormost portion) of the inferior turbinate can be hypertrophied enough to cause further diminution of the cross-sectional area of this region. A positive Cottle’s sign (lateral traction on the cheek leading to increased airflow) signals collapse of the nasal valves and may indicate the need for spreader grafts to increase the valve angle and stent the airway open.

The external nasal valve is caudal to the internal valve and is the vestibule that serves as the entrance to the nose. This valve may be obstructed by extrinsic factors, such as foreign bodies, or intrinsic factors, such as weak or collapsed LLCs, loss of vestibular skin, or cicatricial narrowing. There are many options to correct these problems, including cartilage grafting (e.g., alar contour grafts,18 alar batten grafts,19 or lateral crural strut grafts20) or flaps (e.g., lower lateral crural turnover flap21), soft-tissue grafting (e.g., mucosal, skin, or composite grafts), lysis of adhesions/synechiae, or scar revision.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

The Initial Consultation

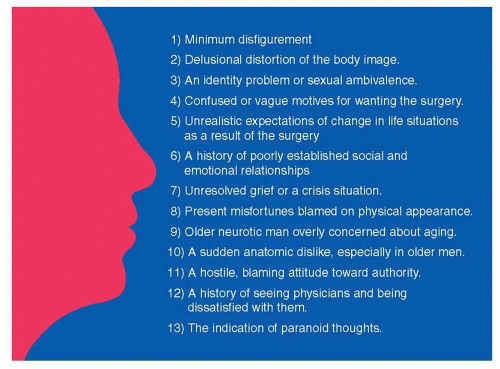

The patient’s concerns and levels of expectation must be assessed prior to any operative intervention. “Danger signs” have been described that may indicate that the patient has underlying psychological issues (Figure 48.6).22,23,24 Patients that fit these criteria are approached with caution, as surgical intervention may not be in either the patient’s or the surgeon’s best interest.

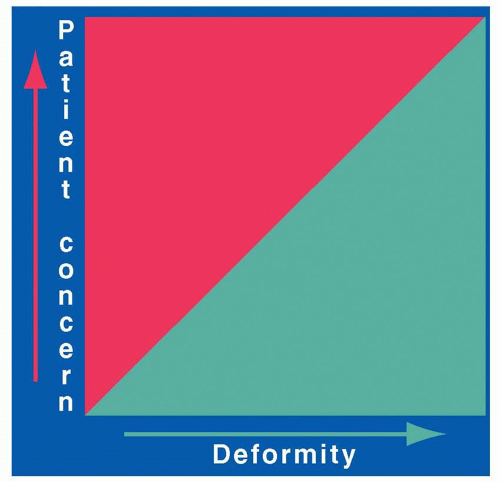

Patients are appropriate surgical candidates if their concern is proportionate to the degree of their deformity (green area; Figure 48.7). However, there are some patients with a degree of concern that is disproportionate to their deformity (red area). These patients frequently have unrealistic expectations that cannot be met regardless of the aesthetic improvement. It is best to avoid operating on these patients. Furthermore, regardless of the degree of deformity, if the skill level and expertise required to perform the rhinoplasty exceeds one’s ability, that patient should be referred to another surgeon who possesses the required proficiency.

Computer imaging has proven to be a useful tool to provide the patient with a visual understanding of the anticipated outcome, although the images are not meant to guarantee surgical results.25,26 These images, combined with standardized anterior, oblique, lateral, and basal photographs, serve as helpful adjuncts in the planning of the operation.

Nasofacial Analysis

Accurate, systematic, and thorough nasofacial analysis is performed to determine the subsequent operative plan. The nose must be examined not only in isolation but also in the context of the whole face so that the procedure preserves the overall facial balance and harmony. It is also necessary to evaluate the patient preoperatively for any natural facial asymmetries so that the patient gains a better understanding of exactly what was present before any operative intervention.

The skin type, thickness, and texture are evaluated. As mentioned, thicker, more sebaceous skin will require more aggressive modification of the underlying osseocartilaginous framework as changes tend to be camouflaged. Thinner skin will tend to show even minor changes.

The nasofacial analysis then proceeds in a systematic, methodical fashion (Table 48.1).1 Below are some of the routine relationships and proportions that are used when analyzing the rhinoplasty patient. While derived from Caucasian females, they can be modified depending on the ethnicity and gender of the patient.4,5,6,27,28 It is important to remember that these proportions are only general guidelines. Each nose is individualized to the patient in order to achieve optimal nasofacial balance and harmony.