Retinoids: Introduction

|

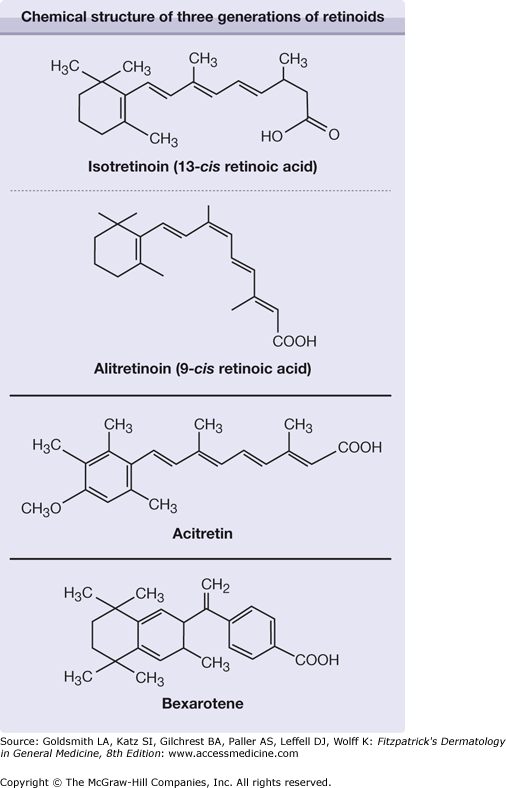

Retinoids include both naturally occurring molecules and synthetic compounds that have specific biologic activities that resemble those of vitamin A or bind to the nuclear receptors for retinoids. Vitamin A from natural sources was already being used in the 1930s in high dosages to treat certain hyperkeratotic diseases, often with toxic side effects. Three generations of synthetic retinoids have since been developed (Fig. 228-1).

First generation: All-trans–retinoic acid (tretinoin, ATRA), a naturally occurring metabolite of retinol, was the first retinoid synthesized but had no significant advantages over vitamin A in treatment of dermatologic diseases. It is used as a differentiation-inducing agent to treat acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Isotretinoin (13-cis–retinoic acid), clinically available since the 1970s, was found to cause prolonged remissions in patients with previously treatment-resistant cystic acne [it has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication since 1982].1

The latest approved systemic retinoid is alitretinoin (9-cis–retinoic acid), which is approved in several European countries and Canada for treatment of chronic hand eczema.

Second generation: Through replacement of the β-ionone ring in ATRA with an aromatic structure, newer retinoids with better therapeutic margins were synthesized in the 1970s. Etretinate and its free acid metabolite, acitretin, showed a therapeutic index ten times more favorable than that of ATRA. Etretinate (approved in Europe 1983 and by the FDA in 1987) and acitretin (approved 1987 and 1997, respectively) became a standard treatment for psoriasis. Acitretin has replaced etretinate in most countries, but not in Japan and a few other countries.

Third generation: The discovery of retinoic acid receptors (RARs)2,3 allowed research directed toward receptor-specific, third-generation retinoids with a safer therapeutic index and a more selective action. Bexarotene, approved by the FDA in 1999 for systemic use in treating cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), is a prime example. Bexarotene belongs to a subclass of arotinoids called rexinoids, because they bind to the retinoid X receptors (see Section “Bexarotene”).

Mechanism of Action

Retinoids affect cell growth and differentiation, exert immunomodulatory action, and alter cellular adhesiveness.4 Their effect on RARs is discussed in detail in Chapter 217.

Under normal conditions, virtually all effects of vitamin A in the skin are mediated by ATRA, the cellular level of which is meticulously controlled. Endogenous ATRA has been at the focus in the development of a new class of compounds called retinoic acid metabolism-blocking agents, which are basically cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme 26 inhibitors that impede the oxidative degradation of ATRA and thus increase the retinoid activity in target tissues.5 Two such drugs (liarozole and rambazole) are under development and are not yet on the market.

Pharmacokinetics

Isotretinoin, alitretionin, acitretin/etretinate, and bexarotene differ not only in their spectra of clinical efficacy but also in their toxicities and pharmacokinetics. Due to their lipophilicity, the oral bioavailability of all retinoids is markedly enhanced when they are administrated with food, especially with fatty meals. Retinoids are metabolized mainly by oxidation and chain shortening to biologically inactive and hydrophilic metabolites, which facilitates biliary and/or renal elimination. The oxidative metabolism is induced primarily by the retinoids themselves and other agents that induce hepatic CYP isoforms.6

Isotretinoin, alitretinoin, and ATRA are three partially interconvertible isomers that differ in their elimination half-lives—approximately 20 hours for isotretinoin and 1 hour for ATRA. Isotretinoin undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver and subsequent enterohepatic recycling. In plasma, isotretinoin is more than 99% bound to plasma protein, mainly albumin. It is stored in neither the liver nor adipose tissue, in sharp contrast to vitamin A and etretinate. The major metabolite is 4-oxoisotretinoin, which has reduced bioactivity; both compounds are excreted in urine and feces. After the end of treatment, endogenous concentrations of isotretinoin and its major metabolite are reached within 2 weeks. Therefore, a 1-month post-therapy period of contraception provides an adequate safety margin.7 No clear affinity for any RARs has been identified with isotretinoin, whereas ATRA binds to RARs and alitretinoin uniquely binds to both RARs and RXRs.

Etretinate is a prodrug of acitretin that undergoes extensive hydrolysis in the body to yield the corresponding acid metabolite. In animal studies and in clinical studies in patients with severe keratinizing disorders, acitretin is as effective as etretinate.8 However, acitretin has a great pharmacokinetic advantage because it is eliminated more rapidly than etretinate.9 Etretinate is approximately 50 times more lipophilic than acitretin and binds strongly to plasma lipoproteins, whereas acitretin binds to albumin. This fact has a profound influence on the respective pharmacokinetic properties of the two drugs.

Even when etretinate and acitretin are taken with food, the absorption of the two drugs varies.10 Etretinate is stored in adipose tissue from which it is released slowly; it has a terminal half-life of up to 120 days. In contrast, acitretin has an elimination half-life of only 2 days.9 However, small amounts of etretinate can be formed in patients receiving acitretin if it is taken simultaneously with alcohol.11 This has prompted the manufacturer to extend the time of compulsory contraception in patients taking acitretin to 2 years (3 years in the United States).12 Acitretin still has a pharmacokinetic advantage over etretinate; however, all women must strictly avoid alcohol consumption during treatment and for 2 months thereafter.9

Acitretin metabolism primarily involves isomerization instead of oxidation. The major metabolite of acitretin is its 13-cis-isomer, which is inactive. Paradoxically, acitretin activates all three RAR subtypes but binds poorly to them.13

Bexarotene is approximately 100-fold more potent in activating retinoid X receptors than RARs. Its absorption is particularly increased by taking it with fatty meals. In plasma, bexarotene is highly bound (more than 99%) to proteins that have not yet been characterized, and the ability of bexarotene to displace drugs bound to plasma proteins and the ability of drugs to displace bexarotene is unknown. Bexarotene probably has a clearance profile similar to that of isotretinoin with a terminal half-life of between 7 and 9 hours.14 Bexarotene is metabolized by CYP 3A4 and generates its own inactive oxidative metabolites via hepatic CYP 3A4 induction. Neither bexarotene nor its metabolites are excreted in urine; elimination is thought to occur primarily via the hepatobiliary system.15

Indications

Isotretinoin is remarkably effective in curing acne, possibly because it affects—primarily or secondarily—all etiologic factors implicated in the pathogenesis of acne: sebum production, comedogenesis, and colonization with Propionibacterium acnes.16 Of all the natural and synthetic retinoids used in humans, only isotretinoin suppresses sebum excretion and reduces sebaceous gland size.

In the early 1980s, isotretinoin treatment was restricted to patients with severe nodulocystic acne. With increasing experience, however, its use has been extended to patients with less severe disease who respond unsatisfactorily to conventional therapies such as long-term antibiotics because of the increased resistance of P. acnes to many antibiotics.17,18

The retinoid of first choice for oral treatment of psoriasis is acitretin. Acitretin appears to be as effective as etretinate and can be used in the same combination regimens.19–23 The best results have been obtained in pustular psoriasis of the palmoplantar or generalized (von Zumbusch) type.19,24,25 Rebound does not usually occur after treatment is stopped, and reintroduction of the drug when it does occur produces a beneficial response.26 Although complete clearing of plaque-type psoriasis is achieved in only approximately 30% of treated patients, significant improvement is obtained in a further 50%.5,27,28 The decrease in the psoriasis area and severity index is approximately 60%–70%, depending on the dosage.5,8 Approximately 20% of patients may be considered to experience treatment failures. Combination of acitretin with other antipsoriatic agents may then be required (see Section “Dosing Regimens”).

In a 20-week treatment study,29 six of eleven patients (54%) with HIV infection who had psoriasis showed good-to-excellent responses to acitretin monotherapy (75 mg/day). Both skin and joint manifestations responded to acitretin therapy in most patients. The adverse effects were moderate and well tolerated, and measures of immune parameters did not indicate exacerbation of immunosuppression in most patients.

Isotretinoin has less effect on psoriasis than acitretin or etretinate, although some efficacy has been shown in combination with psoralen plus ultraviolet A light (PUVA) therapy.12 Nevertheless, some dermatologists use isotretinoin to treat women with psoriasis who need systemic retinoids to avoid the long postacitretin contraception period required.

Alitretinoin was recently approved in several European countries and in Canada for treatment-resistant chronic hand eczema. Between 3 and 6 months of therapy is usually required to fully appreciate the effect.30

Acitretin and etretinate have been used for many years “off-lable” to treat hyperkeratotic (tylotic) hand and foot eczema.

In 1999, the FDA approved bexarotene as oral therapy for the treatment of CTCL that is refractory to at least one systemic therapy. In early (IA-IIA) and advanced (IIB-IVB) stages of CTCL (see Chapter 145), oral bexarotene monotherapy produced approximately 60% and 50% response rates, respectively, at a dosage of 300 mg/m2 or more per day within the first 2 months in most patients.32,33

Older studies showed that etretinate may induce clinical improvement in patients with CTCL (e.g., mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome) with no internal involvement; better results were obtained when etretinate was combined with PUVA treatment or interferon-α therapy. Use of the combination of acitretin or isotretinoin with oral vitamin D3 (calcitriol) to obtain synergistic effects in the treatment of CTCL has been reported.31

Multiple other skin disorders respond to retinoids, but for only a few of them is the effect established in controlled studies.34 In many reports the choice of etretinate/acitretin rather than isotretinoin was based not on pharmacologic considerations but on availability of the product. Bexarotene and alitretinoin have not been tested extensively for indications other than CTCL and hand eczema, respectively.

Among the different types of ichthyosis, the best results are obtained with acitretin for autosomal recessive congenital ichthyoses such as lamellar ichthyosis. Treatment of epidermolytic ichthyosis (bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma) may lead to an initial increase in bullae. Good results also have been achieved in treating recessive X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, and palmoplantar keratoderma; if they are of limited severity, these diseases often do not require retinoid therapy (see Chapters 49 and 50).

Moderate-to-severe forms of Darier disease (Darier-White disease) are good indications for retinoid therapy. Care should be taken to initiate therapy with a low dosage, such as 10 mg/day of acitretin, to prevent initial exacerbation of the disease; usually 20 mg/day is sufficient for significant improvement. Long-term treatment is usually needed to prevent relapse. Low-dose isotretinoin therapy has been used especially in women with Darier disease. Combination of retinoids with antibiotics may enhance the clinical effects, because skin lesions are frequently infected (see Chapter 51).

Early treatment with retinoids appears to offer the best chance for clearing of pityriasis rubra pilaris. In extensive cases, concomitant use of methotrexate may be advantageous, but this combination carries an increased risk for toxicity. Etretinate is considered to be superior to isotretinoin in the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris (see Chapter 24).35

In severe forms or in treatment-resistant rosacea, isotretinoin therapy may be more effective for inflammatory lesions than for vascular lesions.36 A low daily dose (10 mg) is often sufficient. The best indications are severe cases of rosacea associated with significant seborrhea (see Chapter 81).

Isotretinoin has limited effect on hidradenitis suppurativa, but some investigators recommend this therapy during the weeks or months preceding surgical treatment. Prolonged therapy with acitretin/etretinate has been used with some success, especially in treating extensive, inflammatory lesions unsuitable for surgery (see Chapter 85).37,38

Etretinate and acitretin are effective in the treatment of premalignant skin lesions, including human papillomavirus-induced tumors and actinic keratoses. In basal cell nevus syndrome and in xeroderma pigmentosum, these drugs reduce dramatically the incidence of malignant degeneration of the skin lesions. A double-blind study demonstrated that acitretin at a dosage of 30 mg/day for 6 months prevented the development of premalignant and malignant skin lesions in renal transplant recipients (see Chapters 113, 114, 115 and 116.)39

Acitretin/etretinate is an effective treatment for severe lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of the vulva and may be recommended intermittently for patients who are intolerant of or resistant to local therapies (see Chapter 65).40

Both isotretinoin and acitretin have been used successfully in patients with various forms of lupus erythematosus. However, the lesions recur after completion of treatment as quickly as the initial improvement appeared. Acitretin and hydroxychloroquine are equally effective in the treatment of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 155).12

Dosing Regimens

Drug | Indication | Initially | Sustained | Length of Therapy (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Isotretinoin | Acne | 0.3–0.5 | 0.5–1.0 | 4–6 |

Acitretin | Psoriasis DOKa | 0.2–0.5 0.3–0.6 | 0.3–0.8 0.5–1.0 | >3 >3 |

Alitretinoin | hand eczema | 10–30b | 210–30b | >6 |