Completeness of amputation: It is important to separate complete (total) amputations from incomplete (subtotal/near-total) amputations, which separates replantations from revascularizations. A revascularization may appear to be an easier operation compared with replantation; however, in practice it is often more difficult. The presence of intact bone in an incomplete amputation means that the surgeon may not be able to shorten the bone significantly, which, in turn, may necessitate the use of vein grafts, nerve grafts, or skin flaps to bridge any defects. It is also not possible to do examine the part on the back table to isolate the neurovascular structures.

Anatomical level: Upper extremity amputations are classified into two broad groups.

Amputations proximal to the radiocarpal joint: Replantation at this level is termed a major limb replantation because these replantations have a higher risk of systemic complications. Because muscle can withstand ischemia for a short period of time, there is a risk of myoglobinuria and renal failure. The more proximal the amputation, the greater the muscle mass. Systemic complications are directly related to the muscle mass and the ischemia time and therefore the success of a major limb replantation depends on establishing circulation early.

Amputations distal to the radiocarpal joint: These amputations are described based on the flexor tendon zones of injury (zones 1-4). Each zone has anatomic characteristics that influence the technique and outcome of replantation.

Mechanism of injury: An amputation can occur following a clean-cut, a crush, an avulsion, or any combination of these injury patterns. Survival, as well as late functional outcome, depends to a great extent on the mechanism of injury. Although a clean-cut amputation or a pure avulsion type injury is easily identified, crush injuries vary widely. We have modified the classification of injury mechanism proposed by Yamano to simplify it and eliminate the subjectivity involved in grading crush amputations.

Clean cut (sharp cut/guillotine): Results from objects with narrow sharp edges like knives or meat slicers. The wound edges are clean and minimal debridement is required.

Blunt cut (dull cut): Results from objects with narrow blunt edges like saws or fan blades. The wound edges are jagged and show crushing, which extends a limited distance proximal and/or distal to the amputation. Moderate debridement is required.

Crush: Results from an object with a broad blunt edge, like a punch press or a wooden log. The wound is torn (lacerated) rather than cut (incised) and the wound edges are irregular. There is significant tissue injury that extends proximal and/or distal to the amputation. Extensive debridement is required.

Avulsion: Caused by traction, such as an anchor rope or the reins of a horse. Similar to a crush injury, the tissue is torn rather than cut. However, unlike crush where the tissue injury is at the level of the crush, the separation of tissues (vessels, nerve, tendon, bone, and skin) occurs at different levels depending on their tensile strength. A degloving injury is a special type of avulsion amputation usually caused by a tight ring (ring avulsion amputation), which gets caught during motion. The skeletal and tendinous apparatus are preserved, whereas the surrounding soft tissue envelope is pulled off. Peripheral bony parts of varying lengths may be avulsed together with the tissue covering.

Combined: Caused by a combination of crush, avulsion, or other mechanisms of injury. An example is an initial incomplete crush amputation by a machine followed by an avulsion when the patient reflexively with-draws the hand resulting in a complete amputation.

Transfer to a replantation center: The outcome of replantation depends on (1) patient factors; (2) the nature of the injury; and (3) the skill and experience of the surgical team. The first two cannot be controlled. Therefore, it is important that an experienced microsurgeon ascertains the suitability for replantation. All patients deserve such an evaluation and should be expeditiously referred to appropriate centers, where they can be guided toward decisions that serve their best interests. Before transport, an attempt should be made to contact the center to determine the appropriateness of the transfer and to allow preparation for replantation. A detailed description of the injury, the patient’s age, and general health, and the condition of the injured part are provided to the replant team over the phone. A digital photograph of the injured part helps tremendously.

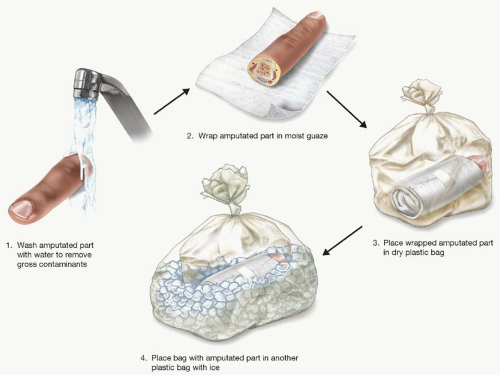

The amputation stump is covered with a saline-moistened gauze, loosely wrapped, and elevated. Compression bandages may be required to stop bleeding. Once the patient is stabilized, an attempt is made to collect and preserve all amputated parts. The amputated part/s are wrapped in a saline-moistened gauze and then placed in a dry, watertight, plastic bag, that is in turn placed on ice (Figure 83.1). The aim is to keep the part cold to prevent the ill effects of warm ischemia, while avoiding direct tissue contact with ice that can cause frostbite. In cases of incomplete, nonviable amputations, the wound is wrapped in moist gauze, dressed, a simple splint applied to prevent kinking, and ice packs used to surround the distal portion of the amputated part. Radiography and arteriography delay transfer, increase the total ischemia time, and can be expeditiously performed at the replantation center.

Management in the emergency department: Once the patient arrives at the replantation center, the patient is

examined to rule out associated injuries. This is especially important in major replantations, where the attention is focused on the amputation and there is real risk of missing severe injuries. Resuscitation and stabilization of the patient should take precedence over treatment of the amputated limb. A member of the replantation team obtains a brief history from the patient and the patient’s family that includes the age, hand dominance, occupation, preexisting systemic illness, allergies, and the mechanism of injury. History of smoking, alcohol or drug dependence, and any psychiatric illness should also be obtained. Radiographs of the amputated part and the proximal extremity are obtained. Routine investigations include a chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, complete blood count, serum electrolytes, and blood typing and cross matching.

TABLE 83.1 INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR REPLANTATION

▪

INDICATIONS

▪

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patient factors

All pediatric amputations

Age > 70 y

Patient desire (aesthetic/social)

High risk of surgery (severe systemic illness)

E.g., Small finger replantation in Japan, ring avulsion amputation in young lady

Active psychiatric illness (self-amputation)

Smoker

Drug abuse

Injury characteristics

Thumb

Associated life-threatening injuries

Multiple fingers

Multiple level amputation

Mid-palm/wrist/major amputation

Extreme contamination

Single finger zone I amputation

Severe avulsion or crush

Duration of warm ischemia ([all equal to]level of amputation)

Single finger zone II amputation

Active bleeding may be found, especially in incomplete amputations with partial vessel lacerations. Control of bleeding is usually achieved by a pressure dressing. Blind attempts at clamping or ligation of vessels are avoided to prevent further injury to vessels and nerves. Temporary use of a proximal tourniquet is preferable, precisely identifying the bleeder, and clamping or ligating it carefully. Patients are given tetanus prophylaxis if the immunization status is uncertain or if the last shot was received more than 5 years previously. Prophylactic antibiotics with first-generation cephalosporins are indicated in amputation injuries directed toward the most likely organism, Staphylococcus aureus. An aminoglycoside and/or a third-generation cephalosporin may be required in amputations associated with more extensive contamination.

Evaluation for replantation (indications/contraindications): In complete amputations, a member of the replant team should take the amputated part to the operating room as soon as possible, to do preliminary bench-work assessing the suitability for replantation and to dissect, isolate, and tag important structures. This is ideally done while the patient is being stabilized in the emergency department. This may also be possible in incomplete amputations in which the amputated part is held by strands of tissue that have no contribution to circulation or innervation. The surgeon can divide the remaining strands of tissue converting an incomplete amputation into a complete amputation. When there is a skin bridge that may be important for venous drainage, however, keeping the skin bridge is important to avoid the most difficult part of the operation, the venous repair.

Patients desire reattachment of every amputated part, but they are not aware of the risk, cost, and eventual outcome. Although the indications and contraindications (Table 83.1) for replantation have remained more or less unchanged over many years, the decision to replant or not to replant is individualized. The main concern is “how to make it functional.” Function encompasses all aspects of a person’s performance in society, aesthetic as well as mechanical. Prior to replantation, a frank discussion between the patient (and relatives) and the surgeon is mandatory to discuss the likelihood of a successful result, the duration of postoperative therapy, possible need for multiple secondary surgeries, estimated time away from employment, and to temper patient expectations. The expected outcomes for digital replantation are shown in Table 83.2. The guidelines for replantation suggested by Schlenker and Koulis are useful in decision making, especially in borderline cases (Table 83.3). The long duration of surgery; need for blood transfusions; need for joint fusion; possible use of skin, nerve, and vein grafts; and approximate length of hospitalization are emphasized. Rarely, a flap may be required in the primary setting to cover exposed vessels, and appropriate options are planned and discussed with the patient preoperatively.

Team approach: Once a decision to replant a part has been made, events should progress in an efficient, stepwise manner. Replantation surgery takes a long time, such as 6 to 8 hours for a major limb replantation and 2 to 5 hours for a more distal amputation. In multiple digital amputations, each digit can take up to 3 to 4 hours. A team approach is advised to avoid surgeon fatigue. Realistically, in most centers, one surgeon is on call for replantation and a backup surgeon is often not available. It is important in multiple digit replantations, therefore, to proceed efficiently; fatigue

will set in after a few hours of intense activities under the microscope. Ideally, two teams each consisting of a surgeon trained in microsurgery and hand surgery should be available for these procedures. One team can work on the amputated part, while the other prepares the stump. The operating nurses should also have training in the handling of microsurgical instruments and microsutures. We have found it useful to connect a television monitor to the operating microscope. This allows the nurses to see what is happening and improves their participation in what could otherwise be a long and tedious procedure for them.

TABLE 83.2 EXPECTED OUTCOMES OF DIGITAL REPLANTATION

• 15-50% replant failure rate

• 50% of patients require a blood transfusion

• 10 days average hospital stay

• Cost of replantation is 10-15 times that of revision amputation

• 36-77% chance of having only protective sensation

• Motion in replanted fingers averages 50% of normal

• 60% of patients needs additional surgery (average 2.5 procedures)

• 7 mo average time off work

Adapted from Rinker B, Vasconez HC, Mentzer Jr RM. Replantation: Past, present, and future. J Kentucky Medical Association 2004;102:247-253

II. Anesthesia: Regional anesthesia alone or in combination with general anesthesia provides the benefit of sympathetic blockade that results in vasodilatation and facilitates vascular anastomosis. The regional block can also be maintained in the postoperative period.

Patient preparation: A urinary catheter is inserted because of the length of the procedure. A padded tourniquet is applied around the upper arm for all amputations except transhumeral. In major limb replantation, a tourniquet is placed on the lower limb which is prepared for the skin, nerve, and/or vein grafts. The operating room and the patient are kept warm and appropriate padding provided at bony pressure points.

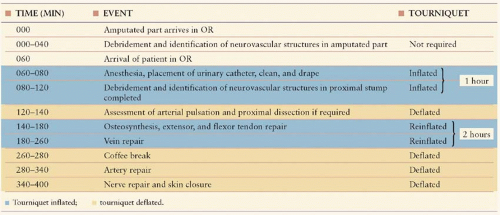

Sequence of steps: The logical sequence is to progress from repair of the deeper structures (bone and tendon) to superficial structures (nerve and vessels) and from repairs requiring gross manipulation (bone and tendon) to those that need an operating microscope (nerve and vessels) for fine precise repairs. The exact order of repair depends on surgeon preference and the level of amputation. There is some disagreement whether arterial or venous repair should be done first. Our preference is to establish venous drainage first. This minimizes blood loss and completes what is technically the most difficult step of replantation early on. Doing the artery first allows selection of veins with good outflow for anastomosis; however, the field is bloody and dissection difficult. Reinflating the tourniquet at this stage may increase the risk of arterial thrombosis as a result of stasis across the anastomosis. The two situations when it is preferable to do the arterial repair first are a distal replant where the arterial inflow helps in identifying the veins and in major limb replantations to decrease the warm ischemia time. A timeline sequence of steps has been depicted in Table 83.4.

TABLE 83.3 GUIDELINES FOR REPLANTATION

▪

PATIENT FACTORS

▪

INJURY CHARACTERISTICS

Age (y)

Score

Type of injury

Score

00-40

0

Clean cut

0

40-50

1

Blunt cut

1

50-60

3

Crush

3

60-70

5

Avulsion

3

>70

7

Combined

5

ASAa physical status class

Score

Warm ischemia time (h)

Score

I (Healthy patient)

0

0-4

0

II (Mild systemic disease, no functional limitation)

1

4-6

3

III (Severe systemic disease, definite functional limitation, but not incapacitating)

3

6-8

5

IV (Incapacitating systemic disease that is a constant threat to life)

7

>8

7

a ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

The authors are reluctant to undertake replantation when the score is 7 or more.

The scoring system does not take into account relative importance of thumb over single finger nor the level of amputation.

Adapted from Schlenker JD, Koulis CP. Amputations and replantations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1993;11(3):739-753.

Bench-work: The amputated part is cleaned with routine bacteriocidal solution such as betadine and placed on a small operating table. In the hand, wrist, and major limb replants, the debridement and dissection of the neurovascular structures are performed with the amputated part on an ice pack (avoiding direct contact with ice) to limit the warm ischemia time. When one digit in a multiple digit injury is being dissected, the other digits are preserved as previously mentioned. Cooling should continue until the arterial anastomosis is complete. Amputated parts or digits unsuitable for replantation should not be discarded, but evaluated for use as a spare part or as a source of nerve, arterial, skin, or bone graft. Irrespective of the level of amputation, the key steps in preparation of the amputated part include meticulous debridement, isolation of the neurovascular structures, and bone shortening.

All grossly contaminated or devitalized tissues are sharply debrided. Ragged bone and the flexor and extensor tendon ends are trimmed. A mid-lateral incision is made on both sides. The digital neurovascular bundles are isolated and tagged. The digital arteries are inspected carefully under loupe magnification or the microscope. Damaged arteries often show separation of the endothelial layer. Stretched or traumatized vessels are frequently speckled due to rupture of the vasa vasorum producing the “measles” or “paprika” sign. A corkscrew appearance of the arteries (ribbon sign) suggests an avulsion force (Figure 83.2A). Vessels should be trimmed until normal appearing vessel ends are present. Bruising of the skin along the course of the digit (red line sign) suggests a severe avulsion injury with disruption of branches of the digital artery at the site of the bruises (Figure 83.2B). Replantation may not be successful in these cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree