Reduction Mammaplasty Using the Central Mound Technique

Daniel P. Luppens

Mark A. Codner

Introduction

The central mound technique differs fundamentally from most popular techniques of breast reduction in that it relies predominately on a broad-based glandular blood supply to the nipple. The central mound technique involves separating the skin from the gland of the breast, resecting the desired portion of gland, and resecting a customized pattern of skin to achieve the desired result. Rather than rely on the skin resection only or gland resection only for the final breast shape, the central mound technique relies on the interaction of the gland with the remaining skin envelope. Additional advantages to the central mound reduction include simple preoperative markings, no limitations due to breast size or ptosis, preservation of nipple sensitivity and the potential to breast-feed, and excellent aesthetic results with a minimal secondary revisions.

The central mound approach to breast reduction surgery was introduced by Hester in 1985 (1,2). Hester’s technique is a modification of earlier methods of achieving breast reduction by separating the skin from the gland. In 1921, Biesenberger described a technique of separation of the skin from the gland, leaving the nipple and areola attached, followed by resection of the lateral half of the breast. The remaining gland was then sutured to create a cone and the skin redraped over the new breast contour. Biesenberger’s technique threatened the blood supply to the nipple because of extensive lateral dissection and the 180-deg glandular rotation performed during shaping (3,4). In order to better preserve blood supply to the nipple, early modifications to the technique were made by a number of surgeons, including Schwarzmann, Gillies, and McIndoe (5,6,7,8,9).

Unlike some previous modifications, the central mound technique has a firm anatomic basis explaining the adequate blood supply to both skin flaps and the gland of the breast. The principles of this reliable technique depend on the blood supply from the lateral thoracic artery, intercostal perforators, and internal mammary perforators through the pectoralis major muscle. The skin and subcutaneous flaps are elevated off the gland, which allows the breast mound to be reduced and shaped according to the surgeon’s desire. The nipple remains at the apex of the gland, which can be reduced and sculpted like a breast implant, preserving a broad blood supply from the chest wall. After the desired breast volume is obtained by sculpting the gland, the skin and subcutaneous flaps are then closed around the reduced gland as a well-fitting “brassiere” to support and further refine the final size and shape of the breast. Breast projection can be customized independent of preoperative patterns and glandular resection. The technique has proven in clinical experience to be reliable and versatile and can be used similarly as a technique for mastopexy. The central mound technique has been used for nearly 20 years with reliable and reproducible results.

Anatomy

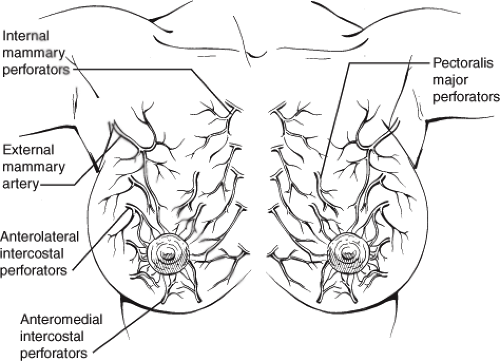

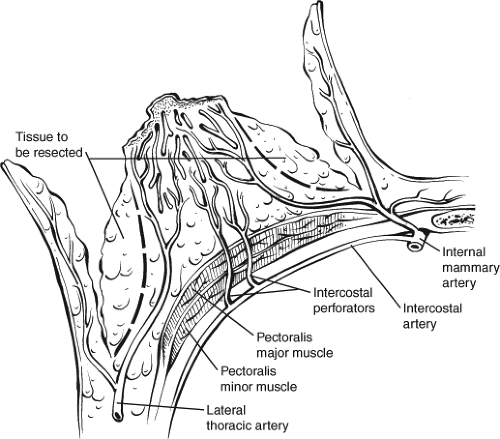

Consideration of the blood supply to the breast is important to maximize blood supply to both the gland and the skin flaps. The blood supply to the breast includes branches from the lateral thoracic and thoracoacromial arteries, as well as pectoralis major perforators supplied by the anterolateral intercostal perforators, anteromedial intercostal perforators, and the internal mammary perforators (Fig. 96.1). The central mound technique exposes the breast gland following elevation of thick skin and subcutaneous dermoglandular flaps. The lateral and medial skin flaps also have a robust blood supply from the lateral thoracic and internal mammary perforators, respectively (Fig. 96.2). The skin flaps should not be too thin or elevated down to the chest wall in order to preserve blood supply at the base of the glandular pedicle. Instead, a layer of breast and adipose tissue measuring a thickness of 3 to 4 cm is preserved over the thoracic fascia to prevent division of the vessels and sensory nerves. The primary sensory nerve to the nipple is the lateral cutaneous branch of the fourth thoracic nerve, which enters the breast along the lateral border. Once the breast mound is exposed, the excess gland is resected in a tangential fashion (10).

Technique

Compared to the markings of some other techniques of breast reduction that often commit the surgeon to a pattern that can result in a shortage of skin during closure, the markings for the central mound reduction are quite simple. With the patient in the upright position, the initial mark should be made at the sternal notch. The second point is marked at the approximate level of the inframammary fold transposed to the anterior aspect of the breast in the central meridian. Although a number of techniques have been described to localize this point, it is approximately 21 cm from the sternal notch, with the excess weight taken off the breast. If the breast is not supported to reduce the excess weight, this point will retract superiorly once reduction has taken place, resulting in a nipple that is too superiorly positioned. This mark will approximate the new level of the superior aspect of the areola, which will place the nipple at 23 cm from the sternal notch. Anticipated changes in breast shape following all reduction techniques include “bottoming out” or glandular ptosis. As ptosis recurs, the distance from the inferior aspect of the areola to the inframammary fold increases. Placing the nipple slightly lower on the breast mound has been found to maintain a better aesthetic appearance as changes occur after surgery.

The inframammary fold is then marked, as well as a vertical line at the meridian of the breast at the lowest point of the

inframammary fold, which is approximately 11 cm from the midline. Excess adipose tissue at the axillary tail of Spence is circled to indicate the areas that require liposuction during the reduction. An inverted V is drawn from the mark at the apex of the new nipple-areola complex position to the width of the existing areola (Fig. 96.3). At this point, two parallel lines are drawn from the medial and lateral aspect of the areola inferiorly to the inframammary fold. Although this area represents the skin to be deepithelialized, the dermal pedicle does not contribute significantly to the blood supply of the nipple. Furthermore, some patients with a wide areola and minimal skin excess may have the maximal skin tension during closure just below the existing areola. Therefore, a modification of the marking may include a single incision from the inferior aspect of the areola to the inframammary fold to preserve skin for closure (Fig. 96.4).

inframammary fold, which is approximately 11 cm from the midline. Excess adipose tissue at the axillary tail of Spence is circled to indicate the areas that require liposuction during the reduction. An inverted V is drawn from the mark at the apex of the new nipple-areola complex position to the width of the existing areola (Fig. 96.3). At this point, two parallel lines are drawn from the medial and lateral aspect of the areola inferiorly to the inframammary fold. Although this area represents the skin to be deepithelialized, the dermal pedicle does not contribute significantly to the blood supply of the nipple. Furthermore, some patients with a wide areola and minimal skin excess may have the maximal skin tension during closure just below the existing areola. Therefore, a modification of the marking may include a single incision from the inferior aspect of the areola to the inframammary fold to preserve skin for closure (Fig. 96.4).

The patient should be prepped and draped with the arms properly secured to arm boards extended at right angles from the operating table. A nipple marker with a 42-mm diameter is used to mark the nipple while the assistant places the areola on a gentle stretch. Vigorous stretching of the areola during marking can result in tension on the areola during closure and can compromise the blood supply, resulting in peripheral areolar necrosis. A circular incision is made around the areola. Then the skin is deepithelialized above and below the areola within the preoperative markings down to the level of the inframammary fold (Fig. 96.5A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree