Reconstruction of the Eyelids, Correction of Ptosis, and Canthoplasty

Nicholas T. Haddock

The eyelids provide globe protection and preserve vision. In addition, variations in periorbital structures provide for identifiable differences in ethnicity, gender, and age and display characteristic signs of various emotional states. Reconstruction of the eyelid mandates consideration of both function and aesthetics. Anatomic considerations are vital in eyelid reconstruction, and eyelid anatomy is presented in detail in Chapter 46.

EYELID RECONSTRUCTION

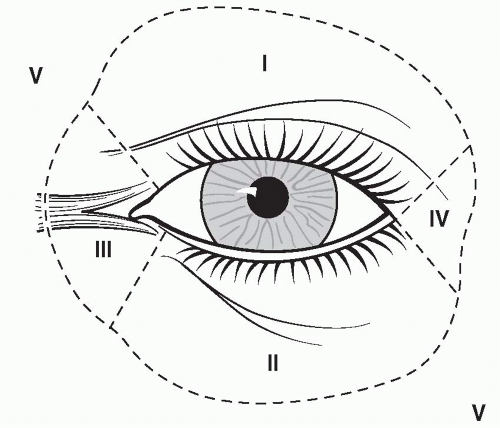

Periorbital defects can be congenital, traumatic, or ablative. Regardless of the etiology, reconstruction begins with an ophthalmologic examination and by analyzing the defect in terms of the location of the defect and the layers involved. Spinelli and Jelks divided this region into five zones–zone 1, the upper eyelid; zone 2, the lower eyelid; zone 3, the medial canthus; zone 4, the lateral canthus; and zone 5, the surrounding tissues (Figure 32.1).5 In addition, consideration is given to each layer that requires replacement. Typically, tissue grafts, local flaps, or a combination are required.

Tissue Grafts

Autologous tissue grafts are often required, either alone or in concert with a local flap. In full-thickness defects, either the anterior or posterior lamella must be reconstructed with a vascularized flap, providing a recipient site for a graft to reconstruct the other layer. An ideal donor site in anterior lamellar defects with a healthy wound bed is a full-thickness skin graft from the contralateral upper eyelid. When upper eyelid skin is limited, the retroauricular region or the supraclavicular region offers a secondary source. Fascia grafts, either from the deep temporal fascia or the tensor fascia lata, can be used to provide structural integrity for the eyelid or canthal regions. These can act as spacer grafts or can play a role in procedures for the treatment of upper eyelid ptosis. Cartilage grafts are typically used as a spacer or to replace the missing tarsal plate. Ear cartilage from the scapha most resembles the native tarsal plate, but thinned conchal grafts are a reasonable alternative. Nasal chondromucosa provides both a structural layer and the mucous membrane but has more potential donor site problems and is used infrequently. Resurfacing defects of the posterior lamella can only be accomplished with a tarsoconjunctival graft. Donor tissue is limited, however, and buccal or hard palate mucosal grafts are better options.2

FIGURE 32.1. Periorbital zones as described by Spinelli and Jelks.5 |

RECONSTRUCTION BY ZONE

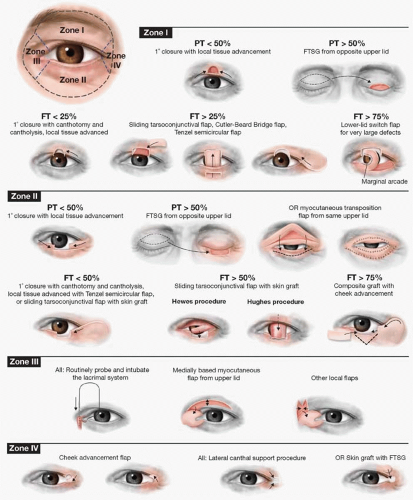

Periorbital reconstruction by zone is summarized in Figure 32.2.

Zone 1: Upper Eyelid Reconstruction

Proper repair of the upper eyelid is necessary for globe protection. Partial-thickness defects of the anterior lamallae are divided by size into those that are less than or greater than 50% of the horizontal lid dimension. For defects that are less than 50% of the lid, local tissue advancement and primary closure are performed. For defects larger than 50% of the lid length, a full-thickness skin graft is typically required.5 Incisions should be made in the natural lid crease if possible.

Treatment of full-thickness defects is also based on defect size. For defects of less than 25%, primary closure by converting the defect into a pentagonal shape can help avoid deformity.5 In youth, there is less eyelid laxity, and primary closure may not be possible in wounds greater than 20%. In elderly patients, whose lids have more laxity, defects up to 30% of the horizontal lid dimension may be closed primarily but may require a lateral canthotomy for a tension-free repair.2 Care should be taken to precisely approximate the lid margin. A layered closure is performed with attention to the alignment of the tarsal plates.

For defects greater than 25% but less than 75% of lid length, there are a number of reconstructive options. Most of these require a vascularized regional flap, which provides a recipient bed for a graft to separately reconstruct the anterior or posterior lamella. A sliding tarsoconjunctival flap borrows tissue from the uninjured portion of the ipsilateral upper eyelid. This flap is an option for posterior lamella defects involving the medial or lateral aspect of the upper eyelid. The inferior incision for this horizontally based flap is 4 mm above the lid margin and extends to create a flap that is equal to the defect size. The superior incision is designed to fit the defect, and a vertical relaxing incision is required in the tarsal plate to allow for advancement.2 A full-thickness skin graft is required for coverage of this flap to reconstruct the anterior lamella. In central wounds, a tarsoconjunctival flap can be developed from the lower eyelid as is done for lower eyelid reconstruction in the Hughes procedure.6 (See section “Zone 2: Lower Eyelid Reconstruction.”) This approach has the obvious disadvantage of a second procedure and obstruction of vision for the period prior to flap division.

The Cutler-Beard bridge flap is a full-thickness composite flap from the lower eyelid.7 A transverse full-thickness incision is made approximately 5 mm inferior to the lid margin in the lower eyelid, which allows flap elevation without compromising vascularity to the remaining lower eyelid. The horizontal width of the flap should match the width of the upper eyelid defect, and vertical full-thickness incisions are made to the inferior fornix at this width. The flap is advanced posterior to the remaining lid margin and secured into the upper eyelid defect with a multilayer closure. The conjunctiva can be separated from the musculocutaneous flap, and a cartilage graft can be placed for added support as this flap typically has little or no tarsus within it.2 The flap is divided at approximately 6 weeks with 2 mm excess vertical height. This allows for the removal of 1 to 2 mm of musculocutaneous tissue and anterior rotation of a conjunctival flap, which in turn provides a lid margin with a mucous membrane lining instead of keratinized epithelium. The lower eyelid often requires revision. The disadvantages of this repair include (1) a two-stage reconstruction with obstructed vision between stages, (2) disturbance to the lower eyelid that may require future revision and/or lid-tightening procedures, and (3) lack of lashes in the reconstructed segment.

The Tenzel semicircular flap is a regional flap that provides tissue for both the anterior and posterior lamellae.8 A superiorly based semicircular flap of up to 6 cm in diameter is designed and advanced medially. A canthotomy is required; and once advanced, the flap must be secured to the lateral orbital wall to provide support and help recreate the natural convexity of the upper eyelid. The conjunctiva is also undermined and advanced to provide the lining of the flap. This flap is ideally suited for those defects that encompass 40% to 60% of the upper eyelid.2

For large defects (those greater than 75%), the Mustarde lower lid switch flap is an option.9 A large full-thickness portion of the lower eyelid is rotated based on the marginal vessels to fill the upper eyelid defect. This flap is typically delayed up to 6 weeks before pedicle division and inset. This flap provides a composite reconstruction of the upper eyelid and, therefore, the possibility for adequate protection of the globe. The disadvantage is that it sacrifices a significant portion of the lower eyelid that must then be reconstructed with cheek advancement and posterior lamella grafts.

Other options for large upper eyelid defects that involve other surrounding zones include a forehead flap, a Fricke flap, or a glabellar flap (see section “Zone 3: Medial Canthal Reconstruction”). The Fricke flap borrows lower forehead tissue as a laterally based unipedicled flap, which can be transposed to reconstruct either an upper or lower eyelid defect.

Zone 2: Lower Eyelid Reconstruction

Lower eyelid defects are more common than defects in other zones because of the higher incidence of lower eyelid skin cancer (Chapter 14). The lower eyelid is anatomically analogous to the upper eyelid, that is, where the capsulopalpebral fascia is homologous to the levator aponeurosis and the inferior tarsal muscle is homologous to Mueller’s muscle. The main difference is that the lower eyelid is shorter and the tarsal plate is 4 mm in vertical height compared with 10 mm in the upper eyelid. Although lower eyelid position is extremely important in protecting the globe and preventing dryness, it plays a relatively passive role when compared with the upper lid.

Reconstruction of the lower eyelid can be approached algorithmically. Similar to the upper eyelid, lower eyelid defects are treated based on size and on which layer is missing. For superficial defects involving up to 20% of lower lid length, primary closure is usually possible in older patients; younger eyelids have less laxity. As the wound approaches 50%, closure with local tissue advancement is required and, in many cases, a lateral canthotomy is required. A tension-free repair is necessary or lid malposition will result. There are aesthetic benefits to using the normal lid margin when local tissue advancement is utilized in comparison to reconstructive options that reconstruct the lid margin with other tissues.

For superficial defects greater than 50% of lid length with a healthy wound bed, a full-thickness skin graft is a good option. Alternative options are local myocutaneous flaps, including the unipedicled Fricke flap and the bipedicled Tripier flap. The Tripier flap is a bipedicled flap from the upper eyelid transposed to reconstruct lower eyelid defects. This flap includes preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle. The Fricke flap is similar but is a unipedicled flap and is adequate for defects that extend to the mid-lower eyelid or just beyond. The bipedicled option is better utilized in larger defects. Both flaps incorporate more soft tissue than a full-thickness skin graft and, thus, provide for a thicker reconstruction that may require revisional debulking.

Small full-thickness lower lid defects are closed primarily. Care is taken to align and repair the tarsal plate. As in partial-thickness defects, a lateral inferior cantholysis may be required to prevent tension. To avoid dog-ear formation at the inferior aspect of the closure, the incision should be slanted laterally or a Burow’s triangle can be removed.

Once defects are greater than a few millimeters, they are best divided into those that involve <50% of the lower eyelid, 50% to 75% of the lower eyelid, and >75% of the lower eyelid. Full-thickness defects that are 50% or less of the lower eyelid can be approached with the inferiorly based Tenzel semicircular flap.8 The semicircular incision extends superiorly and laterally with a diameter of 3 to 6 cm depending on the defect size and tissue laxity. Dissection is in a submuscular plane, and the inferior ramus of the lateral canthal tendon is divided to allow medial rotational advancement. In larger defects, there may be a paucity of support laterally since the tarsus is advanced medially. In these cases, the flap can be supplemented with a laterally based periosteal flap, conchal cartilage, or septal cartilage. The flap can also be supported with sutures to the lateral orbital periosteum.

For defects larger than 50%, the anterior and posterior lamellae are typically reconstructed separately. For lateral full-thickness defects involving 50 to 75% of the lower eyelid margin, the posterior lamella can be addressed with the Hewes procedure.10 A laterally based upper eyelid tarsoconjunctival flap is pedicled on the superior tarsal artery and transposed to the lower eyelid. The anterior lamella can then be reconstructed with a skin graft or a second upper eyelid flap such as the Tripier flap. When defects of this size are centrally located, the Hewes procedure may not provide enough length for transposition; and a tarsoconjunctival graft is an alternative option. When the posterior lamella is reconstructed with a nonvascularized graft, the anterior lamella must incorporate well-vascularized tissue. Options include a myocutaneous flap from the upper eyelid or vertical myocutaneous flap from the lower eyelid and cheek.2 The vertically based myocutaneous flap is developed just as a skin muscle flap is elevated in a lower blepharoplasty. On vertical advancement, triangles of redundant tissue are removed.

An alternative method for reconstruction of the posterior lamella is the Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap procedure6 from the upper lid which is best for defects greater than 50%, including total lower eyelid reconstructions. The flap is developed starting 4 mm above the upper eyelid margin to avoid compromising upper eyelid integrity and consists of a segment of tarsus and conjunctiva. The width is designed to match the missing posterior lamella segment of the lower eyelid and advanced into the lower eyelid defect. The advanced tarsal segment is secured to the remaining lower eyelid tarsal borders, canthal tendons, or periosteum depending on what remains. This vascularized flap is then covered with a full-thickness skin graft or a myocutaneous flap obscuring vision for several weeks. Separation of the Hughes flap can be performed at 3 to 6 weeks. At this stage, care is taken to allow both Muller’s muscle and the levator to retract to their native positions to preserve upper eyelid function. In addition, in the lower eyelid the conjunctiva is rolled over the recreated lid margin to prevent irritation from corneal contact with keratinized skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree