Reconstruction of the Breast Conservation Patient

Sumner A. Slavin

As a result of numerous trials, breast-conserving surgery combined with radiation therapy has become accepted as the therapeutic equal of modified mastectomy. Specific comparisons relating to long-term survival, locoregional recurrence, and distant metastases confirm the efficacy of breast conservation (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). The technique has gained enormous popularity because it appears to eradicate breast cancer without risking increased recurrence at the primary site, yet preserving a maximal volume of breast tissue. Early concerns of an increased risk of second malignancy, contralateral breast cancer, or radiation-induced sarcoma have not been realized. Although considered a safe technique because it limits the extent of the surgery necessary for tumor ablation, breast conservation can be associated with arm edema when axillary dissection is performed as part of the treatment (9,10). Furthermore, the safety of breast conservation has not conclusively been demonstrated in patients with multicentric disease or those having an extensive intraductal component because of the significantly higher risk of recurrence in patients with these specific findings (11). Most important, however, it has emerged as the preferred treatment for patients with early-stage breast cancer (stages I and II) because of its positive impact on quality of life issues (12).

Technique of Breast Conservation

Although the surgical guidelines for lumpectomy and quadrantectomy have been described by various authors, the specific indications have been altered to meet the needs and demands of the individual patient. In general, tumor size should not exceed 4 cm, and the completed excision must include a 1-cm border of normal parenchyma surrounding the lesion. Skin incisions should be located directly over the lesion, and skin and subcutaneous tissues are usually preserved, except when tumor involves these structures. Closure of the wound involves subcuticular technique and avoidance of drains. In those situations where a wider excision is elected, such as quadrantectomy or partial mastectomy (the umbrella term for a variety of excisions that remove segments of breast tissue), skin may be included in the procedure along with resection of subcutaneous fat and underlying fascia. The resulting deformity after lumpectomy or quadrantectomy depends on a number of factors, including initial breast size, tumor size, dosage of radiation, location of tumor, surgical technique, and adjuvant chemotherapy (13,14,15). Of these, the volume of breast parenchyma removed as a proportion of the total breast size may be the most critical. Patients with large or pendulous breasts can tolerate resections larger than 4 cm, whereas patients with small breasts might develop an unacceptable cosmetic result with a similar size or even smaller excision. Poor surgical technique adversely impacts the outcome because it can predispose the wound to diminished tissue vascularity and severe contracture as scar tissue fills into areas of dead space. Similarly, radiation therapy renders the soft tissues of the breast ischemic, further contributing to fibrosis and scar tissue formation. As radiation therapy techniques using higher-energy photon beams have improved, it has become feasible to remove tumors without consideration of breast size.

Because breast conservation is predicated on achieving tumorfree margins around the original lesion, it is not surprising that rates of recurrence correlate directly with positive surgical margins and the presence of in situ disease with necrosis (16,17,18). It is generally recommended that re-excision be performed if pathologically negative margins cannot be achieved, thus adding to the limits of the original excision and the creation of more dead space (19,20). If more than one re-excision is needed, both the surgeon and the patient find themselves in the dilemma of an increasing defect size that encompasses a higher percentage of breast volume. There is no absolute rule regarding a numerical limit for re-excisions. In most cases, the limiting factors will be breast size, defect dimensions, multicentric disease, and patient choice.

Cosmetic Results After Breast Conservation

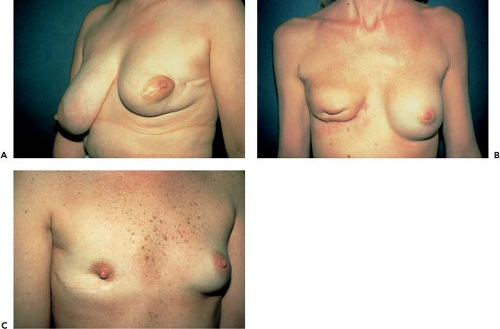

Although many studies have shown that a majority of patients are satisfied with the cosmetic results of conservative surgery and radiation therapy (21,22), there is considerable subjectivity complicating the various rating systems used (Fig. 15.1). Most studies use an observer-based scale that compares the normal with the treated side (23). The observer may vary from patient to radiotherapist, surgeon, or plastic surgeon, with patients generally assigning a higher score and plastic surgeons more critical in their assessment of the aesthetic result (13). In general, attempts are made to quantitate the various aspects of the result that determine the final cosmetic appearance, including degree of telangiectasia formation, breast retraction, and contour disruption. Ultimately, the patient’s perception of the final result supersedes the opinions of all other observers (24,25).

The time course of healing after conservative therapy determines to a great degree the final cosmetic result. For many patients, early healing after surgery and radiation therapy is characterized by edema, occurring most commonly during the first year posttreatment. Edema can mask some of the loss of breast volume, especially in the patient with a larger tumor and smaller breast size. Tumor location within the breast also correlates with worsened cosmesis, as does, of course, tumor size

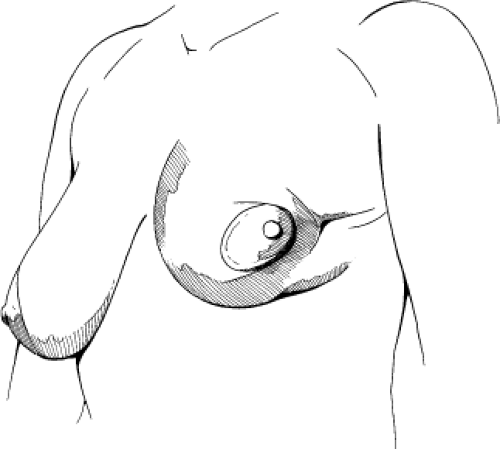

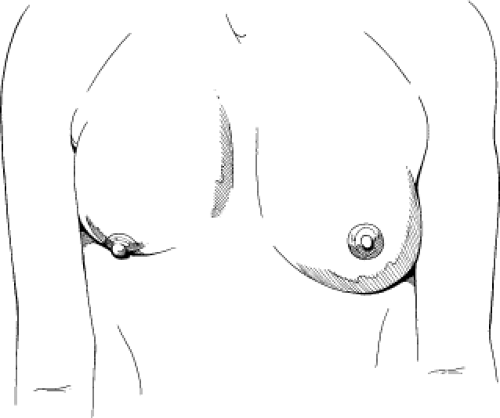

(24). Lesions located within the lower pole of the breast may become more evident as the breast tissues displace or retract upward. Similarly, lesions along the superior pole of the breast or the superomedial aspect are notoriously difficult to camouflage by the usual methods of repair, perhaps because of insufficient tissues available for reconstruction in those areas. They are also in a socially conspicuous location that compounds the magnitude of the deformity. Centrally located lesions are generally favorable in terms of cosmetic outcome, except when a subareolar tumor requires sacrifice of all or a portion of the nipple-areola complex. Loss of any portion of the nipple-areola complex accentuates deformity of the breast surface (Figs. 15.2 and 15.3). Although tumor size is a critically important factor affecting cosmetic outcomes after breast conservation, the amount of surrounding parenchyma and the depth of the original lesion may be as significant as the particular quadrant involved.

(24). Lesions located within the lower pole of the breast may become more evident as the breast tissues displace or retract upward. Similarly, lesions along the superior pole of the breast or the superomedial aspect are notoriously difficult to camouflage by the usual methods of repair, perhaps because of insufficient tissues available for reconstruction in those areas. They are also in a socially conspicuous location that compounds the magnitude of the deformity. Centrally located lesions are generally favorable in terms of cosmetic outcome, except when a subareolar tumor requires sacrifice of all or a portion of the nipple-areola complex. Loss of any portion of the nipple-areola complex accentuates deformity of the breast surface (Figs. 15.2 and 15.3). Although tumor size is a critically important factor affecting cosmetic outcomes after breast conservation, the amount of surrounding parenchyma and the depth of the original lesion may be as significant as the particular quadrant involved.

Figure 15.2. Nipple-areola deformity after breast conservation. The nipple is dislocated inferiorly by scar contracture, radiation-induced fibrosis, and an absence of parenchyma. |

After radiation therapy treatment, the breast can undergo a variety of changes, including edema, retraction, fibrosis, calcification, hyperpigmentation, depigmentation, telangiectasia formation, and atrophy. Although edema may be the hallmark of the earliest phase of healing, it is replaced by fibrosis and retraction, usually occurring after the first 1 to 2 years. For most patients, radiation-induced changes stabilize at approximately 36 months after treatment. Unfortunately, however, the overall cosmetic outcome tends to worsen with the passage of time.

Chemotherapy’s influence on cosmetic outcomes has been evaluated in a number of studies that indicate diminished cosmesis when it is administered sequentially or concurrently with radiation therapy (26,27,28). Although controversial, it appears that

increased breast retraction, more than any other cause, accounts for the decreased incidence of good to excellent results.

increased breast retraction, more than any other cause, accounts for the decreased incidence of good to excellent results.

Figure 15.3. Lower pole deformity of the breast. In addition to skin loss, a large soft-tissue deficiency exists in these situations. |

Similarly, tamoxifen also may exert a negative influence on the final cosmetic appearance of the breast because an increased incidence of hyperpigmentation, telangiectasia, and fibrosis has been associated with it. When combined with radiation therapy, tamoxifen does not adversely impact the cosmetic result. However, it can induce radiation recall in conjunction with breast erythema and persistent edema (29).

Timing of Reconstruction of the Partial Mastectomy Defect

Given the alternating changes of edema and retraction developing after breast conservation, reconstruction should not be commenced until a stable breast appearance has been attained. Although this can occur anytime from 1 to 3 years after treatment, the plastic surgeon should confer with the radiotherapist regarding evolutionary changes in the tissues after radiation and should be aware of any tumor boosts or supplementary therapies. Worsening cosmesis, as may occur when the treated breast retracts superiorly while the contralateral one becomes more ptotic, can be an indication for intervention. However, an optimal reconstructive outcome must consider ongoing changes and anticipate future ones.

In addition, any plastic surgeon planning a reconstructive procedure for the patient with an established lumpectomy or partial mastectomy deformity should consider the patient’s overall risk of recurrence and the measures required for proper oncologic surveillance in this group. Patients must be followed by physical examination and mammographic evaluation. It is not unusual that the plastic surgeon who has reconstructed a breast conservation deformity may be the first to detect recurrent breast cancer.

Approximately 35% of recurrences are detected by mammography and 40% by physical examination. Patients who are younger or have an extensive intraductal component, large tumor size, or positive nodal status have an increased incidence of recurrence. The recurrence presents more commonly as a subtle skin thickening rather than as a palpable lesion. Unfortunately, fibrotic changes within the breast after surgery or radiation therapy can mimic the physical characteristics of a recurrence. A biopsy should always be performed if any new physical finding is encountered, particularly in the higher-risk patient.

Classification of Breast Deformities After Conservative Cancer Surgery and Radiation Therapy

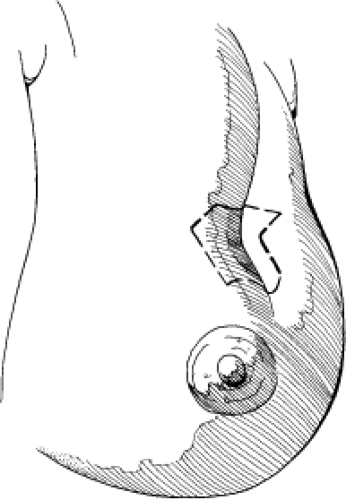

Deformities of the breast after conservation occur in a spectrum of severity, depending on the extent of tissue resected, location, types of tissues involved, and local effects of radiation at the wound site (14,30). As a generalization, all such deformities involve injury to the cutaneous and parenchymal components of the breast. Involvement of the nipple-areola complex, usually in the form of tethering or displacement, creates an unusually severe problem that is most difficult to correct.

Previous investigators have classified the different types of problems as types I to IV, depending on the status of the nipple-areola complex, localized tissue deficiencies, degree of breast retraction, and distortion due to irradiation (31). This complex but thorough method of classification correlates the deformity type with a variety of surgical solutions, including Z-plasties, scar tissue revision, and use of local flaps. For mild deformities, local flap transposition has been recommended as the treatment of choice, reserving myocutaneous flaps for the most extensive defects. In type II deformities in which there has been shrinkage and retraction of breast parenchyma, the authors consider subpectoral augmentation with implants as a possible approach.

Table 15.1 Classification of Breast Deformity After Conservative Surgery and Radiation Therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A simpler preoperative classification of the partial mastectomy deformity has been proposed that considers only three possible factors: skin, parenchyma, and the nipple-areola complex (14) (Table 15.1 and Fig. 15.4). Despite the myriad deformities that are possible on the basis of combinations of injuries to those three tissues, all require flap transposition for correction. Although the treatment approach has been simplified, a careful analysis of the components of the deformity is necessary for a successful aesthetic result. Certainly, the extensive defect created by a quadrantectomy will require placement of a flap.

In such instances, there is a cutaneous and parenchymal deficiency that requires considerable soft-tissue replacement, extending from skin surface to pectoralis major fascia (32).

In such instances, there is a cutaneous and parenchymal deficiency that requires considerable soft-tissue replacement, extending from skin surface to pectoralis major fascia (32).

Patient Selection and Evaluation

During a 12-year period, 51 patients have been reconstructed for radiated partial mastectomy deformities. Initially, patients were mostly self-referred because of dissatisfaction with their aesthetic result. Few were referred by surgeons or radiation oncologists, perhaps because their cancer treatment was considered to be complete. As breast conservation practitioners have aspired to eliminate or minimize deformity, the rationale for needing any type of breast reconstruction has become less evident, and indeed, most patients are satisfied with their cosmetic results after conservation therapy. For the small percentage of patients who are not satisfied, estimated at 5% to 10%, lumpectomy with partial breast reconstruction offers an additional enhancement of body image. Some patients delay reconstructive plans for fear that reconstruction will conceal or otherwise impede the detection of a recurrence; although they prefer reconstruction, they are afraid its consequences. At the outset, explanations of the safety of partial mastectomy reconstruction should be provided. Each patient should be aware of the need for continuing physical examinations and mammographic surveillance.

Evaluation of the breast deformity involves a critical analysis of what tissues are absent or injured. Although skin is not routinely removed as part of breast-conserving surgery, it may have been altered by wound healing and radiation therapy. Invariably, there is a relative skin loss that requires some degree of correction. Evaluation of the cutaneous component is the single most deceptive aspect of the preoperative evaluation (Figs. 15.5 to 15.7). Notation of the quality of the skin, including textural and surface abnormalities, is an important part of a preoperative analysis, as is observation of abnormalities in pigmentation and vascularity. As the existing skin incision is reopened, the wound edges retract in response to the release of tethering unleashed by radiation fibrosis and contraction.

By definition, every patient has a parenchymal deficit, but precisely what volume is absent is difficult to determine. Notation should be made of the quality of skin, tightness, surface contour irregularities, and the presence of significant depression along the breast surface. Retraction of skin into breast parenchyma indicates a possible tethering to the deeper limits of the breast or even to fascia. Severe contour deformity always indicates marked volume loss in all directions.

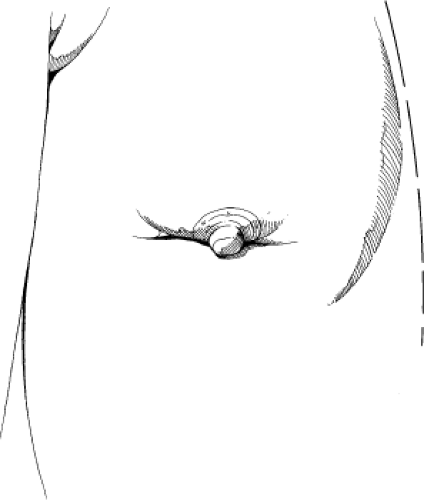

When abnormalities of the nipple-areola complex are present, a larger cutaneous component is needed because buried dermis provides a more reliable tissue support structure than does subcutaneous fat or muscle. Usually, the entire nipple-areola complex is present, but certain elements may have been markedly altered by the previous treatment. The nipple itself may become depressed by lack of supporting structures, eliminating its projection above the skin surface. In more extreme cases, the areolar skin completely engulfs and conceals the presence of the nipple. Portions of the areolar skin can retract and fold, producing a false appearance of missing skin. Sometimes the full extent of the loss of any anatomic component may not be realized until reconstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree