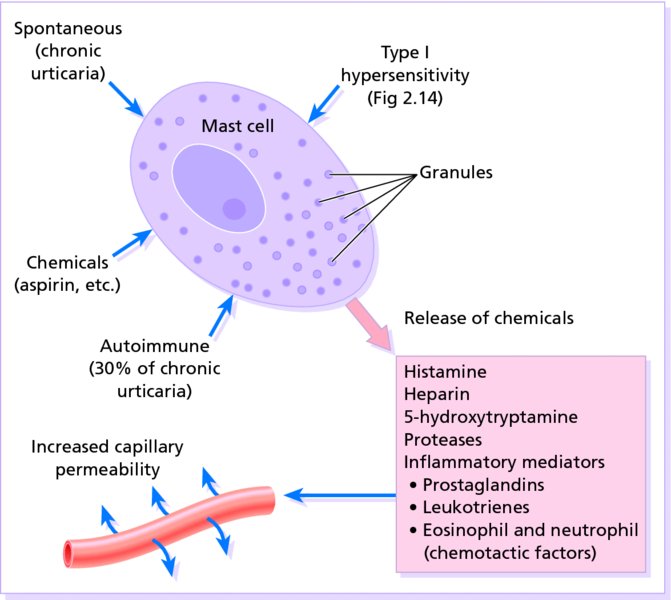

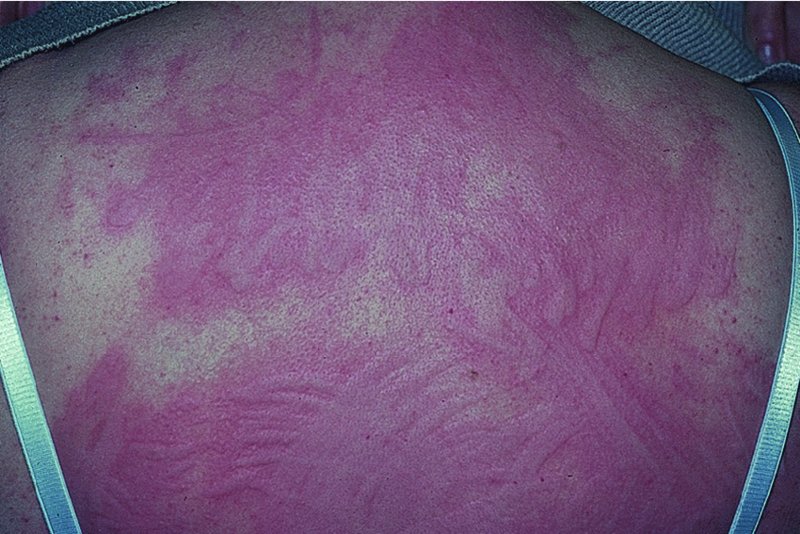

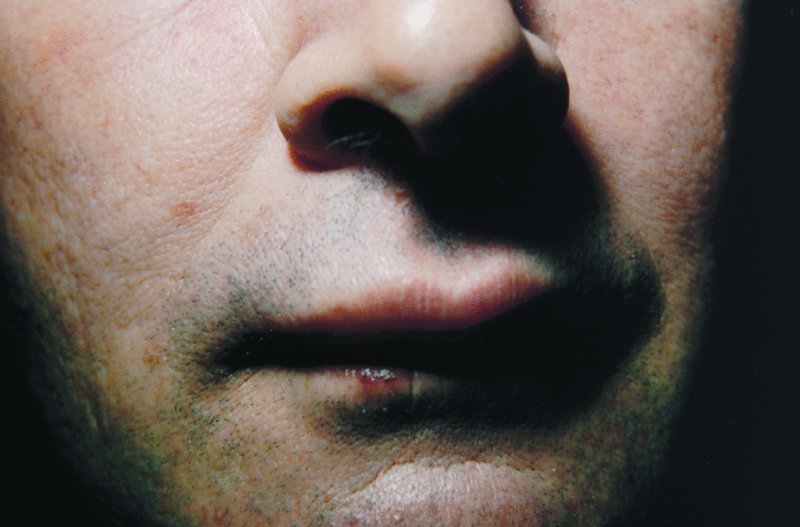

8 Blood vessels can be affected by a variety of insults, both exogenous and endogenous. When this occurs, the epidermis remains unaffected, but the skin becomes red or pink and often oedematous. This is a reactive erythema. If the blood vessels are damaged more severely – as in vasculitis – purpura or larger areas of haemorrhage mask the erythematous colour. Urticaria is a common reaction pattern in which pink, itchy or ‘burning’ swellings (wheals) can occur anywhere on the body. Individual wheals do not last longer than 24 hours, but new ones may continue to appear for days, months or even years. Traditionally, urticaria is divided into acute and chronic forms, based on the duration of the disease rather than of individual wheals. Urticaria that persists for more than 6 weeks is classified as chronic. More recently, episodic (acute intermittent or recurrent activity) has been added to the classification. Most patients with chronic urticaria, other than those with an obvious physical cause, have what is often known as ordinary urticaria. Chronic ordinary urticaria (COU) can be further subdivided depending on the presence (30%) or absence (70%) of histamine-releasing autoantibodies; giving rise to the somewhat cumbersome terms, autoimmune chronic ordinary urticaria and idiopathic chronic ordinary urticaria, respectively. The signs and symptoms of urticaria are caused by mast cell degranulation, with release of multiple vasoactive substances, including histamine (Figure 8.1). The mechanisms underlying this may be different but the end result, increased capillary permeability leading to transient leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissue and development of a wheal, is the same (Figure 8.1). For example, in autoimmune COU circulating antibodies are directed against the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor (FcIgE) or receptor bound IgE on mast cells whereas the reaction in others in this group may be caused by immediate IgE-mediated hypersensitivity (see Figure 2.14), direct degranulation by a chemical or trauma, or complement activation. Figure 8.1 Ways in which a mast cell can be degranulated and the ensuing reaction. The various types of urticaria are listed in Table 8.1. They can often be identified by a careful history; laboratory tests are less useful. The duration of the wheals is an important pointer. Contact and physical urticarias, with the exception of delayed pressure urticaria, start shortly after the stimulus and go within an hour. Individual wheals of other forms resolve within 24 hours. If they persist for longer, then urticarial vasculitis should be considered (see Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis). Table 8.1 The main types of urticaria. Patients develop wheals in areas exposed to cold (e.g. on the face when cycling or freezing in a cold wind). A useful test in the clinic is to reproduce the reaction by holding an ice cube, in a thin plastic bag to avoid wetting, against forearm skin. A few cases are associated with the presence of cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins or cryofibrinogens. Wheals occur within minutes of sun exposure. Some patients with solar urticaria have erythropoietic protoporphyria (p. 317); most have an IgE-mediated urticarial reaction to sunlight. In this condition wheals arise in areas after contact with hot objects or solutions. Anxiety, heat, sexual excitement or strenuous exercise elicits this characteristic response. The vessels overreact to acetylcholine liberated from sympathetic nerves in the skin. Transient 2–5 mm follicular macules or papules (Figure 8.2) resemble a blush or viral exanthem. Some patients get blotchy patches on their necks. Figure 8.2 Typical small transient wheals of cholinergic urticaria – in this case triggered by exercise. Figure 8.3 Dermographism: a frenzy of scratching by an already dermographic individual led to this dramatic appearance. This is the most common type of physical urticaria, the skin mast cells releasing extra histamine after rubbing or scratching. The linear wheals are therefore an exaggerated triple response of Lewis. They can readily be reproduced by rubbing the skin of the back lightly at different pressures, or by scratching the back with a fingernail or blunt object. Sustained pressure causes oedema of the underlying skin and subcutaneous tissue 3–6 hours later. The swelling may last up to 48 hours and kinins or prostaglandins rather than histamine probably mediate it. It occurs particularly on the feet after walking, on the hands after clapping and on the buttocks after sitting. It can be disabling for manual labourers. This common form of urticaria is caused by hypersensitivity, often an IgE-mediated (type I) immediate hypersensitivity reaction (see Chapter 2). Allergens may be encountered in 10 different ways (the 10 I’s listed in Table 8.2). Table 8.2 The 10 I’s of antigen encounter in hypersensitive urticaria. About 30% of patients with COU have an autoimmune disease with IgG antibodies to IgE or to FcIgE receptors on mast cells. Here the autoantibody acts as antigen to trigger mast cell degranulation. This occurs when drugs cause mast cells to release histamine in a non-allergic manner (e.g. opiates such as codeine and morphine, and radiocontrast media). Urticaria provoked by aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and certain food substances may also involve leukotriene release. This may be IgE-mediated or caused by a pharmacological effect. The allergen is delivered to the mast cell from the skin surface rather than from the blood. Wheals occur most often around the mouth. Foods and food additives are the most common culprits but drugs, animal saliva, caterpillars, insect repellents and plants may cause the reaction. Latex allergy has become a significant public health concern although the incidence now appears to be falling. Possible skin reactions to the natural rubber latex of the Hevea brasiliensis tree include irritant dermatitis, contact allergic dermatitis (see Chapter 7) and type I (immediate hypersensitivity) allergy (see Chapter 2). Reactions associated with the latter include hypersensitivity urticaria (both by contact and by inhalation), hay fever, asthma, anaphylaxis and, rarely, death. Medical latex gloves became universally popular after precautions were introduced to protect against HIV and hepatitis B infections. The demand for the gloves increased and this led to alterations in their manufacture and to a flood of high allergen gloves on the market. Cornstarch powder in these gloves bound to the latex proteins so that the allergen became airborne when the gloves were put on. Individuals at increased risk of latex allergy include health care workers, those undergoing multiple surgical procedures (e.g. patients with spina bifida) and workers in mechanical, catering and electronic trades. Around 1–6% of the general population is believed to be sensitized to latex. Latex reactions should be treated on their own merits (see Urticaria treatment, p. 104 and Figure 25.5 for anaphylaxis and Chapter 7 for dermatitis). Prevention of latex allergy is equally important. Non-latex (e.g. vinyl) gloves should be worn by those not handling infectious material (e.g. caterers) and, if latex gloves are chosen for those handling infectious material, then powder-free low allergen ones should be used. Most types of urticaria share the sudden appearance of pink itchy wheals, which can come up anywhere on the skin surface (Figures 8.4 and 8.5). Each lasts for less than a day, and most disappear within a few hours. Lesions may enlarge rapidly and some resolve centrally to take up an annular shape. In an acute anaphylactic reaction, wheals may cover most of the skin surface. In contrast, in chronic urticaria only a few wheals may develop each day. Figure 8.4 A classic wheal. Figure 8.5 Severe and acute urticaria caused by penicillin allergy. Angioedema is a variant of urticaria that primarily affects the subcutaneous tissues, so that the swelling is less demarcated and less red than an urticarial wheal. Angioedema most commonly occurs at junctions between skin and mucous membranes (e.g. peri-orbital, peri-oral and genital; Figure 8.6). It may be associated with swelling of the tongue and laryngeal mucosa. It sometimes accompanies chronic urticaria and its causes may be the same. Angioedema without wheals may be the presenting feature of hereditary angioedema (see Hereditary angioedema) or more commonly as a result of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor consumption (thought to result from the inhibition of kinin degradation). Figure 8.6 Angioedema of the upper lip. The course of an urticarial reaction depends on its cause. If the urticaria is allergic, it will continue until the allergen is removed, tolerated or metabolized. Most such patients clear up within a day or two, even if the allergen is not identified. Urticaria may recur if the allergen is met again. At the other end of the scale, only half of patients attending hospital clinics with chronic urticaria and angioedema will be clear 5 years later. Those with urticarial lesions alone do better, half being clear after 6 months. Urticaria is normally uncomplicated, although its itch may be enough to interfere with sleep or daily activities and to lead to depression. In acute anaphylactic reactions, oedema of the larynx may lead to asphyxiation, and oedema of the tracheo-bronchial tree to asthma. There are two aspects to the differential diagnosis of urticaria. The first is to tell urticaria from other eruptions that are not urticaria at all. The second is to define the type of urticaria, according to Table 8.1. Insect bites or stings (Figure 8.7) and infestations commonly elicit urticarial responses, but these may have a central punctum and individual lesions may last longer than 24 hours. Erythema multiforme can mimic an annular urticaria. A form of vasculitis (urticarial vasculitis; p. 109) may resemble urticaria, but individual lesions last for longer than 24 hours, are typically associated with a more burning pain, blanch incompletely and leave bruising in their wake. Some bullous diseases, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis, begin as urticarial papules or plaques but, later, bullae make the diagnosis obvious. In these patients, individual lesions last longer than 24 hours, providing an additional tip-off for further investigation (see Chapter 9). On the face, erysipelas can be distinguished from angioedema by its sharp margin, redder colour and accompanying pyrexia. Hereditary angioedema (see Hereditary angioedema) must be distinguished from the angioedema accompanying urticaria as their treatments are completely different. Figure 8.7 A massive urticarial reaction to a wasp sting. The investigations will depend upon the presentation and type of urticaria. Many of the physical urticarias can be reproduced by appropriate physical tests. It is important to remember that antihistamines should be stopped for at least 3 days before these are undertaken. Almost invariably, more is learned from the history than from the laboratory. The history should include details of the events surrounding the onset of the eruption. A review of systems may uncover evidence of an underlying disease. Careful attention should be paid to drugs, remembering that self-prescribed ones can also cause urticaria. Over-the-counter medications (such as aspirin and herbal remedies) and medications given by other routes (Table 8.2) can produce wheals. If a patient has ordinary urticaria and its cause is not obvious, investigations are often deferred until it has persisted for a few weeks or months, and are based on the history. If no clues are found in the history, investigations can be confined to a complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). An eosinophilia should lead to consideration of bullous or parasitic disease, and a raised ESR might suggest urticarial vasculitis, or a systemic cause. If the urticaria continues for 2–3 months, the patient may be referred to a dermatologist for further evaluation. In general, the focus of such investigations will be on internal disorders associated with urticaria (Table 8.3) and on external allergens (Table 8.4

Reactive Erythemas and Vasculitis

Urticaria (hives, ‘nettle-rash’)

Cause

Classification

Ordinary urticaria

Acute (up to 6 weeks of continuous activity)

Chronic (more than 6 weeks of continuous activity)

Episodic (acute intermittent or recurrent activity)

Physical

Cold

Solar

Heat

Cholinergic

Dermographism (immediate pressure urticaria)

Delayed pressure

Hypersensitivity

Autoimmune

Pharmacological

Contact

Physical urticarias

Cold urticaria

Solar urticaria

Heat urticaria

Cholinergic urticaria

Dermographism (Figure 8.3)

Delayed pressure urticaria

Other types of urticaria

Hypersensitivity urticaria

Ingestion

Inhalation

Instillation

Injection

Insertion

Insect bites

Infestations

Infection

Infusion

Inunction (contact)

Autoimmune urticaria

Pharmacological urticaria

Contact urticaria

Latex allergy

Presentation

Course

Complications

Differential diagnosis

Investigations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree