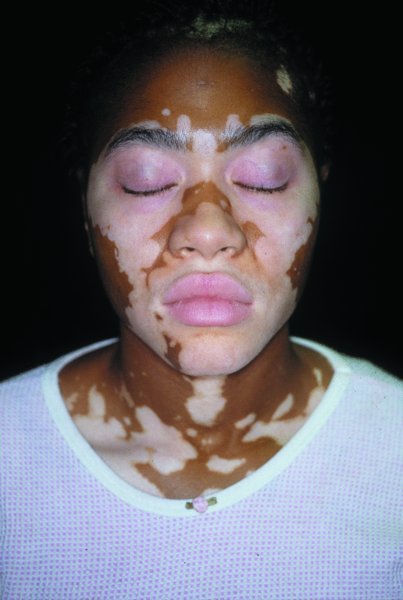

14 Historical views on racial classification have been largely superseded by the understanding that biological variation does not fall into well-demarcated categories, but is a continuum. Greater genetic variance is found between individuals within traditionally described ‘races’ than between races. The most obvious difference in the appearance of humans around the world is skin colour. Evolution favoured a dark skin in those exposed to high amounts of sunlight, thereby protecting the skin from damaging ultraviolet rays. It favoured a lighter skin in those living further from the equator to promote the production of vitamin D. These two competing evolutionary pressures favour a range of skin colours dependent on different UV exposure. This has been confirmed by studying latitude and skin colour as measured by reflectance spectrophotometry (Table 14.1). Dark skin differs from light skin not only in its colour, but also in its structure and function. Table 14.1 Skin colour (measured by reflectance at 685nm) and latitude. Lower numbers represent darker skin. Adapted from Jablonski and Chaplin, Journal of Human Evolution (2000). No colour defines normal skin and the same skin diseases occur in all parts of the world. Because of both genetic and environmental differences, skin diseases in those with pigmented skin often differ from those with non-pigmented skin in their incidence, prevalence, appearance and behaviour. They also differ in the types of cosmetic impairment they produce. For example, an acne papule in a white person can cause a transient mild tan or pink colour after the inflammation subsides, but the same papule may produce a long-lasting black macule in an African with darker skin. For the most part, melanin determines the colour of the skin. Other determinants that modify colour are capillary blood flow, carotene, lycopene, dermal collagen and the amounts of absorbed or reflected colours of light. As discussed in detail in Chapter 2, each melanocyte supplies melanin to about 30 nearby keratinocytes and it is the type, amount and distribution of melanin in keratinocytes that determines the colour of the skin. Tyrosinase in melanosomes converts tyrosine to dopa and then dopa to dopaquinone. This generates eumelanin, which is a dark brown–black colour. Eumelanin is plentiful in the dark skin of Africans and East Indians. Pheomelanin is yellow–red and forms when dopaquinone combines with cysteine or glutathione (p. 268). It is more plentiful in freckles in the light skin of Celtic populations in northern Europe. As people of the same race may have a darker or lighter skin, dermatologists use skin typing numbers to grade baseline pigmentation. These skin types range from the pale, white, sun burning skin of type I individuals to the dark brown or black, never sun burning skin of type VI individuals. Skin types are assigned by criteria listed in Table 18.1). Despite obvious differences in colour, the skin of the various races is remarkably similar in structure and function. However, the epidermis is often thicker in dark skin, perhaps because it is less photodamaged. The stratum corneum of African skin may be more compact and contain higher concentrations of lipids. Functional differences in sweating may be ascribed to acclimatization and climate. Fibroblasts are larger and more numerous in black than in white skin and the collagen bundles are finer and stacked more closely together. They may also be more active. This, combined with the decreased collagenase activity of black skin, predisposes it to form keloids. African hair is more likely to be spiral in type, rather than straight, wavy or helical. African hair shafts tend to be more elliptical and hair follicles more curved. Asian hair has the largest cross-sectional area, while hair of western Europeans has the smallest. Native Americans and Mayan Indians have hair with large round cross-sections. Darker skin seems more resistant to irritation, but this may be because erythema is difficult to see in dark skin, so visual measures of irritation falsely under-estimate the degree of inflammation. Chemicals penetrate black skin at about the same rate as they penetrate white skin so skin irritants produce comparable irritation if this is measured with surrogate markers such as the rate of transepidermal water loss across irritated skin. Common inflammatory conditions may present differently in darker skinned individuals. Erythema is difficult to appreciate in black skin; the overlying pigmentation masks the erythema to give a purplish hue. Pigment alteration may dominate the picture. Inflammation often leaves either dark or light spots; in other words, either it increases melanocyte activity or it increases epidermal turnover so that melanocytes inject less pigment into the surrounding keratinocytes. Although these areas are not scars, patients often refer to them as such and, like scars, they can be unsightly and persistent (Figure 14.1). Figure 14.1 Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Inflammation often stimulates pigment cells to produce excessive melanin, so that previously inflamed areas are marked long afterwards with dark patches. Acne in darker skinned patients causes hyperpigmented macules when papules and pustules resolve. Like the acne itself, these marks are hard to hide and the facial appearance worsens progressively as they accumulate. For this reason, acne in coloured skin calls for more aggressive treatment, but, unfortunately, irritation from acne treatments can also induce hyperpigmentation. Less irritating retinoids such as adapalene (Formulary 1, p. 405) are often preferred and lower concentration in a cream vehicle is more tolerable. Systemic antibiotics should be prescribed earlier in the course of treatment. Azelaic acid preparations (Formulary 1, pp. 399 and 406) lighten the skin while opening comedones and reducing papule counts, so agents containing it are useful for mild cases. Atopic dermatitis may be severe, especially in Asians. Eyelid dermatitis is particularly common and resists the usual treatments. In African patients, eczema has a tendency to surround and involve hair follicles, leading to evenly spaced skin-coloured papules resembling goose flesh. If accompanied by itching, this appearance should suggest eczema in black skin rather than other forms of folliculitis. Lichen nitidus occurs most commonly in black skin. Pinhead-sized uniformly distributed, shiny flat-topped skin-coloured papules occur on the genitals, abdomen or flexor surfaces of the extremities. The lesions do not itch. Skin biopsy establishes the diagnosis. No treatment is necessary; the disease is asymptomatic and goes away after 2–3 months. Lichen planus, classically described as flat-topped papules with a violaceous colour (p. 69), is darker in appearance in black skin. Any inflammation can leave dark spots, but in darker races these are especially prominent and persistent in diseases that damage basal melanocytes and lead to pigmentary incontinence, such as lichen planus, erythema dyschromicum perstans (p. 200) and erythema multiforme (p. 105). Pityriasis alba appears as poorly marginated, light patches on pigmented skin (Figure 19.6). Although it occurs in skin types I and II, it is far more easily seen in darker skin types as the contrast is greater. Sometimes there is fine superficial scaling – hence the term pityriasis. Many patients are children with atopic dermatitis elsewhere. Examination under Wood’s light highlights the pigmentary abnormality. Other provokers of pityriasis alba are bites, sunburn (even among those who are dark skinned), mechanical irritation from scrubbing, or other forms of eczematous dermatitis. The higher the skin type number, the more resistant this disorder is to treatment. Most children with the disease improve at puberty. In vitiligo (p. 298) the spots are much whiter, much more sharply marginated and always without scaling (Figure 14.2). Pityriasis versicolor (p. 245) is also more sharply marginated and is usually scaly (Figure 16.49). Potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination of scraping from these scales should be carried out if there is doubt. Sarcoidosis and leprosy should also be kept in mind. Figure 14.2 Vitiligo. Note the complete loss of pigment and the mirror-like symmetry. If mild eczema is the provoking factor, treatment with a weak corticosteroid such as hydrocortisone 0.5 or 1% or a cream containing a calcineurin inhibitor such as pimecrolimus is often prescribed. However, the pigmentary abnormality will take months to improve. Syndets (synthetic balanced detergents, Formulary 1, p. 398) can be used to wash the face as they are often less irritating than alkaline soaps. Moisturizers can be applied twice daily and after face washing. Tanning does not help; too often it accentuates the contrast. Pityriasis rosea (p. 68) tends to be itchier in blacks and to leave long-standing black macules of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. For that reason, systemic steroids are sometimes given (do not forget to rule out syphilis!). Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma occurs about twice as often in Africans than Caucasians. Persisting pruritic hypopigmented patches may prompt biopsy. Sarcoidosis (p. 313) is up to 18 times more common in blacks than in whites. Its skin manifestations include erythema nodosum, widespread non-scaling papules, flesh coloured or blue–red nodules on the trunk, bulbous purple nodules and plaques on the face or ears (lupus pernio), inflammation in scars (scar sarcoid), soft swellings on the cheeks with overlying telangiectases (angiolupoid sarcoid) and lesions resembling psoriasis or ichthyosis. Sarcoidosis imitates many skin diseases, but biopsy will show its typical granulomas. Patients with darker skin types are more prone to post-inflammatory pigment alteration. This can be a result of their underlying inflammatory disease, but can also occur from iatrogenic effects during treatment. Retinoids have the potential to be irritating, promoting inflammation and hyperpigmentation. Aggressive laser treatments in skin of colour can cause hyperpigmentation. Warts, skin tags and seborrhoeic keratoses treated with cryotherapy can result in hypopigmentation. Treatment for hyperpigmentation is two-fold. First, the primary disease should be suppressed or cured. Secondly, the darker spots can be treated with a bleaching agent such as 4% hydroquinone cream (Formulary 1, p. 399). Proprietary creams containing hydroquinone plus a retinoid, a glucocorticosteroid, or all three are available. Again care has to be taken not to irritate the skin with treatments designed to lighten it. Hydroquinone in concentrations greater than 4% can be compounded but carries a risk of inducing irreversible exogenous pigmentation ochronosis. This darkens the skin and prompts applications of even more hydroquinone. Areas of skin with inflammation or an increased epidermal turnover can leave light spots. These are not completely depigmented and so can be distinguished from vitiligo by their appearance, as well as by their history. Few treatments exist for hypopigmentation. Use of excimer and fractionated laser show modest results at best. Fortunately, hypopigmentation generally resolves with time.

Racial Skin Differences

Skin

Approximate

colour

Latitude

Kenya

32

0° (Equator)

Papua New Guinea (Goroka)

33

6°S

Ethiopian Highlands

34

8°N

South Africa (San)

44

22°S

Libya (Fezzan)

44

24°N

South Africa

51

32°S

Northern England

67

54°N

Greenland (dietary Vitamin D)

56

60°N

Skin types

Racial differences in structure and function

Racially dependent variations in skin conditions

Inflammatory conditions

Acne

Eczema

Lichen nitidus

Lichen planus

Pityriasis alba

Presentation

Course

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Other considerations

Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation

Pigmentary conditions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree