Key Words

ptosis repair, frontalis suspension, congenital ptosis, involutional ptosis, levator advancement, Fasanella-Servat procedure, pseudoptosis, neurogenic ptosis, mechanical ptosis, lagophthalmos

Synopsis

Blepharoptosis or ptosis describes the descent of the upper eyelid below the normal anatomical position, which can result in reduced visual function or, in children, amblyopia. The upper eyelid margin normally lies 0.5 to 2 mm below the superior corneal limbus. Descent of the upper eyelid margin inferiorly can be attributed to myogenic, aponeurotic, neurogenic, or mechanical etiologies that are present at birth (congenital) or acquired. The severity of ptosis is classified as mild (1–2 mm), moderate (3–4 mm), and severe (>4 mm). Treatment of eyelid ptosis necessitates an accurate diagnosis and is dependent on a comprehensive ocular history and physical examination. The history should include the age of onset, visual changes, previous ocular surgery, family history, trauma, episodes of lid swelling, diplopia, presence of any aberrant lid movements, progression of symptoms, associated peripheral muscle weakness, past medical history, and medications. A patient with ptosis may demonstrate compensatory frontalis muscle activation or posturing of the head backward to aid in vision. The degree of ptosis, levator muscle function, tear film production, visual acuity, assessment of visual fields, extraocular muscle function, pupil size and reactivity, and orbicularis oculi integrity should also be determined on physical examination. Levator muscle function is the most important factor in determining the specific surgical intervention for eyelid ptosis. Patients with poor levator function require surgical intervention with a frontalis sling. Patients with moderate to good levator function can be treated with a Fasanella-Servat or conjunctival-Mullerectomy procedure if the eyelid ptosis is mild. As the eyelid ptosis becomes more severe in patients with moderate to good levator function, a levator advancement procedure with or without levator muscle resection is indicated.

Clinical Problem

Blepharoptosis or ptosis is a condition characterized by descent of the upper eyelid margin below its normal anatomical position, which can lead to bothersome asymmetry and visual disturbances. Ptosis is classified as congenital or acquired and has several etiologies that can be grouped into myogenic, aponeurotic, neurogenic, or mechanical disruptions ( Table 3.7.1 ). It is critical to distinguish ptosis from pseudoptosis. Pseudoptosis resembles an inability to elevate the eyelid, and there are several conditions that may mimic a true ptosis. These include Graves’ disease, hypotropia, Duane’s syndrome, post-traumatic enophthalmos, contralateral exophthalmus, dermatochalasis, and chronic squinting.

| Myogenic | Congenital myogenic ptosis Myasthenia gravis Muscular dystrophy

Trauma |

| Aponeurotic | Involutional (due to aging) Trauma |

| Neurogenic | Third cranial nerve palsy Horner’s syndrome Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis Seventh cranial nerve palsy |

| Mechanical | Eyelid mass or tumor Dermatochalasis Scarring |

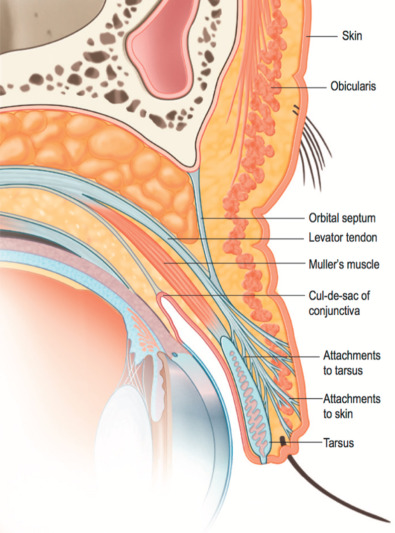

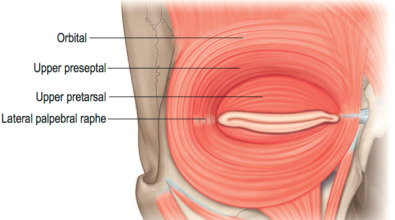

The position of the upper eyelid is maintained by a fine balance of eyelid elevator and depressor muscles that require appropriate innervation, development, and normal anatomical positioning to orchestrate the function of the eye. The eyelid protects and lubricates the cornea by serving as a physical barrier to foreign bodies and restoring tear film with blinking. The upper eyelid is composed of the anterior and posterior lamellae, which are separated by the orbital septum ( Fig. 3.7.1 ). The anterior lamella is most superficial and comprises the eyelid skin and orbicularis oculi muscle. The orbicularis oculi muscle is divided into three components including the orbital, septal, and tarsal portions ( Fig. 3.7.2 ). The tarsal portion is positioned superficial to the tarsal plate and initiates involuntary blinking. The septal component overlies the orbital septum; it is responsible for voluntary blinking and serves as a lacrimal pump for tear drainage. The orbital component is the largest division and functions in forced eyelid closure. The orbicularis oculi receives innervation from the facial nerve and acts as the major upper eyelid depressor. The orbital septum arises from the arcus marginalis and fuses with the levator aponeurosis inferiorly to insert on the tarsal plate. Posterior to the orbital septum, you can identify the pre-aponeurotic fat. This fat can be retracted to expose the levator palpebrae superioris. The levator palpebrae superioris and Muller’s muscle are responsible for upper eyelid elevation. The levator palpebrae superioris is the major elevator of the upper eyelid and is innervated by the oculomotor nerve (CN III). It originates from the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone and inserts onto the anterior surface of the tarsal plate as the levator aponeurosis. The levator aponeurosis also sends fibers to the skin to create the upper eyelid crease approximately 10 mm superior to the eyelid margin. Muller’s muscle originates from the posterior aspect of the levator palpebrae superioris and inserts on the superior border of the tarsal plate via a 1-mm tendon. Muller’s muscle is innervated by the sympathetic nervous system and elevates the upper eyelid approximately 2 mm. The posterior lamella is comprised of the tarsal plate and the conjunctiva. The tarsal plate measures 25 mm in the horizontal direction and 10 mm in the vertical direction.

The normal adult upper eyelid margin is located 0.5 to 2 mm below the superior corneal limbus. Mild ptosis is defined as descent of the eyelid margin 1 to 2 mm below the normal anatomical position. Moderate ptosis occurs when the descent is 3 to 4 mm, and severe ptosis is characterized by descent greater than 4 mm. The treatment of ptosis is contingent on the severity of eyelid descent, the function of the levator palpebrae superioris and Muller’s muscles, the integrity of the innervation to these muscles, and the underlying pathology. Ptosis may be unilateral or bilateral. In patients with unilateral ptosis, there is an increased neural input to the bilateral frontalis and levator muscles as a compensatory response. As a result, this may mask a mild contralateral ptosis that may present after a unilateral ptosis repair once the neural input has normalized. This is known as Hering’s law.

Myogenic causes of ptosis include congenital myogenic ptosis, myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy, trauma, myositis, and infiltrative causes such as lymphoma. Congenital myogenic ptosis presents at birth and results from dysgenesis of the levator muscle. In children, it is imperative to determine whether any disturbances of the visual fields exist because this can hinder normal visual development and lead to amblyopia. Any violation of the visual fields in children is an urgent indication for ptosis repair.

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder that interferes with neural transmission at the neuromuscular junction. These patients typically present with ptosis that worsens throughout the day and is associated with ophthalmoplegia and other skeletal muscle involvement. This condition is treated medically with acetylcholinesterase drugs, systemic steroids, and plasmapheresis.

Muscular dystrophy includes a group of genetic disorders characterized by muscle weakness, progressive bilateral ptosis, and pigmented retinopathy. These conditions include myotonic dystrophy, oculopharyngeal dystrophy, mitochondrial myopathy, and congenital ocular fibrosis syndrome. Conservative ptosis repairs are recommended when indicated due to associated poor lid closure as a result of a weakened orbicularis oculi muscle.

Aponeurotic ptosis results from attenuation of the levator aponeurosis or dehiscence of the aponeurosis from the tarsal plate leading to mild to severe ptosis and elevation of the eyelid crease. These patients usually demonstrate good levator muscle function. This condition usually occurs secondary to involutional changes associated with aging. However, blunt trauma to the eye can initiate levator dehiscence. Levator plication or advancement techniques are used to correct aponeurotic ptosis.

Neurogenic ptosis is caused by cranial nerve III palsies, Horner’s syndrome, Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis, or cranial nerve VII palsies. Palsies of cranial nerve III can result from several conditions including aneurysms, compressive mass within the cavernous sinus, diabetes, and ischemia. Patients usually present with ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, and dilation of the pupil. Treatment involves correction of the underlying pathology, if amenable, and ptosis repair. Horner’s syndrome is caused by interruption of the sympathetic pathway, producing mild ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis. The levator function in Horner’s syndrome is preserved. Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by co-contraction of the levator muscle with stimulation of the trigeminal nerve (e.g., chewing). It is associated with decreased function of the superior rectus muscle. Treatment requires division of the levator muscle and frontalis suspension. In facial nerve palsy, aberrant regeneration of the nerve can cause ptosis via increased or abnormal neural input and activation of orbicularis oculi muscle from lower branches of the facial nerve. This is clinically displayed with ptosis associated with movement of muscles of the lower face and can be addressed by division of the levator muscle and frontalis sling.

Mechanical ptosis is usually due to an excessive eyelid mass or bulk (e.g., severe dermatochalasis) or scarring that inhibits the full elevation or excursion of the eyelid. Treatment of the underlying cause, such as mass excision or scar release, will improve ptosis.

Lastly, blepharophimosis syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that presents with ptosis associated with poor levator function, telecanthus, and epicanthus inversus. Correction of telecanthus and epicanthus inversus should be performed before ptosis repair.

Pre-Operative Management

A detailed and accurate history and physical examination is critical to obtain a correct diagnosis and prescribe an appropriate treatment plan. The history should evaluate the age of onset, visual changes, previous ocular surgery, family history, trauma, episodes of lid swelling, diplopia, presence of any aberrant lid movements, progression of symptoms, associated peripheral muscle weakness, past medical history, and medications.

The physical examination should be performed in a systematic manner starting with observation and progressing to more specific tests as dictated by the examination.

Physical Examination

- •

Frontalis muscle activation, brow position, and head positioning: Patients with upper eyelid ptosis may demonstrate distinctive posturing and compensatory features on physical examination. Frontalis muscle overaction elevates the brow and indirectly the eyelid for improved visual function. Additionally, posturing the head backward is indicative that the ptosis is encroaching on the visual fields. It is important to realize that brow ptosis may exacerbate the perceived eyelid ptosis on physical examination. In males, the eyebrow normally sits at the level of the supraorbital rim. In females, the eyebrow sits approximately 1 cm superior to the supraorbital rim. Positioning the eyebrow to the normal anatomical position with your thumb is indicated to get an accurate assessment of the upper eyelid ptosis if there is concurrent brow ptosis.

- •

Palpebral aperture and upper eyelid margin position: The palpebral aperture is the widest distance between the upper and lower eyelid margins and typically measures 8 to 12 mm. The degree of upper eyelid margin descent determines the severity of ptosis.

- •

Upper eyelid skin crease: The upper eyelid crease is normally located approximately 10 mm superior to the lid margin. In aponeurotic ptosis, the skin crease is usually elevated.

- •

Levator function: Levator muscle function is the most important factor in determining the specific surgical intervention for eyelid ptosis. Excursion of the levator muscle is the measured movement of the eyelid margin from extreme upward to extreme downward gaze ( Fig. 3.7.3 ). To isolate the levator, decrease the input from the frontalis muscle by splinting the eyebrow against the forehead with your thumb. A measurement greater than 10 mm is characterized as good, 5 to 10 mm as moderate, and less than 5 mm as poor.

Fig. 3.7.3

Measurement of levator excursion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree