5 Psoriasis is an immunologically mediated chronic inflammatory skin disease, characterized by well-defined salmon-pink plaques bearing large adherent silvery centrally attached scales. One to three per cent of most populations have psoriasis, which is most prevalent in European and North American white people. It can start at any age but is rare under 10 years, and appears most often between 15 and 40 years. Its course is unpredictable but is usually chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Our understanding of the causes of psoriasis has greatly improved in the last 10 years and this has resulted in the development of a range of valuable new treatments, particularly for more severe disease. Psoriasis is also now seen as an inflammatory disease affecting more than just the skin. Psoriatic arthritis has long been recognized, but studies now show that moderate and severe psoriasis is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. There are two key abnormalities in a psoriatic plaque: hyperproliferation of keratinocytes; and an inflammatory cell infiltrate in which neutrophils, tumour necrosis factor and T lymphocytes predominate. Both of these abnormalities can induce the other, leading to a vicious cycle of keratinocyte proliferation and inflammatory reaction; but it is still not clear which is the primary defect. Perhaps the genetic abnormality leads first to keratinocyte hyperproliferation that, in turn, produces a defective skin barrier (p. 10) allowing the penetration by, or unmasking of, hidden antigens to which an immune response is mounted. Alternatively, the psoriatic plaque might reflect a genetically determined reaction to different types of trauma (e.g. physical wounds, environmental irritants and drugs) in which the healing response is exaggerated and uncontrolled. Psoriasis is undoubtedly a genetic condition, but does not follow a simple Mendelian pattern of inheritance. The mode of inheritance is genetically complex, implying a polygenic inheritance. A child with one affected parent has a 14% chance of developing the disease, and this rises to 41% if both parents are affected. Genomic imprinting (p. 343) may explain why psoriatic fathers are more likely to pass on the disease to their children than are psoriatic mothers. If non-psoriatic parents have a child with psoriasis, the risk for subsequent children is about 10%. The disorder is concordant in around 70% of monozygotic (identical) twins but in only 20% of dizygotic ones. There are two peaks of onset of psoriasis. Type I has onset in the second and third decade and a more common family history of psoriasis. Type II has onset in late adulthood in patients without obvious family history. Early onset psoriasis shows a genetic linkage (p. 342) with a psoriasis susceptibility locus (PSOR-1) located on 6p21 within the major histocompatibility complex Class I (MHC-I) region. The HLA-Cw6 allele at this site, which affects immune function, particularly confers a risk of developing psoriasis; 10% of Cw6+ individuals will develop the disease. Corneodesmosin, a protein that is overexpressed in the differentiating outer epidermis of psoriatic skin, is also coded for by a gene here. So too is the coiled-coil alpha helical rod protein-1, which may be involved in regulation of keratinoctye proliferation. Variants of both of these genes are associated with type I psoriasis, but their close proximity to the Cw6 allele, and thus linkage disequilibrium, makes it difficult to conclusively show that they are independent risk factors. The hereditary element and the HLA associations are much weaker in late-onset psoriasis. While PSORS-1 is the most important locus in psoriasis, accounting for up to 50% of genetic susceptibility to the disease, at least 11 other loci (PSORS-2 to 12) have been identified. Variants in the genes for interleukin 23 receptor and interleukin 12B are the most interesting of these with the recent development of effective biological treatments targeted at the p40 subunit common to both cytokines. At present perhaps it is best to consider psoriasis as a multifactorial disease with a complex genetic trait. An individual’s predisposition to it is determined by a large number of genes, each of which has only a low penetrance. Clinical expression of the disease may result from environmental stimuli including antigen exposure. Different forms of psoriasis may well be caused by different underlying gene variants. The epidermis of psoriasis makes itself too fast. Keratinocytes proliferate out of control, and an excessive number of germinative cells enter the cell cycle. This ‘out of control’ proliferation is rather like a car going too fast because the accelerator is stuck, which cannot be stopped by putting a foot on the brake. The growth fraction (p. 7) of epidermal basal cells is increased sevenfold compared with normal skin. This epidermal hyperproliferation accounts for many of the metabolic abnormalities associated with psoriasis. It is not confined to obvious plaques: similar but less marked changes occur in the apparently normal skin of psoriatic patients as well. The exact mechanism underlying this increased epidermal proliferation is uncertain, but the skin behaves as though it were trying to repair a wound. Endothelial cells, and thus blood vessels, proliferate in the superficial dermis in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which is overproduced in psoriatic epidermis. Psoriasis differs from the ichthyoses (p. 45) in its accumulation of inflammatory cells. The importance of T lymphocytes is shown by their presence early in the development of psoriatic plaques and the response of the disease to treatments such as ciclosporin. When non-lesional psoriatic skin is grafted on to severe combined immunodeficient mice, plaques develop more readily following injection of autologous T cells from a psoriatic patient. Defective regulation of the innate immune system is also involved in the development of psoriasis. Psoriatic keratinocytes contain high levels of the antimicrobial peptides LL-37 (cathelicidin), β defensin and psoriasin (S100A7), which may account for the surprisingly low incidence of bacterial skin infection in psoriatic patients. Cathelicidin forms complexes with DNA, and these complexes activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells via Toll-like receptors. Dendritic cells link the innate and adaptive immune systems. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are overexpressed in early psoriatic plaques and on activation produce α-interferon which stimulates myeloid dendritic cells to move to the local draining lymph nodes. Here, the myeloid dendritic cells drive naïve T cells to proliferate and differentiate. Release of interleukin-12 (p. 19) causes differentiation to type 1 helper cells (Th1), and interleukin-23 differentiation to type 17 helper cells (Th17). These T cells are drawn from the circulation back to the psoriatic dermis by the interaction of α1β1 integrin on the T cells with collagen IV at the basement membrane. Once in the dermis, Th1 cells release γ-interferon and TNF-α, and Th17 cells release interleukin-17 and 22. Dendritic cells themselves release further TNF-α and also inducible nitric oxide synthase. This rich cocktail of cytokines acts on keratinocytes, making them proliferate and produce antimicrobial peptides and various chemokines. Neutrophils are drawn to the epidermis by these chemokines, particularly IL-8, producing the characteristic pustules of severe psoriasis. Figure 5.1 The Köbner phenomenon seen after a recent thoracotomy operation. The main changes are the following. Figure 5.2 Histology of psoriasis (right) compared with normal skin (left). Common patterns are as follows. This is the most common type. Lesions are well demarcated and range from a few millimetres to many centimetres in diameter (Figure 5.3). The lesions are pink or red with large centrally adherent silvery-white built-up polygonal scales. Symmetrical sites on the elbows, knees, lower back and scalp are sites of predilection (Figure 5.4). Figure 5.3 Psoriasis: extensive plaque psoriasis. Figure 5.4 Psoriasis favours the extensor aspects of the knees and elbows. This is usually seen in children and adolescents and may be the first sign of the disease, often triggered by streptococcal tonsillitis. The word guttate means ‘drop-shaped’. Numerous small round red macules come up suddenly on the trunk and soon become scaly (Figure 5.5). The rash often clears in a few months but plaque psoriasis may develop later. Figure 5.5 Guttate psoriasis. The scalp is often involved. Areas of scaling are interspersed with normal skin; their lumpiness is sometimes more easily felt than seen (Figure 5.6). Frequently, the psoriasis overflows just beyond the scalp margin. Significant hair loss is rare. Figure 5.6 Untreated severe and extensive scalp psoriasis. Involvement of the nails is common, with ‘thimble pitting’ (Figure 5.7), onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed; Figure 5.8) and sometimes subungual hyperkeratosis. Figure 5.7 Thimble-like pitting of nails with onycholysis. Figure 5.8 Onycholysis. Psoriasis of the submammary, axillary and anogenital folds is not scaly although the glistening sharply demarcated red plaques (Figure 5.9), often with fissuring in the depth of the fold, are still readily recognizable. Flexural psoriasis is most common in women and in the elderly, and is more common among HIV-infected individuals than uninfected ones. Many patients with plaque psoriasis harbour inverse psoriasis in their gluteal folds. Sometimes, when the diagnosis is in doubt, it pays to check for this and for relatively scaleless red papules on the penis. Figure 5.9 Sharply defined glistening erythematous patches of flexural psoriasis. Palmar psoriasis may be hard to recognize, as its lesions are often poorly demarcated and barely erythematous. The fingers may develop painful fissures. At other times lesions are inflamed and studded with 1–2 mm pustules (palmoplantar pustulosis) (Figures 5.10 and 5.11). Psoriasis of the palms and soles may be disabling. Figure 5.10 Pustular psoriasis of the sole. Figure 5.11 A closer view of pustules on the sole. A psoriasiform spread outside the napkin (nappy/diaper) area may give the first clue to a psoriatic tendency in an infant (Figure 5.12). Usually, it clears quickly but there is an increased risk of ordinary psoriasis developing in later life. Figure 5.12 An irritant napkin rash now turning into napkin psoriasis. This is a rare but serious condition, with fever and recurrent episodes of pustulation within areas of erythema. This is also rare and can be sparked off by the irritant effect of tar or dithranol, by a drug eruption or by the withdrawal of potent topical or systemic steroids. The skin becomes universally and uniformly red with variable scaling (Figure 5.13). Malaise is accompanied by shivering and the skin feels hot and uncomfortable. Figure 5.13 Erythrodermic psoriasis. Arthritis occurs in about 5–10% of psoriatic patients. Several patterns are recognized. Distal arthritis involves the terminal interphalangeal joints of the toes and fingers, especially those with marked nail changes (Figure 5.14). Other patterns include involvement of a single large joint; one that mimics rheumatoid arthritis and may become mutilating (Figure 5.15); and one where the brunt is borne by the sacro-iliac joints and spine. Tests for rheumatoid factor are negative and nodules are absent. In patients with spondylitis and sacroiliitis there is a strong correlation with the presence of HLA-B27. Other patients develop painful inflammation where tendons meet bones (enthetitis). Figure 5.14 Fixed flexion deformity of distal interphalangeal joints following arthropathy. Figure 5.15 Rheumatoid-like changes associated with severe psoriasis of hands.

Psoriasis

Cause and pathogenesis

Genetics

Epidermal cell kinetics

Angiogenesis

Inflammation

Precipitating factors

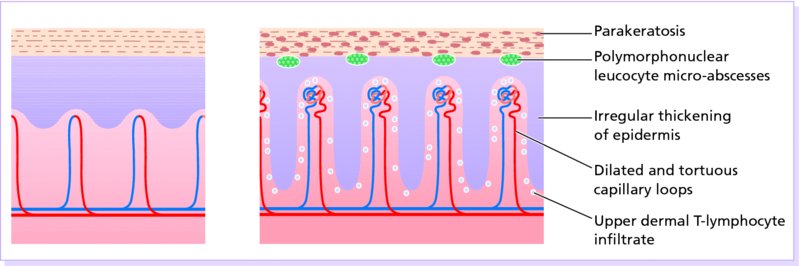

Histology (Figure 5.2)

Presentation

Plaque pattern

Guttate pattern

Scalp

Nails

Flexures

Palms and soles

Less common patterns

Napkin psoriasis

Generalized pustular psoriasis

Erythrodermic psoriasis

Complications

Psoriatic arthropathy

Psoriasis and systemic disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree