Introduction634

INTRODUCTION

AMEBAE

AMEBIASIS CUTIS

Histopathology

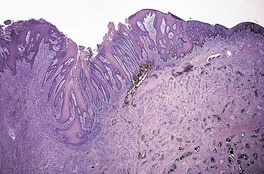

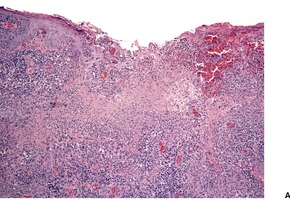

Fig. 27.1

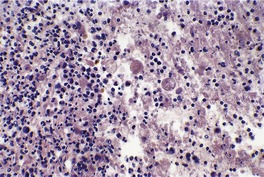

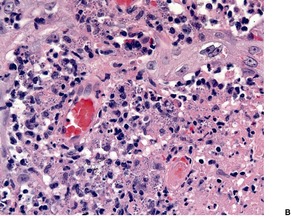

Fig. 27.2

ACANTHAMEBIASIS

Histopathology

FLAGELLATES

TRYPANOSOMIASIS

Histopathology

LEISHMANIASIS

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Histopathology

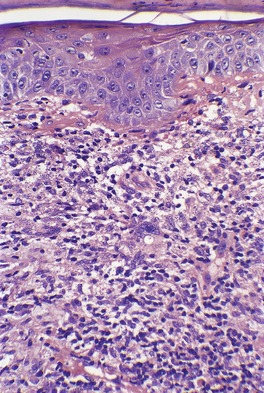

Fig. 27.3

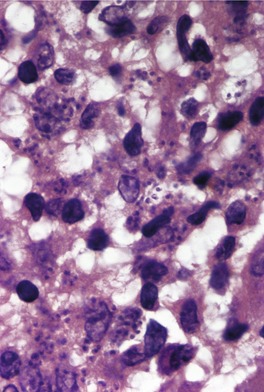

Fig. 27.4

Fig. 27.5

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Histopathology

Visceral leishmaniasis

Histopathology

TRICHOMONIASIS

GIARDIASIS

COCCIDIA

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Histopathology

SPOROZOA

BABESIOSIS

Histopathology

MISCELLANEOUS

PNEUMOCYSTOSIS

Histopathology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Protozoal infections

• Amebae

• Flagellates

• Coccidia

• Microsporidia

• Ciliates

• Sporozoa.

The amebae include the organisms that cause amebiasis and acanthamebiasis. The flagellates constitute an important group that includes the organisms for trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, trichomoniasis, and giardiasis. The coccidia include Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptosporidium parvum; only toxoplasmosis will be considered further. The microsporidia and ciliates include a range of intestinal parasites but no organisms of dermatopathological interest. Finally, the sporozoa include Plasmodium spp. and Babesia spp., responsible for malaria and babesiosis respectively. 1Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) has recently been reclassified as a fungus, but it lacks many of their features. It is considered here by tradition.

Recently, protozoal and other infectious pathogens have been demonstrated in routinely processed paraffin sections with the use of diluted sera from patients with known antibodies to the suspected disease, using an indirect immunoperoxidase technique. 2 The test has a high sensitivity but low specificity.

Amebae are single-celled organisms with trophozoite and cyst stages in the life cycle. Their motility results from pseudopods. The important human pathogen within this group is Entamoeba histolytica. Other species within this genus are non-pathogenic. In recent years there has been an increase in disease caused by other amebae, known as free-living amebae – Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria. 3

Amebiasis is endemic in parts of Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, and Latin America. Visceral amebiasis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in these countries.

Cutaneous infection with Entamoeba histolytica (amebiasis cutis) is quite rare, occurring chiefly in the tropics.4.5. and 6. A recent study of amebiasis cutis from an endemic area in South Africa found 41 patients with cutaneous disease over an 8-year period. 7 It usually develops as a complication of amebic colitis, producing irregular areas of ulceration with verrucous borders around the anus, sometimes spreading to the thighs and genitalia.8.9. and 10. The lesions are usually rapidly progressive and painful. 3 Cutaneous lesions may also arise by fistulous extension from a gastrointestinal or hepatic abscess, around a colostomy or abdominal wound, or as a consequence of venereal transmission. 11 Penile lesions are being seen with increasing frequency in male homosexuals. Cutaneous disease may be the presenting manifestation of undetected visceral amebiasis. 7 It is also commonly associated with HIV infection, particularly in some parts of the world. 7 Cutaneous amebiasis is rare in children. 12

The ulcers are covered by gray slough and have a peculiarly unpleasant smell. Large exophytic lesions resembling squamous cell carcinoma may develop, particularly in genital areas. 13 These lesions may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of carcinoma, with unnecessary surgery being carried out. The author has seen two cases of amebiasis of the penis in which amputation of the organ was performed.

Metronidazole has been used to treat cutaneous disease. 6

Sections usually show an ulcerated lesion with extensive necrosis in the base, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia at the margins, and a non-specific inflammatory infiltrate extending into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissues beneath the ulcer base. 14 In the series from South Africa, referred to above, two fairly distinctive histopathological patterns were observed. About a third of cases were characterized by superficial lesions with the ulceration and inflammation confined to the upper dermis, while the remaining cases had deep lesions extending into subcutis with extensive ‘liquefactive’ necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, numerous trophozoites, and sometimes suppurative foci. 7 The deep variant was associated with visceral disease. 7 Sometimes there is extensive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia involving much of the lesion, with only small punctate areas of ulceration (Fig. 27.1). This may resemble a verrucous carcinoma. E. histolytica may be found, singly and in clusters, in the overlying exudate (Fig. 27.2). They differ from histiocytes by the presence of a single eccentric nucleus with a prominent central karyosome and occasional phagocytosed red blood cells in the cytoplasm. 9 The term hematophagous amebic trophozoites (HATS) has been used for these amebae. 7 In sections of fixed tissue their diameters are usually within the range 12–20 µm, but larger forms up to 50 µm may be seen. 3 They are basophilic. Viable amebae can be highlighted in the necrotic debris by the PAS stain. Degenerate amebae are not enhanced by this stain. 7

Amebiasis of the penis. This case was misdiagnosed on biopsy as a squamous cell carcinoma because of the marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. (H & E)

Amebiasis. Organisms are present in the ulcer base. (H & E)

The free-living amebae of soil and water, Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia, and Naegleria, are facultative parasites of humans.15. and 16. Although meningoencephalitis is the major clinical feature, there have been a number of reports of pustular, chronic ulcerating, nodular, or sporotrichoid lesions in the skin,17. and 18. particularly in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS),19.20.21.22.23. and 24. and in organ transplant recipients.25. and 26.

Cases of fatal amebic encephalitis caused by Balamuthia mandrillaris have been reported.27. and 28. The patients initially presented with an indurated plaque on the face, the biopsy of which was misinterpreted.27. and 28.

Sections have shown tuberculoid granulomatous lesions in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue, often with accompanying vasculitis.17. and 20. In patients with AIDS, granulomas are not always present. There may be a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate with numerous organisms, and abscess formation. A suppurative panniculitis has also been described.21.22. and 24. Amebae, 15–40 µm in width, can often be seen lying free in the tissues; 29 they may take the form of trophozoites or cysts. 22 Organisms are not invariably present in immunocompetent individuals with granulomas.

Of the two cases of Balamuthia that presented with cutaneous lesions, one was misinterpreted by experts from around the world, 28 and the other was initially misdiagnosed, although a subsequent biopsy showed a suppurative and granulomatous process with multinucleated giant cells and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. 27 There was extensive tissue necrosis. Amebic trophozoites were identified in the necrotic tissue and in the walls of small blood vessels. 27

The flagellates are a group of protozoa that move by means of a flagella. They are of considerable medical importance. The following diseases will be considered:

• trypanosomiasis

• leishmaniasis

• trichomoniasis

• giardiasis.

African trypanosomiasis is caused by the protozoa Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, which are transmitted by the bite of the tsetse fly (Glossina species).30. and 31. The Gambian variant has increased in incidence in Central Africa, with nearly 100 000 new infections each year. 31 Although the major clinical manifestations are fever and neurological signs, cutaneous lesions develop in about half of the patients. 32 These lesions consist of an indurated erythematous ‘chancre’ at the site of the bite, followed several weeks later by a fleeting erythematous maculopapular rash, often with circinate forms. 33 The lesions in this latter secondary stage are known as trypanids. 34 The diagnosis is made by finding hemoflagellates in thick peripheral blood smears. 35

American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease), caused by T. cruzi, affects 17 million people in Latin America. 36 It is transmitted by the bite of the triatomine insect species of the family Reduviidae. 36 A transient nodule appears at the site of entry of the protozoa. 37 It causes myocardial disease and intestinal dilatation from damage to the myenteric plexus. 38 Cutaneous disease is very rare and results from reactivation of latent disease in immunosuppressed patients. 39 Clinically, it may cause a large indurated plaque, erythematous papules and nodules, panniculitis, and ulcers. 36

Sections of the chancre show a superficial and deep, predominantly perivascular infiltrate with lymphocytes and many plasma cells, with some resemblance to the lesions of secondary syphilis. 32 Organisms can be seen in Giemsa-stained smears taken from the exudate of a chancre, but they are not usually seen in tissue sections. 32 In the secondary stage the trypanids show mild spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes, a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, and a mild diffuse infiltrate of neutrophils with some leukocytoclasis. 34 Amastigotes of T. cruzi may be present in the epidermis, in walls of blood vessels, in arrector pili muscles, and in the cytoplasm of inflammatory cells in cutaneous lesions of Chagas’ disease. A variable inflammatory cell infiltrate is also present.

Leishmaniasis is an important protozoal infection, with an estimated 1–2 million new cases occurring worldwide each year.40.41.42.43. and 44. Its incidence is increasing, although public health measures in some provinces have led to a decline in those areas.45.46. and 47. Armed operations in Afghanistan and Iraq have given rise to a significant number of cases in troops stationed there.48.49.50. and 51. It is also being seen increasingly in travelers52.53.54.55. and 56. and refugees.57. and 58. It has also been reported in a person in the United Kingdom who had no history of recent travel to an endemic area. 59 A similar case has been reported from Taiwan, a non-endemic country. 60 Leishmaniasis can be classified into three types, each caused by a different species of Leishmania:

1. cutaneous (oriental) leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica in Asia and Africa, and by L. mexicana in Central and South America61

2. mucocutaneous (American) leishmaniasis caused by L. braziliensis

3. visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) caused by L. donovani.

This classification is an oversimplification, as a great deal of clinical overlap exists between the various forms.62. and 63. For example, visceral infection, caused by L. tropica, was reported in American soldiers infected in Saudi Arabia during the operation known as ‘Desert Storm’.64. and 65. A new classification of cutaneous leishmaniasis has recently been proposed. 43 The diagnosis can be made by identifying parasites on histological section, 66 or in smears, 67 by culture on specialized media, by the leishmanin intradermal skin test (Montenegro test), by fluorescent antibody tests using the patient’s serum, 68 or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using species-specific primers. 69 Results of PCR can be falsely positive. 70 The leishmanin test is usually negative in the forms with cell-mediated hyporeactivity, such as the diffuse cutaneous forms and the visceral form (kala-azar). 64

Various subspecies of Leishmania have been documented in recent years (see below). 64 At least 20 species infect humans. Genomic analysis of several species has shown that genes that are differentially distributed between the species encode proteins implicated in host–pathogen interactions and parasite survival in the macrophage. 44

Recently attention has been focused on the role of the immune system and other mechanisms in the elimination of Leishmania.71. and 72. Nitric oxide, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), interleukin-12 (IL-12), and interferon (IFN-γ) also play a role.73.74. and 75.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, a chronic self-limited granulomatous disease of the skin, is usually caused by L. tropica. It is common in children. 43 It is endemic in the Middle East, around the eastern Mediterranean, in North Africa and in parts of Asia.65.76.77.78.79.80.81.82. and 83. The term ‘Old World’ leishmaniasis has been used for such cases. Subspecies of L. tropica include L. major, L. minor, and L. aethiopica.64.84. and 85. Sandflies of the genus Phlebotomus are the usual vectors. The incubation period following the sandfly bite is weeks to months and depends on the size of the inoculum. 86 In Central and South America, and in parts of Texas (‘New World’), L. mexicana is the species involved.87.88. and 89. Subspecies include L. amazonensis, L. pifanoi, and L. venezuelensis.64. and 90. Other species of Leishmania involved in ‘New World’ disease include L. guyanensis and L. panamensis91 as well as L. braziliensis (once considered an exclusive cause of mucocutaneous disease). A recent series of cases caused by this species found mucosal disease in only 12.7% of cases. 92 No cases of mucosal disease were recorded in a series of 71 cases of leishmaniasis from Brazil; in cases tested, all were due to L. braziliensis. 93L. infantum, long considered an exclusive cause of visceral leishmaniasis (see below), has now been identified in cutaneous leishmaniasis.94.95. and 96. These two examples highlight the artificiality of ‘matching’ organisms to each of the three categories (cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral) in the traditional classification.

Acute, chronic, recidivous, disseminated, tardive, and leishmanid forms are recognized.43. and 86. The acute lesions are usually single papules, which become nodules, ulcerate and heal, leaving a scar.76.97.98. and 99. Lesions are usually present on exposed areas of the skin such as the face, arms, and lower legs.100. and 101. The ear is sometimes involved but this site is more commonly affected in forest workers in Mexico and Central America with ‘New World’ disease. 102 The lip and genital region are other sites that can be involved.96.103. and 104. Unusual presentations include paronychial, chancriform, pseudolymphomatous, annular, palmoplantar, zosteriform, and erysipeloid forms.105.106.107.108.109.110. and 111.

Chronic lesions, which persist for 1–2 years, are single, or occasionally multiple, raised non-ulcerated plaques.

The recidivous (lupoid) form consists of erythematous papules, often circinate, near the scars of previously healed lesions.66.112.113.114.115.116.117.118. and 119. The recidivous form is mostly seen with so-called ‘Old World’ leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica. 120 Several cases have now been reported from South America (‘New World’).121. and 122.

The disseminated form (primary diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis) develops in anergic individuals as widespread nodules and macules, without ulceration or visceral involvement.123.124. and 125. It is seen, not uncommonly, in patients with HIV infection.126.127. and 128. Localized lesions may still be seen in patients who are immunosuppressed; lesions are not always disseminated. 129 Reactivation of dormant infection may also occur. 130 The disseminated form is quite rare in L. tropica infections, but less so with L. mexicana.90. and 131. Sporotrichoid,108.132. and 133. psoriasiform, 134 mass, 135 and satellite lesions136. and 137. are very uncommon clinical manifestations of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

A tardive form, in which a lesion developed at the site of recent cutaneous surgery, has been reported. 138 The likely source of infection was encountered over 50 years previously. 138Leishmanid is a very rare form in which eruptions appear in a different site from the primary focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis. 43

A myriad of treatment regimens have been used. A recent report has highlighted the fact that the quality of the treatment studies has generally been poor. 139 Antimonials have long been the backbone of treatment schedules,85.118.140. and 141. with a recent systematic review recording a cure rate of 76.5% with these drugs. 142 Other reports have demonstrated variable outcomes with fluconazole, 48 itraconazole,143. and 144. miltefosine,145. and 146. pentoxifylline, 147 liposomal amphotericin B,148.149. and 150. and vaccines. 151 Therapies such as current field-radio frequency,48.49. and 152. cryosurgery,153. and 154. and photodynamic therapy have been used successfully.155.156. and 157. Cutaneous lesions in patients with HIV infection158 and the disseminated form are much more difficult to treat. 159 Treatment of a patient with localized disease with IFN-γ induced a granulomatous reaction in the lesion. 160 An assessment of the effectiveness of treatment can be made by monitoring the parasite load in skin biopsies using quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. 161

In acute lesions there is a massive dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, parasitized macrophages, epithelioid cells and occasional giant cells, plasma cells, and sometimes a few eosinophils (Fig. 27.3).162. and 163. Both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes are present. 91 Variable numbers of neutrophils are present in the upper dermis. Granulated calcific Michaelis–Gutmann bodies have been reported in the cytoplasm of macrophages in two cases. 164 Rarely, the inflammatory infiltrate extends around small nerves in the deep dermis in a manner similar to leprosy. 165 The parasites are round to oval basophilic structures, 2–4 µm in size. They have an eccentrically located kinetoplast. Their lack of a capsule is helpful in distinguishing them from Histoplasma capsulatum. Although organisms can be seen in macrophages in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (Fig. 27.4), the morphological details are better seen on a Giemsa stain, preferably of a slit-skin smear. 166 Organisms tend to localize at the periphery of the macrophages, the so-called ‘marquee’ sign. The epidermis shows hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, but sometimes atrophy, ulceration, or intraepidermal abscesses (Fig. 27.5).132. and 167. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is present in some long-standing lesions.

Leishmaniasis. The dermal infiltrate is composed of lymphocytes, some plasma cells, and parasitized macrophages. (H & E)

Leishmaniasis. Numerous organisms are present in the cytoplasm of macrophages. (H & E)

Leishmaniasis. (A) An ulcerated lesion in a soldier recently returned from Iraq. (B) Parasitized macrophages are present. (H & E)

With increasing chronicity there is a reduction in the number of parasitized macrophages, and the appearance of small tuberculoid granulomas which consist predominantly of epithelioid cells and histiocytes with occasional giant cells. 167 Central necrosis is rare. 168 There is an intervening mild to moderate mononuclear cell infiltrate. Langerhans cells in the epidermis also decrease with chronicity of the lesions. 169

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is frequently misdiagnosed in countries where it is not endemic, particularly if organisms are not seen. 170 It may be misinterpreted as sarcoidosis, foreign body reaction, granulomatous rosacea, and even granuloma annulare. 170

In the recidivous form the appearances resemble those seen in lupus vulgaris, with tubercles surrounded by lymphocytes and histiocytes with some giant cells.66. and 167. However, there is no necrosis and only sparse plasma cells. Occasional organisms may be found on careful search. The polymerase chain reaction can be used to demonstrate the presence of DNA of Leishmania amastigotes in tissue sections66 or lesional scrapings. 48 It is the most sensitive method for diagnosis.48.74.171. and 172. An immunohistochemical method using a monoclonal anti-Leishmania (G2D10) antibody has been developed. 173 It has only marginally greater sensitivity and specificity than the routine H & E stain.

The initial lesions of mucocutaneous (American) leishmaniasis, caused by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis, resemble those seen in the cutaneous form. 176 In an increasing number of cases, only cutaneous lesions are being seen with this organism (see above).177.178. and 179. Vegetating, verrucous, and sporotrichoid180 lesions may also occur. In up to 20% of cases destructive ulcerative lesions of mucous membranes develop, particularly in the tongue, nasopharynx, and at body orifices.181. and 182. This complication, known as espundia, may develop up to 25 years after the apparent clinical cure of the primary lesion.45. and 176. Mucosal leishmaniasis caused by L. infantum has been reported. 183 Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is found in Central and South America, or in travelers from those areas.184. and 185. The disseminated anergic form is a rare complication; 174 it may occur in patients with AIDS186 or in immunosuppressed individuals. 187

The appearances resemble those seen in the acute cutaneous form, although the number of organisms is considerably smaller and occasional tuberculoid granulomas may be seen. Suppurative granulomas have been described. 176 The mucosal lesions show non-specific chronic inflammation, with only a few parasitized macrophages. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may be prominent in some lesions, particularly at the periphery. 184 There may be fibrosis in the dermis in cicatricial lesions. 184 A favorable prognostic feature is the presence of necrosis with a reactive response. 188

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar), caused by L. donovani, results in fever, anemia, and hepatosplenomegaly. 174 It is endemic in many tropical countries. Cutaneous involvement (post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis) develops in about 5% of cases (10–20% of Indian cases), some 1–3 years or more after the original infection.189.190. and 191. This figure was much higher in a recent series. 192 This cutaneous form is most frequent in countries of the Indian subcontinent.193.194. and 195. The lesions comprise areas of erythema (usually on the face), macules which may be hyper- or hypopigmented (usually on the trunk), 196 and nodules (usually on the face, but not infrequently on the limbs).189.197. and 198. The tongue is rarely involved.58. and 199. A lupoid plaque is a rare manifestation. 200 Lesions may clinically resemble leprosy, but differ by having normal sensation. 192 Coexistence with borderline tuberculoid leprosy has been reported.201. and 202. Cutaneous lesions have recently been reported during the course of visceral leishmaniasis in patients with AIDS;149.203.204.205.206.207.208. and 209. they may develop following HAART-induced immune recovery. 210 Rare variants of AIDS-associated cases have included the occurrence of leishmaniasis in lesions of herpes zoster, 211 parasitization of cells in a dermatofibroma, 212 and the development of dermatomyositis-like lesions. 213

Subspecies within the L. donovani complex include L. donovani, L. infantum, L. chagasi, and L. nilotica. 64

Ketoconazole and allopurinol produce side effects or have a slow response when used in the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. 214 Oral miltefosine has shown promise. 214

There is usually a dense infiltrate of inflammatory cells in the upper dermis beneath an atrophic epidermis. 194 Acanthosis is sometimes present. 215 The infiltrate is composed of a variable admixture of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and epithelioid cells. 216 Occasional eosinophils can usually be found. Neutrophils are present in a few cases. 197 There may be an occasional tuberculoid granuloma. In nodular lesions the infiltrate may occupy the entire thickness of the dermis. 197 In patients with a neuropathy, the inflammatory cell infiltrate shows perineural accentuation. 217 Follicular plugging is often present, particularly in lesions from the face. 194 Organisms (Leishman–Donovan bodies) are nearly always present, but their number varies from case to case and from lesion to lesion. They may be visualized better in sections stained with Weigert iron hematoxylin than in those stained with hematoxylin and eosin or the Giemsa stain. 197 An immunohistochemical method, using G2D10 antibody is a more sensitive method of detecting Leishman–Donovan bodies than H & E section. 218 Immunohistochemistry shows a preponderance of CD3+ T cells. There are few B cells. 215 There are conflicting reports on whether CD4+ cells or CD8+ cells predominate.215. and 219.

Although genital infections with Trichomonas vaginalis are common, cutaneous infections with this organism are exceedingly rare and usually confined to the median raphe of the penis. 220 An underlying cyst or tract is usually present. Trichomonads may be demonstrated by microscopy of the pus, drained from the abscess that forms.

The cutaneous manifestations most commonly associated with gastrointestinal infection by Giardia lamblia are urticaria and angioedema. Other associations have included atopic dermatitis and a papulovesicular eruption that cleared on treatment of the parasite. 221 The protozoan has not been found in skin lesions.

Coccidia have both asexual and sexual cycles. They are usually acquired from contaminated food or water. They are particularly important in immunocompromised patients. They include the genera Cryptosporidium, Sarcocystis, and Toxoplasma. The cat family are the only known definite hosts for the sexual stages of Toxoplasma gondii. They are an important reservoir of infection. Congenital infection is the other important route of transmission.

There are two clinical forms of toxoplasmosis, congenital and acquired.222. and 223. The acquired form is seen most often in immunocompromised patients. 224 Skin changes in both are rare and not clinically distinctive. 225 Macular, hemorrhagic, and even exfoliative lesions have been reported in congenital toxoplasmosis, 226 whereas in the acquired form the lesions have been described as maculopapular, hemorrhagic, lichenoid, 227 nodular, and erythema multiforme-like.226. and 228. There have been several reports of a dermatomyositis-like syndrome.229. and 230. The report of acute toxoplasmosis presenting as erythroderma231 has subsequently been challenged. 232

There is a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. In about half the cases parasites can be seen in the cytoplasm of macrophages, in the form of pseudocysts, or lying free in the dermis, 228 or rarely the epidermis, 224 in the form of trophozoites. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may develop in a few cases. 228 The histology has resembled dermatomyositis in those cases presenting with a dermatomyositis-like syndrome. Some of the rare histological expressions of the disease have recently been reviewed. 233

The sporozoa include Plasmodium spp. and Babesia spp., the organisms that cause malaria and babesiosis respectively. Only babesiosis will be considered further.

Babesiosis is a rare protozoal zoonosis caused by a hemoprotozoan of the genus Babesia. 234 It is transmitted by the bites of ticks of the genus Ixodes. 234 Few cases of human babesiosis have been reported, but most cases of the disease go unreported or undetected. 235 It is seen particularly in patients who are immunosuppressed or have undergone splenectomy. It may be transmitted by blood transfusions. 235

In the United States, most cases have been in the northeast and mid-west. Babesia microti is usually involved. In Europe, B. divergens has caused most cases, particularly in asplenic patients. Onset of the disease is insidious, often with mild flu-like symptoms. Cutaneous lesions are rare. An annular erythema with some resemblance to necrolytic migratory erythema has been reported. 234

The patient with the annular erythema referred to above had histopathological features said to be compatible with necrolytic migratory erythema. There was subcorneal pustulation with adjacent parakeratosis, but the vacuolated keratinocytes reported were difficult to see in the published photomicrograph. 234 Dermal inflammatory changes were superficial and mild.

Although traditionally classified as a protozoan, Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly P. carinii) has recently been reclassified as a fungus on the basis of several morphological features. Pneumocystosis is considered here by tradition.

Cutaneous pneumocystosis is a rare infection in patients with AIDS.236. and 237. There may be polypoid lesions in the external auditory canals, or necrotic papules and nodules elsewhere on the skin. 237

Sections show perivascular mantles of amphophilic, foamy to finely stippled material similar to that seen in pulmonary pneumocystosis. 236 The methenamine silver stain may show large numbers of small cysts typical of Pneumocystis jiroveci. The other two structural forms of P. jiroveci, the intracystic sporozoite and the trophozoite (the encysted form), may be seen with polychrome stains such as the Giemsa or Wright stain. 237

References

Introduction

1. Javed, MZ; Srivastava, M; Zhang, S; Kandathil, M, Concurrent babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in an elderly host, Mayo Clin Proc 76 (2001) 563–565.

2. Tsutsumi, Y, Histopathological diagnosis of infectious diseases using patients’ sera, Semin Diagn Pathol 24 (2007) 243–252.

Amebae

3. Magaña, M; Magaña, ML; Alcántara, A; Pérez-Martín, MA, Histopathology of cutaneous amebiasis, Am J Dermatopathol 26 (2004) 280–284.

4. El-Zawahry, M; El-Komy, M, Amoebiasis cutis, Int J Dermatol 12 (1973) 305–307.

5. Parshad, S; Grover, PS; Sharma, A; et al., Primary cutaneous amoebiasis: case report with review of the literature, Int J Dermatol 41 (2002) 676–680.

6. Al-Daraji, WI; Ilyas, M; Robson, A, Primary cutaneous amebiasis with a fatal outcome, Am J Dermatopathol 30 (2008) 398–400.

7. Ramdial, PK; Calonje, E; Singh, B; et al., Amebiasis cutis revisited, J Cutan Pathol 34 (2007) 620–628.

8. Binford, CH; Connor, DH, Amebiasis, In: Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases (1976) Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, pp. 308–316.