Introduction574

TREPONEMATOSES

SYPHILIS

Congenital syphilis

Primary syphilis

Histopathology

Secondary syphilis

Histopathology

Fig. 24.1

Fig. 24.2

Fig. 24.3

Fig. 24.4

Fig. 24.5

Fig. 24.6

Latent syphilis

Tertiary syphilis

Histopathology

ENDEMIC SYPHILIS (BEJEL)

YAWS

Histopathology

Fig. 24.7

Fig. 24.8

PINTA

Histopathology128

BORRELIOSES

ERYTHEMA MIGRANS

Histopathology

ACRODERMATITIS CHRONICA ATROPHICANS

Histopathology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Spirochetal infections

The treponematoses are caused by infection with the spirochete Treponema pallidum and its various subspecies. They include:

• syphilis

• endemic syphilis (bejel)

• yaws

• pinta.

The treponemes responsible for these different diseases are currently indistinguishable on morphological and routine serological grounds, although different names have been given to the various subspecies responsible for each condition; the various subspecies may differ by as little as a single nucleotide. This finding suggests that these organisms have evolved from a common ancestor. The organism cannot be cultivated and maintained on artificial media. 1

Syphilis is usually acquired by sexual (venereal) transmission, while the other conditions are contagious and endemic to various countries.

The clinical features of the treponematoses can usually be divided into distinct stages, reflecting initial local infection with the organism, followed by dissemination and the subsequent host response. Serology is usually used to confirm the diagnosis of a treponemal infection. 2

Other species of Treponema are found in humans: some species are found in the mouth and may be responsible for periodontal disease; others may be found in the sebaceous secretions of the genital region. There is no known clinical significance of these genital treponemes.

The pathogenic mechanisms that give the treponeme its virulence are poorly understood. The organism possesses no secretory apparatus that would deliver virulence factors into the host tissues. 3 One possible mechanism is its ability to stimulate human fibroblasts to increase the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) which is capable of degrading the surrounding connective tissue. 3 Furthermore, the presence of acid repeat proteins (arp) in the genome make it highly immunogenic. They may play a part in the pathogenesis of the disease; they are also potential vaccine candidates. 1

Syphilis is an infectious disease of worldwide distribution, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum.4.5.6. and 7. Its genome was sequenced in 1998. 8 Although its incidence decreased in the 1980s as a consequence of safer sexual practices resulting from the emergence of the HIV epidemic, since the mid-1990s it has once again emerged as a clinical problem, particularly in men who have sex with other men.9.10.11. and 12. The mode of infection is almost always by sexual contact and, consequently, seropositivity for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is sometimes present in individuals with active syphilis.13.14.15. and 16. Non-sexual transmission (syphilis brephotropica) occurs, rarely, in children from infected parents. 17 Congenital infection is also quite rare, although its incidence appears to be increasing.18.19.20.21. and 22. Acquired syphilis may be considered in four stages: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary. 23 Congenital syphilis will be considered before the acquired forms.

Congenital syphilis, which usually results from the transplacental infection of the fetus from an infected mother, has been divided into early, in which clinical manifestations are seen in the first 2 years of life, but mostly in the first 3 months, and late forms. 24 Prematurity, low birthweight, rhinorrhea, and mucocutaneous lesions are typical clinical findings of the early form. The nephrotic syndrome is uncommon. 25 The skin lesions are varied and include a macular rash, vesiculobullous or scaling lesions, predominantly on the palms and soles,26. and 27. and condylomata lata. Erythema multiforme and diffuse alopecia have also been reported.28. and 29.

The initial lesion of syphilis – the primary chancre – is an indurated painless ulcer with a sharply defined edge that often is surrounded by an inflammatory zone. It is usually found on genital or perianal skin, although about 5% of chancres are extragenital.32.33.34.35. and 36. The nipple is one such site. 37 The chancre appears approximately 21 days after sexual exposure. In patients with HIV infection, multiple or more extensive chancres are sometimes present. 15 The serous exudate from the ulcer generally contains numerous treponemes, which can be identified by dark-ground microscopy.

In time the ulcer heals, leaving a small stellate or nondescript scar. The chancre is often accompanied by painless enlargement of the regional lymph nodes.

The epidermis at the periphery of the chancre shows marked acanthosis, but at the center it becomes thin and is eventually lost. The base of the ulcer is infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells, particularly adjacent to the blood vessels, in which there is prominent endothelial swelling. The treponemes can usually be demonstrated by appropriate silver impregnation techniques, such as the Levaditi or Warthin–Starry stains. The May–Grünwald–Giemsa technique can also be used to demonstrate organisms. 38 PCR-based methods may be used on paraffin-embedded skin biopsy specimens to confirm the presence of the organism. 39 On dark-field examination of a smear from a chancre the Treponema pallidum can be seen as a thin, delicate spiral organism 4–15 µm in length and 0.25 µm in diameter. Electron microscopy has shown T. pallidum to be principally in the intercellular spaces in the vicinity of small blood vessels, as well as in macrophages, endothelial cells, and even plasma cells. 40 Collagen fibers appear to be damaged by the treponeme. 41

In untreated cases the multiplication of the widely dispersed treponemes results in secondary syphilis, some 4–8 weeks after the chancre. Besides the mucocutaneous lesions there may be constitutional symptoms, which include fever, lymphadenitis, and hepatitis.42. and 43. A self-limited febrile reaction (the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction), accompanied by systemic symptoms, may occur following the commencement of antibiotic therapy for syphilis. 44

The cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis45 are usually maculopapular or erythematosquamous, somewhat psoriasiform lesions, but lichenoid, 46 nodular,47.48.49.50. and 51. corymbose, 52 annular, 53 annular verrucous, 54 bullous, 55 follicular, 56 pustular, rupial, and ulcerative57.58.59.60. and 61. lesions may develop. Secondary syphilis has presented as scrotal eczema. 62 Atypical clinical presentations, including seronegativity,63. and 64. may occur in patients with coexisting HIV infection.15.65.66.67. and 68. Furthermore, an accelerated progression through the various stages of syphilis can occur in these patients. The term ‘lues maligna’ has been applied to the nodulo-ulcerative and necrotic lesions that can occur when there is concurrent HIV infection,69.70. and 71. although HIV infection is not invariably present. 72 The lesions of secondary syphilis may mimic a wide variety of skin diseases. Pruritus is only occasionally present. 73 Large, fleshy, somewhat verrucous papules (condylomata lata) may develop in the anogenital region and/or intertriginous areas: 74 these should not be confused with viral condylomata acuminata (see p. 624). A moth-eaten alopecia (alopecia syphilitica) is a characteristic manifestation of secondary syphilis.75.76. and 77.

Isolated oral lesions are rare in secondary syphilis; they are typically painful and multiple. 78 A patient with a lesion on the tongue resembling oral hairy leukoplakia has been reported. 79

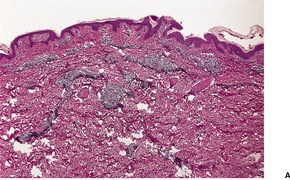

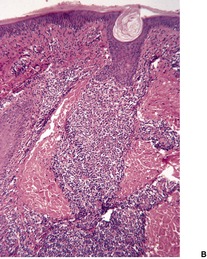

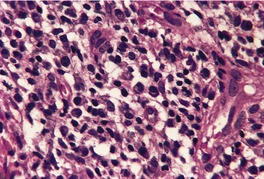

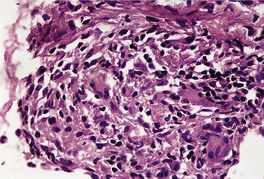

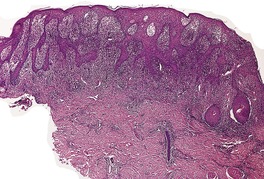

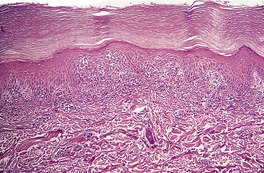

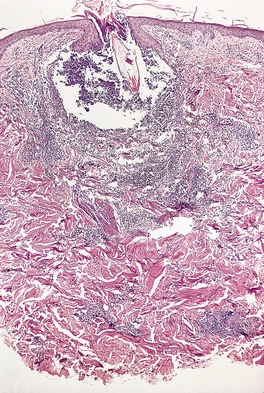

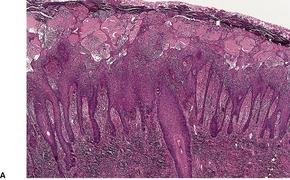

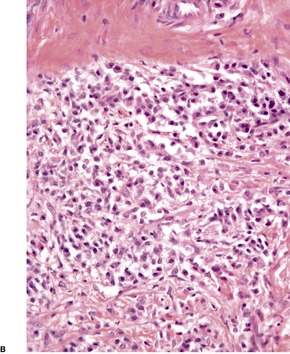

There is considerable variation in the histological pattern.43.80.81. and 82. Plasma cells may be absent or sparse in up to one-third of all biopsies, and the vascular changes may not be prominent. The infiltrate usually involves both the superficial and the deep dermis, except in the macular lesions, where it is more superficial (Fig. 24.1). Perineural plasma cells are relatively common. 83 Extension of the inflammatory infiltrate into the subcutis is uncommon. 43 The infiltrate is predominantly lymphocytic, with some histiocytes and variable numbers of plasma cells (Fig. 24.2). The histiocytic cells express both CD4 and CD14, while the majority of lymphocytes are CD8+. 84 Plasma cells are less numerous in macular lesions. 85 Angiogenesis is common. 86 Early lesions often show a neutrophilic vascular reaction, which is presumed to be related to immune complex deposition. 87 A heavy neutrophil infiltrate resembling that in Sweet’s syndrome has been reported. 88 Follicles and sweat glands may be sleeved by inflammatory cells. 80 In alopecia syphilitica, a lymphoid infiltrate around hair follicles and follicular keratotic plugging are almost invariable.75. and 76. Peribulbar lymphoid aggregates may be present. 75 Immunohistochemical studies have shown the presence of T. pallidum limited to the peribulbar region and penetrating into the follicle matrix. 89 Sometimes the dermal infiltrate in secondary syphilis is dense and diffuse, and it has been likened to cutaneous lymphoma,90. and 91. although its heterogeneous nature is against lymphoma. Approximately 5–10% of the cells may be CD30+. 92 A granulomatous pattern may also be seen in secondary syphilis, 93 particularly after about 16 weeks of the disease. 80 Epithelioid granulomas may be found in late secondary syphilis (Fig. 24.3), and there is a report of a palisading granuloma similar to that seen in granuloma annulare. 94 Perineural granulomas simulating leprosy may be present. 95 Sarcoidal granulomas are rare. 49 The epidermis is frequently involved. It may show acanthosis with spongiosis, psoriasiform hyperplasia, and spongiform pustulation, with considerable exocytosis of neutrophils (Fig. 24.4). 81 A lichenoid tissue reaction may be present, particularly in late lesions (Fig. 24.5). 96 In the rare ulcerative form there is necrosis of the upper dermis, 59 whereas in the follicular type there is microabscess formation in the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, or a follicular pustule (Fig. 24.6). There may be perifollicular granulomas. 56 Condylomata lata have marked epidermal hyperplasia and a dermal infiltrate which is similar to that seen in other lesions of secondary syphilis. T. pallidum may be identified in tissue sections using silver stains such as the Warthin–Starry stain, or by immunoperoxidase techniques. 97 The latter are more sensitive than silver stains, 98 with a sensitivity of 71% in one study compared to 41% for the silver stain. 83 Organisms are found in the dermis more often than the epidermis using immunohistochemistry. 83 The molecular detection of Treponema pallidum, using PCR-based techniques, is likely to become the ‘gold standard’.39. and 99.

(A) Secondary syphilis. (B) There is a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate in the dermis. (H & E)

Secondary syphilis. The perivascular infiltrate of inflammatory cells includes some plasma cells. (H & E)

Late secondary syphilis. A small, non-caseating granuloma is present in the dermis. (H & E)

Late secondary syphilis. There is psoriasiform hyperplasia and mild spongiosis. (H & E)

Late secondary syphilis. A lichenoid (interface) reaction is present. (H & E)

Secondary syphilis. A follicular pustule of secondary syphilis. (H & E)

Subepidermal vesicles have been reported, uncommonly, as a manifestation of the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction. 44 The bullae reported in a case of bullous secondary syphilis were also subepidermal. 55

Even without treatment, the manifestations of secondary syphilis subside spontaneously. During this phase there are no signs or symptoms, although there is a tendency for cutaneous lesions to relapse in the first few years after the disappearance of the lesions of secondary syphilis. Serology is usually positive, but screening tests may be negative in patients with HIV infection. 102 Syphilis incognito is a variant of latent syphilis in which there has been no clinical evidence of a preceding primary or secondary stage. 103

There are two types of cutaneous lesion in tertiary syphilis: one is nodular and the other a chronic gummatous ulcer.104. and 105. They are usually solitary. 106 The nodular form presents an undulating advancing border of red-brown scaly nodules, some of which may become ulcerated. 107 Lesions may mimic granuloma annulare. 108 The gummatous form starts as a deep, firm swelling that eventually breaks down to form an ulcer.

The gummas of tertiary syphilis have large areas of gummatous necrosis with a peripheral inflammatory cell infiltrate which includes lymphocytes, macrophages, giant cells, fibroblasts, and plasma cells. The giant cells are often of Langhans type. There is usually prominent endothelial swelling and sometimes proliferation involving small vessels. Attempts to demonstrate T. pallidum by silver staining techniques are usually unrewarding, although indirect immunofluorescence and PCR-based assays have been used with success.99. and 109. The nodular or tuberculoid lesions show hyperkeratosis, often overlying an atrophic epidermis. There is a superficial and deep mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate, which usually includes plasma cells and tuberculoid granulomas. 110 Plasma cells may be sparse in an occasional case. 111

Brief mention will be made of endemic syphilis (non-venereal syphilis, bejel), a contagious disease found in parts of the Middle East, particularly the Euphrates Valley.112.113. and 114. It is caused by an organism Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum closely related to Treponema pallidum; accordingly serological tests for syphilis are positive. 115 The disease has virtually been eradicated following public health measures initiated by the World Health Organization. Primary, secondary, and tertiary stages have been described. 115 A primary lesion is rarely detected because of its small size and location within the oral and nasopharyngeal mucosa, but otherwise the clinical and pathological manifestations resemble those of yaws in many respects (see below). The main features are ‘mucous patches’ in the mouth and pharynx, as well as cutaneous and bone lesions.

Yaws, or frambesia, is a tropical non-venereal infection caused by Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue (Treponema pertenue), an organism that has hitherto been indistinguishable from Treponema pallidum.116.117.118. and 119. Hybridization studies now suggest that the subspecies pertenue differs from the subspecies pallidum by a single nucleotide. 113 However, no serological test will differentiate yaws from syphilis, although slightly different lesions are produced when the respective organisms are inoculated into hamsters or rabbits. 119 The distinction is largely clinical, with some assistance from the histopathology. Yaws is contracted usually in childhood and spreads by direct contact, perhaps aided by an insect vector. 117 Despite successful eradication after World War Two, yaws is now returning in some tropical countries.116.119.120.121. and 122. It is seen in Central and West Africa, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Pacific Islands, particularly Vanuatu.115. and 123. An eradication program in India appears to have been successful. 124 Reports of treatment failures using penicillin have been reported, 125 but it remains the treatment of choice for yaws.

The primary papule, usually on the legs or buttocks, begins 2–4 weeks after inoculation. It develops into a chronic ulcerating papillomatous mass that may persist for months. 113 The secondary stage is characterized by similar, widespread exuberant lesions covered with a discharge. In warm moist areas, such as mucocutaneous junction areas, large condylomatous lesions may develop. 116 Hyperkeratotic plaques form on the palms and soles (‘crab yaws’). Periods of exacerbation and quiescence occur over the next few years, followed by a longer latent phase, which precedes the development of the tertiary phase. It consists of chronic gummatous ulcers that occur on the central face or over long bones, often with involvement of the underlying bones. Hyperkeratosis and fissuring of the soles and palms frequently recur. 115 Apart from the bone lesions there is no systemic involvement.

The appearances of the primary and secondary lesions are similar. There is usually prominent epidermal hyperplasia, which is usually of pseudoepitheliomatous rather than psoriasiform type, with overlying scale crust and superficial epidermal edema (Fig. 24.7). There are intraepidermal abscesses and a heavy superficial and mid-dermal infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and often a few eosinophils. The neutrophils are more prominent superficially. Blood vessels show minimal endothelial swelling. The ulcerative lesions resemble those of syphilis.

Yaws. (A) Note the epidermal hyperplasia and edema of the superficial epidermis. (B) There are many plasma cells in the infiltrate. (H & E)

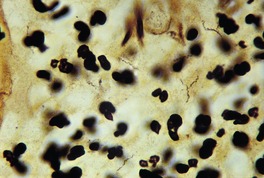

The spirochete of yaws, like that of pinta, is most often demonstrated by silver techniques in the epidermis, in contrast to that of syphilis, which is found in the upper dermis (Fig. 24.8).

Yaws. Numerous fine spirochetes are present. (Warthin–Starry ×1500)

Pinta (carate) is a contagious non-venereal treponematosis caused by Treponema pallidum subsp. carateum (Treponema carateum), which is morphologically identical to Treponema pallidum. Direct skin-to-skin contact is the method of transmission. The disease occurs in the Caribbean area, Central America, and parts of tropical South America.113.114.126. and 127. It appears to be declining in incidence. It affects mainly children and young adults. 123 The lesions of pinta are confined to the skin and become very extensive. There is often overlap between the three clinical stages. Initial lesions are erythematous maculopapules, which grow by peripheral extension and often coalesce. The secondary lesions are widespread, long-lasting scaly plaques that show a striking variety of colors – red, pink, slate blue, and purple. These lesions merge with the late stage, in which depigmentation resembling vitiligo occurs, and sometimes epidermal atrophy.

The treatment of choice is benzathine penicillin G. Alternative therapies, as in other treponematoses, are tetracycline or erythromycin. 123

Primary and secondary lesions are identical and show hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis. There is exocytosis of inflammatory cells, sometimes with intraepidermal abscesses. Hypochromic areas show loss of basal pigmentation with numerous melanophages in the upper dermis. The dermal infiltrate, like the other changes, is heavier in established than in early lesions, and includes lymphocytes, plasma cells, and sometimes neutrophils. The infiltrate is predominantly superficial and perivascular. The treponemes can be demonstrated by silver methods: they are present mainly in the upper epidermis and are seldom, if ever, found in the dermis.

The borrelioses are an important group of spirochetal infections, found particularly in the temperate zones of Europe, North America, and Asia. More than 100 000 cases have been recorded from the United States alone. 129 Unlike the treponematoses, which have no known animal reservoir, the borrelioses are an arthropod-borne infection, usually involving ticks of the genus Ixodes. Three genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi have been identified as human pathogens: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii. The genetic diversity of this species complex is considerable with more than 100 different strains identified in the United States and over 300 worldwide. 130 Although not known for certain, it is possible that different strains may be associated with different clinical manifestations. 130B. burgdorferi is the only pathogenic genospecies in North America, explaining the rarity in that region of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, for which B. afzelii is the predominant, but not exclusive, etiological agent. 131

The borrelioses are not endemic in Australia. Occasional cases of Lyme disease are seen in travelers returning to Australia, particularly from Europe. Australia does not have the species of ticks responsible for the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi in other countries. Rarely, patients present with clinical features suggestive of an atypical borreliosis who have never left Australia. The author has been shown two such cases in which spirochetes appeared to be present in tissue sections of a skin biopsy from such patients. Serology for Borrelia was negative using international criteria. It has been suggested that a so-far undiscovered spirochete may be responsible for these Australian cases. If such an organism exists, the disease it produces shares few of the epidemiological or clinical characteristics of Lyme disease as seen in Europe and the United States. 132

Borrelia are involved in the following conditions:

• erythema migrans

• acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

• Borrelia-associated lymphocytoma cutis

• Borrelia-associated B-cell lymphoma.

It has been suggested that progressive facial hemiatrophy (Parry–Romberg disease) may be a borreliosis but this suggestion has not yet been confirmed by others. 133

Borrelia burgdorferi has also been identified in several of the diseases of collagen, including eosinophilic fasciitis (borrelial fasciitis), 134 morphea, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, and atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. 135 These conditions appear to have other etiologies as well; accordingly, they are discussed in Chapter 11, pages 304–316. Using focus floating microscopy, a new and sensitive technique for detecting Borrelia species in tissue sections (see below), spirochetal microorganisms have been detected in cases of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma.136. and 137. Orofacial granulomatosis and the Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome do not appear to be caused by Borrelia.138. and 139.

Although most borrelioses result from arthropod-borne infections, transplacental transmission of the organism can also occur; no distinct pattern of teratogenicity has been recorded. 140 Infection with Borrelia has been reported in a few HIV-infected individuals but it remains unknown whether the concurrent infection alters the disease as it does with another spirochetosis, syphilis. 141

Real-time PCR has been used to detect Borrelia in blood samples. 142

Erythema migrans, formerly known as erythema chronicum migrans, is the distinctive cutaneous lesion of the multisystem tick-borne spirochetosis Lyme disease (named after the community in Connecticut, USA, where many cases were originally recognized).129.143.144.145.146. and 147. From 20% to 50% or more of the patients have extracutaneous signs or symptoms which may involve the joints, nervous system, and heart.148.149.150. and 151. The cutaneous lesion is a centrifugally spreading erythematous lesion at the site of the bite of the tick, Ixodes scapularis (Ixodes dammini), or other species such as I. ricinus in Great Britain.147. and 152. The annular lesion, which measures 5–20 cm in diameter, develops within 3 months of the tick bite (average 9 days). 153 It can be confused clinically with other annular dermatoses. 154 Uncommonly, the primary lesion may be vesicular. 155 The risk of infection appears to be low if the tick has been attached for less than 24 hours. 156 Lesions are multiple in up to 25% of cases.143.157. and 158. These other lesions (secondary erythema migrans) result from hematogenous dissemination of the organism. 159 Immunosuppression does not appear to influence the clinical presentation (other than the site of lesions), response to therapy, or production of antibodies to Borrelia. The trunk is the favored site of lesions in immunosuppressed patients and the legs in immunocompetent patients. 160

There has been recent debate on the appropriate nomenclature for the various manifestations of this borreliosis. ‘Erythema migrans’ should be used for the cutaneous lesion(s) and ‘Lyme disease’ for the multisystem disease, usually associated with multiple skin lesions, resulting from blood-borne disease.161. and 162.

All three genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi have been isolated from the vector and from some patients with Lyme disease,161.163.164. and 165. and antibodies and lymphoproliferative responses to it have been found in the sera of patients with the disease.166.167. and 168. Confirmation of B. burgdorferi infection is still only found in about 30% of the presumptive cases. 129 Even 40% of culture-positive cases remain seronegative. 169 The diagnosis of erythema migrans is often made by PCR performed on paraffin-embedded biopsy material, 170 although culture is also an important diagnostic tool. 154 Focus floating microscopy (see below) has been mentioned as the new ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis. 171 The organism usually disappears from lesional skin after treatment with various antibiotics such as doxycycline and the synthetic penicillins.172.173. and 174. Antibiotics appear to prevent or limit long-term complications such as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. 175 Antibody titers are inappropriate for the assessment of therapeutic response as they may persist if the initial skin lesion was large. 176 The organisms may be isolated using BSK-II (Barbour–Stoenner–Kelly) medium.153.177. and 178.

Various methods have been proposed for the prevention of Lyme disease. 179 A vaccine is currently the only empirically demonstrated method to prevent it. 179 Doxycycline therapy following a tick bite appears to have limited success. 180

Further studies are required to determine the exact cause of the erythema migrans-like rashes associated with bites of the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum). It is possible that the bites of this tick transmit other, as yet unidentified, spirochetes. 181

There is a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, sometimes with abundant plasma cells and eosinophils. 182 Plasma cells are an inconsistent finding. 170 Eosinophils are only prominent adjacent to the site of the initial tick bite. 129 Rarely there are scattered neutrophils. In more than half of the cases the infiltrate extends into the subcutis. The dermal infiltrate can be equally sparse or moderately dense to dense. 170 When heavy, the infiltrate is more likely to involve the subcutis. Pseudolymphomatous features with germinal centers are uncommon. Interstitial histiocytes (CD68+) are common and perivascular dendritic cells much less frequent. 170 Epidermal changes include spongiosis, vacuolar change, apoptotic keratinocytes, and lymphocyte exocytosis. 170 With the Warthin–Starry silver stain a spirochete can be found in nearly half of the specimens in the papillary dermis near the dermoepidermal junction.183.184. and 185. The diagnosis requires an index of suspicion based on the clinical features. The small size of the organism places some limits on its identification using conventional microscopic techniques. 178 The diagnosis has also been confirmed using an indirect immunofluorescence technique with a monoclonal antibody to the axial filaments of several Borrelia species. 186 Monoclonal antibodies can also be used in immunoperoxidase techniques. A technique that uses PCR allows the molecular detection of B. burgdorferi in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lesions of this condition.170.187. and 188.

Focus floating microscopy (FFM) has been described recently as the new ‘gold standard’ for the diagnosis of cutaneous borreliosis. 171 It detected organisms in 30 of 32 cases of erythema migrans. This immunohistochemical method involves staining sections with a B. burgdorferi antibody and then simultaneously scanning sections through two planes, using standard histological equipment. 171 FFM ‘scans through the sections in 2 planes: horizontally in serpentines as in routine cytology and, simultaneously, vertically by focusing through the thickness of the cut (usually 3–4 µm)’. 171

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is a chronic/late manifestation of infection by a genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi. B. afzelii is the predominant, but not exclusive, etiological agent. 131 The condition is most often reported from northern, central and eastern Europe, but not from North America, where B. afzelii is not endemic.165.189.190. and 191. In one report from an endemic area of borreliosis in northern Italy, it was found in 2.1% of patients who had Lyme borreliosis. 192 There are reports of this condition being preceded by erythema migrans.

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans usually occurs in the elderly and is rare in childhood.193.194.195. and 196. The diagnosis is often delayed in children. 195 There is a predilection for females. Clinically, there is an initial inflammatory stage characterized by diffuse or localized erythema, which gradually spreads to involve the extensor surfaces of the extremities and areas around joints.189. and 197. After some months there is gradual atrophy of the skin, with loss of appendages and often hypopigmentation. Areas resembling lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, sclerodermatous patches, and linear fibrotic bands over the ulna and tibia may also be found. In addition, juxta-articular fibrous nodules may develop in 10–25% of cases of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans;198. and 199. they regress rapidly under antibiotic therapy. 200 Neuroborreliosis may result in callosities and plantar ulcers with associated peripheral neuropathy. 196

B. afzelii DNA has been identified in cutaneous lesions, using PCR, and by culture.201. and 202. The organisms are able to invade endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and Langerhans cells and to survive in collagenous tissue causing tissue damage, resulting in acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. 202

Various mechanisms have been postulated to explain why borreliae can survive in the collagen for months or years despite the presence of high antibody titers against the organism and the presence of CD4-positive T lymphocytes. The significant down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on epidermal Langerhans cells in both early and late stages of Lyme borreliosis indicates a poorly effective immune response and may partly explain the faulty elimination of the organisms from the skin.202. and 203. A recent study has shown a restricted pattern of cytokine expression in this condition. Whereas interferon-γ is produced in lesions of erythema migrans, it is lacking in acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. 204 This cytokine may play a role in spirochetal killing. 204

The early stages of the disease show a superficial and deep chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis which is moderately heavy and composed predominantly of lymphocytes with some histiocytes and plasma cells. There is often accentuation around blood vessels, which may show telangiectasia, and also around adnexae. Sometimes there is a superficial band-like infiltrate of inflammatory cells with a thin zone of collagen separating the inflammatory cells from the basal layer. Scattered vacuoles or groups of vacuoles that morphologically resemble fat cells (but which do not appear to stain for fat – pseudolipomatosis cutis) have been reported in the upper dermis in some cases (see p. 848). 189 As the lesions progress there will be atrophy of the dermis to about half its normal thickness or less (Fig. 24.9). This is usually accompanied by loss of elastic fibers and pilosebaceous follicles, atrophy of the subcutis, and variable epidermal atrophy with loss of the rete pegs. 190