RECONSTRUCTIVE GOALS

I. PATIENTS UNDERGOING HEAD AND NECK RECONSTRUCTIVE PROCEDURES ARE OFTEN DEBILITATED, AND LONG-TERM SURVIVAL MAY BE POOR. Many cancer patients must also undergo postoperative radiation or chemotherapy. Therefore, the goal is rapid reconstruction with optimization of function and low morbidity, accomplished as a one-stage procedure whenever possible.

II. A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH IS NECESSARY IN PATIENTS WITH HEAD AND NECK CANCER. The reconstructive surgeon is part of a team that includes medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists, pathologists, nutritionists, and psychiatrists, and (if needed) speech therapists, dentists, and ophthalmologists.

III. IN ADDITION TO STANDARD RECONSTRUCTIVE CONCEPTS, SPECIFIC PRINCIPLES GUIDE HEAD AND NECK RECONSTRUCTION PLANNING

A. Attempt to restore symmetry

B. Maintain structural integrity of the nose and ears, for both aesthetic and functional reasons (e.g., support for glasses, nasal airflow).

C. Maintain competence of the oral and ocular openings, with particular attention paid to the risk of late scar contractures.

D. Replace entire anatomic subunits when reconstructing larger defects for the best aesthetic outcome.

E. Maintain or restore independent speech, breathing, and swallowing functions whenever possible.

RECONSTRUCTION BY ANATOMIC REGION

I. CUTANEOUS DEFECTS OF THE HEAD AND NECK (See Section “Facial Reconstruction”)

II. THE MIDFACE

A. Goals

1. Restore the contour and projection of the region.

2. Recreation of the maxilla and the occlusive surfaces.

3. Separation of the oral and nasal cavities.

4. Provide support for the eye or a prosthetic replacement.

5. Maintain flow through the lacrimal system.

B. Prosthetics historically have been used extensively in the midface, either alone or in combination with tissue transfers. Maxillectomy defects that do not involve the buttresses or the orbits can be managed effectively with a palatal obturator.

C. Regional flaps: The deltopectoral flap, the temporalis muscle flap, and the forehead flap can be used to address medium-sized defects.

D. Non-vascularized bone grafts: Used to fill bony gaps. The graft must be covered with adequate well-vascularized tissue and be rigidly fixed in position for success.

______________

*Denotes common in-service examination topics

1. The radial forearm osteocutaneous flap: A vascularized piece of radius up to 10 cm in length can be harvested with the flap and used for bony support.

2. Scapular osteocutaneous flaps, with or without a skin paddle, may include a portion of the latissimus muscle. They are based either on the descending or on the transverse branches of the circumflex scapular artery and the angular branch thereof.

3. Free fibula, rectus abdominis muscle, or omental flaps may also be useful in the midface.

III. THE MANDIBLE

A. Goals:

1. Restore facial contour

2. Maintain tongue mobility

3. Restore mastication and speech

B. Reconstruction of large defects can either be immediate or be delayed. Ideally, one would plan immediate reconstruction under a single anesthetic. However, if there is a question as to surgical margin, or if the patient’s health demands it, a delay before reconstruction may be advisable.

C. Choice of reconstructive technique depends on the defect size and location.

1. Small bone defects, especially lateral ones, may be addressed with either no repair or with autologous bone graft. However, non-vascularized bone grafts tolerate radiation poorly.

2. Metallic implants (such as mandibular reconstruction bars) can serve as spacers to maintain position, but they often ultimately fail or lead to complications, including exposure and infection.

D. Vascularized bone flap is the method of choice most bony defect reconstruction, particularly anterior ones. Such flaps promote healing, resist resorption, and permit dental restoration with osseointegrated implants.

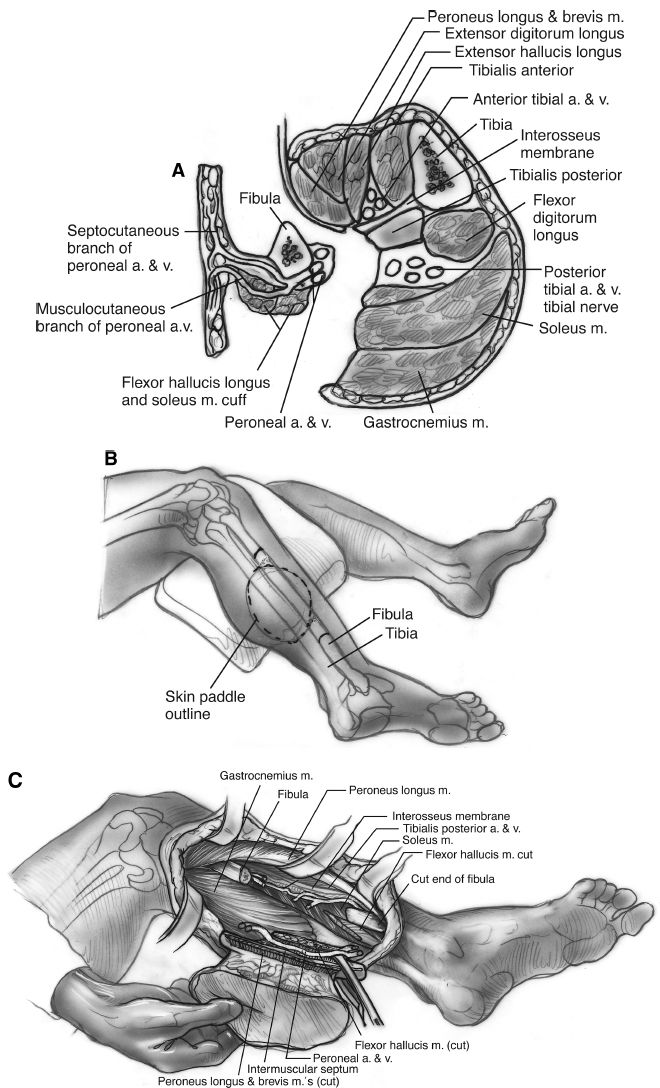

1. Free fibula flap (Fig. 18-1):

a. Segment of bone up to 40 cm long available, along with the overlying skin

b. Based on perforators from the peroneal artery (2 mm diameter, 6 to 10 mm length)

c. Causes minimal functional debility.

d. Leaves at least 6 to 10 cm of distal aspect of fibula to avoid destabilization of ankle.

e. Key landmarks: Head of fibula and lateral malleolus

f. Can leave small cuff of soleus and flexor hallicus longus muscles to avoid disruption of periosteum.

g. Important to identify and preserve common peroneal nerve at head of fibula and superficial peroneal between fibula and extensor digitorum longus.

h. Can make osteotomies in fibula to allow for curve of flap.

i. Often secured in place with large mandibular plate and screws. These can be pre-fabricated pre-operatively based on CT imaging. Screws should be unicoritcal and on opposite side of pedicle to avoid injury.

j. CT angiography or magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) is used preoperatively to assess the arterial anatomy. The leg opposite the defect is usually chosen to allow for optimal skin paddle and pedicle placement in the recipient neck.

h. Allows for osseo-integrated implants in the future.

2. Iliac crest bone flaps

a. Based on the deep circumflex iliac artery (1 to 3 mm diameter, 5 to 7 cm length), have a natural curve resembling the mandible.

b. Both iliac crests can be used to perform a total mandibular reconstruction.

c. Can provide 16 cm length and for mandible should use 2 cm height.

d. Can use one or two cortices though inner cortex usually sufficient for mandible and allows for decreased donor site morbidity.

e. Skin paddle marked over anterior iliac crease and can extend from ASIS to posterior axillary line.

Figure 18-1. Free fibula flap harvest, cross-sectional view. CT angiography or MRA is often used pre-operatively to assess the arterial anatomy. The leg opposite the defect is usually chosen to allow for optimal skin paddle and pedicle placement in the recipient neck.

a. Pedicle: Subscapular artery (3 to 4 mm diameter, 4 to 6 cm length)

b. Bone size up to 15 cm

c. Very large skin pedicle and quality bone

d. Requires position changes to access

4. Radius, rib, and metatarsal are other donor options for vascularized bone transfers for the mandible

IV. THE NECK

A. Goals

1. Protect vital neck structures, that is, the great vessels of the neck and the trachea

2. Prevent regional complications, which include chylous fistula, oropharyngocutaneous fistula, carotid artery blowout, and wound infection due to intraoral contamination

B. Pedicled pectoralis major flap: Useful for neck coverage

1. Origin: Medial clavicle, sternum, anterior ribs (second to sixth), external oblique, and rectus abdominis

2. Insertion: Upper humerus, 10 cm from humeral head on lateral side of intertubercular sulcus

3. Function: Adduction and medial rotation of arm

4. Maximal mobilization is achieved by dividing the insertion and clavicular attachments

5. Primary pedicle is the thoracoacromial artery off axillary artery

6. Secondary blood from internal mammary perforators, intercostal perforators, and lateral thoracic artery

7. Overlying skin may be transferred with the flap and should be positioned so minimal tension upon inset

8. Flap is dependable, but bulky

9. *Innervation: Medial and lateral pectoral nerves (named for origin in brachial plexus rather than region of pectoralis muscle innervated).

C. Pedicled latissimus dorsi flap

1. Thinner flap than the pectoralis, and the skin paddle is more likely hairless

2. Donor defect is favorable, and a paddle up to 10 cm can be harvested with primary closure of the skin.

3. Disadvantage: Intra-op positioning change when used for anterior neck wounds

4. Origin: Broad aponeurosis from thoracolumbar fascia and spine of lower sixth thoracic vertebrae, sacral vertebrae, supraspinal ligament, and posterior iliac crest.

5. Insertion: Intertubercular groove of humerus

6. Dominant pedicle: Thoracodorsal branch of the subscapular artery, the flap may be tunneled either below pectoralis major or subcutaneously along the anterior chest.

7. Secondary pedicles: Posterior intercostal perforators, lumbar artery perforators

8. Innervation: Thoracodorsal nerve (C6 to C8)

9. Common complication: Seroma formation at the donor site; drains are mandatory; and fascial quilting and/or fibrin are advocated by some to reduce seroma rate

D. Trapezius flap: Three different flaps can be raised:

1. *Superior trapezius flap: Based on the occipital artery and paravertebral perforators. It is the most reliable. Its skin paddle extends laterally across the top of the scapula.

2. *Inferior trapezius flap: Relies on the descending branch of the transverse cervical artery (also called dorsal scapular). It can be used either as a muscle or as a myocutaneous flap. Its point of rotation is posterior, at the base of the neck.

3. Lateral trapezius flap: Based on the superficial transverse cervical artery over the acromion. It can be useful for small lateral defects.

1. Supplied by first four perforators from the internal mammary artery.

2. A delay procedure will permit more lateral skin to be used safely.

3. Flap is thin and can reach the oral cavity.

4. Can raise up to a 10- × 20-cm fasciocutaneous flap.

5. Donor site often requires skin graft and less aesthetic closure.

V. THE ORAL CAVITY

A. Goals

1. Maintenance of oral competence.

2. Provision of support for the floor of the mouth.

3. Prevention of aspiration by maintaining or restoring sensation and mobility.

B. Tongue flaps: Can be used for closure of small intraoral defects, as long as care is taken not to tether the tongue.

C. Palatal or palatopharyngeal flaps: Can be used to fix small defects in the palate.

D. The free radial forearm flap

1. First choice for larger intraoral defects.

2. Based on the radial artery and venae comitantes and/or cephalic/basilic veins.

3. Ideal for intraoral lining due to flap thinness. It can be made sensate by attaching the lingual nerve to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

E. The pedicled latissimus dorsi flap: Can be used for extensive oral cavity defects

1. Advantage of large size, but the arc of rotation can limit its use in the oral cavity.

2. Alternatively, it can be used as a free flap.

3. *Based on thoracodorsal artery

F. The gastro-omental free flap: Provides a secreting mucosal surface useful in preventing post-radiation xerostomia.

VI. THE TONGUE

A. Goals: Maintenance/restoration of mobility, preserve speech, and swallowing function.

B. Reconstruction may not be necessary if the defect volume is low. The tongue heals exceptionally well; infection, scarring, and tissue loss are rare.

C. Partial glossectomy

1. Can be repaired with “setback” procedures, using the lateral anterior tongue to provide bulk and support to the tongue base.

2. Outcomes from these procedures can be excellent, provided that at least one hypoglossal nerve is maintained and oral cavity obliteration can be achieved with the remaining volume.

D. Hemiglossectomy or anterior 2/3 glossectomy: Radial forearm free flap: Pliable tissue can be designed in a “rectangle tongue template” to achieve oral cavity obliteration and premaxillary contact for oral intake.

E. Total glossectomy reconstruction requires larger volume. Primary goal to restore speech and swallowing function. Adequate bulk in the oral cavity will help food propulsion and can seal against the palate. Choices for reconstruction are:

1. Rectus abdominis free flap: The large volume flap permits creation of two or three separate cutaneous islands for complex reconstructions. A perforator-based rectus can help tailor the volume of free tissue transferred.

2. Latissmus dorsi: Can be used as either a free or a pedicled flap.

VII. THE HYPOPHARYNX

A. Hypopharyngeal and esophopharyngeal defects are either partial or circumferential (total).

B. For partial defects, options are

1. Primary closure

a. Care must be taken not to narrow the lumen excessively.

b. Width of mucosa must be at least 3 cm for primary closure (pharynx must permit passage of at least a 34 French catheter for swallowing)

2. Skin or dermal grafts: May be used for partial defects of the lining of esophagus or pharynx. They are initially secured with a stent to allow adherence and prevent stricture formation.

3. Pectoralis, latissimus, or trapezius muscles can be used to fill larger defects.

C. Circumferential reconstruction

1. Free jejunum: The historical flap of choice. A proximal segment is isolated on its mesentery and transferred to the neck, where it is placed in an isoperistaltic orientation. Endoscopic jejunum harvest is possible. Complications include a “wet” voice, halitosis, and dysphagia.

2. A tubed radial forearm flap: Particularly useful when jejunal harvest is not advisable. This reconstruction can be associated with a high incidence of stricture formation if adequate dimensions are not harvested.

3. Gastric transposition or gastro-omental flaps: For patients with tumors with significant inferior extension. Outside the scope of plastic surgery; typically performed by thoracic surgeons.

COMPLICATIONS

I. CHYLE LEAK

A. Dissection low in level iv places thoracic duct at risk

B. Presents with milky drain output when po intake starts

C. Usually noticeable within first 24-48 hours

D. *Treat with low/no fat diet or medium chain fatty acids and pressure dressing

E. If high output (>200 cc/8 hours)

1. Replace fluid loss and frequently check electrolytes.

2. Requires neck exploration to repair leak.

3. Octreotide can be used as adjunct in high output chyle leaks.

F. Fistula

1. Can occur at any site of repair or anastomosis involving oral cavity or pharynx.

2. Much higher incidence if previously radiated field.

3. Usually presents with doughy erythematous skin around pod 4 to 7 before frank salivary communication to skin.

4. Can be managed conservatively with continued npo, irrigations and local wound care; and if infected, culture-directed antibiotics.

5. If great vessels at risk, salivary diversion (bypass tube) and/or tissue coverage required.

6. Requires assessment of thyroid function and nutritional status to optimize healing.

7. Delayed fistula (months/years postoperatively) must raise suspicion for recurrence.

8. Carotid blowout must be in the differential dx of bleeding in any head & neck patient, especially if history of radiation.

G. Classified as a spectrum

1. Exposed carotid with impending bleeding.

2. Sentinel bleed – smaller volumes may herald a large volume bleed.

3. Acute rupture – high morbidity and up to 50% mortality.

4. Requires large bore iv access, secure airway, blood products.

5. Interventional radiology important as diagnostic and therapeutic adjunct.

6. In exposed carotid or sentinel bleed, can assess stroke risk with balloon occlusion for possible elective embolization or ligation.

7. Stents increasingly utilized but unknown duration of benefit.

8. Surgical ligation in cases of rupture but high risk of stroke.

PEARLS

1. Feeding via gastro-or jejunostomy tubes may be necessary for long-term management, particularly for patients who will require radiation therapy.

2. Feeding tubes should be placed at the time of reconstruction.

3. A reliable speech therapist is invaluable for rehabilitation of head and neck reconstruction patients.

QUESTIONS YOU WILL BE ASKED

1. How do you diagnose and treat a chyle leak?

Send drain fluid for triglycerides. Treat by changing tube feeds or PO diet to nonfat or medium-chain triglycerides. Apply pressure dressing to supraclavicular fossa. Octreotide may be used as an adjunct. If high output, you should consider fluid replacement of losses. If >200 cc/shift then consider returning to OR to identify/ligate the leak.

2. How do you treat a fistula after a jejunal free flap?

There are varying approaches to treat a fistula. The patient should be made/kept NPO and given nutrition via tube feeds. The wound should be kept clean, which can be done with irrigation. The patient’s thyroid function and nutrition should be optimized. The saliva should be diverted medially to protect the great vessels (a salivary bypass tube is sometimes used).

THINGS TO DRAW

Draw fibula osteoseptocutaneous flap in cross section, noting the muscles, septae, and vascular pedicles (refer to Fig. 18-1)

Recommended Readings

Chepeha DB, Teknos TN, Shargorodsky J, et al. Rectangle tongue template for reconstruction of the hemiglossectomy defect. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(9):993-998.

Cordeiro PG, Santamaria EA. Classification system and algorithm for reconstruction of maxillectomy and midfacial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2331-2346.

Disa JJ, Pusic AL, Hidalgo DA, et al. Microvascular reconstruction of the hypopharynx: defect classification, treatment algorithm, and functional outcome based on 165 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:652-663.

Haughey BH. Tongue reconstruction: concepts and practice. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1132-1141.

Haughey BH, Wilson E, Kluwe L, et al. Free flap reconstruction of the head and neck: analysis of 241 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:10.

Hidalgo DA, Pusic AL. Free flap mandibular reconstruction: a 10-year follow up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:438-449.

Makitie AA, Beasley NJ, Neligan PC, et al. Head and neck reconstruction with anterolateral thigh flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:547-555.

Theile DR, Robinson DW, Theile DE, et al. Free jejunal interposition reconstruction after pharyngolaryngectomy: 201 consecutive cases. Head Neck. 1995;17:83.

Urken ML, Weinberg H, Vickery C, et al. The neurofasciocutaneous radial forearm flap in head and neck reconstruction: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:161-173.

Zbar RI, Funk GF, McCulloch TM, et al. Pectoralis major myofascial flap: a valuable tool in contemporary head and neck reconstruction. Head Neck. 1997;19:412.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>