Key Words

bilateral cleft lip, premaxilla, prolabium, nasal deformity, anatomical spectrum

Synopsis

Repair of a bilateral cleft lip deformity is challenging yet rewarding. Many surgeons find it hard to achieve results comparable to those of unilateral repairs. Poorly planned surgeries can leave noticeable residual deformities. There is a combination of genetic and environmental factors that may affect development of cleft lip in weeks 4 to 10 of gestation. These patients present along a spectrum of severity. Wide clefts, and those with a prominent premaxilla, may benefit from pre-surgical molding. The child must be of appropriate weight, size, and vigor before undergoing surgery. The operation can be performed with a relatively basic plastic surgery instrument set. Arguably the important part of the operation is the surgical marking, which is done before making any incision. This will be the blueprint for the entire repair. After marking, local anesthetic is injected, and the procedure begins in a stepwise fashion as detailed later. Post-operative management is simple, and major complications are rare.

Clinical Problem

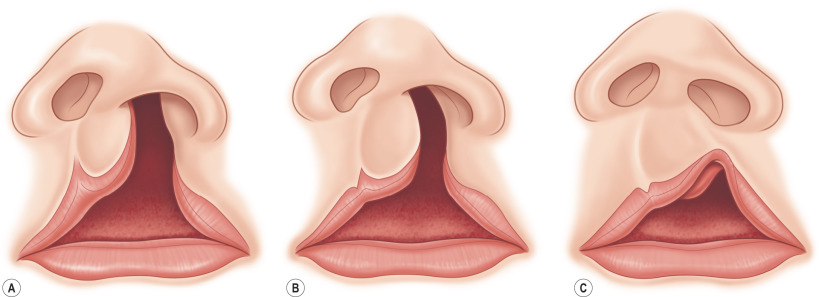

Repair of the bilateral cleft lip deformity requires an understanding of the aberrant anatomy involved. The pre-operative nasolabial anatomy is often very distorted, and closure can bring a tremendous sense of relief to the patient’s family. The surgical procedure, however, is nuanced and difficult; many surgeons feel that it is difficult to obtain results that compare favorably to those seen in unilateral repairs. A poorly designed and executed repair can leave residual deformities that are noticeable at conversational distance. It can also lead to significant restriction in maxillary growth. Older children or adult patients who have had an inadequately performed lip and/or palate repair often have significant maxillary retrusion. The primary goals of bilateral cleft lip repair are to achieve appropriate symmetry, address the nasal deformity, maintain continuity of the muscle, and design a philtrum/tubercle complex of appropriate size and shape. There are many techniques described in the literature; in this chapter we present one method that should allow a surgeon to achieve consistent and reliable outcomes.

Presentation

The associated cleft palate deformity is typically dictated by the severity of the lip deformity. Therefore patients with bilateral complete clefts of the lip will most often have a bilateral complete cleft of the secondary palate. In general, bilateral cleft lips represent about 10% of all cleft lip deformities.

Patients present with a wide range of anatomy, including the width of each cleft, the prominence/angle of the premaxilla, and the severity of the nasal deformity as well as the ability to maintain food intake. Although the diagnosis of a patient with a cleft deformity is straightforward, it is important to appreciate the spectrum of the process, because this will guide the surgeon’s ultimate repair.

Etiology

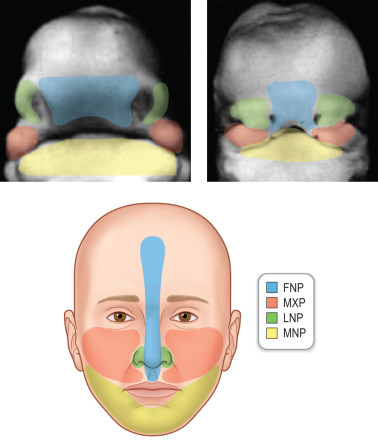

Cleft lips form as a result of failure of the medial nasal process to contact the maxillary process. Lip formation is set largely during weeks 4 to 7 of human development. Cleft palates typically develop from a failure of fusion of the opposing palatine processes of the paired maxillary prominences.

There is a genetic contribution to the development of cleft lip and palate that is only partially understood. It is likely that there are environmental factors that can contribute as well. No single gene has ever been identified as leading to cleft lip or cleft palate. It does appear that isolated cleft palate is a unique process that differs from cleft lip with or without a cleft palate. A positive family history of cleft does increase the risk in subsequent births. Possible environmental contributors include the use of phenytoin or other anti-convulsants, smoking during the first trimester, and poor folic acid supply in the perinatal period.

The incidence of cleft lip (of any form) in birth is roughly 1 : 1000 for Caucasian babies. This rate is slightly lower in African Americans and higher in Asian populations. Roughly 10% of cleft lip deformities are bilateral.

Associated Conditions

The vast majority of cleft lip patients do not have an associated condition or genetic disorder. Roughly 10% to 15% will have a syndrome along with the cleft deformity. The most common syndrome associated with cleft lip and palate is Van der Woude syndrome (which often presents with lower lip pits and hypodontia).

Pre-Operative Management

Physical Examination and Key Anatomy

In cleft lip, there is projection and sometimes malrotation of the premaxilla. The prolabium (the skin and mucosa over the premaxilla, centrally) does not have a Cupid’s bow, does not have a philtrum or philtral columns, and does not have any orbicularis muscle present. In incomplete cleft lips, there is the possibility of some muscle crossing the cleft. Orbicularis muscle fibers in the lateral lip insert onto the ala, which causes flaring of the alar base. Most bilateral cleft lip patients have a markedly shortened columella compared with those seen in unilateral cleft lip patients.

The physical examination by the surgeon will involve a thorough inspection of each of these structures. Evaluation of the premaxilla will be undertaken to assess the degree of protrusion and angulation. The palate will be assessed, as will the severity and details of the nasal deformity. The lip itself will be classified as symmetrical or asymmetrical as well as complete or incomplete. Important to note is the width of the clefts. Another important aspect of the physical examination involves assessing the overall patient to ensure that he or she is healthy and of an appropriate weight and size before any operation. Malnutrition or feeding difficulties can be picked up by an astute surgeon and should be addressed before any surgical intervention.

Pre-Operative Testing

There is no specific testing required before surgery, but adequate pre-operative management is essential. This typically involves making sure that the child has adequate nutritional intake and weight gain. Feeding can be difficult in patients with wide clefts of the lip and palate.

In modern cleft care, there is an increased awareness of the benefit of pre-surgical molding of the facial morphology. The goals of these types of interventions are to narrow the width of the cleft and to align alveolar segments. In bilateral cleft lips, the goal is also to help limit the projection of the premaxilla before closure. Certain devices are able to lengthen the columella as well. Many devices utilized currently are costly, require orthodontic specialists, and are unavailable in most developing countries. However, one of the most commonly used pre-surgical interventions remains the early and continuous taping of the lip in the first months of life, which can decrease cleft width by gradual tension.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree