Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses: Introduction

|

The pigmented purpuric eruptions are a group of dermatoses characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and, occasionally, telangiectasia in the absence of associated venous insufficiency or hematologic disorders (Table 168-1). Synonyms include persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis, purpura simplex, and purpura pigmentosa chronica. They are found most commonly on the lower extremities; however, the lesions may involve the upper body and rarely become generalized. There are reports of palm, sole, genital, and oral mucosal involvement. These benign, generally asymptomatic eruptions tend to be chronic, with remissions and flares. They share common histopathology features, including capillaritis, erythrocyte extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition.

Schamberg | Majocchi | Gougerot and Blum | Doucas and Kapetanakis | Itching Purpura | Lichen Aureus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Average age | 40s | 30s | 40s | 40s | 50s | 20s–30s |

Sex | M > F | F > M | M > F | F > M | M > F | M > F |

Onset | Insidious | Abrupt | Insidious | Abrupt | Abrupt | Abrupt |

Primary lesion | Red–brown macule | Annular purpuric, telangiectasia | Lichenoid papule | Red–brown macule + scale | Red–brown macule | Orange–brown papule or plaque |

Epidemiology

Pigmented purpuric eruptions are rare. There seems to be no ethnic or gender predisposition, and most patients are in their 30s and 40s (see Table 168-1), but children may be affected.

Pathogenesis

There are three different views of the pathogenesis of pigmented purpuric eruptions. The first is that they are due to a disturbance or weakness of the cutaneous blood vessels, leading to capillary fragility and erythrocyte extravasation. However, this does not account for the inflammatory infiltrate common to these disorders. The second proposed mechanism is humoral immunity. This suggested pathogenesis is supported by direct immunofluorescent studies showing vascular deposition of C3, C1q, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin A. However, several cases have not shown these deposits. The third proposed mechanism is cellular immunity.1,2 The infiltrate in pigmented purpuric dermatoses consists of lymphocytes, macrophages, and Langerhans cells. This inflammatory infiltrate leads to vascular fragility and subsequent leakage of erythrocytes. Aiba and Tagami used immunohistologic studies in eight cases of Schamberg disease to demonstrate that the dermal infiltrate was predominantly composed of helper–inducer T cells and OKT6-reactive cells,3 whereas the epidermis showed intercellular staining with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR antibody and OKT6 antibody. Based on this study, they concluded that a cellular immune reaction, specifically the Langerhans cell, likely plays an important role in the pathogenesis.

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses may be induced by drugs (Table 168-2),4–17 but other causes have also been implicated (Table 168-3).18–25 The mechanism behind drug-induced or other causes may be immune-mediated; however, this is unproven. There could be familial involvement, as was shown in a handful of cases, with one report consistent with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.26 Gravity and increased venous pressure may account for the lesions localizing to the lower extremities.

|

|

Types of Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses

Schamberg first described in 1901 a pigmented eruption on the legs of a 15-year-old boy that consisted of irregularly shaped reddish-brown patches with “pin head sized reddish puncta, closely resembling grains of cayenne pepper.”27

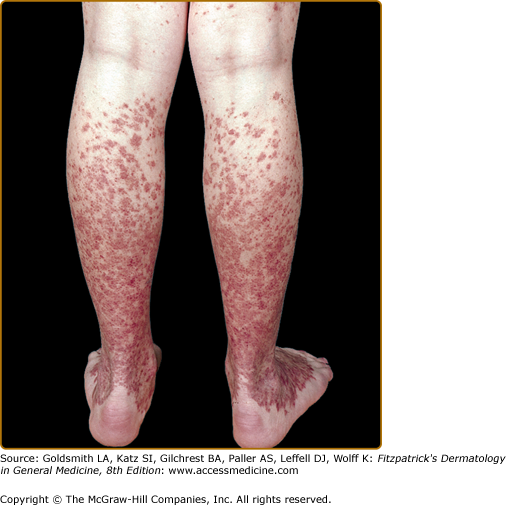

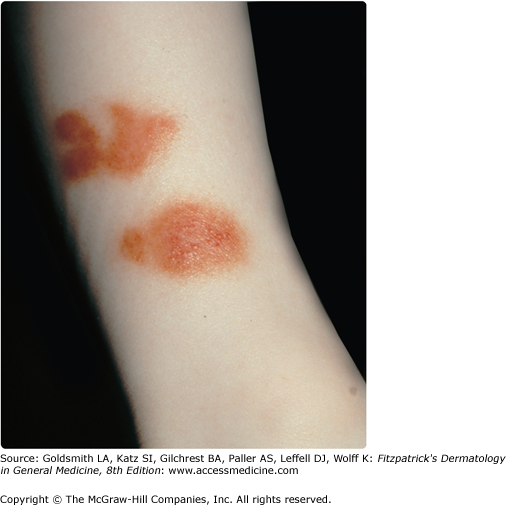

Although described in children and adolescents, the average age of onset of Schamberg disease is in the fifth decade.28 The lesions tend to develop insidiously on either or both lower legs. Lesions can involve the trunk or the upper extremities (Figs. 168-1 and 168-2). Schamberg disease is generally asymptomatic and persistent. Remissions and flares can occur indefinitely.

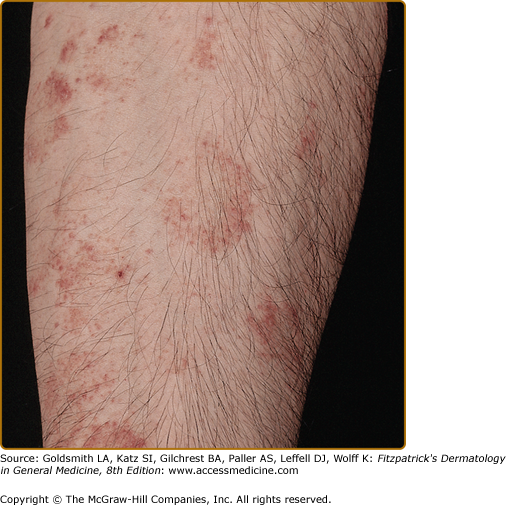

The original case of purpura annularis telangiectodes, described by Majocchi in 1896, was a 21-year-old man with annular patches of follicular and punctate reddish-brown macules, with telangiectasias and purpura on the lower extremities.29 The annular pattern is the distinctive characteristic of this subtype (Fig. 168-3). The individual lesions may have central hypopigmentation and slight atrophy, with peripheral telangiectasias. Linear and irregularly shaped patterns may also occur. The lesions most often present symmetrically on the lower extremities; however, the upper extremities and trunk may be involved. The lesions are asymptomatic and usually last several months with relapses and remissions. This subtype occurs more commonly in young adult females.

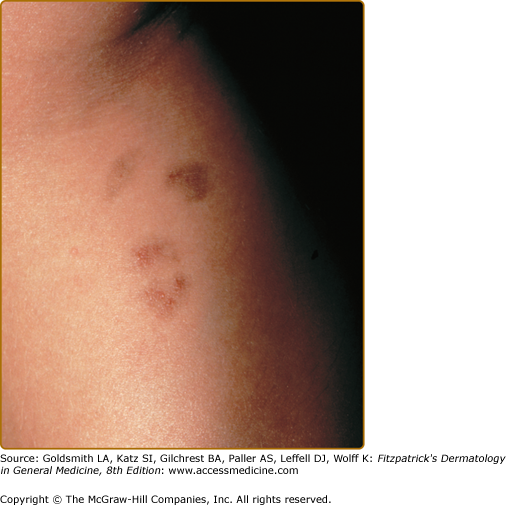

In 1925, Gougerot and Blum reported a pigmented eruption on the lower extremity of a 41-year-old man.30 The distinguishing feature of this subtype is the primary lesion, a reddish-brown polygonal or round lichenoid papule, in association with purpura or telangiectasia. Individual papules frequently coalesce into plaques with or without overlying scale. The term lichenoid describes the clinical appearance rather than a histologic feature. The color and morphology of the lesions can be mistaken clinically for Kaposi sarcoma (Fig. 168-4). Like the other subtypes, this eruption is found on the lower extremities and, occasionally, the arms. It occurs in males more often than females and has a chronic course.

Doucas and Kapetanakis reported a group of patients with an asymptomatic seasonal eruption occurring in the spring and summer.31 Its distinguishing quality is the mild scale overlying the typical patches and pinpoint erythematous macules. These spread rapidly over a period of 15–30 days, involving the legs and, occasionally, the upper body. This eruption fades without treatment over several months to years.

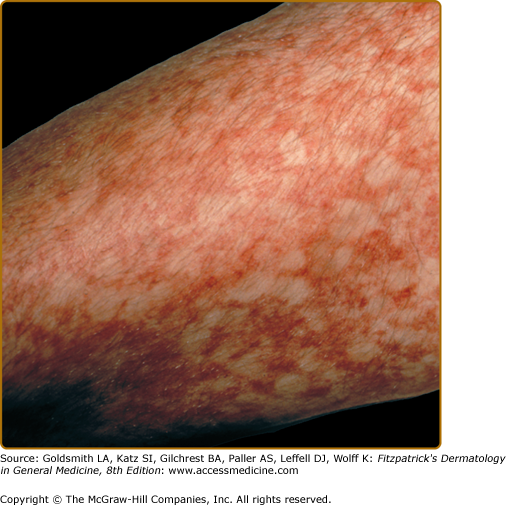

The acute onset and widespread involvement of orange–brown to purpuric macules with severe pruritus distinguishes itching purpura (Fig. 168-5).32,33 It usually appears first on the lower extremities and may become generalized. This disorder also has a chronic course, but there can be spontaneous remissions. Middle-aged men are most commonly affected.

Marten first coined the term “lichen purpuricus” in 1958,34 and Calnan later termed the same eruption “lichen aureus.”35 In this condition, lichen refers to the clinical and histopathologic descriptions. A dense, band-like, dermal, inflammatory infiltrate differentiates lichen aureus from the other pigmented purpuric dermatoses. Clinically, there are circumscribed areas of confluent gold to copper-orange to, less commonly, purple macules or papules (Fig. 168-6). Although these lesions may be intensely pruritic, they are typically asymptomatic. They are most commonly unilateral and localized on the lower extremities, but they can affect the forearms and trunk. This disorder has a predilection for young adults, with a peak incidence in the second and third decades. The lesions tend to be chronic, remaining stable or progressing slowly. Spontaneous resolution rarely occurs in adults, but in children the eruption may be self-limited.

Riordan et al reported a linear and pseudodermatomal distribution of pigmented purpura in four young men (average age, 22 years), which they called “unilateral linear capillaritis.”36 Both “segmental pigmented purpura” and “quadrantic capillaropathy” are considered variants of this linear pigmented purpura.37 The patients all had a macular, pigmented, unilateral eruption involving the foot, leg, or buttock. Clinically, the lesions most closely represented lichen aureus; however, the pathology did not show a lichenoid infiltrate. Furthermore, all four cases resolved spontaneously in approximately 2 years, unlike the typically chronic course of lichen aureus. Two more cases were reported in a young woman and man, both in their 20s and both with involvement of their arms. The lesion in the male was self-resolving, similar to previously reported cases, and the female’s lesion resolved with PUVA.39 There are also several reported cases of segmental or zosteriform lichen aureus and Schamberg disease. Two cases have been associated with trauma, and one case preceded the development of localized morphea.40–51