38 Pierre Robin sequence

Synopsis

Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) is not a syndrome.

Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) is not a syndrome.

PRS is a clinical triad consisting of glossoptosis, retrognathia, airway compromise, and possibly clefting of the secondary palate.

PRS is a clinical triad consisting of glossoptosis, retrognathia, airway compromise, and possibly clefting of the secondary palate.

PRS can be an isolated entity or found in the clinical setting of a syndromic child.

PRS can be an isolated entity or found in the clinical setting of a syndromic child.

The spectrum of symptoms is vast and an efficient multidisciplinary workup is necessary.

The spectrum of symptoms is vast and an efficient multidisciplinary workup is necessary.

This workup must begin with an evaluation of the airway.

This workup must begin with an evaluation of the airway.

The respiratory distress can be managed for many children with PRS and a base-of-tongue airway obstruction with prone positioning and supplemental oxygen.

The respiratory distress can be managed for many children with PRS and a base-of-tongue airway obstruction with prone positioning and supplemental oxygen.

If the respiratory distress is not corrected, then airway stenting may be of benefit.

If the respiratory distress is not corrected, then airway stenting may be of benefit.

If this measure fails then many surgical measures are described. There is controversy over which surgical route is best.

If this measure fails then many surgical measures are described. There is controversy over which surgical route is best.

Nutritional support is paramount if this patient population is to thrive. Depending on the patient, specialized bottles, nipples, feeding positions, and feeding tubes may be utilized.

Nutritional support is paramount if this patient population is to thrive. Depending on the patient, specialized bottles, nipples, feeding positions, and feeding tubes may be utilized.

This craniofacial patient must be followed chronically by many specialties as many systems may be involved.

This craniofacial patient must be followed chronically by many specialties as many systems may be involved.

Historical perspective

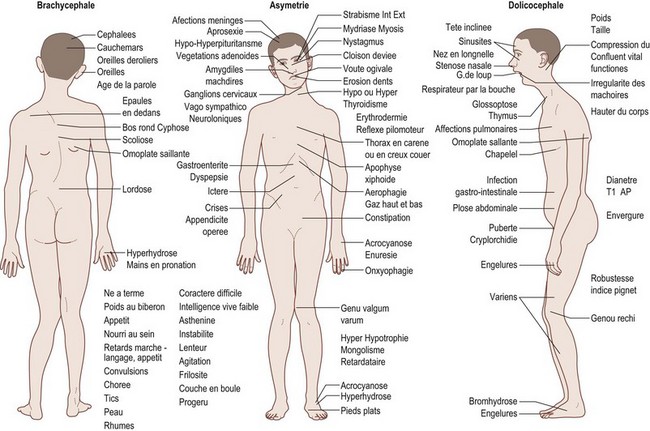

Despite earlier descriptions, the condition bears the name of the French stomatologist Dr. Pierre Robin. Dr. Robin lived from 1867 to 1949 and was a professor in the French School of Stomatology as well as editor of the periodical Stomatologie. His main contribution to the body of knowledge regarding PRS was the dissemination of it. Beginning in 1923 he wrote 17 articles on the problems of “glossoptosis” and is credited with introducing the term. He highlighted the severity of the potential respiratory complications and the difficulty these children have with feeding and weight gain. Robin felt that the more severe cases were quite dire and wrote, “I have never seen a child live more than 16–18 months who presented with hypoplasia such as the lower maxilla was pushed more than 1 cm behind the upper.” To combat the airway compromise Robin preferred a “monobloc” appliance to keep the mandible forward to restore the normal mandibulomaxillary relationship. Unfortunately, Robin drew many extraneous associations to this cohort and overestimated the incidence of the clinical entity at 3 out of 5 live births (Fig. 38.1).

In 1902, Shukowsky performed the first tongue lip adhesion (TLA) by simply suturing the tongue to the lip but the description was not published until 1911. This was successful in 1 patient, but another patient died of asphyxia when the suture pulled through the tongue. The use of TLA was not widely accepted during these initial descriptions. There followed a period of four decades when the treatments for respiratory distress in this cohort consisted of external traction devices placed on the mandible. One such device consisted of a pediatric back brace with a halo from which traction was applied. This was maintained for 4 weeks and was usually successful in alleviating the airway compromise. This modality, however, led to a significant amount of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Then, in the 1940s, Douglas published a refined technique of TLA and a resurgence in the technique occurred.1

PRS has evolved in name since the early descriptions as the understanding of the etiopathogenesis has advanced. Initially, the clinical constellation was termed “Pierre Robin syndrome.” In 1976 Gorlin, Pinborg, and Cohen created the term “Pierre Robin anomalad,” noting that this entity was not a syndrome.2 The term “anomalad” was used to describe an etiologically nonspecific complex that could occur with various syndromes of known or unknown origin or in isolation. Some authors began to use the phrase “Robin complex” but this was shortly replaced by “Pierre Robin sequence” (PRS) or “Robin sequence” by Pashayan and Lewis in 1984.3 Purists feel that eponyms should not include first names and prefer “Robin sequence.”

Basic science/disease process

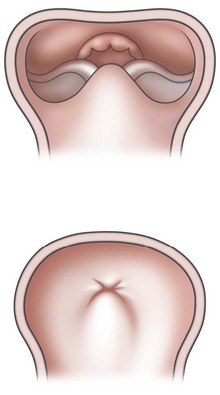

PRS is a clinical triad consisting of glossoptosis, retrognathia, airway obstruction, and possibly clefting of the secondary palate. The term “glossoptosis” refers to a posteriorly displaced tongue that obstructs the airway and does not refer to an enlarged tongue. The cleft palate is not obligatory for the diagnosis and can exist as either a U- or V-shaped cleft and is present in approximately 50% of cases (Fig. 38.2). PRS can be an isolated entity or found in the clinical setting of a syndromic child.

Estimates of mortality have improved as both the understanding of and treatment options for PRS have evolved. As stated above, Robin painted a bleak picture for any child with PRS. In 1946 Douglas reported greater than 50% mortality with conservative treatment.1 The major cause of mortality was felt to be secondary to aspiration. Current ranges of mortality for patients with PRS are between 2.1% and 30%. In 1994, Caouette-Laberge et al.4 stratified mortality after subclassification into three groups. For those with adequate respiration in prone positioning and the ability to be bottle-fed, the mortality was found to be 1.8%. For those with adequate respiration in prone positioning but the requirement of gavage feeds, the mortality was 10%. For those with respiratory distress necessitating endotracheal intubation and gavage feeds the mortality was 41%.

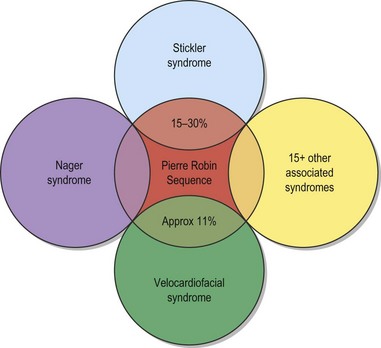

The etiology of PRS is still unclear. As the clinical entity is considered a sequence, there can be many postulated causes. Before any etiological considerations, a clear understanding of the difference between a syndrome and clinical sequence is important. A syndrome refers to a group of signs and symptoms that vary in degree of expression but ultimately result from a single pathological insult. A sequence describes a spectrum of anomalies that may be instigated by varying disease processes but ultimately converge in the same phenotypic findings. This differentiation is germane as a cohort of patients with PRS will be syndromic, like those with Stickler syndrome. The converse does not hold true as not all patients with Stickler syndrome have the phenotypic findings of PRS (Fig. 38.3). Approximately 80% of patients with PRS are nonsyndromic.

Shprintzen5 hypothesized that the etiology is multifactorial. The mandible may be programmed to be retrognathic if the child has an associated syndrome such as Treacher–Collins, Nager, or Stickler syndrome. This was termed a “malformational” cause. The retrognathic mandible can be from a “deformational” cause such as intrauterine growth constriction. The growth constriction can be caused by a multigravid pregnancy, oligohydramnios, or a uterine anomaly. This could place the child’s chin in a flexed position into the chest and restrict growth.

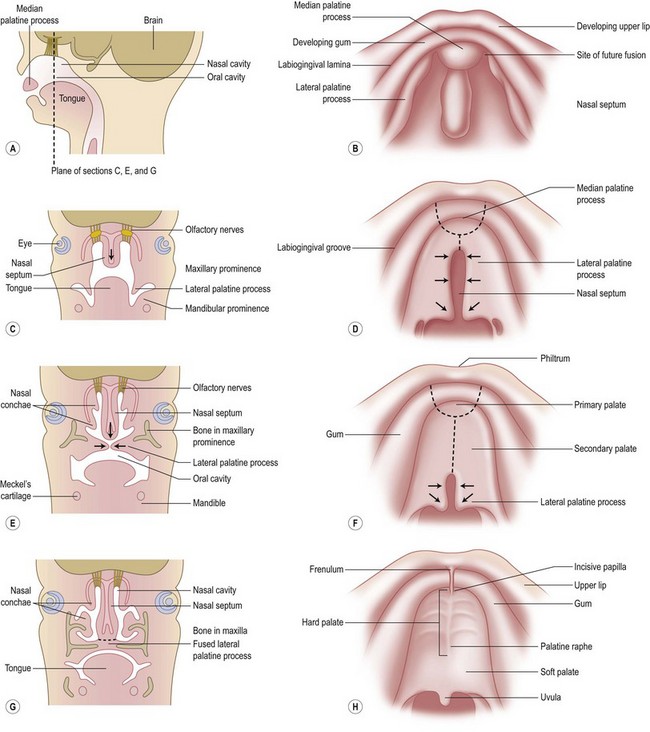

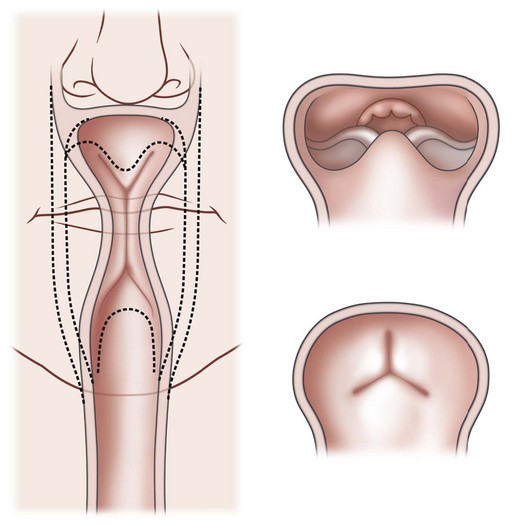

Chiriac and colleagues6 postulated three theories regarding the etiology of PRS. In the “mechanical theory,” the inciting event is mandibular hypoplasia that occurs in the 7th to 11th week of gestational life from various etiologies. The effect is a tongue that rides high in the oral cavity and interferes with the movement of the lateral palatine processes as they progress from a vertical to horizontal orientation (Fig. 38.4). Experimental animal models have mimicked this theory by inducing intrauterine constriction, inducing the triad of findings consistent with PRS. Some feel these events lead to a U-shaped palatal cleft in PRS due to the blockage by the tongue; however others feel that the cleft can be either U- or V-shaped. In the “neurological maturation theory,” a neuromuscular delay occurs in the musculature to the tongue, pharyngeal pillars, and palate. The delay has been noted on electromyogram to the respective sites of these patients. In the “rhombencephalic dysneuralation theory,” motor and regulatory organization of the rhombencephalus is related to a major complication in development.

Cohen7 also described several distinct mechanisms of etiopathogenesis: malformation, deformation, and connective tissue dysplasia. The final mechanism demonstrates a link between diseases of “connective tissue dysplasia” and PRS. An example of this is PRS and Stickler syndrome. Many authors agree upon the influence of intrauterine exposure to teratogens in the formation of PRS. Possible teratogens include alcohol, trimethadione, and hydantoin.

Due to the multiple syndromes associated with PRS and the still unknown etiopathogenesis, analysis of inheritance can be difficult. Cohen in 19788 reported up to 18 associated syndromes with PRS. This list includes: Stickler syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, Moebius syndrome, del6q, Marshall syndrome, Treacher–Collins syndrome, Catel–Mancke syndrome, Kabuki syndrome, Nager syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, Weissenbacher–Zweymuller syndrome, popliteal pterygium, CHARGE association, Andersen–Tawil syndrome, collagen XI gene sequence, and achondrogenesis type II. The list of recognized associations can be quite extensive (Table 38.1).

Table 38.1 There are many recognized syndromes associated with Pierre Robin sequence. The postulated genetic locus is shown for several syndromes

Review of the literature of PRS demonstrates relevance in loci 2q24.1-33.3, 4q32-qter, 17q21-24.3, SOX9 gene on 17q24.3-q25.1, GAD67 on 2q31, PVRL1 on 11q23-q24, KCNJ2 mRNA, TCOF1, GAD67, COL2A1, COL9A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2.9 The roles of these genes are still not fully understood. They can have a causative role, make the condition more likely, be significant in the associated syndrome, or be coincidental to another process.

In a study of 47 children with isolated Robin sequence, Carrol et al.10 reported 9 cases with a positive family history and with a distribution of familial cases compatible with autosomal-dominant inheritance of reduced penetrance and variable expressivity. It is unclear, however, if many of the investigations were careful to exclude those with syndromic PRS. This is especially true in those cases of PRS associated with Stickler syndrome that may not manifest ocular and skeletal anomalies until later in childhood. In another study assessing children with isolated PRS, there was a family history of cleft lip or cleft lip and palate in 27.7%. No relatives had a history of PRS; however it is a possibility that the manifestations were present, not acknowledged at a young age, and outgrown in time in the family members.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

The respiratory disturbances are just as varied and may be profound at birth, requiring emergent intubation, or mild, and only noted during perturbing settings. In severe cases, periodic desaturations may occur, retractions may be visible, stridor may be audible, or hypoxia and hypoxemic neurological injury can result. These children can progress to develop cor pulmonale. By definition, the child with PRS must have an obstruction localized to the level of the base of the tongue. Additional levels of airway involvement can exist, and 10–15% of infants with PRS have been found to have laryngomalacia. The overall incidence of tracheomalacia in the general population is difficult to determine. Data from the Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam suggest an incidence of 1 in 2100 newborns.11

Infants with PRS may also have cardiac anomalies. Congenital heart defects are associated with PRS in 14% of cases.12,13 As mentioned previously, those with syndromic PRS may have cardiac findings specific to the named syndrome, as in velocardiofacial syndrome, persistent left superior vena cava syndrome, and Andersen–Tawil syndrome.

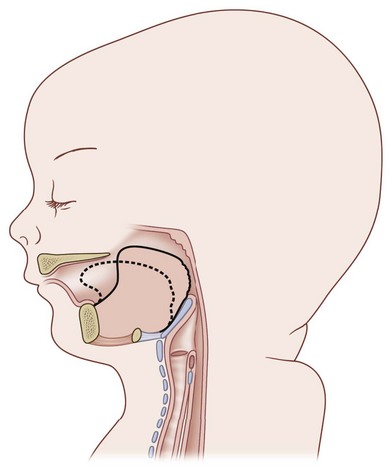

Patient selection

The first interaction with the patient may occur in the delivery suite. As respiratory distress may be lethal, the airway is of paramount importance. For the child suspected of having PRS, resuscitation according to the American Academy of Pediatrics Neonatal Resuscitation Program begins with prone positioning and supplemental oxygen. If this fails then a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or nasopharyngeal airway can be attempted (Fig. 38.5). If this modality fails, then endotracheal intubation may be necessary and can be aided with a fiberoptic laryngoscope. Due to the retrognathic mandible and glossoptosis, there have been many descriptions of specialized ways to insert the endotracheal tube, but these are in the controlled environment of an operating room. All the prior steps are contingent on the neonate’s cardiopulmonary status, the skill of the physician managing the airway, and the availability of proper equipment. If all else fails in the acute setting, an emergent tracheotomy may be warranted. If a child is diagnosed with multiple congenital anomalies prenatally, an EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) procedure may be a viable option. In this scenario, the airway can be secured while the child is still receiving placental circulation.

Fig. 38.5 A lateral radiograph demonstrating a nasopharyngeal tube bypassing the base-of-tongue obstruction.

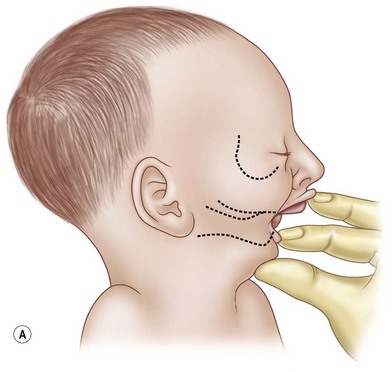

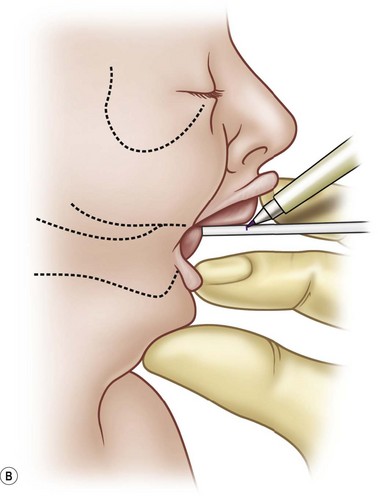

The pathognomonic mandible must be assessed. A metric is needed for growth and progress of the diminutive mandible. This can be simply obtained by using a wooden end of a cotton-tipped applicator to measure the maxillary–mandibular discrepancy (MMD).14,15 The stick is pressed against the anterior aspect of the gingiva of the mandibular alveolus and a mark is made at the anterior aspect of the maxillary alveolus (Fig. 38.6). This value can be variable if not done systematically. As the mandible has a tendency to fall posteriorly in the supine position, the MMD should be obtained with the child upright. The MMD should not act as an absolute for selecting a treatment modality for the child with PRS. Some authors have stated that an MMD of 8–10 mm is an indication for surgical treatment. Robin himself16 stated that no infant lived past 18 months of age when the MMD was greater than 10 mm. Surgical indications should arise from the overall clinical picture and endoscopic assessment.

The respiratory assessment is paramount in selecting the proper treatment when PRS is clinically suspected. For the clinical entity to exist there must be a respiratory obstruction, and the clinician must evaluate for desaturations. These desaturations can happen at any time, from birth to the point at which the native growth of the mandible helps the base of the tongue clear the airway or the oropharyngeal musculature gains the control required to keep the airway patent. Some feel that the obstructive events in newborns with PRS increase in frequency in the initial 4 weeks of life. Therefore, a false sense of security should not occur after a brief evaluation. In a series by Gosain and Nacamuli,17 18 patients presented in the first week of life and 3 patients presented between 12 and 33 months of age. The respiratory assessment should include continuous pulse oximetry in different scenarios, such as when the child is awake, sleeping, and feeding. The monitoring time required for the sleeping group should be a minimum of 12 hours for neonates and a regular period of sleep for children. The criteria for desaturations are defined as having any single oxygen saturation value less than 80% at any time or if oxygen saturation values are less than 90% for 5% or more of the monitored time. Based on this assessment, the children are placed into two groups: those with desaturations and those without. If a child is found to have no desaturations during sleep but is clinically still suspicious, a formal sleep study is obtained. If the sleep study is positive then the child is placed in the positive desaturation group. For those without desaturations, a screening for feeding difficulties is undertaken.

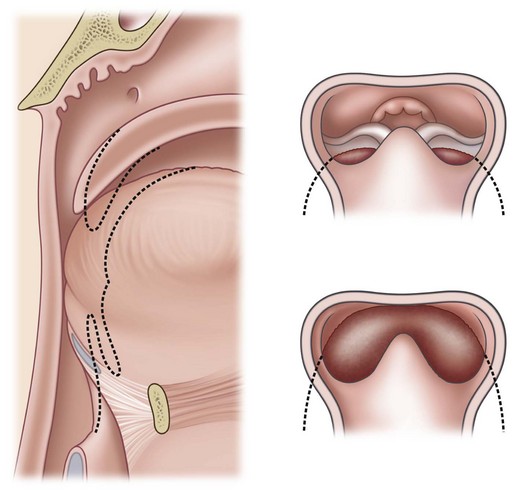

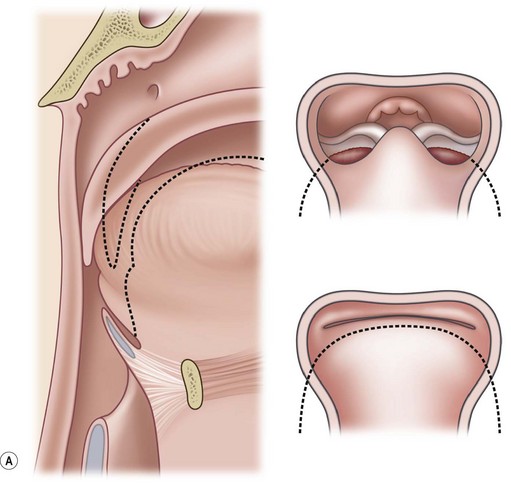

Sher and colleagues18 described four types of obstruction seen via flexible nasopharyngoscopy in 53 children with PRS. Type 1 is described as “true glossoptosis,” and consists of a tongue that contacts the posterior pharynx at a level below the soft palate (Fig. 38.7). Type 2 consists of a tongue that is displaced posteriorly as in type 1 but at the level of or above the soft palate, such that the palate becomes sandwiched between the tongue and posterior pharyngeal wall in the upper oropharynx (Fig. 38.8). Type 3 consists of an obstruction caused by a medial collapse of the lateral pharyngeal walls (Fig. 38.9). Type 4 consists of the pharynx collapsing or constricting as a sphincter (Fig. 38.10). In the analysis by Sher et al.,18 59% were classified as type 1, 21% were type 2, 10% were type 3, and 10% were type 4. As stated earlier, 10–15% will also present with laryngomalacia, and the clinician must recognize this. Occasionally the craniofacial surgeon will be consulted after intubation or tracheostomy. These patients will still require endoscopic evaluation.

Treatment

To begin a discussion of the treatment of the airway obstruction, the underlying mechanism must be understood. Robin19 described the mechanism as a tongue that is displaced posteriorly due to the retrognathic mandible. Others have similarly described the tongue base acting as a “ball valve” draping over the glottis (Fig. 38.11). The muscular coordination of the oropharynx also plays a role in the obstruction, highlighting the multifactorial mechanism of obstruction in PRS. The neuromuscular impairment may predispose the airway to collapse. Inadequate functioning of the genioglossus was described by Delorme et al.20 In this description, the genioglossus is shortened and rotates the tongue posteriorly. Delorme and colleagues went on to postulate that this causes the retropositioned mandible, and not the converse. This theory is not widely accepted and demonstrates the complexity and lack of consensus of the possible etiology.

Another point of contention is the role that a cleft palate plays in degree of symptoms in PRS. Some feel that this anatomic finding will exacerbate the upper airway obstruction. Hotz and Gnoinski21 theorized that the tongue may become impacted in the palatal cleft, perpetuating the posterior positioning of the tongue and upper airway obstruction. Others assert that the cleft may be beneficial and act as an oronasal passage for air.

Nonsurgical airway management

The algorithm for the acute management of the airway in this cohort was described earlier. Cardiopulmonary monitoring is an absolute during this critical time. If desaturations are present in a child with a diminutive mandible, prone positioning should be attempted. The benefit of this maneuver was described by Robin in 193422 and radiographically confirmed by Sjolin in 1950.23 This acts to displace the chin and tongue base forward. Cogswell and Easton24 showed that the least resistance to airflow for children with PRS is in the prone position. This maneuver can be bolstered by providing the child with supplemental oxygen. If effective, the prone position must be maintained 24 hours a day, even during feeding, baths, and diaper changes (Fig. 38.12).

If prone positioning fails, then a 3-mm nasopharyngeal airway should be placed. Some authors recommend placement to a depth of 8 cm or until the resolution of the obstruction occurs. A recent series demonstrated excellent success in 20 neonates with PRS managed with prone positioning and placement of a nasopharyngeal airway.25,26 In this report, the nasopharyngeal stent remained indwelling for an average of 44 days and the children remained in hospital during this time. In another report, the median hospital stay was 10 days with the aid of home healthcare services. In this series the average time to removal of the nasopharyngeal airway was 105 days. With proper training, the parents can care for the nasopharyngeal airway without the assistance of a home nurse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree