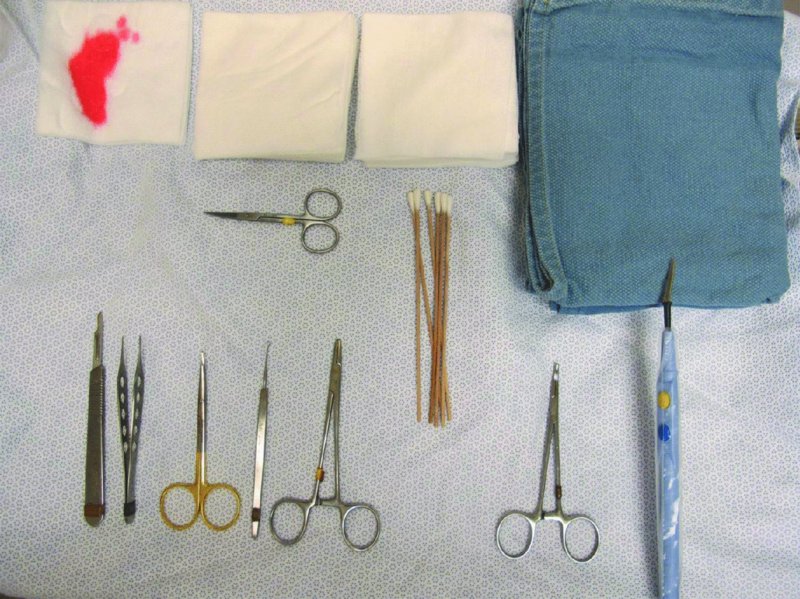

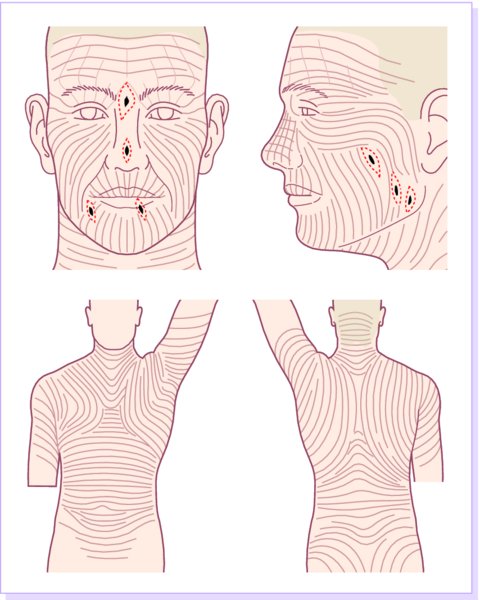

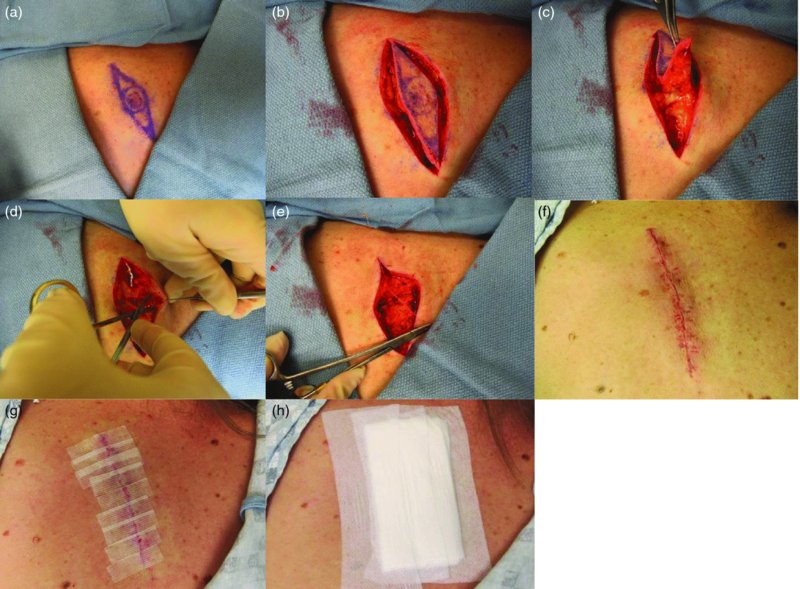

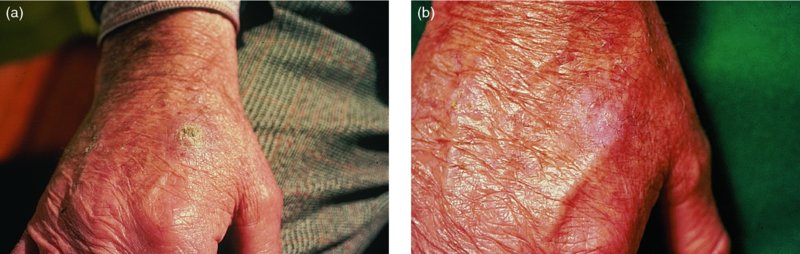

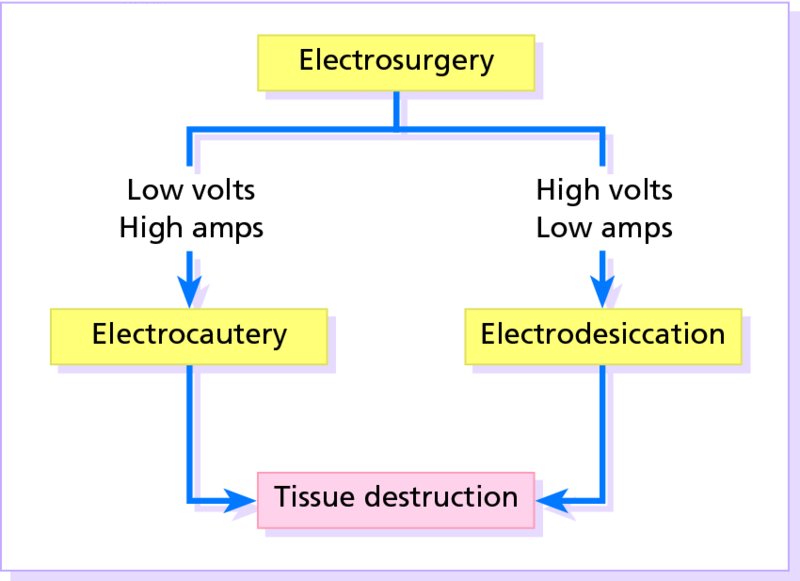

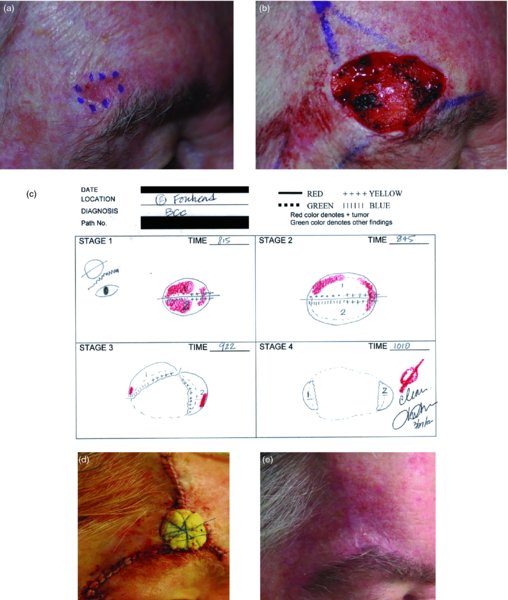

27 The skin can be treated in many ways, including surgery, freezing, burning, ultraviolet radiation and lasers. Some broad principles are discussed here. As our population ages, and becomes more concerned about appearances, requests for skin surgery are becoming more common. The distinction between traditional dermatological surgery and cosmetic surgery is blurring. There are few over the age of 50 years who do not have a benign tumour (see Chapter 20) that they consider unsightly and wish to have removed. There are also many who are unhappy with a skin damaged by cumulative sun exposure (p. 265), or concerned about medically trivial abnormalities on their face. To term the treatment of all these as ‘cosmetic’ seems harsh. Health care systems cannot cover the cost of treating all such problems, but family doctors and dermatologists should be able to discuss with their patients any recent developments in phototherapy, laser treatment and specialized surgery that might help them. For example, doctors should be able to explain that diode lasers can remove unwanted hair permamently without visible scarring, and the pros and cons of such treatment, as well as supplying the names of specialists. No surgery is minor. Always mark the site prior to the procedure to reduce error. Use an aseptic technique, if possible in a designated room with appropriate facilities. There are few exceptions but these include bedside biopsies on unconscious patients and those too ill to move. Most biopsies can be performed with clean gloves and isopropyl alcohol prep to the skin (Figure 27.1). Excisions and Mohs’ reconstruction should be performed with additional antiseptic prep (chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine solution) and sterile gloves (Figure 27.2). Pre-packed sterile packs of instruments and swabs have made these procedures much easier. Local anaesthesia is usually adequate for skin biopsies, excisions, Mohs’ surgery and reconstruction. Most dermatologists use 1 or 2% lidocaine. The addition of adrenaline (epinephrine) constricts local blood vessels to prolong the anaesthetic effect and reduce bleeding (Formulary 2, p. 425). Figure 27.1 An example of a biopsy tray setup with clean gloves. Figure 27.2 Typical excision tray. Hibiclens is positioned at the top left corner (for prepping the skin), followed by sterile gauze and sterile towel (for draping the surgical area). Surgical instruments include forceps, blade and blade holder, suture scissors and undermining scissors, skin hook, needle driver, haemostat and electrocautery. Antibiotic prophylaxis is effective in reducing bacteraemia during major surgery, but it probably does not prevent endocarditis or haematogenous total joint infection after simple skin surgery. Routine dermatological surgery (including biopsies, curettage and simple excisions) performed on clean intact skin carry a very low risk of wound infection (1–4%). Because of the low risk of bacteraemia in the setting of skin surgery, British guidelines (see Further reading) suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis for endocarditis is not recommended for routine dermatological surgery even in the presence of a pre-existing heart lesion (e.g. prosthetic valves, history of bacterial endocarditis, congenital cardiac malformation, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valvular dysfunction and mitral valve prolapse with regurgitation). Similarly, routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary even in patients at high risk (those within the first 2 years of a joint replacement). However, in locations where the risk of wound infection increases to 5–15%, such as eroded or ulcerated skin, respiratory or buccal mucosa, groin and lower leg, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of bacterial endocarditis or joint infection. The risk of contracting a blood-borne virus infection from a patient by a needle stick or scalpel injury during a surgical procedure is low in the United Kingdom. It varies with the individual virus; it is higher with hepatitis B (HBV) (5–40%) than with hepatitis C (HCV) (3–10%) and HIV (0.2–0.5%). The highest risk of acquiring HIV is following percutaneous injury involving a hollow needle that has been in the vein or artery of an HIV positive patient with a high viral load. The risk of acquiring HIV through mucous membrane exposure is less than 1 in 1000 and there is no evidence of risk from blood in contact with intact skin. These days, any patient can carry an undiagnosed infection, so gloves should be used for all surgical and other procedures where there is risk of contacting blood or body secretions. When operating on a high risk patient the surgeon should wear not only gloves, but also a water-repellent gown, protective headwear, a mask with visor and protective footwear. Other good preventative measures include: Immunization is currently only effective against HBV infection. All medical staff who come into contact with blood or blood-related products should be immunized against this virus. Immediate action after a needle and/or scalpel injury. Further information can be found in the British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines (see Further reading). The indications for biopsy, and the techniques employed, are described in Chapter 3. Briefly, shave or punch techniques can be used to obtain a sample specimen for histopathological examination. Excision under local anaesthetic, using an aseptic technique, is a common way of removing small tumours for histopathologic examinatation and surgical cure. First, the lesion must be examined carefully and important underlying structures (e.g. the temporal artery) noted. If possible, the incision should run along the line of a skin crease, especially on the face. If necessary, charts or pictures of standard skin creases should be consulted (Figure 27.3). After injection of the local anaesthetic the lesion is excised as an ellipse with a margin of normal skin, the width of which varies with the nature of the lesion and the site (Figure 27.4). Benign lesions can be removed with 1–2 mm margins. Recommended margins for basal cell (BCC) and squamous cell carcionomas (SCC) is usually 4–5 mm and for atypical naevi is 3–4 mm. The length of the fusiform shape should be about 3–4 times the width to minimize redundant cones of tissue or ‘dog-ears’ at the tips. The scalpel should be held perpendicular to the skin surface and the incision should reach the subcutaneous fat. The ellipse of skin is carefully removed with the help of a skin hook or fine-toothed forceps. Larger wounds, and those where the scar is likely to stretch (e.g. on the back), are undermined carefully to mobilize the tissue and reduce wound tension. It is then closed in a layered fashion – the subcutis and dermis is closed with absorbable sutures (e.g. Dexon) before apposing the skin edges without tension using non-absorbable interrupted or running sutures such as nylon or Prolene (see Further reading for precise techniques of suturing). Stitches are usually removed from the face in 5–7 days and from the trunk and limbs in 10–14 days. Artificial sutures (e.g. Steri-Strip) may be used to take the tension off the wound edges after the stitches have been taken out (Figure 27.5). Figure 27.3 Skin wrinkle figures are helpful in deciding the direction of wounds following skin surgery. Those performing dermatological surgery should have ready access to them. Figure 27.4 Suspicious pigmented lesions should be removed with a 2-mm margin marked out in advance. Figure 27.5 Steps for surgical excision of a melanoma in situ. (a) An fusiform shape is marked with 5-mm margins. (b) Incision is carried perpendicular to the skin down to the subcutaneous fat. (c) The tissue specimen is carefully removed with the help of a fine-toothed forceps. (d) Undermining is carried out with a skin hook to minimize trauma to the epidermis. (e) The dermis is closed with absorbable sutures. (f) The epidermis is reapproximated with subcuticular sutures. (g) Steristrips are placed. (h) Pressure dressing is left in place for 24–48 hours. Many small lesions are removed by shaving them off at their bases with a scalpel tangential to the skin surface under local anaesthesia. This procedure is suitable only for exophytic tumours that are believed to be benign. Some cells at the base may be left and these, in the case of malignant tumours, could lead to recurrence. This modified shave excision extends into the subcutaneous fat. Instead of tangentially shaving off the growth, it is ‘scooped’ out, leaving a crater-like wound. The technique is used to remove certain small skin cancers and worrying melanocytic naevi. It tends to leave a more noticeable depressed white scar when compared with a shave excision but the technique provides tissue that allows the dermatopathologist to determine if a tumour is invading and to measure tumour thickness if the lesion is a melanoma. Furthermore, the technique may ensure complete removal more adequately than shave excision. Freezing damages cells by intracellular ice formation. The ensuing thaw compounds this damage by osmotic changes across cell walls and by vascular stasis. The damage is semi-selective in that cellular components are more susceptible to cold injury than stromal ones. There is also some variation in susceptibility between different cells, for example melanocytes are more vulnerable to cold injury than keratinocytes. Cryotherapy is a most convenient procedure for use in general outpatient and domiciliary practice. Further advantages include its cost effectiveness, its speed and suitability for those who fear surgery, and its lessened chance of transmitting blood-borne infections. These have to be weighed up against its two main disadvantages: short term pain and no histological confirmation of the lesion being treated. Several freezing agents are available. Liquid nitrogen (–196°C) is the most popular and is now used more than carbon dioxide snow (‘dry ice’, –79°C). It is effective and used often for viral warts, seborrhoeic keratoses, actinic cheilitis, actinic keratoses, simple lentigos and some superficial skin tumours (e.g. intraepidermal carcinoma and lentigo maligna). It is applied either on a cotton bud or with a special spray gun (Figure 27.6). The lesion is frozen until it turns white, with a 1–2 mm halo of freezing around. Two freeze–thaw cycles kill tissue more effectively than one but are usually unnecessary for warts and some keratoses (Figure 27.7). Treatment of BCC with liquid nitrogen cryosurgery requires significantly longer freezing time to reach tissue temperatures of –50 to –60°C. Patients should be warned to expect pain and possible blistering after treatment. Care should be taken when treating warts on fingers as digital nerve damage can follow over-enthusiastic freezing. Standard freeze–thaw times have been established for superficial tumours (see Further reading) but temperature probes in and around deep tumours are needed to gauge the degree of freezing for their effective treatment. A crust, including the necrotic tumour, should slough off after about 2 weeks. As melanocytes are very sensitive to cold injury, hypopigmentation at a treated site is common and may be permanent. Figure 27.6 Liquid nitrogen can be applied through a spray, or with a cotton wool bud direct from a vacuum flask (centre). Figure 27.7 Two freeze–thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen cleared this actinic keratosis. (Dr R. Dawber, The Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK. Reproduced with permission of Dr R. Dawber.) Curettage under local anaesthetic is also used to treat benign exophytic lesions (e.g. seborrhoeic keratoses; Figure 27.8) and, combined with electrodesiccation (p. 371), to treat some BCC. Its main advantage over purely destructive treatment such as laser or liquid nitrogen is that histological examination can be carried out on the curettings. As morphology of the tumour is fragmented, the curetting technique does not allow for histological confirmation of tumour clearance and should not be used if there is uncertainty about the primary diagnosis. A sharp curette is used to scrape off the lesion and haemostasis is achieved by local haematinics, by electrocautery or electrodesiccation. The wound heals by secondary intention over 2–3 weeks, with good cosmetic results in most cases. Figure 27.8 Curettage beats excision if a seborrhoeic wart has to be removed. Stretching the skin helps to hold the lesion steady. When a BCC is treated, the curette is scraped firmly and thoroughly along the sides and bottom of the tumour (the surrounding dermis is tougher and more resistant to curettage than the carcinoma) and the bleeding wound bed is then electrodesiccated aggressively. This stops bleeding and destroys a zone of tissue under and around the excised tumour to provide a tumour-free margin. The process is repeated once or twice at the same session to ensure that all of the tumour has been removed or destroyed. Only small BCC outside the skin folds should be treated in this way. The recurrence rates are relatively high for tumours in the nasolabial folds, over the inner canthi and on the nose, glabella and lips. The technique should not ordinarily be used for infiltrative or sclerosing BCC, invasive lesions larger than 1–2 cm, rapidly growing tumours or for those with micronodular features on histology. This is often combined with curettage, under local anaesthesia, to treat skin tumours. The main types are shown in Figure 27.9. Figure 27.9 Types of electrosurgery. This form of surgery for malignant skin tumours is time-consuming and expensive, but allows for greater tissue conservation and the highest cure rate compared with excision or curettage. Mohs’ surgery was pioneered by Dr Frederic E. Mohs in the 1950s. In the United Kingdom, the Mohs surgeon is normally a consultant dermatologist who has undertaken additional fellowship training in Mohs’ micrographic surgery, dermatopathology of skin tumours and reconstruction. A surgeon using Mohs’ technique functions as both the surgeon and the pathologist, which allows for precise mapping and margin control. First, the tumour is removed with a narrow margin, usually 1–2 mm instead of the usual 4–6 mm required with standard excision. The excised specimen is then marked at the edges, mapped and rapidly frozen for histological processing in horizontal sections. This allows for microscopic examination of 100% of the tissue margin. In contrast, conventional histologic sections requires formalin fixation and takes several days to process. The cross-sectional slices of representative tissue or ‘bread loaf’ in conventional sections also examines less than 1% of the true margins. In most cases, each stage of Mohs’ surgery requires less than 1 hour to process and the entire procedure is performed under local anaesthetic. If the tumour extends to any margin, further tissue is removed from the appropriate place, based on the markings and mappings, and again checked histologically. This process is repeated until clearance has been proved histologically at all margins. The resulting wound can then be closed directly, reconstructed with a flap, covered with a split skin graft or allowed to heal by secondary intention. In general, Mohs’ surgery is useful to treat skin cancers at high risk of recurrence (Figure 27.10). There are many factors that have an effect on recurrence rate including histological features, location and patient features (Table 27.1). Low risk lesions can be treated with a number of surgical modalities mentioned in this chapter including excisional surgery and electrodessication and currettage (Table 27.2). In addition, patients who cannot undergo surgical treatments (such as the very elderly and those in poor health) may benefit from radiotherapy, topical immunotherapy with imiquimod (Formulary 1, p. 405) and non-surgical therapies. Figure 27.10 An example of Mohs’ micrographic surgery for an ill-defined basal cell carcinoma on the forehead near the eyebrow. (a) Initial lesion measured 10 × 8 mm. (b) After four stages of Mohs’, the lesion measured 25 × 16 mm. (c) Mohs map showing presence of tumor in red in stage 1–3 with final clearance on stage 4. (d) Reconstruction of the defect with an advancement flap and a skin graft centrally. (e) Final outcome at 6 months. Table 27.1 Features associated with high risk of tumour recurrence.

Physical Forms of Treatment

Surgery

Preparation

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Protection against blood-borne infections in dermatological surgery

Skin biopsy

Excision

Shave excision

Saucerization excision

Cryotherapy

Curettage

Electrosurgery

Microscopically controlled excision (Mohs’ micrographic surgery)

Histological and tumour features

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access