7 Photography in plastic surgery

Synopsis

Photography is not only useful, documentary, collaborative, didactic, medical-legal, a research tool and even promotional – it is standard of care and a sine qua non for proper practice in plastic surgery.

Photography is not only useful, documentary, collaborative, didactic, medical-legal, a research tool and even promotional – it is standard of care and a sine qua non for proper practice in plastic surgery.

Our specialty is highly visual and relies on accurate representation of form, as well as function, to diagnose, plan, treat, evaluate, and track patient surgical outcomes.

Our specialty is highly visual and relies on accurate representation of form, as well as function, to diagnose, plan, treat, evaluate, and track patient surgical outcomes.

The photographic record contains much more information than can be easily be documented in words, including color, tone, texture, shape, vascularity, bulk, spatial relationships of anatomic structures, global aesthetics, aging, and historical changes, to name only a few.

The photographic record contains much more information than can be easily be documented in words, including color, tone, texture, shape, vascularity, bulk, spatial relationships of anatomic structures, global aesthetics, aging, and historical changes, to name only a few.

The value of images increases with time.

The value of images increases with time.

It is difficult to imagine our specialty without the incredible utility of photography, as it is intrinsic to the visual nature of what we do.

It is difficult to imagine our specialty without the incredible utility of photography, as it is intrinsic to the visual nature of what we do.

Purpose

Much of plastic surgery rests in an unusual setting in medicine. The core and history is reconstructive in nature, largely born from efforts to rebuild injuries sustained by First World War soldiers. Whether reconstructive or aesthetic, its essence is to restore form and function, and today, a great portion is neither urgent nor critical to immediate health. Instead, much is elective and focused on quality of life, especially in the aesthetic arena. Reviewing photographs with a patient may transform the preoperative planning from an interaction tilted one way from the doctor to the patient. Instead, the effort may be collaborative and consultative, an interaction between the doctor and the patient.1,2 Various scenarios can be examined and evaluated with digital imaging, modeling and morphing. Care must be taken when showing potential postoperative results, to avoid the implication of an implied or guaranteed result.3 One popular software program (Mirror Image)4 contains an important default disclaimer at the bottom of the morphing screen, “Simulation only: Actual results may differ.”

The didactic nature of medical photography cannot be underestimated. Decades ago, sketches were used, followed by black and white photography, color transparencies and film, with the modern progression to digital images in the last 15–20 years. For all practical purposes, analog photography is a niche market and digital imaging reigns supreme. Between the consultation and the operative procedure, planning requires good recall and representation of the anatomy. The image serves to refresh the memory of the surgeon. In addition, it is critical for patients to understand excesses or deficiencies of tissues, issues of symmetry.3 Features of their anatomy may facilitate or hinder surgical planning, influence choices in surgical approach, affect risks of complications, compromise or augment patient satisfaction. Patient teaching requires proper photographic representation of the preoperative condition and explanation of the changes achieved with surgical intervention. The evolution of a surgical practice can be tracked most easily over a period of years through systematic inspection of imaging of the patients’ condition through the course of their diseases or conditions. A particularly common phenomenon is for a patient to not recall how she looked before surgery when critically viewing the postoperative result. Occasionally in reconstructive procedures and more often in aesthetic ones, the patient’s psychological “set point” is re-established at the her current condition, and the desire for further enhancement leaves her considering that not enough progress was achieved as a result of the surgery. Photos are indispensable in this setting and may provide reassurance that goals have been reached.

Maintaining proper images and consistently evaluating them postoperatively systematically can only improve awareness of surgical choices and outcomes. Properly preserved analog images may last decades with original fidelity and 100 years of more with mild degradation. Technology has evolved rapidly with digital imaging largely supplanting color film and transparency image storage. Digital images may not last much longer. Challenges in the evolution of technology lead to viewing problems (incompatibilities in hardware), scrambling issues (changes in compression algorithms), inter-relation limitations (expired webpages or hyperlinks), custodial problems (where the data resides), translation issues (how to read old storage with new technology) to name a few. If digital concerns are solved, images could last centuries or more.5 Building a digital database and engaging in periodic data mining is a core component of self-improvement in clinical care. The advent of digital photography eliminates or ameliorates concerns about lack of space, difficulties in storage like degradation of image quality, the ability to compare past and present results over large series and related issues. However, they are subject to their own vagaries. Old retrieval technologies (floppy disks, CDs, etc.) may be difficult to obtain in the near future. They are subject to catastrophic failure. For example, a scratch on a transparency may slightly degrade the quality of the image, while the same event in a digital image may make it unreadable. Digital images must be backed up and the methodologies rapidly change necessitating continual hardware upgrades. The best storage methods have changed 5–10 times in the last 20 years from floppy disk to magneto-optical disks, magnetic tape back-up, compact discs (CDs), digital video disks (DVDs), DVD RAM disks, USB flash drives, portable hard drives, network attached storage drives, and more recently, “in the cloud,” that is to say, online in a remote data storage center on the internet. Much like the evolving standards in business and research regarding storage of e-mail and digital documents for potential legal cases, our de facto standards dictate that photographs must be preserved, organized, properly referenced and identified, while easily retrievable.

Informed consent is a key part of medical record-keeping, and photography is essential to proper medical records. Almost every patient understands that photographs are part of the medical records. In fact, many insist on seeing “befores and afters” in their initial consultation, the best time to establish the necessity of accurate documentation. Some patients have a strong need for privacy; however, most surgeons will refuse to operate on a patient who refuses medical photography. Patients understand they have control and options on how their pictures will be used. Some practices allow only internal records in their private chart, others may permit sharing with other patients in consultation without identifying data, and some are comfortable with unrestricted use on the internet, in print, and television advertising. A thorough, detailed consent form specifically for the use of images is necessary for a proper medical legal record.1 Consent forms from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons are available for member surgeons.6 An additional method developed in our clinic allows granularity in designating permission of use with check boxes and a grid to supplement the verbiage in the signed form.7

Photography’s utility as a research and interpretative tool in our field is without question.8 Comparison of how our journals have progressed from the first decade of the 20th to the 21st century shows that our journals have gone from black and white to color photographs, to online digital images in low and high resolution, to online video. Three-dimensional simulations that allow a “fly through” of the anatomy have been available in recent years. Information density in images is an order of magnitude greater than the written word. With decreasing costs in the digital era, increasing use of imaging improves learning and documentation. In coming years, and perhaps even before the end of the decade, widespread use of artificial intelligence for image processing will likely allow for digital data mining of the image content itself. This would be a major advancement beyond assigning database attributes to digital files like age, preoperative, and postoperative photograph dates, type of procedure, etc. Instead, we may begin to see digital reference to quality of outcomes, conditions of anatomy on validated grading scales, etc. Even now, consumer digital cameras have “face finders,” automated red-eye reduction and similar tools. Professional systems have capabilities like automatic pore evaluation on the skin and cell counters for microscopic work. One could imagine many future potential applications like automatic color detection, evaluation of cutaneous vascularity, flap perfusion and others.

Since the mass “migration” to the internet by the general population, the public has turned online to research plastic surgery, compare results, investigate complications, nurture special interest groups and procedures, and engage in promotion and marketing. There are many egregious examples of excess, manipulation and deception; however, there are even more beneficial opportunities for patient education, practice marketing, advocacy and public health outreach. In addition, surgeons often disregard photographic documentation standards of care.9

Standards in capturing images

Little has changed for the framing and composition of images since Morello et al.10 and Zarem11 and many before them specified these aspects of photographic standards in plastic surgery. However, many other factors have evolved in the transition to the digital world.12 Key principles (see above) must be followed.13 Consistency in results is affected by numerous factors.8,10,11,13 Facial photographs are taken at the 100 mm lens digital 35 mm camera equivalent, while body images are taken at the 50 mm lens equivalent.14 Shadows are to be avoided. Colors must be natural. Lighting should be unobtrusive and consistent. Standards must be obeyed.15,16

Key principles

• The same camera should be used. Changing a digital camera (and therefore the color and white balance) essentially alters the pixel resolution, photonic sensitivity and hardware image processing.

• Shutter speed and aperture must remain the same. Positioning of the patient and photographer in the room should not vary.

• Guide marks on the floor may be required; flash equipment and lighting should not vary.

• Adequate lighting is essential. Shutter speed should be at 1/60 of a second or faster.

• On digital cameras, keep the magnification factor the same that is comparable with a 35 mm camera 100 mm lens for essentially all images except full body views, where a view comparable to a 50 mm lens may be used.

• Focus by moving the camera closer or farther from the patient and note the position of the mechanized zoom lens barrel in relation to the camera body.

• Do not change the white balance and keep it in synch with the lighting used (often flash or fluorescent) on a medium blue background.

• While modern cameras often contain 10 megapixels or more, generally more than five are not required.

• Space for digital images is not an issue in this era of terabyte hard drives, and the speed is easily adequate for rapid access of data.

• More images than will likely be used in a career can be stored on light, portable drives.

Digital image characteristics

Many variables affect images, and many are in control of the plastic surgeon. Parker et al.8 have documented four basic ways in which inconsistency is introduced into photography: (1) photographer-based; (2) publisher-based; (3) combined; and (4) patient-based. Category 1 in their scheme includes view (composition), background and zoom and are generally consistent in a variety of journals. Publisher-criteria, size and image labeling are less problematic. Combined criteria, color, brightness, contrast, and resolution vary in published journals. Category (4) criteria: clothing, accessory apparel, make-up, facial expression, and hairstyle, are designated as patient-based, but are substantially under the control of the photographer. A dark colored drape can be used over the shoulders for facial photographs. Accessory apparel should be removed, as make-up, false eyelashes, and similar accoutrements of fashion may interfere. Hairstyle can be mitigated by using standardized hairbands or ties.

Galdino categorizes factors into direct and indirect.12,13 Direct variables include lens, viewfinder, digital chip, resolution, compression and software algorithms of the camera. Indirect are listed as lighting, metering, depth of field, color temperature of lighting and output method. Both categories are easily controlled by remaining consistent techniques from visit to visit.

Composition and positioning

Full face

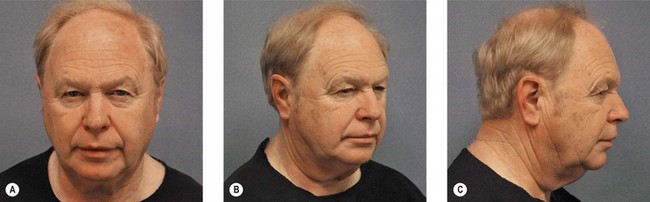

In the anterior-posterior (AP) view, the superior border of the head must be framed by a small amount of background, about 10% of the vertical height of the image. The inferior border of the image should stop near the level of the suprasternal notch. In the lateral view, the patient’s body and head should be facing 90° from the focal plane of the camera. While some cropping of the occipital region is acceptable, in general, lateral views should include the full view. Oblique views should be taken at 45° and, in this view; the tip of the nose should protrude slightly beyond or rest just at the contour of the distal malar eminence. Five standard views are taken, an AP, two oblique and two lateral, right and left for each of the latter two (Fig. 7.1). When indicated, the malar eminence may be imaged, generally the bird’s eye view is preferred over the worm’s eye view, unless a particular feature of anatomy is involved.

Musculature should be relaxed in all photographs unless otherwise specified.

Eyes

The same five image views (anterior, two laterals and oblique views) are part of the basic set for the eyes. Close-up images of the eyes should include a small border of forehead skin above the eyebrows and extend inferiorly to the upper lip at the nasal spine. For the lateral and oblique views, positioning is similar to the views of the head honoring the superior and inferior borders herein. Additional views are essential and include the following at a minimum: (1) closed eye view to highlight the superior tarsal sulcus and fold, and (2) upward gaze to highlight inferior orbital fat pockets and the lower lid margin. A squinting view consists of open eyelids with contracting of the superior and inferior orbicularis oculi to feature the impact of muscle action on eyelid shape and function. Occasionally, a view with tightly-closed eyelids to highlight the orbital orbicularis, zygomaticus muscles and others is required for certain surgical procedures (Fig. 7.2).