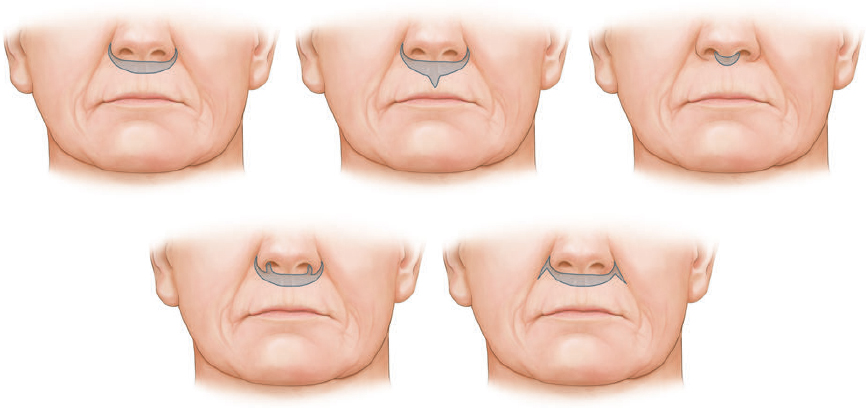

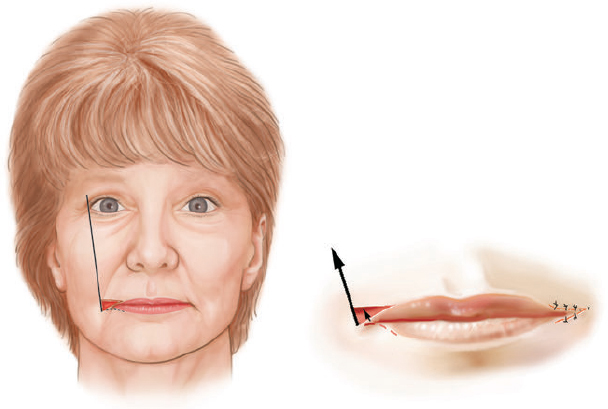

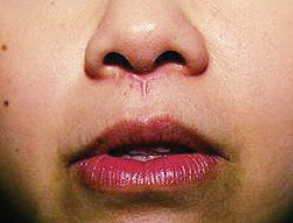

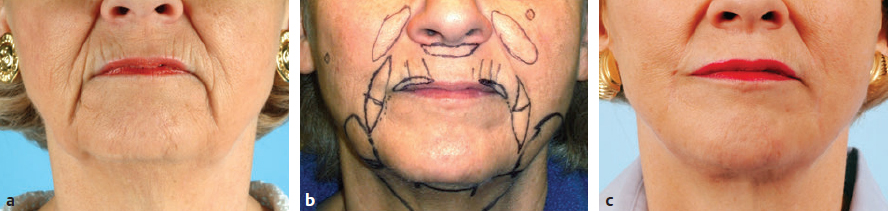

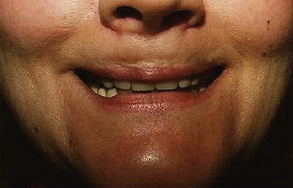

CHAPTER The perioral region has traditionally been ignored or undertreated as a part of facial rejuvenation, despite being a key element of facial beauty. Although not every patient considering a facelift is a candidate for perioral surgery, a significant number would benefit from some sort of perioral procedure. A key difference with regard to perioral surgery is that most patients do not know they would benefit from it. A patient with small breasts asks for larger breasts. A patient with a large nose knows they would like it made smaller. But a patient with an aging face rarely recognizes the mouth as a contributing factor. Leaving an aged mouth untouched when surgically addressing the rest of the face leaves a result that is disharmonious, unnatural, and “done.” With age, the upper lip lengthens, covering the upper incisors. The corners of the mouth droop. The vermilion thins, deflates, and rolls inward. The philtrum flattens and disappears. Nasolabial and marionette folds form and deepen. Each of these changes in perioral anatomy is symbolic. A thin lip may mimic rigidity. A downturned mouth corner signifies displeasure. Deep folds are associated with age. Yet although a patient’s facial appearance may “show” a negative emotion, this does not necessarily match their internal emotional state. It is this incongruence that leads patients to seek plastic surgery. Perioral surgery aims to align the internal state with the external symbolism. Although the mouth is occasionally surgically addressed alone, it is usually one component of a larger facial surgical rejuvenation. Adding volume to the face is currently in vogue, especially the lips. This trend is spurred by societal trends, but also by non–plastic surgeon practitioners who have filler as one of their limited number of tools to rejuvenate the aging mouth. This single-minded strategy toward perioral rejuvenation has led to new complications of overfilling and injection sequelae and usually does not address the other underlying signs of aging. The burden is on the surgeon to not only diagnose an aged mouth as part of the overall issue, but to be able to discuss with the patient during the consultation why not addressing the mouth at the time of facial rejuvenation is potentially a setup for dissatisfaction because of a lack of balance and facial harmony. Surgical planning must take into account whether the perioral issues to be treated will require volume, skin resurfacing, direct surgical incisions, or a combination of any or all to achieve harmony. This chapter focuses specifically on perioral surgery to include the lip lift, corner mouth lift, vermilion advancement, and direct excision of nasolabial folds and marionette lines. It also discusses how to avoid complications when performing these procedures. Plastic surgeons have been reluctant to place incisions around the mouth and lips for cosmetic reasons, but we believe this is a mistake. A surgeon will place a scar directly on the eyelid to rejuvenate the eye, or directly onto the face to rejuvenate the cheek, and it follows that an incision is often needed around the mouth to rejuvenate the lips. A facelift cannot be pulled tight enough to smooth a deep nasolabial fold, and a midface lift will not change the position of the oral commissure. Direct surgical approaches are required to remove the sequelae of aging from the perioral region. Lip lifting procedures were first presented in the 1970s by the Brazilians,1 and we have been using them successfully at our practice since the early 1980s to shorten a long upper lip,2 with proven effect.3 The procedure uses a surgical incision just beneath the nostril sill to remove skin from the upper lip, and although there are several variations, the general concept is the same in all4 (Fig. 27.1). The goal of the corner mouth lift is to again make visible the vermilion of the upper lip near the commissure that becomes hidden with age. A “wraparound” can be added to lift a downturned commissure at the expense of a scar that extends around the commissure4 (Fig. 27.2). The main goal of a vermilion advancement procedure is to expose more vermilion of the lower lip by placing a surgical incision along the vermilion border and removing adjacent nonvermilion skin, effectively advancing the vermilion to a more visible position. Because this is performed in patients whose lip has collapsed inside the mouth with age, the postoperative aim is returning the lip tissue to its normal anatomic position. Wet mucosa is not advanced beyond its normal border. Lip advancement can be done on the upper and lower lips, although scarring is more acceptable on the lower lip and on the lateral portions of the upper lip. Fig. 27.1 A variety of lip lift excision patterns are shown in gray. (Reproduced from Nahai F. The Art of Aesthetic Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2016.) Fig. 27.2 Wraparound corner mouth lift. The upper incision is placed along the upper vermilion border and extended medially, not to cross the philtral column. The lower incision allows the commissure to be lifted, the skin resection above the upper lip allows more upper vermilion show, resulting in a final scar that wraps around the corner of the mouth. (Reproduced from Nahai F. The Art of Aesthetic Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2016.) The goal of direct excision of nasolabial and marionette folds is to remove the deep and stubborn folds using direct incisions and replace them with a flat and hidden scar (Fig. 27.3). Summary Box Most Common Complications in Perioral Surgery • Visible scar • Scar contracture • Underdone result • Overdone result • Asymmetry of lift • Infection Most unfavorable results after perioral surgery result from either (1) choosing the wrong patient or (2) choosing the wrong procedure. The right patient for surgery is willing to accept a scar for a more harmonious result. Illustrating this to the patient with high-quality before and after photographs of other patients is critical. The trade-off for perioral surgery is an imperceptible scar at conversational distance for a more youthful mouth. The ideal patient is older, because the scars tend to be better in these patients. Caution is suggested in young patients with a propensity to form hypertrophic scars (Fig. 27.4). In general, perioral surgical scars heal well and are barely noticeable. Caution should be exercised in those with a history of poor scarring. When evaluating the perioral region, the surgeon should note the length of the upper lip, the visibility of maxillary teeth, the ratio of upper lip skin to vermilion, the ratio of upper lip vermilion to lower lip vermilion, the position of the corners of the mouth, perioral wrinkling, lip deflation, wrinkling or creases, and occlusal class. An analysis of a typical patient is presented Fig. 27.5 along with her postoperative result. Another patient undergoing liplift and corner mouth lift is shown in Video 27.1 with analysis of anatomy, surgical markings, intraoperative snippets, and early and late postoperative results. Fig. 27.3 (a) This patient was seen preoperatively for direct excision of her marionette folds. Her left fold was longer and deeper and branched distally. She also wore lipstick below the true vermilion margin of her lower lip, in essence mimicking a vermilion advancement. (b) After undergoing direct marionette fold excision, typical scars are seen. These are visible at 3 months from very close without makeup but are nearly imperceptible at conversational distance. With time the scar improves and becomes more inconspicuous. Fig. 27.4 This patient underwent a lip lift with a central component to shorten a long upper lip and make a more prominent Cupid’s bow. She had a hypertrophic scar postoperatively that was very visible and was treated with injectable steroids and topical silicone until resolution. There are certain characteristics that make a scar more visible, and these need to be identified in advance so realistic expectations can be set. For example, in patients being considered for a lip lift, the surgeon must examine the patient from a lateral viewpoint to judge the nasolabial angle. An obtuse angle means the scar will be more visible on frontal view.5 Similarly, the sill of the nose must be evaluated before the lip lift. In patients with a blunted sill anywhere along the nasal base, a scar in that area will be more noticeable. Both of these cases are illustrated in Fig. 27.6. This patient has an ill-defined sill beneath the columella and an obtuse nasolabial angle. Without a defined sill beneath the columella, the scar will be present as a fine line where there was previously not one. Although not having sill definition, often in the setting of an obtuse nasolabial angle, is not ideal, it is not a contraindication to a lip lift. The patient must be counseled preoperatively about the scar visibility. Rhinoplasty can be safely performed at the time of lip lift and can enhance sill definition to better camouflage the scar. For a patient with a well-defined sill beneath the columella but a blunted sill beneath the nares, the scar can be carried intranasally to camouflage it in an already-blunted location. When considering a patient for a lip lift, simply having a long lip is not by itself an indication. A patient with a long lip also needs to have minimal or no incisal show. If a patient has significant incisal show, regardless of the lip length, there is a risk of giving the patient the appearance of vertical maxillary excess if the lip is significantly shortened. Although the lip height is determined on a case-by-case basis, one general consideration is that an upper lip should not be shortened beyond 10 mm, because this can produce facial disharmony. The patient in Fig. 27.7 has incisal show at rest and also has a long upper lip. This means only a conservative resection can be performed to prevent the patient from showing too much incisor. Fat grafting along the distal vermilion border at the time of lip lift can increase the red vermilion height and create more tooth coverage. If there is inadequate red lip vermilion to accept fat grafting, an intraoral mucosal advancement of wet vermilion can be performed, but this is rarely used in our practice.6 For a patient with inadequate incisal show and a lip Fig. 27.5 (a) This patient exhibited typical signs of perioral aging. She had a long upper lip, a well-defined nasal sill, loss of vermilion show near the commissures, prominent and asymmetrical nasolabial and marionette folds, multiple vertical lip rhytids, and overall thin lips with a relatively normal ratio of upper to lower vermilion height. (b) The same patient with markings for a lip lift, corner mouth lift, direct marionette excision, fat grafting to the perioral rhytids, and facelift with liposuction of the face and neck. (c) At 3 months postoperatively the scars around her mouth are nearly imperceptible. The deep marionette folds and distal nasolabial folds are obliterated by excision. The proximal nasolabial fold above the excision pattern is still quite deep. The patient declined fat grafting or lower lip advancement for fear of looking operated. Fig. 27.6 (a,b) This patient was seen preoperatively for a lip lift. Note the ill-defined sill, incisal show in repose, and obtuse nasolabial angle along with multiple perioral rhytids and deflated lips. (c) After a lip lift and fat grafting. Her overall perioral aesthetic is improved, but this case illustrates the potential for lip lift scar visibility in patients with an obtuse nasolabial angle and the need for a conservative lift along with fat grafting in the distal vermilion margin in patients with preoperative incisal show. shorter than 10 mm, cosmetic dentistry to lengthen the teeth is a good option. A long lip must be assessed as part of the global mouth and face. If a long lip with downturned corners undergoes lip lift alone, the Cupid’s bow can become too lifted relative to the corners, producing a doll-like mouth that is unnatural. By evaluating the mouth in detail and as an overall component of the facial aesthetic, the correct procedure can be chosen for the patient. Fig. 27.7 (a) This patient was seen preoperatively for a wraparound corner mouth lift. She had downturned corners extending into marionette folds and the associated unpleasant symbolism. (b) Postoperative result. This case illustrates the power of the wraparound corner mouth lift to lift the commissure into an overdone position. Her marionette folds are improved, and with the lifted corners, the grumpy symbolism is gone. When assessing a patient for a corner mouth lift, there are two key anatomic components to consider. First is the position of the vermilion as it approaches the commissure. With age, the vermilion of both lips disappears laterally near the commissure, and part of a corner mouth lift is making the upper lip vermilion more apparent and youthful. Second, special attention must be paid to any downturn of the commissure. If the commissure has significant droop, then a wraparound corner mouth lift (see Fig. 27.2) can address the commissure as well as the disappearance of the upper vermilion near the commissure. This can be a powerful procedure, and there is potential to overdo the result by turning up the corners too much (see Fig. 27.7). If the commissure does not appear low but the vermilion disappears laterally approaching the corner of the mouth, a standard corner mouth lift without a scar that wraps around the commissure may be performed. This is a gentle elliptical excision of skin only. As long as the lower portion of the resection margin is placed exactly at the junction of the vermilion, the scar heals well. Any diversion from the surgical plan that takes a scar out laterally from the commissure, and thus at a 90-degree angle to the nasolabial fold, is noticeable and should be avoided.7 There is a degree of relaxation postoperatively after a corner mouth lift, although less so than with a lift lip, which relaxes significantly (Fig. 27.8). The on-the-table result should be slightly overdone to account for this.8 A result that looks perfect in the operating room will appear underdone in several months (Fig. 27.9). Fig. 27.8 This patient underwent isolated lip lift and is seen preoperatively (a), with markings (b), at 1-week suture removal (c), and at 3 months postoperatively (d). The long upper lip had visible lower incisors preoperatively, with a transition to upper incisor show postoperatively. The degree of relaxation is significant and must be accounted for during surgical planning. Fig. 27.9 This patient is seen preoperatively (a) and postoperatively (b) after a lip lift and corner mouth lift. Although her aesthetic is improved, both procedures are slightly underdone. The upper lip is still slightly long without incisal show in repose, and the corner lift does reveal more vermilion out toward the commissure, but is underdone by approximately a millimeter. These results were underdone by not accounting for the degree of postoperative relaxation that typically occurs. Fig. 27.10 This patient underwent upper lip advancement all the way across the vermilion border from commissure to commissure. It resulted in an unnatural and operated look by surgically creating a Cupid’s bow with direct excision. A surgical incision should generally not be placed across the Cupid’s bow. Fig. 27.11 This patient underwent upper lip advancement with an incision spanning from commissure to commissure across both Cupid’s bows. She has a contracted scar postoperatively that is extremely distorting on animation. For this reason, an incision across the Cupid’s bow is not recommended. Vermilion advancement is also a powerful procedure and aims to “roll out” the collapsed and deflated appearance of the vermilion that happens with age. Along the lower lip, the scar at the red junction is well tolerated and nearly imperceptible. Caution should be exercised along the upper lip, because crossing over the Cupid’s bow can leave an unnatural appearance (Fig. 27.10). If the scar along the peaks of the bow does contract and become tight, the scar is nearly impossible to correct (Fig. 27.11). Surgeons have shown good results with upper lip advancement,9 but the potential for disfigurement has led us to abandon advancement of the central upper lip. For a patient with collapse of the upper vermilion along the entire width of the lip, there is almost always also a long upper lip, and a combination of lip lift and corner mouth lift with fat grafting is then our procedure of choice. It is a matter of experience to determine whether volume correction with fat grafting alone will completely resolve a deep fold around the mouth,10 or whether direct excision is required. Often patients may be reluctant to undergo direct excision of nasolabial or marionette folds at the time of facial rejuvenation because of the concern of what the scar will be like, and surgeons unfamiliar with direct excision are unable to disabuse them. It is reasonable to blunt a deep nasolabial or marionette fold with fat grafting alone at the time of facial rejuvenation with the understanding that a later procedure may be required. As long as the patient understands the fold may not be alleviated by volume alone and that a secondary procedure is a possibility down the road to directly excise the fold under local anesthesia, the patient expectations are set and they will not be disappointed after surgery if an excision needs to be secondarily performed. For those patients who are willing to have a small facial scar for a more dramatic improvement, it is important to perform the direct excision portion of the procedure before the facelift. Once the direct excision is performed and closed, the facelift can be performed to the normal desired tension without risking a wound that is too tight to close. One useful tool to determine whether excess skin exists at the lower face that might require excision is to mimic the lift achieved with a facelift by holding gentle traction in front of the ear. If there is significant redundant skin while mimicking the facelift, it is unlikely that facelift and nasolabial volume alone will correct the deep furrows around the mouth. This patient can be counseled about the possibility of having a direct excision at the time of facelift or as a secondary procedure. Markings of the direct excision have been described previously.4 The ideal scar position is chosen, and then a stretch technique is used to mimic the amount of desired effect. Holding a marking pen at the ideal scar position and then releasing skin stretch, allowing the pen to drag along the skin, sets the appropriate margin of resection. The final markings resemble an ellipse (see Fig. 27.5b,c).

27

Perioral Aesthetic Surgery

Basic Procedures for Perioral Surgery

Lip Lift

Corner Mouth Lift

Vermilion Advancement

Direct Excision of Nasolabial and Marionette Folds

Avoiding Unfavorable Results and Complications in Perioral Aesthetic Surgery

Lip Lift

Corner Mouth Lift

Vermilion Advancement

Direct Excision of Nasolabial and Marionette Folds

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine