17 Perineal reconstruction

History of perineal reconstruction

The evolution of perineal reconstruction over the last century parallels the development of the reconstructive ladder. Since Miles described abdomino-perineal resection in 1910 for carcinoma of the rectum, numerous methods of reconstructing the perineum have been described. In his original paper, the perineal wound was simply packed with gauze, with closure by secondary intention or delayed primary closure.1 This led to significant morbidity associated with an open perineal wound, and Altmeier et al. subsequently introduced the concept of primary closure of the perineal wound with continuous suction drainage.2 Although there was some degree of success with both primary and secondary closure of the perineum, certain perineal wounds seemed predisposed to breakdown, particularly those that were irradiated and contaminated. Brunschwig’s introduction of pelvic exenteration provided the potential for oncologic cure, but left an even larger pelvic defect with significant associated morbidity.3 Management of the draining perineal wound proved difficult; split thickness skin grafts were attempted with limited success.4

The advent of axial-pattern flaps ushered in the next rung on the reconstructive ladder for perineal reconstruction. Although first applied in coverage of exposed bone in the lower extremity, muscle flaps were soon utilized throughout the body, including the perineum.5 The gluteus maximus flap was described as a potential cure for a chronic perineal sinus.6 The rectus abdominus flap subsequently emerged to be a workhorse in perineal reconstruction.7,8 Transverse, vertical and oblique skin paddles have been designed and used effectively. The gracilis muscle has also been described extensively for use in the perineum.9,10

More recently, fasciocutaneous flaps have been reported for perineal reconstruction. Wee introduced the concept of neuro-pudendal thigh flaps for vaginal reconstruction, creating sensate lining for the vaginal wall.11 The anterolateral thigh flap has emerged as a versatile flap that can be applied to perineal reconstruction as well as complex pelvic wounds.12,13

Finally, advances in microsurgery have allowed free flaps to be performed routinely with reliable results. Although the utility of free flaps in perineal reconstruction has been somewhat limited by the ample loco-regional flaps available, there have been reports of free flaps for coverage of large defects in the perineal area, particularly in conjunction with sacral defects.14 Moreover, microsurgical techniques developed over the last decade have allowed perforator flaps to be applied to this region of the body as well. Both inferior and superior gluteal artery perforator flaps have been utilized for perineal coverage.15

Basic science/disease process

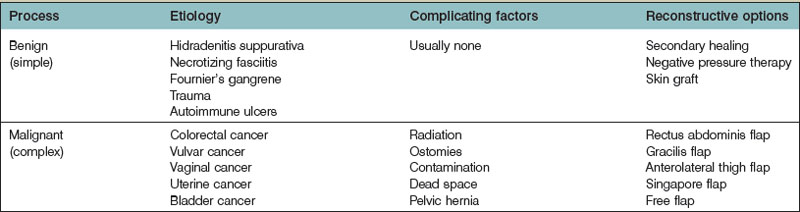

The processes requiring reconstruction of the perineum can broadly be broken into benign and malignant processes (Table 17.1). Benign conditions primarily include hidradenitis suppurativa, infectious destructive processes such as fasciitis or Fournier’s gangrene and trauma, but can range to other rarer dermatologic conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum and vasculitic ulcers. These entities have in common the depth of involvement, which typically leaves an external cutaneous deficit on the perineum (see Figs 9.13, 9.18). Once the primary process is addressed and resolving, the defect can begin secondary healing, although negative pressure therapy and skin grafts can often play a useful role in shortening the time to healing.

Malignant diseases include colorectal cancer, urologic and gynecologic cancers, which originate from and involve deeper structures (see Figs 9.11, 9.12). Abdominoperineal resection or exenteration has been demonstrated to provide the best cure in these cases. Typically, this extensive resection is accompanied by peri-operative radiation therapy. Treatment of these more complex defects must be individualized for the missing and exposed structures. Impediments to healing such as fistulas and radiation changes in the area generally mean these defects will not heal without the addition of a nonradiated tissue transfer. Large areas of dead space after extensive resection can allow the abdominal viscera to fall into the irradiated pelvic basin. This can lead to adhesions, obstruction, and fistulas, which can be disastrous to treat secondarily. Nearby organs such as the bladder or vagina may also be resected in part or whole as part of the treatment course.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Patients with benign disease may present at various stages in their treatment. As a rule, reconstruction should not be initiated until the primary process is identified and resolved with repeated surgical debridements or excisions; underlying medical conditions or autoimmune disorders should be treated. Typically, areas of external perineal skin are involved and will require resurfacing in some fashion (Fig. 17.1).

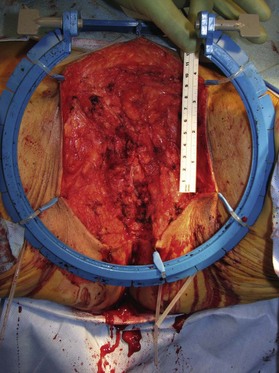

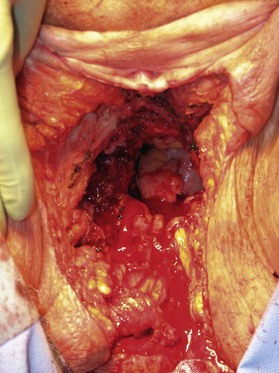

Patients with malignant disease are typically treated in conjunction with a multidisciplinary oncologic team. Often the extent of the defect is not obvious until after the surgical resection is performed. Preoperative consultation is important to manage patient expectations, outline the possible extent of surgery and prepare for postoperative adversity. Such cases may involve more extensive external pudendal defects (Figs 17.2, 17.3) or deeper structures (Fig. 17.4). In the event that vaginal resection is necessary, preferences regarding vaginal versus simple perineal reconstruction should be discussed, along with a thorough dialogue about sexual function. Further details and management of vaginal reconstruction is discussed in depth in Chapter 14.

Patient selection

In the case of malignancy, radiation therapy is part of the preoperative routine in most centers. This factor alone is the most significant indication for flap reconstruction at the time of resection. Large prospective series suggest that abdominal based flaps demonstrate the most favorable outcomes and mildest complication profile in this setting, even compared to thigh flap reconstruction.16 This must be balanced with the abdominal morbidity of the harvest. Some surgeons prefer to avoid using abdominal flaps if ostomies are necessary on both sides, although these can be inset through the external oblique musculature with no additional morbidity. A vertical skin pedicle provides the most discreet scar, but an oblique paddle can provide more bulk extending off the muscle, effectively extending its reach also. Preexisting abdominal wall defects might direct some surgeons to alternative flap options. Nevertheless, Butler has shown no increased incidence of abdominal wall problems after abdominal flap harvest.16,17 Rarely, perineal resection can be performed without laparotomy and this might predispose toward use of a nonabdominal flap option.

The complication profile of the gracilis flap is also reasonable, and represents a dramatic improvement over primary closure under these circumstances. Early studies comparing gracilis reconstruction to primary closure demonstrate a dramatic reduction in infectious complications from 46% to 12% with flap reconstruction.18

Some surgeons favor a posterior thigh flap, harvested in similar fashion to the anterolateral thigh flap, but the axial nature of the perfusion off the inferior gluteal artery has been called into question. Recent series document over a 50% wound healing complication rate using this method,19 which does not compare favorably to abdominal flaps.

For defects with less dead space or requiring less bulk, Singapore flap reconstruction can be used, although outcomes data are more mixed and overall less favorable compared with abdominal flaps. Complications are reported to range from 7% to 62%.20–22 Recent outcome studies are not available directly comparing this method to other options in head-to-head fashion.

Massive defects in pelvic support may in fact require multiple flaps. Occasionally pelvic floor support is needed in the form of mesh reinforcement. In a hostile, radiated, often contaminated surgical site, prosthetic mesh is contraindicated. Newer bioprosthetic options provide a reinforcement alternative that is more robust in the face of complications.23

Treatment/surgical technique

Skin graft reconstruction

Benign, uncomplicated wounds of the perineum that granulate in response to dressing changes or negative pressure therapy can usually be treated in staged fashion with split thickness skin grafts. However, managing these uncomplicated wounds with either negative pressure therapy or dressing changes is also a viable option. If the latter route is chosen, hydrotherapy and/or routine follow-up via a wound care center would be advised to monitor for infection, tissue necrosis or both which would require further debridement. With supportive patient counseling, particularly in cases of debridement for hidradenitis suppurativa or similar etiology of wounds, dressing changes and observant management can be an effective method of therapy (Fig. 17.5).

Regional skin flaps

Processes such as Fournier’s gangrene may leave more extensive but still subcutaneous defects that can be reconstructed with local flaps. Exposed subcutaneous structures such as testes can be buried under nearby intact skin if available. These adjacent areas of intact skin on the thighs or perineum can also be advanced using a V-Y pattern, rotational or keystone design to provide resurfacing (Figs 17.6, 17.7). Some authors have described tissue expansion in conjunction with regional flaps to augment the amount of subcutaneous coverage available for example in the case of missing scrotal coverage.24 Even perforator-based flaps have been described in this setting using medial circumflex femoral vessels25 and profunda femoris perforating branches.26