Introduction

Inflammation in subcutaneous fat often poses a diagnostic problem for clinician and pathologist alike, since the clinical and histopathological findings in the various inflammatory disorders of adipose tissue (AT) have overlapping features. Specificity in diagnosis is potentially difficult since similar clinical presentations are sometimes associated with disparate histopathological features. Diagnostic problems may also relate to the corollary observation that a range of clinical presentations may have similar histopathologic findings.

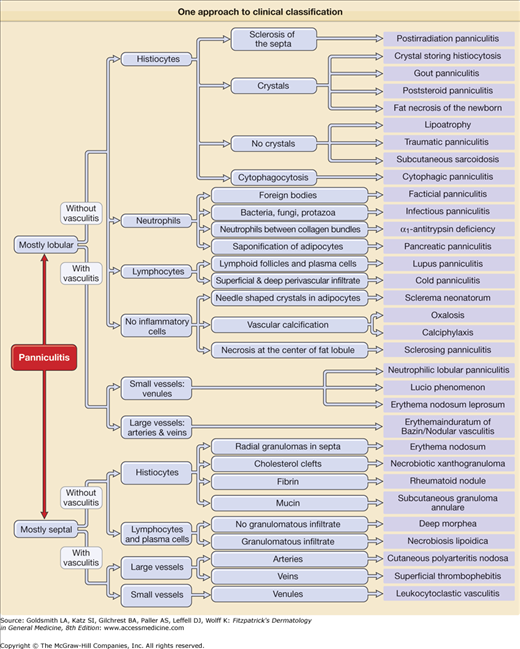

There is no universally accepted classification of panniculitis, but from the point of view of many pathologists, a useful classification begins by dividing panniculitis into septal and lobular forms, “septal” signifying inflammation confined predominantly to the septa, and “lobular” indicating inflammation predominantly involving the fat lobule itself. The septal form has been most classically associated with erythema nodosum (EN) and the lobular form with all or most other types of panniculitides. But even this beginning point has not been proven adequate since lobular granulomatous panniculitis may be seen in clinically classic EN,1 and lobular panniculitides may have mixed lobular and septal inflammation.2 This classification has been expanded by making note of the presence or absence of vasculitis in the septa or lobules,3 by the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate, and by additional specific features when present (Fig. 70-1).

Since diverse clinical conditions may be expressed by similar histopathologic features, and the spectrum of histopathologic features in EN and other panniculitides may be variable,4 it may not be possible to make a specific diagnosis of panniculitis based on histopathology alone. This necessitates correlation with clinical features, including location of lesions, systemic symptoms, laboratory findings, and etiological factors. A significant aid to success in the diagnosis of inflammation in AT is obtaining a tissue sample that will adequately represent the histopathologic changes in the lesion. This can only be done with large excisional biopsies, as small punch biopsies are unlikely to obtain adequate AT, and the inflammatory infiltrate can be missed. An additional consideration is that inflammation in AT is not a static process, and as samples taken at different stages of an evolving lesion will present with different histopathologic features, more than one biopsy may be necessary to come to a conclusive diagnosis.

Under the best of circumstances, with optimal histopathologic sampling and clinical correlation, there may be no specific etiology for many inflammatory reactions in AT. But even with a specific diagnosis or etiology, underlying questions remain. Why were the inflammatory cells accumulating in the AT? What were they doing there?

Adipose Tissue and Immunity

![]() In the past 20 years, research into obesity has led to a great deal of information about the function of adipocytes and AT, and to the understanding that adipocytes are central not only to energy homeostasis but also as cellular components of the innate immune system and mediators of inflammation. AT is an immunological active organ system that lies at the crossroads of multiple important physiological functions, including energy expenditures, appetite, insulin sensitivity, endocrine and reproductive systems, bone metabolism, inflammation, and immunity.5

In the past 20 years, research into obesity has led to a great deal of information about the function of adipocytes and AT, and to the understanding that adipocytes are central not only to energy homeostasis but also as cellular components of the innate immune system and mediators of inflammation. AT is an immunological active organ system that lies at the crossroads of multiple important physiological functions, including energy expenditures, appetite, insulin sensitivity, endocrine and reproductive systems, bone metabolism, inflammation, and immunity.5

![]() Millions of invertebrate species rely solely on the innate immune system as defense against infections.6 A hallmark of insect antimicrobial defense is the organ called the fat body, which has receptors for bacterial and fungal cell wall molecules known as Toll receptors. These receptors activate the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling cascade, inducing secretion of antimicrobial peptides and other defensive molecules.7 The insect fat body is analogous to the mammalian liver and in addition to the immune functions, also manages the animals’ liver functions and lipid storage.8 Subsequently, in the evolution of vertebrates, these functions were divided up between the liver and the AT, with the latter retaining some functions of the innate immune system.8

Millions of invertebrate species rely solely on the innate immune system as defense against infections.6 A hallmark of insect antimicrobial defense is the organ called the fat body, which has receptors for bacterial and fungal cell wall molecules known as Toll receptors. These receptors activate the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling cascade, inducing secretion of antimicrobial peptides and other defensive molecules.7 The insect fat body is analogous to the mammalian liver and in addition to the immune functions, also manages the animals’ liver functions and lipid storage.8 Subsequently, in the evolution of vertebrates, these functions were divided up between the liver and the AT, with the latter retaining some functions of the innate immune system.8

![]() As a cell of the innate immune system, the adipocyte is equipped to protect the organism from pathogenic microbes by recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via receptors called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs).9 There are three types of PRRs: (1) transmembrane, (2) cytosolic, and (3) secreted.9–11 Transmembrane PRRs include Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectins.11 TLRs are expressed either on the plasma membrane where they detect cell surface microbial patterns such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, or in endosomal/lysosomal organelles, where they recognize mainly microbial nucleic acids such as dsRNA (TLR3), ssRNA (TLR7), and dsDNA (TLR9).11 Expression of TLRs is cell-type specific, thereby allocating recognition responsibilities to different types of cells.11

As a cell of the innate immune system, the adipocyte is equipped to protect the organism from pathogenic microbes by recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via receptors called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs).9 There are three types of PRRs: (1) transmembrane, (2) cytosolic, and (3) secreted.9–11 Transmembrane PRRs include Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectins.11 TLRs are expressed either on the plasma membrane where they detect cell surface microbial patterns such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, or in endosomal/lysosomal organelles, where they recognize mainly microbial nucleic acids such as dsRNA (TLR3), ssRNA (TLR7), and dsDNA (TLR9).11 Expression of TLRs is cell-type specific, thereby allocating recognition responsibilities to different types of cells.11

![]() C-type lectins dectin-1 and -2 recognize β-glucans and mannan of fungal cell walls.11 Cytosolic or internal PRRs consist of nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing receptors (NLRs) which include the large NOD receptor family, and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-1)-like receptors (RLRs), and recognize PAMPs in the internal compartment should the microbe evade extracellular surveillance.11,12 Secreted PRRs include collectins, ficollins, and pentraxins which bind to the surface of microbes, activate the complement system, and opsonize microbes for phagocytosis.11

C-type lectins dectin-1 and -2 recognize β-glucans and mannan of fungal cell walls.11 Cytosolic or internal PRRs consist of nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing receptors (NLRs) which include the large NOD receptor family, and retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-1)-like receptors (RLRs), and recognize PAMPs in the internal compartment should the microbe evade extracellular surveillance.11,12 Secreted PRRs include collectins, ficollins, and pentraxins which bind to the surface of microbes, activate the complement system, and opsonize microbes for phagocytosis.11

![]() Once activated, the PRRs activate proinflammatory signaling pathways, especially activation of transcriptions factors NF-κB, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), or nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), that promote expression of genes involved in the immune response mediated via multiple molecules including cytokines, chemokines, antimicrobial peptides, complement, adhesion molecules, and cell membrane costimulatory molecules.11,13 TLRs trigger activation of adaptive immunity responses that include antibody responses, TH1, TH17 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells responses, and TH2 (via TLR4) and IgE response.11 Cytosolic PRRs including RLRs and some NLRs may also activate adaptive immunity.11

Once activated, the PRRs activate proinflammatory signaling pathways, especially activation of transcriptions factors NF-κB, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), or nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), that promote expression of genes involved in the immune response mediated via multiple molecules including cytokines, chemokines, antimicrobial peptides, complement, adhesion molecules, and cell membrane costimulatory molecules.11,13 TLRs trigger activation of adaptive immunity responses that include antibody responses, TH1, TH17 CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells responses, and TH2 (via TLR4) and IgE response.11 Cytosolic PRRs including RLRs and some NLRs may also activate adaptive immunity.11

![]() Adipocytes are the most abundant cells in white AT (WAT), but other cell types are included in the stromovascular fraction, including fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells, especially macrophages which makes up 10% of that fraction but increase significantly in obesity.5 These macrophages along with other stromovascular cells contribute to the production and secretion of humoral cytokines, especially the inflammatory cytokines.5,14 The macrophages are bone-marrow-derived from circulating monocytes infiltrating WAT, and incubation with adipocyte-conditioned media leads to increase in intercellular adhesion molecule I (ICAM-1) and platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (P/E CAM-1) in endothelial cells, leading to increased transmigration of blood monocytes to AT.15,16 The same effect is seen with high-dose leptin and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1).5 Macrophage-derived TNF induces adipocyte lipolysis, which leads to release of free fatty acids from the adipocyte, which induces direct TLR4 signaling and NF-κB activation in macrophages.10 This paracrine loop involving inflammatory cytokines and free fatty acids establishes a vicious cycle between adipocytes and macrophages that propagates inflammation.17 Glucocorticoids and thiazolidinendiones have been shown to interfere with adipocyte mediated macrophage chemotaxis and recruitment.18 Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce the proinflammatory status of mature adipocytes by inhibiting basal release of MCP-1 and resistin.19

Adipocytes are the most abundant cells in white AT (WAT), but other cell types are included in the stromovascular fraction, including fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells, especially macrophages which makes up 10% of that fraction but increase significantly in obesity.5 These macrophages along with other stromovascular cells contribute to the production and secretion of humoral cytokines, especially the inflammatory cytokines.5,14 The macrophages are bone-marrow-derived from circulating monocytes infiltrating WAT, and incubation with adipocyte-conditioned media leads to increase in intercellular adhesion molecule I (ICAM-1) and platelet–endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (P/E CAM-1) in endothelial cells, leading to increased transmigration of blood monocytes to AT.15,16 The same effect is seen with high-dose leptin and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1).5 Macrophage-derived TNF induces adipocyte lipolysis, which leads to release of free fatty acids from the adipocyte, which induces direct TLR4 signaling and NF-κB activation in macrophages.10 This paracrine loop involving inflammatory cytokines and free fatty acids establishes a vicious cycle between adipocytes and macrophages that propagates inflammation.17 Glucocorticoids and thiazolidinendiones have been shown to interfere with adipocyte mediated macrophage chemotaxis and recruitment.18 Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce the proinflammatory status of mature adipocytes by inhibiting basal release of MCP-1 and resistin.19

![]() AT also contains lymphocytes that contribute to AT inflammation.20 The AT T cells differ from those of other tissues and vary between different AT sites.20 The lymphocytes in epididymal AT are similar to those of the liver with predominant expression of “ancestral” innate immune system phenotype [natural killer (NK), γδ T] in up to 65%, whereas the adaptive phenotype (αβ T and B cells) predominates in blood, lymph nodes, and inguinal fat pads.20 Obesity causes site-specific changes in the proportions of these phenotypes.20 It has recently been shown that CD8+ T cells precede the accumulation of macrophages in AT, and in vitro coculture experiments have shown a vicious cycle of interaction between CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and AT, suggesting that AT activates CD8+ T cells, which in turn promote the recruitment and activation of macrophages.21

AT also contains lymphocytes that contribute to AT inflammation.20 The AT T cells differ from those of other tissues and vary between different AT sites.20 The lymphocytes in epididymal AT are similar to those of the liver with predominant expression of “ancestral” innate immune system phenotype [natural killer (NK), γδ T] in up to 65%, whereas the adaptive phenotype (αβ T and B cells) predominates in blood, lymph nodes, and inguinal fat pads.20 Obesity causes site-specific changes in the proportions of these phenotypes.20 It has recently been shown that CD8+ T cells precede the accumulation of macrophages in AT, and in vitro coculture experiments have shown a vicious cycle of interaction between CD8+ T cells, macrophages, and AT, suggesting that AT activates CD8+ T cells, which in turn promote the recruitment and activation of macrophages.21

![]() The interaction between adipocytes and lymphocytes was further explored when the inflammatory receptor CD40 was shown to be expressed on human adipocytes and to contribute to intercellular cross talk between adipocyte and lymphocyte.22 Lymphocyte adipocyte coculture showed upregulation of proinflammatory adipocytokines, including IL-6, MCP-1, and PAI-1, but downregulation of leptin and adiponectin.22 T lymphocytes were shown to regulate adipocytokine production, both through release of soluble factors and heterotypic contact with adipocytes involving the CD40/CD40 ligand (L) pathway.22

The interaction between adipocytes and lymphocytes was further explored when the inflammatory receptor CD40 was shown to be expressed on human adipocytes and to contribute to intercellular cross talk between adipocyte and lymphocyte.22 Lymphocyte adipocyte coculture showed upregulation of proinflammatory adipocytokines, including IL-6, MCP-1, and PAI-1, but downregulation of leptin and adiponectin.22 T lymphocytes were shown to regulate adipocytokine production, both through release of soluble factors and heterotypic contact with adipocytes involving the CD40/CD40 ligand (L) pathway.22

![]() Adipocytes also interact with blood vessels, and cross talk between perivascular AT and blood vessels has been demonstrated.23 Cross talk between AT and blood vessels is bidirectional, and dysfunction in either tissue influences the other.23 Perivascular AT secretes high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 compared to anti-inflammatory adiponectin, when compared to other AT depots.24

Adipocytes also interact with blood vessels, and cross talk between perivascular AT and blood vessels has been demonstrated.23 Cross talk between AT and blood vessels is bidirectional, and dysfunction in either tissue influences the other.23 Perivascular AT secretes high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 compared to anti-inflammatory adiponectin, when compared to other AT depots.24

Adipose Tissue Regional Differences

One of the characteristics of certain types of panniculitides is the preferential localization, such as the pretibial areas for EN, the calf for erythema induratum (EI), and the upper arms, shoulders, and face for lupus panniculitis. Location of panniculitis is a helpful adjunct for differential diagnosis of inflammation in AT and the question of why that occurs may be traced to the origin of the adipocyte regions from different areas of the mesoderm and the varying gene expression in different fat depots.25 The differences in gene expression between fat depots are large, up to 1,000-fold, and appear to be intrinsic, autonomous, and independent of the tissue microenvironment.25 Different AT depots may also contain variable percentage of adipocytes of different developmental origins,25 including brown AT (BAT) that has been observed to be present in white AT depots.25,26

The role of AT in innate immunity, inflammation, adaptive immunity, and energy homeostasis places the adipocyte itself centrally in the inflammatory disorders that affect it. The presence of adipocyte transmembrane PRRs, TLRs, and cytosolic PRRs, NLRs, and RLRs and receptors for interaction with macrophages and lymphocytes, as well as production and secretion of multiple cytokines and adipokines reflect the role of the adipocyte in protecting the host from infectious disease and other environmental dangers. The complex interweaving of the adipocyte’s role in such numerous and varied spheres may lead to complications should there be a genetic or acquired functional abnormality and/or molecular perturbations, and this may in some instances result in the inflammatory process known as panniculitis.

Nodular Lesions of the Legs

Nodular lesions of the legs may represent EN, EI, nodular vasculitis (NV), cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, or nodules related to vascular disorders. Diagnosis of these disorders often presents difficulties because their clinical manifestations as well as histopathological findings may overlap. In order to diagnose lesions of the leg, one needs information on the typical as well as unusual manifestations of each disorder, the associated diseases and conditions, and the histopathological presentation.

|

EN may occur in both genders, at any age from childhood to 70 years of age, but is more common in young women in the second to fourth decades of life.27 There is no gender difference in childhood cases. Prevalence varies from 2.4 per ten thousand population to 52 per million population, and in patient population from 0.38% to 0.5% of patients seen in clinics in Spain and England, respectively.28,29

EN is a panniculitis that has been reported in association with infections (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa), medications (antibiotics, oral contraceptives, halides), malignancies (most often leukemias or lymphomas), autoimmune diseases, and other inflammatory disorders, especially sarcoidosis and inflammatory bowel disease (see eTables 70-0.1 and 70-0.2). Geographical variations in infectious etiology occur, but streptococcal upper respiratory infections are the most common infectious etiologic factors and the most common causes in childhood.30 Tuberculosis was a common etiology in the past, and though less frequent now, must always be excluded. Half of all EN cases are idiopathic, without specific etiology, even though in many a viral cause may be suspected.30

Bacterial Infections

| Viral Infections

Fungal Infections

Protozoal infections

|

Drugs

Malignant Diseases

| Miscellaneous Conditions

|

EN is considered to be a hypersensitivity reaction to the various etiologic factors, but the pathophysiological mechanism of the disorder is not yet understood. Early studies have shown the presence of IFNγ and IL-2, activation of leukocytes, 31 and upregulation of various adhesion molecules,32,33 and genetic polymorphism in TNF-α promoter, MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor), or RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted).34–36 More recent information identifies AT as an immune organ and adipocytes as cells of the innate immune system, with primary responsibilities and capabilities of activating inflammatory systems and the adaptive immune system to destroy pathogens37 (see Section “Introduction”). Historically, the primary function of the adipocyte was thought to be protective. However, excessive adipocyte production and secretion of multiple proinflammatory adipokines and adipocytokines is associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes.37 In contrast, the inflammatory reaction of EN is associated with a more limited coccidiomycosis infection38 and with a less severe and shorter duration of sarcoidosis,38 especially in those carrying the HLA-DRB1*03-positive leukocyte antigen,39 which belongs to the “8.1 ancestral haplotype” genes associated with a wide range of immunopathologic diseases.40 Therefore, it is possible that, especially in AT, certain genetic mutations associated with enhanced inflammatory reactions may confer resistance to certain pathogens, and this may explain the observation that EN, whether in association with coccidiomycosis or sarcoidosis, may be protective against disease dissemination.38,39

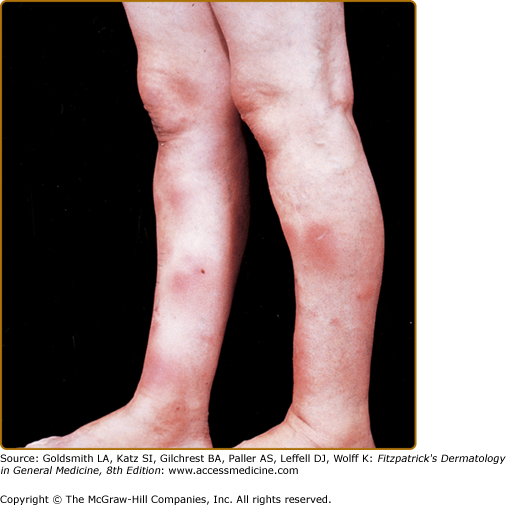

EN most commonly presents with an acute onset of tender, painful, erythematous, warm nodules and plaques on the anterior and at times the lateral aspect of both lower legs and ankles (Fig. 70-2). Other sites may also be involved, including forearms, thighs, and rarely the trunk or even the face, especially in children.41,42 The nodules may persist a few days or weeks, may become confluent, and evolve from an erythematous or purple-like hue to a bruise-like pigmentation called erythema contusiforme if hemorrhage is present in the AT. The eruption usually lasts from 3 to 6 weeks, with new lesions appearing for up to 6 weeks, but it may persist longer and may recur.42 The lesions do not ulcerate, and they resolve without atrophy or scarring.

Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, malaise, arthralgia, arthritis, and headache are common. Abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and cough are less frequent.30,42 Ocular manifestations may accompany the cutaneous lesions.42 Tonsillitis/pharyngitis/upper respiratory infection (URI) preceded the onset in 20%–30% in two series29,30 and prodromal symptoms may appear 1–3 weeks prior to lesional onset, at which time symptoms may become exacerbated.43

Laboratory abnormalities may include a high ESR, positive throat culture, or high ASO titer in those with a streptococcal etiology and leukocytosis. A positive PPD must be evaluated in the context of prevalence of tuberculosis in the geographical area. Chest X-ray will rule out pulmonary infectious or noninfectious disease (sarcoidosis), and serology or culture for various infectious diseases as well as other testing may be warranted in the appropriate setting (see eTables 70-0.1 and 70-0.2).

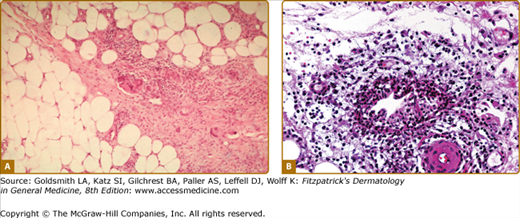

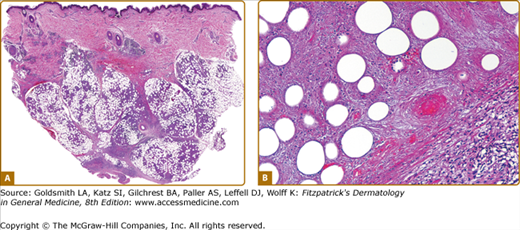

Histopathologically, EN is considered the prototype of septal panniculitis, although lobular inflammation may additionally be present. The composition of the inflammatory infiltrate varies according to lesional age, with the earliest lesions demonstrating septal edema, extravasated red blood cells, and scattered neutrophils. More fully developed lesions of EN show widening of the septa and early fibrosis, along with a septal infiltrate that includes lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.27,42,44 There may be extension of the infiltrate into adjacent fat lobules, but centrilobular necrosis of adipocytes is not seen.27,41,42 Late-stage lesions show widened and fibrotic septa, often containing granulomas (Fig. 70-3A). The fibrosis and inflammation may encroach upon and partially efface fat lobules. Occasionally, predominantly polymorphonuclear cells may be present in typical EN,45 but this is considered to be part of the early phase of inflammation.27,41,42

Miescher’s granuloma, a discrete micronodular aggregate of small histiocytes around a central stellate cleft27,42 (Fig. 70-3B), is considered characteristic of early EN by some, but is not universally found in EN,41,44 and has been described in other types of panniculitis.41 The picture of Miescher’s granuloma also evolves, as in later-stage lesions, some aggregates of larger histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells retain a central cleft. An overlying superficial and deep perivascular dermal infiltrate is frequently present in EN.41 Lipomembranous changes have been described in late stages of EN.27,42 Although by definition, vasculitis is characteristically absent in EN, thrombophlebitis has been emphasized by some as a feature in early EN,1 and medium vessel arteritis may rarely occur.4

Differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, infection-induced panniculitis, acute lipodermatosclerosis (LDS), EI/NV, which tends to appear on the calves and ulcerate, other vasculitides which must be differentiated histopathologically, and pancreatic panniculitis, which may occur anywhere on the leg, ulcerate and drain, and which is accompanied by an increase in serum lipase and amylase.

Treatment of EN primarily focuses on treatment or removal of the etiologic factor. Suspected medications should be discontinued, underlying infections sought and treated if possible, and associated inflammatory disorders or malignancies sought and appropriately treated. The disorder may persist for months before remission, and recurrence is possible, especially if the etiology is unknown.46 Additional management options include bed rest and leg elevation, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (avoided with IBD). Supersaturated potassium iodide solution (SSKI), 2–10 drops (1 drops = 0.03 mL = 30 mg) three times per day in water or orange juice has been useful, but individuals with thyroid disorders and on certain medications may be at risk for hypothyroidism and goiter as well as toxicity reactions of high potassium involving the heart and lungs.47 SSKI is contraindicated in pregnancy. Other medications that have been used to treat EN include colchicine (especially for Behcet’s disease),48 corticosteroids (rarely used, especially since an underlying infection must be ruled out), etanercept,49 and infliximab for IBD-associated EN.50

|

EI is an inflammatory panniculitis, most commonly presenting with ulcerated nodules on the calves, and frequently associated with MTB infection. A similar disorder, without ulceration appearing in calves and other lower extremity sites was subsequently described without MTB association and was called NV. However, with patients presenting with different features in either the same flare or in preceding or subsequent flares, multiple studies have concluded that the clinical and pathological features of the two nodular leg syndromes are so similar that it is impossible to separate them.51–54 Therefore, at this time the terms are most often used interchangeably. But some still prefer to use EI to denote the MTB-associated panniculitis, and NV for those without MTB association despite the otherwise identical features, to emphasize the need for antituberculosis therapy in the former cases.55

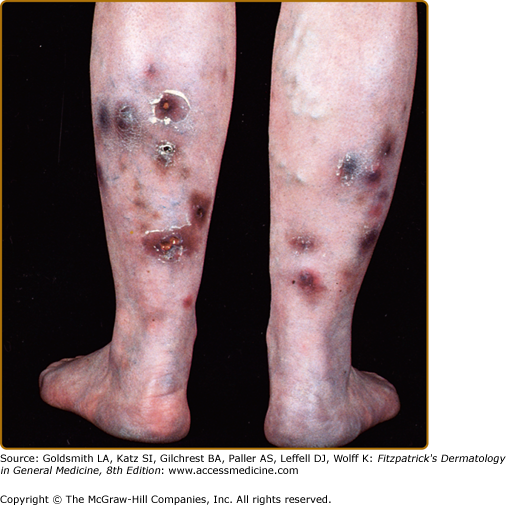

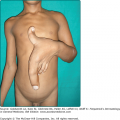

EI/NV is seen most commonly in young to middle-aged women, presenting as recurrent erythematous to violaceous nodules and deep plaques on the lower legs that may be tender, or only tender to pressure52 (Fig. 70-4). Some lesions may heal without scarring, but often ulceration leads to scarring.52 Surface changes include crusting of the ulcers and a surrounding collarette of scale (Fig. 70-5). The histology is shown in Fig. 70-6. The posterior leg calf region is the most frequent location, but lesions may also appear in the anterolateral areas of the legs, the feet, thighs, and rarely the arms and face.51 EI lesions develop more frequently during winter, and EI is commonly associated with obesity and venous insufficiency of varying degree and manifestation.52

![]() In the past, although EI was frequently associated with MTB, the etiology was still controversial since organisms were not always identified in the biopsies and tissue cultures of EI lesions. However, with the advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, multiple culture negative cases were shown to contain MTB DNA in involved tissue.56–58 Extracutaneous MTB is found in a significant numbers of EI patients, and may be present in lung, lymph nodes, kidney, or bowel.52 However, other infections or disorders have also been associated with EI/NV; these include hepatitis B, hepatitis C (Red finger syndrome and panniculitis), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and Nocardia infection.52,59–62 Medications, for example, propylthiouracil, have also been associated with EI/NV.63 In known endemic areas, fungal infections should be sought as possible etiological factors by stains, cultures, serology, and PCR, if strongly suspected.

In the past, although EI was frequently associated with MTB, the etiology was still controversial since organisms were not always identified in the biopsies and tissue cultures of EI lesions. However, with the advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, multiple culture negative cases were shown to contain MTB DNA in involved tissue.56–58 Extracutaneous MTB is found in a significant numbers of EI patients, and may be present in lung, lymph nodes, kidney, or bowel.52 However, other infections or disorders have also been associated with EI/NV; these include hepatitis B, hepatitis C (Red finger syndrome and panniculitis), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, and Nocardia infection.52,59–62 Medications, for example, propylthiouracil, have also been associated with EI/NV.63 In known endemic areas, fungal infections should be sought as possible etiological factors by stains, cultures, serology, and PCR, if strongly suspected.

![]() EI has been considered to be a hypersensitivity disorder mediated by immune complexes or cell-mediated hypersensitivity, as manifested by the presence of highly positive tuberculin skin tests, T lymphocyte hyperresponsiveness, and highly positive interferon-γ release assay tests to MBT.64–66

EI has been considered to be a hypersensitivity disorder mediated by immune complexes or cell-mediated hypersensitivity, as manifested by the presence of highly positive tuberculin skin tests, T lymphocyte hyperresponsiveness, and highly positive interferon-γ release assay tests to MBT.64–66

![]() The presence of MTB DNA in AT in the absence of positive bacterial cultures has pointed to AT as location for persistence of latent infections. In situ and conventional PCR techniques have shown that MTB DNA can be detected in AT s of various anatomic sites in patients who died from nontuberculosis etiologies and in perinodal AT of some patients who died with MTB.67 In vitro studies show that MTB can bind to scavenger receptors, enter adipocytes and, via the nearly 20 lipases of MBT, can appropriate the host lipids, accumulate intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions, and survive in a nonreplicating state that is insensitive to the major antimycobacterial medication isoniazid.67 However, rifampin and ethambutol can reduce MTB bacterial load in adipocytes by 80%–90%.67 Other organisms that can infect adipocytes and serve as a reservoir of recurrent reactivation include cytomegalovirus (CMV), Chlamydia pneumoniae, adenovirus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Rickettsia prowazekii, and Trypanosoma cruzi.68–71

The presence of MTB DNA in AT in the absence of positive bacterial cultures has pointed to AT as location for persistence of latent infections. In situ and conventional PCR techniques have shown that MTB DNA can be detected in AT s of various anatomic sites in patients who died from nontuberculosis etiologies and in perinodal AT of some patients who died with MTB.67 In vitro studies show that MTB can bind to scavenger receptors, enter adipocytes and, via the nearly 20 lipases of MBT, can appropriate the host lipids, accumulate intracytoplasmic lipid inclusions, and survive in a nonreplicating state that is insensitive to the major antimycobacterial medication isoniazid.67 However, rifampin and ethambutol can reduce MTB bacterial load in adipocytes by 80%–90%.67 Other organisms that can infect adipocytes and serve as a reservoir of recurrent reactivation include cytomegalovirus (CMV), Chlamydia pneumoniae, adenovirus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Rickettsia prowazekii, and Trypanosoma cruzi.68–71

![]() Adipocytes are cells of the innate immune system. Infection of adipocytes leads to activation of multiple signaling pathways, generating inflammatory responses to each threat with various cytokines and adipokines. These cytokines and adipokines bring other innate immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, NK cells) as well as adaptive immune cells (sensitized T cells) to the infection site that may help in containing infection. Why and how certain infections persist in spite of the inflammatory and immune response may vary with the organism involved as well as the host immune system. The location of the majority of EI/NV lesions in AT of the legs may be related to venous or lymphatic vessel insufficiency, or to different functional capacities of adipocytes in different locations.

Adipocytes are cells of the innate immune system. Infection of adipocytes leads to activation of multiple signaling pathways, generating inflammatory responses to each threat with various cytokines and adipokines. These cytokines and adipokines bring other innate immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, NK cells) as well as adaptive immune cells (sensitized T cells) to the infection site that may help in containing infection. Why and how certain infections persist in spite of the inflammatory and immune response may vary with the organism involved as well as the host immune system. The location of the majority of EI/NV lesions in AT of the legs may be related to venous or lymphatic vessel insufficiency, or to different functional capacities of adipocytes in different locations.

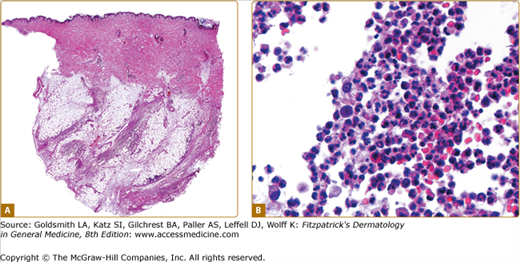

![]() Histopathological findings correlate with lesion duration, but the common denominator is a mostly lobular or mixed septal and lobular panniculitis (Fig. 70-6A). In early lesions, fat lobules contain discrete aggregates of inflammatory cells, with neutrophils predominating. Adipocyte necrosis is present to varying degree, leading to accumulations of foamy histiocytes. In established lesions of EI/NV, collections of epithelioid histiocytes, mutinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes produce a granulomatous appearance. Intense vascular damage, when present, is accompanied by extensive areas of caseous necrosis53,54 (Fig. 70-6B), eventuating in tuberculoid granuloma formation. The caseous necrosis may involve the overlying dermis to such an extent that ulceration occurs.53

Histopathological findings correlate with lesion duration, but the common denominator is a mostly lobular or mixed septal and lobular panniculitis (Fig. 70-6A). In early lesions, fat lobules contain discrete aggregates of inflammatory cells, with neutrophils predominating. Adipocyte necrosis is present to varying degree, leading to accumulations of foamy histiocytes. In established lesions of EI/NV, collections of epithelioid histiocytes, mutinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes produce a granulomatous appearance. Intense vascular damage, when present, is accompanied by extensive areas of caseous necrosis53,54 (Fig. 70-6B), eventuating in tuberculoid granuloma formation. The caseous necrosis may involve the overlying dermis to such an extent that ulceration occurs.53

![]() In a recent retrospective analysis by Segura et al52 of 101 biopsies in 86 patients with the clinicopathologic diagnosis of EI, vasculitis of some type was present in 90% of cases. The vessels involved were lobular venules, septal veins, and septal arteries. Given that even with meticulous examination and serial sectioning, vasculitis was not present in 10% of the biopsies, the authors concluded that vasculitis should not be considered a sine qua non requirement for histopathologic diagnosis of EI if otherwise consistent clinicopathologic features are present.

In a recent retrospective analysis by Segura et al52 of 101 biopsies in 86 patients with the clinicopathologic diagnosis of EI, vasculitis of some type was present in 90% of cases. The vessels involved were lobular venules, septal veins, and septal arteries. Given that even with meticulous examination and serial sectioning, vasculitis was not present in 10% of the biopsies, the authors concluded that vasculitis should not be considered a sine qua non requirement for histopathologic diagnosis of EI if otherwise consistent clinicopathologic features are present.

EI/NV can have a protracted course with recurrent episodes over years.52,53 Patients with EI/NV are for the most part in fairly good health, except for the associated diseases, without the symptoms usually associated with EN. There has been one case report of membranous glomerulonephritis associated with EI/NV72 and one case of painful peripheral neuropathy in an initially MTB skin test negative patient who was later found to have MTB-positive culture of cervical lymph node.73

In patients with positive MTB cultures, positive skin test or Quantiferon gold test for MTB, treatment with triple agent antituberculosis therapy is indicated. Patients with hepatitis B or C should receive appropriate intervention for that disorder. Other infectious etiologies including fungi, parasites, and viruses should be sought and treated, if present. Medications that may have incited EI should be discontinued.

Anti-inflammatory treatments that have been used in EI/NV not associated with MBT include super saturated potassium iodide (SSKI), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS), colchicine, antimalarials, corticosteroids,55 gold74 as well as bed rest or leg elevation, and treatment of venous insufficiency with compression and pentoxifylline. Other treatments that have been used include tetracycline and mycophenolate mofetil.75 If immunosuppressive agents are used, continued monitoring for possible infectious etiology is recommended.

Lipodermatosclerosis

|

LDS (synonyms: sclerosing panniculitis, hypodermitis sclerodermiformis, chronic panniculitis with lipomembranous changes, sclerotic atrophic cellulitis, venous stasis panniculitis) is a form of sclerosing panniculitis involving the lower legs.

LDS is the most common form of panniculitis, seen by clinicians far more frequently than EN, which has the next highest incidence. LDS occurs in association with venous insufficiency, mostly in overweight women over the age of 40.76,77 In a review of 97 patients with LDS, 87% were female with a mean age at diagnosis of 62 years; 85% of patients were overweight (BMI >30); and 66% were obese (BMI >34).78 Comorbidities included hypertension (41% of patients), thyroid disease (29%), diabetes mellitus (21%), prior history of lower extremity cellulitis (23%), deep vein thrombosis (19%), psychiatric illness (13%), peripheral neuropathy (8%), and atherosclerosis obliterans (5%).78 Due in part to its placement in the ICD9 classification under “Venous insufficiency with inflammation,” and its designation by various medical names (see list of synonyms for LDS above), precise data for prevalence of LDS are not available. With increasing rates of obesity in the United States and the aging of the baby boomer generation, a corresponding increase in incidence and prevalence of LDS will likely follow.

Most patients with LDS are female and also have in common venous hypertension and a higher than normal BMI. Additional associated features that have been sought as pathogenetic factors in LDS include the following: elevated hydrostatic pressure-induced increased vascular permeability secondary to downregulation of tight junctions79,80 with extravascular diffusion of fibrin78; microthrombi81; abnormalities in protein S and protein C82; hypoxia83; damage to endothelial cells by inflammatory cells84; upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), platelet- and endothelial-derived factors85; and inflammation with wound healing and local collagen stimulation leading to fibrosis and further vascular and lymphatic damage.78 The fibrosis is accompanied by increased transforming growth factor-β 1 (TGF-β1) gene and protein expression86 as well as an increase in procollagen type 1 gene expression.87

Hypoxia in AT induces chronic inflammation with macrophage infiltration and inflammatory cytokine expression.88 The adipocyte plays a significant role in extracellular tissue remodeling. For this task, the adipocyte produces multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) as well as tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) and other tissue proteases needed during tissue remodeling,89 all of which may significantly contribute to the tissue remodeling seen in LDS. Recent studies have linked expansion of AT (as seen in obesity) to resultant hypoxia, causing an increase in hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) expression.90 This stimulates multiple extracellular factors, including collagen I and III, as well as other components involved in remodeling the extracellular matrix, leading to fibrosis as the end result.91

A theory regarding an infectious pathogenesis of LDS was advocated by Cantwell and colleagues, who reported the presence of unusual acid-fast bacteria that could not be grown in culture in biopsies of several patients with LDS.92 This 1979 article dealt with the controversial issue of pleomorphic, nonrod-shaped, acid-fast bacteria being responsible for disease. It is widely accepted that other infections associated with repeated episodes of cellulitis cause lymphatic damage and subsequent changes in the AT.77 Particularly in the light of more recent discoveries that adipocytes are cells of the innate immune system and possible reservoirs of infectious organisms of all types, the role of infection as a contributing factor to LDS should be reconsidered and explored, perhaps in an analogous manner to that of the process leading to evidence of MTB DNA and dormant MTB in AT of the legs in EI.58,67

LDS has an acute inflammatory stage and a chronic fibrotic stage with a spectrum of intermediate77 and overlapping presentations. In patients presenting with the acute form (Fig. 70-7A), very painful, poorly demarcated, cellulitis-like erythematous plaques to purple somewhat edematous indurated plaques or nodules are seen on the lower legs, most commonly on the lower anteromedial calf area.77,93 Scaling may be present in some. The pain can be so intense that patients may not even tolerate a sheet while in bed. In this stage, patients are frequently diagnosed as having EN, cellulitis, or thrombophlebitis,77,93 and compression may not be tolerated. The acute form may last a few months or even a year.93 Although patients in this acute phase may present without obvious signs of venous disease,77 vascular studies show venous insufficiency in the majority.93 In the remaining group of LDS patients with normal venous studies, most have a high BMI, and given that obesity is usually associated with inactivity, these patients may not exert enough calf muscle contraction to maintain normal venous pressure in the lower extremities78; also, obesity is frequently associated with arterial hypertension.

The chronic form of LDS may or may not be preceded by a clinically obvious acute form.77 Chronic LDS features indurated to sclerotic, depressed, hyperpigmented skin (Fig. 70-7B). These findings occur on the lower portion of the lower leg, predominantly but not limited to the medial aspect, or in a stocking distribution. This is described as having an “inverted champagne bottle” or a “bowling pin” appearance.76,77,93

Although some patients may not describe associated pain or tenderness,93 pain is the most frequent symptom reported by others.78 Most of the patients are obese or overweight and have hypertension and evidence of venous abnormalities, but only rarely obstruction.78 Unilateral involvement is seen in 55%, localized plaque in 51%, and ulceration in 13% of cases78 (Fig. 70-8). Dermatosclerosis in patients with systemic sclerosis has been associated with pulmonary infarction and hypertension secondary to leg thrombi.94

Diagnostic tests to evaluate peripheral vascular disease should include ankle brachial index for arterial evaluation. Also indicated are venous tests: Dopplers to detect thrombi as well as color duplex sonography to detect direction of flow and presence of venous reflux.93 If the clinical findings are characteristic, biopsy of LDS is usually discouraged, due to the high incidence of subsequent development of ulcers at the biopsy site.77 But if necessary for diagnosis, a thin elliptical excision from the margin of an erythematous and indurated area, closed primarily with sutures, is recommended.77

Histopathologic findings reflect the evolution of the disease. Dermal stasis changes are present at any stage, and these include a variable degree of proliferation of capillaries and venules, small thick-walled blood vessels, extravasated erythrocytes, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, lymphohistiocytic inflammation, and fibrosis.53,95

In the subcutis, early lesions of LDS show a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes in the septa, accompanied by central lobular ischemic fat necrosis; the latter is recognized by the presence of pale-staining, small anucleate adipocytes. Capillary congestion is also observed within fat lobules; this may be accompanied by endothelial cell necrosis, thrombosis, red cell extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition.53,95 Septal fibrosis and small foci of lipomembranous fat necrosis and fat microcysts have also been described to occur in acute lesions.95 In lipomembranous or membranocystic change, small pseudocystic spaces are formed within necrotic fat. The spaces are lined by a hyaline eosinophilic material believed to be the residue of disintegrated adipocytes and their interaction with macrophages.96 This distinctive membranous lining is highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining and may present an arabesque pattern, with intricate undulating papillary and crenulated projections into the cystic spaces. However, membranocystic changes are not exclusive to LDS and may be found in any type of panniculitis.53,97

With progression of LDS, the spectrum of histopathologic changes encompasses increasing degrees of membranocystic fat necrosis, septal fibrosis, and thickening; an inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, histiocytes, and foamy macrophages; and partial to extensive atrophy of fat lobules.53,77,95 Advanced lesions show septal sclerosis most prominently, with marked atrophy of fat lobules secondary to lipophagic fat necrosis, accompanied by microcystic and lipomembranous change and a marked reduction in inflammation.53,95 The most severe LDS shows marked fibrosis and sclerosis in the AT layer with little inflammation.77 In late stages, with fibrous thickening of the lower dermis and replacement of the subcutis by sclerosis, a punch biopsy of involved skin may not produce any subcutaneous fat.98

Compression therapy is the major universally recommended treatment for LDS.77,78 Higher compression gradient (30–40 mm Hg) may be more effective, but lower class compression (15–20 mm Hg or 20–30 mm Hg) may be associated with higher rate of compliance, especially in the elderly, and has been shown to be effective in decreasing edema.99 One mechanism by which compression improves venous return and decreases edema is via tightening of vascular tight junctions, significantly elevating expression of tight junction proteins and inhibiting permeability of fluid into the perivascular tissue, thereby preventing progression of venous insufficiency.79,80 Stockings must be worn all day and not removed until bedtime, since even a few days without compression may lead to recurrence of the edema and inflammation.99

Stanazolol has been shown to be effective in LDS, with decrease in pain, erythema, and induration.77,100 Patients tolerated the treatment well, but potential side effects of this treatment include hepatotoxicity, and this may preclude its widespread use. In the United States, this drug is no longer distributed. Other anabolic steroids such as oxandrolone and danazol have also been used.101,102 Pentoxifylline has been successfully used in LDS cases with and without associated ulceration. A Cochrane Database System review of 12 trials involving 864 patients in 2007 concluded the drug was a useful adjunct to compression for treating venous ulcers and may be effective in the absence of compression.103 Other treatments for chronic venous insufficiency include horse chestnut seed extract,104,105 oxerutin,106,107 and flavonoid fraction.108

Ultrasound therapy was reported in two studies as being successful in reducing and even resolving hardness, tenderness, and erythema.109,110 Readily available through physical therapy departments, it is a simple and safe treatment of a painful and refractory condition and may be used along with Grade-2 compression therapy.109,110

Infection-Induced Panniculitis

|

Infection-induced panniculitis (Infectious panniculitis, infective panniculitis) is panniculitis directly caused by an infectious agent.62 AT infection can be due to bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses.53,62,111 Primary infections produced by direct inoculation at a wound site (injury, surgical procedure, catheter, injection, acupuncture) usually result in a single lesion which may enlarge and spread locally.53,62,111 Secondary infections caused by sepsis and hematogenous spread may manifest as single or multiple lesions.53,62,111 In immunosuppressed patients, microorganisms may be numerous and identified on routine histopathology or special stains. In immunocompetent patients, microorganisms may be sparse and not seen on either routine histopathology or special stains, requiring positive cultures or serological studies for identification.53,62,111 Recent reports of infectious etiologies in association with various autoimmune disorders include Staphylococcus aureus panniculitis with juvenile dermatomyositis (DM),112 Mycobacterium- and Histoplasma-associated panniculitis with rheumatoid arthritis,113,114 and diffuse fusariosis with acute lymphobastic leukemia (ALL).115

![]() Nowhere is an understanding of adipocyte function more important than in appreciating its role in infectious diseases. As noted in the introduction, the adipocyte is an innate immune cell, equipped with surface, transmembrane, and cytosolic PRRs to deal with and defend against various microbes. Once TLRs and NLRs are activated, multiple immune response genes participate. These induce the adipocyte to produce various cytokines, chemokines, and adipokines, thus promoting adaptive immune responses and allowing the full spectrum of the inflammatory and immune system to target the site of infection. It appears that the innate immune system tailors specific and distinct TLR- and NLR-mediated transcriptional responses to the various individual microbial infections.116 With recognition of the evolution of a significant immune defense function of the adipocyte, it should come as no surprise that organisms of all types infect AT, and an important reason for microbial persistence within AT is the strategic abilities of organisms to circumvent immune response signaling and to utilize the intracellular environment to evade the immune system.117

Nowhere is an understanding of adipocyte function more important than in appreciating its role in infectious diseases. As noted in the introduction, the adipocyte is an innate immune cell, equipped with surface, transmembrane, and cytosolic PRRs to deal with and defend against various microbes. Once TLRs and NLRs are activated, multiple immune response genes participate. These induce the adipocyte to produce various cytokines, chemokines, and adipokines, thus promoting adaptive immune responses and allowing the full spectrum of the inflammatory and immune system to target the site of infection. It appears that the innate immune system tailors specific and distinct TLR- and NLR-mediated transcriptional responses to the various individual microbial infections.116 With recognition of the evolution of a significant immune defense function of the adipocyte, it should come as no surprise that organisms of all types infect AT, and an important reason for microbial persistence within AT is the strategic abilities of organisms to circumvent immune response signaling and to utilize the intracellular environment to evade the immune system.117

![]() Adipocytes can be infected in vitro with all types of organisms, including Chlamydia pneumonia, CMV, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza,68 MTB,67 Rickettsia prowazekii,69 Trypanosoma cruzi,70,71,118 Coxiella burnetii,69 and HIV.119,120 In vitro infection of adipocytes with T. cruzi results in increased expression of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, IFNγ, TNFα, CCL2, CCL5, CXCL10, an increase in TLR2 and TLR9 and acute phase reactants α1 acid glycoprotein and serum amyloid A3 (SAA3), but a decrease in adiponectin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), the negative regulators of inflammation.71,121 T. cruzi infects and replicates within adipocytes both in vivo and in vitro, as adipocytes are important targets of this parasite.121 Real time PCR has shown that at 300 days postinfection a comparable number of parasites are present in both AT and heart tissue, indicating that AT is a reservoir for the parasites.70,121 AT may serve as a reservoir for Rickettsia prowazekii and MTB.67,69,70 MTB has been shown to be present in AT by PCR in EI, 56–58,122 and as noted in Section “Erythema Induratum”, once MTB organisms enter adipocytes, they appropriate host lipids and survive in a nonreplicating state, insensitive to isoniazid but sensitive to rifampin and ethambutol.67 One hypothesis is that access of mycobacteria to O2 is limited in adipocytes, inducing mycobacterial dormancy. Subsequent to resumption of bacillary growth, bacilli may then serve as a source for extrapulmonary TB, which accounts for 15% of total TB reactivation cases.67

Adipocytes can be infected in vitro with all types of organisms, including Chlamydia pneumonia, CMV, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza,68 MTB,67 Rickettsia prowazekii,69 Trypanosoma cruzi,70,71,118 Coxiella burnetii,69 and HIV.119,120 In vitro infection of adipocytes with T. cruzi results in increased expression of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, IFNγ, TNFα, CCL2, CCL5, CXCL10, an increase in TLR2 and TLR9 and acute phase reactants α1 acid glycoprotein and serum amyloid A3 (SAA3), but a decrease in adiponectin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), the negative regulators of inflammation.71,121 T. cruzi infects and replicates within adipocytes both in vivo and in vitro, as adipocytes are important targets of this parasite.121 Real time PCR has shown that at 300 days postinfection a comparable number of parasites are present in both AT and heart tissue, indicating that AT is a reservoir for the parasites.70,121 AT may serve as a reservoir for Rickettsia prowazekii and MTB.67,69,70 MTB has been shown to be present in AT by PCR in EI, 56–58,122 and as noted in Section “Erythema Induratum”, once MTB organisms enter adipocytes, they appropriate host lipids and survive in a nonreplicating state, insensitive to isoniazid but sensitive to rifampin and ethambutol.67 One hypothesis is that access of mycobacteria to O2 is limited in adipocytes, inducing mycobacterial dormancy. Subsequent to resumption of bacillary growth, bacilli may then serve as a source for extrapulmonary TB, which accounts for 15% of total TB reactivation cases.67

![]() Studies to date indicate that Mycobacterium leprae has very limited growth potential in AT. Murine preadipocytes can be infected in vitro with M. leprae and bacilli counts can be maintained during adipocyte differentiation for 3 months using a three-dimensional in vitro cultural system reconstituting dermis,123,124; however, when the infected adipose nodules were injected into nude mice, and incubated in vivo for 3 months, bacilli counts showed no increase, indicating that preadipocytes and mature adipocytes were not permissive for M. leprae multiplication and logarithmic growth.124 By virtue of their high expression of TLR4, adipocytes are highly responsive to endotoxin, producing proinflammatory cytokines at comparable or higher levels than macrophages.121 TLR2 induction in adipocytes confers a high degree of sensitivity to fungal cell-wall components.121 Liposaccharide (LPS) injection in the absence of adipocytes in a murine lipodystrophy model lead to a marked decrease in systemic IL-6 and SAA3 levels.121 IL-6 is secreted by adipocytes into the circulation, and a significant fraction of circulating IL-6 is AT-derived, playing an important role in host defense mechanism at times of infections.121 The increase in inflammatory cytokines from AT is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity, increased lipolysis, increase in leptin and decrease in adiponectin, contributing to metabolic alterations.121 Mutations coding TLRs or downstream signaling proteins increase infections.125 Point mutations in TLR2 have been associated with higher risks of lepromatous than tuberculoid leprosy.126 TLR4 mutations have been described that decrease responsiveness to LPS.125,127 Stem cell transplants from donors with the hyporesponsive TLR4 variant induced greater susceptibility to aspergillosis in the immunosuppressed recipients.125,128 The genetic variants in TLRs and other innate immune signals and their effect on adipocyte function and development of panniculitis is not yet known.

Studies to date indicate that Mycobacterium leprae has very limited growth potential in AT. Murine preadipocytes can be infected in vitro with M. leprae and bacilli counts can be maintained during adipocyte differentiation for 3 months using a three-dimensional in vitro cultural system reconstituting dermis,123,124; however, when the infected adipose nodules were injected into nude mice, and incubated in vivo for 3 months, bacilli counts showed no increase, indicating that preadipocytes and mature adipocytes were not permissive for M. leprae multiplication and logarithmic growth.124 By virtue of their high expression of TLR4, adipocytes are highly responsive to endotoxin, producing proinflammatory cytokines at comparable or higher levels than macrophages.121 TLR2 induction in adipocytes confers a high degree of sensitivity to fungal cell-wall components.121 Liposaccharide (LPS) injection in the absence of adipocytes in a murine lipodystrophy model lead to a marked decrease in systemic IL-6 and SAA3 levels.121 IL-6 is secreted by adipocytes into the circulation, and a significant fraction of circulating IL-6 is AT-derived, playing an important role in host defense mechanism at times of infections.121 The increase in inflammatory cytokines from AT is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity, increased lipolysis, increase in leptin and decrease in adiponectin, contributing to metabolic alterations.121 Mutations coding TLRs or downstream signaling proteins increase infections.125 Point mutations in TLR2 have been associated with higher risks of lepromatous than tuberculoid leprosy.126 TLR4 mutations have been described that decrease responsiveness to LPS.125,127 Stem cell transplants from donors with the hyporesponsive TLR4 variant induced greater susceptibility to aspergillosis in the immunosuppressed recipients.125,128 The genetic variants in TLRs and other innate immune signals and their effect on adipocyte function and development of panniculitis is not yet known.

The clinical appearance of infectious panniculitis varies from fluctuant- or abscess-type lesions with purulent discharge and ulcerations to nonspecific erythematous firm nonfluctuant subcutaneous plaques and nodules, purpuric plaques, and EN-type lesions.62,111,129 Deep nodules or plaques may not always appear fluctuant, and pustules, fluctuant papules, and ulcers can be superimposed on top of the nodules.111 The most common sites of infection are the legs and feet, but upper extremities, trunk, and face may also be involved.62,111 Immunosuppression of varying etiology is the most frequent, but not universal, association.53,62,111 Immunosuppression is associated with more widespread abscess-type lesions containing nontuberculous mycobacteria, whereas in immunocompetent patients, granulomas are more commonly seen.111,130 Fungal infections occur in the following clinical settings: (1) localized environmentally injected panniculitis of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sprorotrichosis; or (2) panniculitis associated with systemic disseminated fungal infection that may be seen in individuals with normal immune functions, or with opportunistic fungal infection seen in immune compromised individuals.111,129 Clinical features vary with the setting, the infective organism and the underlying state of the individual’s immunocompetence or immunosuppression.111,129

Evaluation of panniculitis for infections should include histopathologic studies with special stains for all types of organisms as well as culture and sensitivity testing of biopsy material. In the immunosuppressed patient, microorganisms may be numerous and more readily identified, but in immunocompetent patients, microorganisms may not be seen on either routine histopathology or special stains, requiring positive cultures or serological studies for identification.53,62,111 The anti-Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) polyclonal antibody immunostain cross-reacts with many bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi with minimal background staining and is advocated as a good screening tool for detection of microorganisms in paraffin-embedded tissue specimens when conventional stains are negative.53,111,131 Molecular PCR techniques have been utilized with mycobacterium infections.56–58,122 Histopathologic features may vary with the organism and its virulence, the host immune status, and the duration of the lesion at time of biopsy.62 Classified by some as a mostly lobular panniculitis,53 infection-induced panniculitis often presents a mixed septal and lobular pattern, and a predominantly septal, EN-like neutrophilic panniculitis has also been reported to occur in cases of bacterial as well as fungal etiology.62 The superficial dermis is the epicenter of inflammation in infections acquired by direct inoculation or by an indwelling catheter, in contrast to more deeply seated infections secondary to hematogenous spread involving the deep reticular dermis and subcutaneous fat.53

Generally, in a typical case, the subcutaneous fat contains a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and some admixed lymphocytes and macrophages, often with extension into the overlying dermis and with abscess formation a common finding.62,111 Patterson et al additionally noted distinctive subcutaneous features in the majority of 15 reported cases of infection-induced panniculitis of bacterial, atypical mycobacterial and fungal origin, independent of the particular causative microorganism. These features included hemorrhage, vascular proliferation, foci of basophilic necrosis, and sweat gland necrosis. Overlying changes such as parakeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis were seen in all cases in which the epidermis was available for examination. All 15 cases also had dermal findings, most commonly upper dermal edema, a diffuse and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, often with prominent neutrophils, proliferation of thick-walled vessels, and focal or diffuse hemorrhage.62 With observation of any of these enumerated features, special stains for bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi are imperative, and additional immunohistochemistry or PCR amplification techniques may be necessary.

Other histopathologic changes may point toward a more particular etiology. Suppurative granulomas formed by epithelioid histiocytes surrounding aggregated neutrophils may occur in panniculitis caused by atypical mycobacteria.53 Caseating granulomas, though rarely seen, raise suspicion for tuberculous panniculitis.111 A case of panniculitis secondary to CMV has been reported as a mostly septal panniculitis with many CMV inclusions contained within endothelial cells.132

Differential diagnosis includes α1-antitrypsin (α1AT) panniculitis, pancreatic panniculitis, traumatic, and factitial panniculitis. It is important to recall that presence of one of the above diagnostic types of panniculitis does not exclude infection, as in the case of α1AT panniculitis associated with lymph node histoplasmosis.133

Treatment will vary and depend on the suspected or known organisms and their cultures and sensitivities. In cases involving bacteria such as MTB and parasites such as T. cruzi, their known capability to remain dormant in AT necessitates the use, for adequate treatment durations, of appropriate antibiotics, selected for their abilities to affect nonreplicating organisms.67,121

α1-Antitrypsin Panniculitis

- Clinical

- ZZ-, MZ-, MS-, and SS-phenotype-associated panniculitis rare, with higher percentage (>60%) in ZZ cases; low levels of α1-antitrypsin are associated with emphysema, hepatitis, cirrhosis, vasculitis, and angioedema.

- Subcutaneous nodules mostly located on the lower abdomen, buttocks, and proximal extremities.

- Frequent ulceration and isomorphic phenomenon.

- ZZ-, MZ-, MS-, and SS-phenotype-associated panniculitis rare, with higher percentage (>60%) in ZZ cases; low levels of α1-antitrypsin are associated with emphysema, hepatitis, cirrhosis, vasculitis, and angioedema.

- Histopathology

- Mostly lobular panniculitis without vasculitis.

- Necrosis of fat lobules with a dense inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils.

- Splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles of deep reticular dermis.

- Large areas of normal fat adjacent to necrotic adipocytes.

- Mostly lobular panniculitis without vasculitis.

- Treatment

- Dapsone, doxycycline.

- Homozygous ZZ patients with severe forms of the disease: supplemental intravenous infusion of exogenous α1-proteinase inhibitor concentrate or α1-antitrypsin produced by genetic engineering; liver transplantation.

- Dapsone, doxycycline.

α1AT is a glycoprotein that accounts for 90% of the total serum serine protease inhibitor capacity in humans.134 It is produced and secreted mainly by hepatocytes, but also in small amounts by monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils,135–137 and is known to inhibit trypsin, chymotrypsin, leukocyte elastase, kallikrein, collagenase, plasmin, and thrombin among other proteases.134 α1AT may also help regulate protease stimulated activation of lymphocytes, phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils, and complement activation.138–141 It is an acute phase reactant, increased in times of stress.

α1AT deficiency is inherited as a codominant disorder, and more than 100 alleles have been identified.142,143 The α1AT phenotypes are classified according to gel electrophoresis migration/mobility as F (fast), M (medium), S (slow), and Z (very slow), but null variants that do not produce any α1AT and patients may have dysfunctional α1AT with normal levels.144 Homozygous MM, the most common phenotype, is associated with normal levels of α1AT, whereas those homozygous for ZZ have low levels at 10%–15% of normal, and those heterozygous for S or Z allele have levels in between. MS heterozygous individuals may have low normal serum levels.145 Due to the complex nature of these proteins, combination protein levels, or phenotyping and genotyping, have been recommended.144 Estimated prevalence of α1AT deficiency in Caucasians is 1 per 3,000–5,000 in the United States, with incidence in Caucasian newborns similar to that of cystic fibrosis.144

α1AT deficiency is most commonly associated with pulmonary and hepatic disease, leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hepatic cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma144; the ZZ genotype is at highest risk. There is no association of the null variant with hepatic disease, as it is the accumulation of polymerized α1AT in the liver that induces damage, and accumulation does not occur in this variant.144 The exact mechanism of injury is still controversial.144

Panniculitis uncommonly occurs in α1AT deficiency. Less than 50 cases have been reported146,147 in ZZ, MZ, MS, and SS phenotypes, with higher percentage (>60%) of ZZ cases as well as higher incidence in women (65%).146 Presenting in an age range from childhood (infancy) to the elderly, panniculitis is most frequently seen between ages 30 and 60.146,148 Patients present with painful erythematous nodules and plaques, but early lesions may have a cellulitic or fluctuant abscess-type appearance (Fig. 70-9A). Lesions may ulcerate and discharge an oily material or serosanguineous discharge9 (Fig. 70-9B) and resolve with atrophic scars.53 The lesions appear most commonly on the lower trunk (buttocks) (Fig. 70-10) and proximal extremities, but lower legs and other sites may be affected.53,146,150 As trauma or excessive activity may precede the onset of lesions in a third of patients,53,146 debridement is discouraged.53 α1AT panniculitis has occurred in patients with such conditions as hypothyroidism, mixed connective tissue disease, lymphoproliferative disorders, and infections, including a focus of histoplasmosis in a lymph node.133,149 Therefore, the presence of α1AT deficiency in association with panniculitis should not preclude a search for infection or other underlying medical problems such as autoimmune disorders, malignancies, or infections, since they may coexist. Cutaneous and subcutaneous necrosis can develop rapidly. Extensive involvement with α1AT panniculitis can be life threatening, and fatal cases have been reported.148,151,152 Erythrophagocytosis was noted in the biopsy of one of the patients with fatal panniculitis.153

Possible mechanisms leading to the development of α1AT panniculitis include lack of interference with the various proteases that lead to activation of lymphocytes, macrophages, complement, and lysis and destruction of connective tissue at sites of inflammation. Trauma to adipocytes may result in their activation, with release of the various adipokines and cytokines that are chemotactic to inflammatory cells, whose released proteases are unopposed due to absence of the α1AT, leading to severe damage in involved tissue.154,155 Animal models of soft tissue injury show elevated levels of IL-6 and MCP-1 and increased systemic inflammatory mediators.154

Histopathologic findings vary with the age and type of lesion biopsied. Early in their development, nodular lesions may reveal edema and degeneration of adipocytes, with ruptured and collapsed cell membranes and a perivascular mononuclear infiltrate.153 Also reported at this stage is a mild infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages in septa and lobules, with foci of early necrosis of subcutaneous fat. This may be accompanied by splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles throughout the overlying reticular dermis, considered an early and distinctive diagnostic clue.156 More advanced lesions have masses of neutrophils and histiocytes associated with necrosis and replacement of fat lobules (Figs. 70-11A and 70-11B). A focal pattern of involvement is another distinguishing feature that may be appreciated, manifested by large areas of normal fat in immediate proximity to necrotic septa and fat lobules.157 Liquefactive necrosis and dissolution of dermal collagen may be accompanied by ulceration, and degeneration of elastic tissue may lead to septal destruction and the appearance of “floating” necrotic fat lobules.149,158 A rare occurrence is an exclusively septal pattern of mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of neutrophils.146,158 Neutrophils and necrotic adipocytes are less prevalent in late stage lesions, with replacement by lymphocytes, foamy histiocytes, and variable amount of fibrosis within fat lobules.149,159