Osseous Genioplasty

Harvey M. Rosen

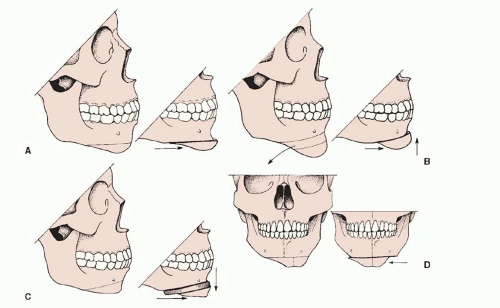

Osseous genioplasty is an autogenous method for changing the size, or shape, or both of the mandibular symphysis. Although by strict definition it may involve merely recontouring the chin by burring away bone or by adding bone graft material, the term generally refers to an osteotomy of the anterior mandible in the horizontal (transverse) direction below the mental foramina (Figure 51.1A). The osteotomy was first described in 1942 by Hofer.1 The procedure remained rather obscure until 1964 when it was popularized by Converse and Wood-Smith.2 It is now the second most commonly performed osteotomy of the facial skeleton for both reconstructive and aesthetic reasons (second only to rhinoplasty).

Osseous genioplasty is frequently performed for two reasons: (a) versatility, the chin can be moved in any direction—sagittally, vertically, or transversely (Figure 51.1 B-D); and (b) a receding chin or small mandible, or both, are common problems among white North Americans, occurring in approximately 5% of the population.3 When these factors are coupled with the emphasis that Western culture places on aesthetics and the belief that a well-defined jaw line characterizes an aggressive, self-confident individual, it is little wonder that this operation has grown in popularity. The ready availability of alloplastic material such as silastic, however, has prevented osseous genioplasty from becoming an operation that large numbers of plastic surgeons currently employ.

ALLOPLASTIC VERSUS AUTOGENOUS

The choice between alloplastic augmentation (chin implants) and osseous genioplasty for correction of the weak chin remains controversial. The proponents of alloplastic augmentation cite the technical ease, the relatively low risk of complications, and the ability to perform the procedure under a local anesthetic. Those who favor osseous genioplasty point out the extreme versatility of an osteotomy in correcting three-dimensional deformity.

In an effort to select the correct procedure, one should simply ask which procedure will provide the best correction for the particular patient. Certain factors are indisputable: (1) Chin implants can adequately correct mild to moderate volume deficiencies of the mandible at the level of the pogonion in the sagittal dimension. (2) Chin implants cannot correct vertical excess of the anterior mandible. (3) Chin implants are unreliable in correcting asymmetries of the anterior mandible in any plane of space. (4) Although chin implants can modestly increase the vertical dimension of the anterior mandible by covering its inferior border, this has significant potential for complications as the soft tissue in this area is relatively thin. (5) Provided that chin implants are positioned directly over the symphysis, as they should be, and not over the dental alveolus, the labiomental fold will increase in depth following chin implant placement.

Given these factors, the only appropriate candidates for chin implantation are those with a mild to moderate sagittal deficiency of the chin accompanied by a shallow labiomental fold. All other patients who request surgical alteration of the chin should be considered for osseous genioplasty.

One of the least mentioned, yet compelling, reasons to choose osseous genioplasty instead of alloplastic chin augmentation occurs when surgical revision is indicated. Osseous genioplasty is more amenable to revision because the soft-tissue chin has not been degloved and there is no scar capsule (as occurs in smooth implants) with which to contend. As a result, soft-tissue displacement closely follows skeletal displacement. Conversely, the soft-tissue response to removing a smooth implant, or to reducing its size, or to changing its position is unpredictable because the soft tissues have been degloved from the bone. In addition, the dead space created by the implant capsule, which does not fully collapse, fills with blood, creating more scar. Surgical excision of the capsule may cause mentalis muscle dysfunction with subsequent lower lip ptosis. Accordingly, the aesthetic consequences of removing or changing smooth chin implants are frequently undesirable.

Although a scar capsule may not form with porous implants, these implants can be very difficult to remove because of the soft-tissue ingrowth.

TREATMENT-PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS

Preoperative evaluation of the osseous genioplasty patient includes a history and physical examination. The surgeon should ascertain the patient’s specific aesthetic complaints and objectives as they relate to the lower face, including any concerns about the height, the projection, and the symmetry in this area. Specific inquiries should be made into any history of orthodontic therapy, because such therapy may have been used to disguise an underlying class II malocclusion caused by a small mandible.

Physical examination should note the following five items:

The sagittal position of the pogonion relative to the lower lip and the remainder of the mid- and upper face. The lower lip, not the mid- or upper facial structures, determines the extent to which the chin should be brought forward.4 Consequently, the chin should not be brought forward any further than a vertical line dropped from the lower lip. When advancing the chin, the ratio of soft tissue to skeletal displacement is generally 1:1. If the lower lip is recessive, as it may be in many individuals with small mandibles who are seeking chin enlargement, one must be willing to accept a residual degree of sagittal weakness of the lower face relative to the mid- and upper face. This is aesthetically preferable to a chin that is advanced beyond the lower lip, which invariably results in a bizarre, artificial appearance. Undercorrection in the sagittal dimension is always preferable to overcorrection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree