PRACTICES FOR HEALTH AND BEAUTY

By

Caren M. Barnes

Professor Coordinator of Clinical Research

University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Dentistry

Chi Shing Wong

Member, Product Development Group

Colgate-Palmolive Global Toothbrush Division

James G Masters, Ph.D.

Director in the Research and Development Division

Colgate-Palmolive Company

Shira Pilch, Ph.D.

Associate Director: Research and Development Division

Colgate-Palmolive Company

Michael Prencipe, Ph.D.

Director in the Research and Development Division

Colgate-Palmolive Company

ABSTRACT

The desire to have a beautiful smile with glistening white teeth is a universal aspiration, as important to the aesthetic sense as having a youthful, wrinkle-free skin or a beautifully sculpted body. This article highlights the importance of this area to both the dental profession and the consumer, and discusses the growing demand for aesthetic dental procedures.

Having a beautiful smile involves more than brushing one’s teeth twice a day. For generations, the mouth was not considered to have an effect on total body health, nor was the mouth considered to reflect total body health. The relationship of total body health and oral health is explained in this chapter. However, it is clear that total body health includes having a state of oral health. Current issues around oral health are also discussed, such as the effects of aging on oral health.

This chapter contains scientific, evidence-based information on daily oral health regimes that are thorough and effective, including proper brushing, cleaning between teeth, and techniques for resolving halitosis. The key to a healthy mouth is the thorough, daily removal of dental plaque biofilm that must be performed mechanically, whether with a manual or powered toothbrush and with some method of removing the dental plaque biofilm from the surfaces of the tongue and between the teeth.

The chapter contains detailed information (i.e., ingredients, design) about oral hygiene products necessary for achieving and maintaining oral health. The oral hygiene products encompassed are toothpastes, mouthrinses, manual and powered toothbrushes, and waterflossers (Waterpik) as well as products for cleaning surfaces between the teeth and the ingredients that make them effective for specific oral problems, such as inflamed gums (gingivitis), cavities (dental caries), removal of dental stains and/or whitening teeth, and treatment of hypersensitivity.

A. Important Issues in Oral Health

B. Importance of Aesthetics in Dentistry

D. Oral Issues Related to Aging

1. Demographics of Aging: What to Expect

1. Regulation (Therapeutic vs. Cosmetic Benefits)

6. Non-Therapeutic Ingredients for Cosmetic Benefits

2. Importance of Toothbrush Features

2. Types of Powered Toothbrushes

C. Interdental Cleaning Devices

1. Importance of Interdental Cleaning

2. Dental Floss—The Shortcomings

4. Additional Interdental Cleaning Aids

A. Important Issues in Oral Health

Dental Plaque Biofilm

The role of dental plaque biofilm has been recognized for decades as being the agent responsible for dental caries and periodontal disease. Through ongoing research it is now recognized that dental plaque biofilm has a potential, if not definitive role, in the link between systemic and oral diseases. Dental plaque biofilm consists of over 500 species of bacteria that live in a well-organized bacterial community and are embedded in an extracellular slime layer that adheres to the surface of teeth and soft oral tissues. The links between dental plaque biofilm and systemic disease are related to the magnitude of the number of bacteria that reside in dental plaque biofilm as well as the inflammatory conditions they set up in the oral cavity and become involved with other parts of the body and thus, systemic disease. Research on the links between systemic and oral diseases have been and continue to be heavily researched.

Dental Caries

The past 50 years have seen a shift in what has previously been considered “oral” health. The shift has been from a focus on teeth and gingiva to the

realization, by multiple healthcare professions, that the mouth is a mirror of the state of health or disease in individuals.1 Great strides have been made in the past fifty years in the reduction of the prevalence of dental caries, although this is clearly still a significant public health issue. Clearly, fluoride is effective when delivered from toothpaste and incorporated in drinking water. By this means dental caries rates have decreased 30–50%.2 Fluoridated water supplies in the U.S. have saved more than $4.6 billion annually in dental costs.2 On a community level, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported that for every dollar spent on water fluoridation, $7.00–$42.00 is saved in oral health treatment costs, depending on the size of the community.2 Assessments to determine risk for dental caries are being utilized (Caries Assessment and Management By Risk Assessment: CAMBRA), and notably there have been advancements in dental caries detection devices, particularly with the use of digital radiographs, quantitative light fluorescence, and fiber optic trans-illumination along with other new caries detection devices.3 For over a decade we have had the scientific evidence that dental sealants do work, particularly those applied to children in school programs.4 In addition, fluoride varnishes are playing an ever-increasing major role in the fight against cavities due to their proven efficacy and ease of application at the dentist office.

Periodontal Disease

The success for preventing periodontal disease has not been as effective as it has for dental caries. The results of a major study, Prevalence of Periodontitis in Adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010 estimates that 47.2%, or 64.7 million American adults, have some form of periodontal disease. Gingivitis, an inflammation of the gingiva, can be reversed; periodontitis cannot. If gingivitis is left untreated, inflammation can progress from the gingiva and will begin to affect the supporting structures of the teeth. The bone that supports the tooth in the affected socket(s) will be destroyed as well as the fibers that connect the root of the teeth to the bone.

Periodontal disease can be stopped most times with appropriate professional treatment and diligent homecare by the patient but the destruction, for the most part, cannot be reversed. Periodontal disease can be mild, moderate or severe, is a cumulative disease and, in adults 65 and older, its prevalence rate (evidence of having had period at some point in their lives) increases to 70.1 percent as described in a study published in the Journal of Dental Research, the official publication of the International and American Associations for Dental Research.

Currently there is ongoing research on oral changes that occur due to systemic diseases, access to oral care initiatives, and studies of the effects of aging on the oral cavity. There is no doubt at this time that a focus will remain on prevention and treatment of dental caries and periodontal disease.5 It is also strongly believed there will continue to be research on oral cancer and the links between systemic diseases such as diabetes and the state of health or disease of the oral cavity as well as the effect that they have upon each other. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Oral Health Program is currently developing new Strategic Planning for 2015 and several years beyond. Notably, some of their priority areas in their strategic planning include, but are not limited to study of: dental caries, periodontal diseases, oral and pharyngeal (mouth and throat) cancers, infection control, and elimination of health disparities.

In addition to dental caries and periodontal disease there are some other topics that are of paramount interest to both patients and dental health care providers. These topics include:

- • Aesthetic dentistry,

- • Halitosis (bad breath), and

- • Oral issues related to aging.

Since this is a chapter in a book on Beauty and Health, we call particular attention to these latter subjects, for they are the quintessential focus of the aging population’s search to look good and feel good in their advancing years. We are all concerned, no matter our age, with how we look, and healthy white teeth that can be used to chew what we like is a fundamental quest for all.

B. Importance of Aesthetics in Dentistry

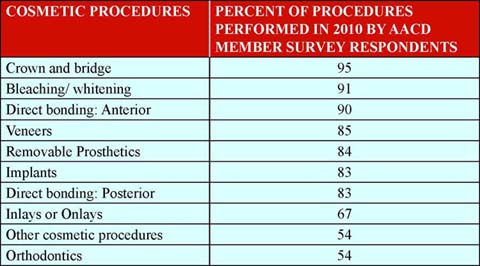

The importance of an individual’s appearance for aesthetic reasons is easy to assess, even if one did nothing but look at the sales of tooth-whitening agents. Americans spent approximately $1.4 billion on over-the-counter whitening agents in 2013.6 Every four years the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry (AACD) conducts a survey of its membership. The most widely read one, the Cosmetic Dentistry State of the Industry 2011 Survey,7 was distributed to AACD members in 2011 and had a response rate of 76% (only AACD members received the survey). Table 1 contains a list of the percentage of aesthetic procedures performed by AACD members, which these dentists have reported as distinctly not essential restorative procedures. As seen in Table 1, 85 to 95% of the procedures performed by these dentists are very expensive and procedures performed strictly for aesthetic reasons are few and far between since they are generally not covered by dental insurance.

Table 1. Percent of esthetic procedures performed by members of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry in 2010.8

Another interesting factor that resulted from analysis of the AACD 2011 survey responses is that the results indicated what the patients in these cosmetic practices really cared about most in terms of the cosmetic dentistry they received. The factor that was listed as the most important one, by 97% of the respondents, was appearance.

Along with appearance, having halitosis or bad breath is of great concern by the public. According to a popular Internet dating source9 it is estimated that in the U.S., people spent approximately $10 billion dollars per year on mouthwashes, breath mints, rinses, gum, toothpastes and other products to treat or mask halitosis. Specifically, in 2011–2012, people in the U.S. spend approximately $1.6 billion per year on toothpaste and $1.43 billion on toothbrushes and dental accessories such as interdental cleaners and dental floss. These statistics provide insight as to how important appearance and alleviation of bad breath (and oral health) is to individuals and how much money they are willing to spend on their appearance and to have fresh breath.

Before halitosis can be alleviated, the source of the bad breath needs to be detected. The source may be related to a systemic disease or problem—or, it can have origins in the oral cavity. If the oral cavity is not suspected as the source for the halitosis, the patient should be referred to a physician for evaluation of body systems. Non-oral sources for halitosis10, 11 include:

- • Nasal cavity

- • Nasopharyngeal areas

- • Sinuses

- • Oropharyngeal areas

- • Lung

- • Lower respiratory tract

- • Systemic diseases

- • Gastrointestinal diseases and disorders

- • Foods, fluids, and medications

However, 80–90% of halitosis originates in the oral cavity.12–14 Halitosis is classified into categories of genuine halitosis, pseudo-halitosis, and halitophobia. Genuine halitosis is further classified as pathogenic halitosis or physiologic halitosis. Pathogenic halitosis is further classified as oral and extra-oral halitosis, indicating that the halitosis has its origin in the oral cavity or outside the oral cavity. Patients with pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia complain about oral halitosis that does not exist. Dental healthcare providers are equipped to work with individuals who have pseudo-halitosis, but halite-phobic patients may need psychiatric treatment.

Halitosis is best measured by gas chromatography analysis. Gas chromatography is specific for identifying the concentration of volatile sulfur compounds, which is the cause of most oral malodors.10 Individuals with periodontal disease and halitosis would have their halitosis classified as pathogenic in that it results from the bacteria involved in periodontal disease. When patients have periodontal pockets of 4 mm or more, volatile sulfuric compounds are released and responsible for halitosis.

Patients with xerostomia, or dry mouth, may have halitosis, since bacteria and oral debris are not physiologically washed away as they normally would be during routine cleaning of the mouth. Giving patients with xerostomia salivary substitutes can help the halitosis if the teeth are kept as free as possible from dental plaque and the tongue is cleaned on a regular basis. Dental hygienists and dentists are poised to address the reasons for halitosis that are oral related. If a patient mentions halitosis, the dental hygienist needs to include the halitosis as something that needs to be addressed in the treatment plan. The dental hygienist can work individually with each patient to show them how to best remove the dental plaque and debris from their mouth and what products to use. This approach can be effective in helping patients prevent halitosis; if the patient does practice thorough oral hygiene and still has halitosis, he may need to be referred to medical personnel for further evaluation.

Mouthrinses and breath mints can be effective in masking some oral malodors, but usually these products have to be used repeatedly every few hours unless they have antimicrobial properties. Halitosis can be resolved in some patients with through regular dental plaque removal utilizing a toothbrush and a method for cleaning between the teeth. If dental floss is too narrow to touch the surfaces of both teeth when placed between them, then dental floss needs to be discarded and a new method of interdental cleaning should be utilized. One alternative in such cases is the use of interdental brushes. These come in several sizes and shapes and the brushes that can fill the interdental space will most likely remove the most dental plaque and biofilm.15

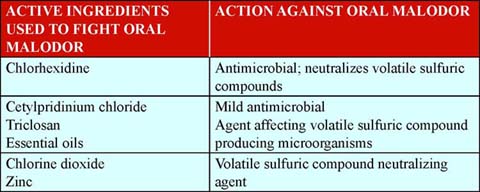

Patients will use a variety of products to fight oral malodor, in addition to using a toothbrush and interdental cleaning device. Mouthrinses that are antimicrobial such as chlorhexidine may be useful for neutralizing volatile sulfur-containing compounds. Table 2 contains a list of ingredients used to fight oral malodor and can be found in mouthrinses, toothpastes, breath mints, and chewing gum.

Table 2. List of active ingredients used to fight oral malodor and how they work to alleviate oral malodor

D. Oral Issues Related to Aging

1. Demographics of Aging: What to Expect

There is a burgeoning population of people aged 65 years and over in the United States. They are generally described as the “Baby Boomers.” These individuals represent the post-World War II generation born between the years of 1946 and 1964. In the year 2010, the “Baby Boomers” began turning age 65 and with this tipping point a new market emerged focused on the needs of these aging citizens. The growth of the population of those 65 years and over has many societal effects as the needs of these aging individuals have to be met. This growth of numbers of the aging population will have an increasingly significant effect on healthcare providers, businesses, families, and policymakers at all levels of government. It is important to be familiar with some of the “facts” related to this expanding group of aging citizens.16

- • In 2010, there were 40 million people age 65 and over who represented 13 percent of the total U.S. population; by the year 2030, 20 percent of all Americans will be age 65 or older.

- • After 2030, the growth rate of the group of individuals 65 and over is projected to remain at a steady 20 percent.

- • After 2030, the “Baby Boomers” will enter the “oldest-old population” (those 85 and over), causing this group to grow rapidly.

- • In 2010, the population of those aged 85 years and over was 5.5 million. By 2050, the U.S. Census Bureau projects that the “oldest-old population” will grow to 19 million. Further, there are some research projections that predict that the death rates of the “oldest-old population” may decline at a more rapid rate than is predicted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The current U.S. population of aging seniors has enjoyed unprecedented advances in oral hygiene and greater access to dental treatment than previous generations. Some of the advances they have benefited from include:

- • Availability of over-the-counter fluoridated toothpaste (1955) and water fluoridation

- • Availability of dental insurance in the (1970s)

- • U.S. dental healthcare providers embraced the concept of preventing dental disease rather than treating the consequences of common dental diseases. Increasingly an expanded focus has been generated in the areas of dental caries and emphasis has been placed on plaque-control programs with individualized oral hygiene instructions for patients (late 1960s and early 1970s)

- • Dental sealants (1974), fluoride varnishes, and high-fluoride toothpastes (1980s)

As a result of these advances, the majority of current seniors have all or most of their teeth.17 This presents a unique problem when these seniors enter hospitals, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities. Nursing care staff are presented with having to provide or assist these seniors with brushing and related oral hygiene procedures. Nursing staff are now required to do much more than “scrub” dentures in a sink.

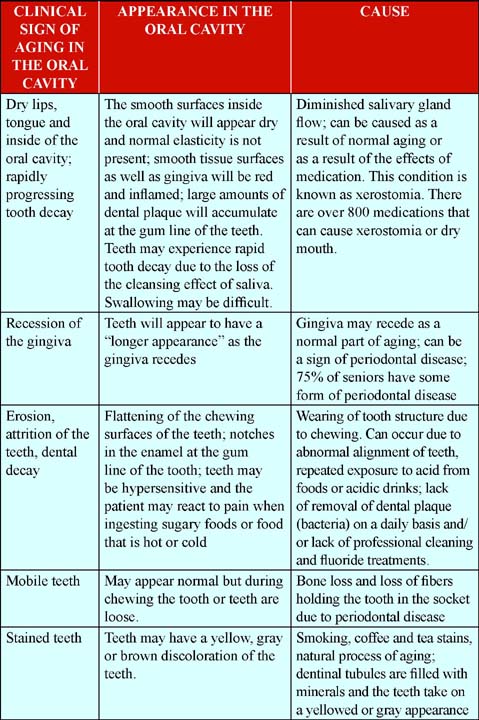

Certainly not all senior citizens reside in nursing homes or long-term care facilities. There is a distinct difference between the type of oral health issues senior citizens face, depending on whether they are living independently or live in a facility where they must depend on assistance with oral hygiene procedures. There are some oral health issues that seniors face no matter where they live and are congruent with the normal aging process. Some of the normal signs of aging that can be observed in the oral cavity of those over 65 years of age can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Clinical Signs Of Aging And The Associated Cause18

Dental examinations and professional cleaning of the teeth are as important during the senior years of life as they have been through the previous stages of life. Dentists and dental hygienists can find early signs of problems and take measures to help the patient halt damage and prevent greater damage. There are medications and products that are especially formulated to alleviate some of the symptoms of dry mouth. Professional fluoride applications in the form of fluoride treatments with trays or fluoride varnish can provide relief from hypersensitivity and the softening of enamel due to the acidic destruction process that occurs with the dental decay process.

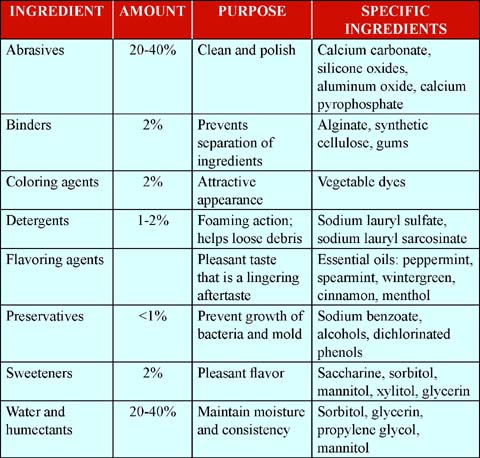

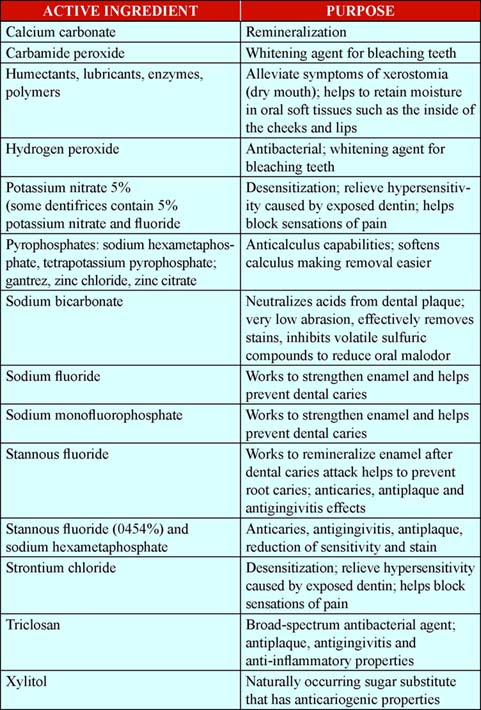

Dental healthcare professionals can recommend dentifrices that are specially formulated, for example to prevent or stop decay, stop hypersensitivity, or whiten teeth. Therefore, it is important for dental hygienists and dentists to stay abreast of advancements made with various oral care products, new benefits, and the ingredients they are formulated with. In this way they can guide their patients to the most appropriate dentifrice to meet their patient’s needs. Table 4 contains a list of popular ingredients found in dentifrices and their functions.

Table 4. Basic Ingredients in Dentifrices21

The number and type of oral care products available for personal oral care is unprecedented. Notably, there is a vast range of prices, making some of these oral care products affordable for most everyone. In 2013, $1.8 billion was spent on dentifrices and spent $775 million on toothbrushes.18, 19 There are many additional products that consumers use for oral care. These include but are not limited to products such as dental floss, interdental products for cleaning between teeth, mouthrinses, tongue cleaners (tongue cleaning is critically important to controlling halitosis), fluoride-containing products, antibacterial mouthrinses, waterflossers such as the Water-Pik, sonic devices that pulse water between teeth, and whitening products.

It is important for dental hygienists and dentists to be familiar with the various products so that when recommending a product to a patient, they can recommend the one that best fits the patient’s needs. In this Internet age, it is also important for consumers to be knowledgeable about personal oral care products as well. Otherwise, they may make purchases of products that are ineffective or not appropriate for meeting their needs. A review of dental products is important so that patients and dental healthcare providers are knowledgeable about new developments in oral care products and especially the results of research findings about the efficacy of personal oral care products. Clinical research and systematic reviews have played a crucial role in revealing which products and ingredients are the most effective.

One of the most common questions that dental hygienists and dentists are asked by patients is, “What brand of toothpaste should I use?” Most often, the response from the dental healthcare professional will be based on the patient’s needs. The conditions that are considered when professionally recommending a dentifrice are prevention of dental caries and/or the demineralization/erosion of enamel, gingivitis and/or periodontal disease, sensitivity, or stained teeth. Additionally, dental healthcare professionals most often recommend dentifrices that have the Seal of Acceptance from the American Dental Association: http://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/ada-seal-of-acceptance-program/.

1. Regulation (Therapeutic vs. Cosmetic Benefits)

The American Dental Association awards its Seal of Acceptance to dental products based on a review of: (1) the data supporting a product’s efficacy and safety, and (2) the claims made for the product, to ensure that all claims are supported by the science. Application for the American Dental Association’s Seal of Acceptance is strictly voluntary and manufacturers submit their dentifrices to the American Dental Association for testing and review. Dentists and dental hygienists need to be familiar with the wide array of dentifrices so they can guide their patients to the most appropriate dentifrice that is safe and effective and meet their needs.

It is important to note that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulates dentifrices under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. The FDA sets standards on dentifrice effectiveness and safety and regulates the amount and type of ingredients that can be in a dentifrice formulation. Table 4 contains information about the ingredients common to most dentifrice formulations regulated by the FDA.

Dentifrices are considered by the FDA to be a drug, as most dentifrices contain fluoride to prevent tooth decay or specific ingredients to treat sensitivity and gingivitis, among others. Therapeutic agents are by definition concerned with the treatment of disease. Cosmetics, as defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are “intended to be applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance without affecting the body’s structure or functions.”

Dentifrices, along with toothbrushes, are the most widely used and recommended oral products. Dentifrices have been used to freshen breath since the time of the Greeks and Romans, and have usually included abrasive agents to help remove stain. Dentifrices alone, however, will not remove dental plaque and biofilm. At this time, dental plaque must be mechanically removed. Use of dentifrices adds the benefit of containing abrasive agents that help with the mechanical removal of dental plaque and stain (thus also providing whitening efficacy) and most are flavored with the intent to freshen breath.

Another important fact that dental hygienists and dentists need to be aware of is the abrasiveness of dentifrices. There are several issues that need to be addressed when a dental hygienist or dentist recommends a dentifrice to a patient: whether the patient needs a dentifrice 1) with fluoride for dental caries prevention and/or control, 2) with antimicrobial medications for the prevention and control of gingivitis, 3) sensitivity ingredients to control dentinal hypersensitivity, and 4) with odor-controlling ingredients to manage halitosis. Another issue is the type of restorations and restorative materials that are in the patient’s mouth—especially aesthetic-restorative materials. Aesthetic-restorative materials, which include several types of tooth-colored materials, can be easily damaged with highly abrasive dentifrices.

Dentifrice abrasiveness has traditionally been determined by the Relative Dentin Abrasivity Index (RDA), a standardized test developed by the American Dental Association. One should note there are many other factors that affect the impact toothbrushing can have on hard and soft tissues, such as type of brush used (soft, medium, hard bristles), consumer habits, etc., and one should not put too much emphasis on any single factor. The maximum recommended RDA value for toothpastes is set at 250.

The abrasives used in dentifrices help remove dental plaque and stains from the tooth surface. An ideal abrasive level of a dentifrice would provide the ability to clean the tooth surfaces and remove stains without causing damage to the tooth surface or to the surface of dental restorations. The Council on Dental Therapeutics of the American Dental Association states that “a dentifrice should be no more abrasive than is necessary to keep the teeth clean—that is, free of accessible plaque, debris, and superficial stain. The degree of abrasivity needed to accomplish this purpose may vary from one individual to another.”

The abrasivity and cleaning action of abrasives are related to abrasive particle size, shape, brittleness, and hardness. The most commonly used abrasives are: hydrated silica, calcium carbonate, calcium pyrophosphate, and dicalcium phosphate dihydrate. Other materials include sodium bicarbonate, tricalcium phosphate, sodium metaphosphate, and alumina or aluminum hydroxide.

Dentists and dental hygienists need to be familiar with the wide array of dentifrices and their ingredients so they can guide their patients to the most appropriate dentifrice to meet their needs. For example, a patient may want to know what the best whitening dentifrice to buy is, but the dental hygienist has taken note that this patient has dentinal hypersensitivity. A whitening dentifrice containing hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide or a dentifrice that is highly abrasive would all be contraindicated for this patient as these types of dentifrices could worsen the dentinal hypersensitivity.

Table 5 contains a list of popular active ingredients found in dentifrices and the conditions they are intended to target. Adding active ingredients is not easily accomplished, as many potential actives can interact or react with the other ingredients. Interactions between potential therapeutic agents and inactive ingredients are well covered in a separate review.20

Table 5. List of popular ingredients in dentifrices and the functions they serve.

Abrasives. Hydrated silica

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree