One-Stage Reconstruction of the Breast Using Autologous Tissue with Immediate Nipple Reconstruction

Lawrence B. Colen

John McCraw

Since the mid-1990s, extensive clinical and laboratory research has improved our understanding of the blood supply to a wide variety of flap donor sites useful in reconstructing the absent breast. The modifications and refinements in flap elevation and transfer that have resulted have favorably influenced our ability to successfully transfer autologous tissues for this purpose. The devastating complications of flap loss, fat necrosis, and mastectomy skin slough, so common during the first years of autologous tissue breast reconstruction, rarely occur today. Modifications of the transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM) flap to include two muscular pedicles and the use of the latissimus dorsi muscle with overlying fat have consistently allowed for large volumes of autologous tissue to be safely pedicled to the chest in properly selected patients. In addition, microvascular transfers of TRAM flaps, gluteal flaps, thigh flaps, and deep circumflex iliac artery flaps have been devised so successful breast reconstructions may be obtained in high-risk patients with minimal morbidity. Efforts may now be directed toward the aesthetic and economic aspects of reconstruction.

Performing aesthetically acceptable breast reconstruction, including the creation of a nipple-areola complex during a single operative procedure, fits in well with the current trend toward reducing health care costs without compromising the reconstructive goals. If secondary procedures prove necessary, being able to accomplish them using local anesthesia in the outpatient setting proves economically superior to the major revisions that have so often been necessary in the past. This chapter presents techniques that have proved beneficial in creating an aesthetic, symmetric breast mound and nipple-areola complex in a single stage using the TRAM free flap and the autogenous latissimus flap (a latissimus dorsi flap with overlying fat with or without skin). The principles developed in this chapter should also be applicable to other flap techniques. When the tissue transfer that is performed (pedicled or “free”) is well vascularized, the flap-shaping techniques discussed here lend themselves to the performance of an immediate nipple reconstruction. Rather than the nipple reconstruction detracting from the shape obtained from the breast mound creation (which is often the case when nipple reconstruction is performed some months after the breast reconstruction), our single-stage techniques actually allow the nipple reconstruction to improve overall breast shape. In our experience, the creation of a projecting breast with a well-positioned nipple has been both safe and reliable. Using the same principles developed in this chapter, selected prosthetic reconstructions can usually also be combined with nipple reconstruction at the time of expander removal and permanent implant placement.

In keeping with the single-stage approach, any patient requiring augmentation, reduction, or mastopexy to “match” the reconstructed breast should have that procedure performed at the same time as the mastectomy and reconstruction. As one becomes more comfortable with the single-stage approach, the changes that occur with each of the previous manipulations of the opposite breast over time may be factored into the operative plan so later revisions may be avoided.

Components of Breast Shape

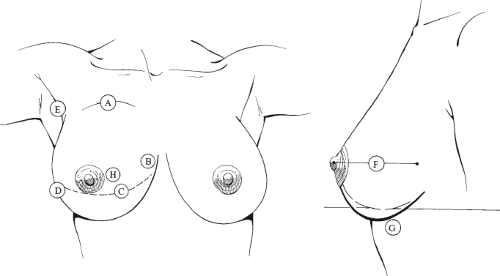

Eight components of breast shape must be addressed with any reconstructive procedure (Fig. 50.1). These include infraclavicular fill, medial cleavage, submammary crease, lateral fullness, anterior axillary fold, breast projection, ptosis, and nipple-areola shape and position. The ability to reconstruct the anterior axillary fold and infraclavicular area is a unique contribution of flap procedures because these areas of deficiency are often not fully addressed with prostheses. The medial cleavage and submammary crease components are created by the direct fixation of the flap margins to the chest wall. Projection is related to the thickness of the flap centrally and may be increased by constricting the conical base of the reconstructed breast mound on the chest wall in a manner similar to the making of a dunce cap. Ptosis is increased by a lower placement of the reconstructed breast mound with respect to the submammary fold. Conversely, more superior positioning of the reconstruction will decrease the amount of ptosis obtained. Lateral fullness, or the transition area, describes the lower outer quadrant of the breast. This region ties together the lower quadrants of the breast with the anterior axillary fold. Finally, the nipple-areola complex is an important component of breast shape. It should enhance the conical shape of the breast mound and improve breast projection rather than detract from it. The shaping techniques described in this chapter help to achieve these goals by creating a central “dog ear” of tissue that can be converted into an immediate nipple reconstruction.

Indications and Considerations

Based on our more recent experience, all patients requesting breast reconstruction may be candidates for single-stage techniques. The considerations involved with immediate versus delayed single-stage reconstruction, as well as delayed reconstruction in patients who have undergone chest wall irradiation, are different and should be reviewed.

Immediate Reconstruction

Current techniques of mastectomy require removal of the nipple-areola complex with the breast gland and must provide for access to the axilla for lymphadenectomy, either through the periareola approach or via a second, limited axillary incision. Removal of additional skin may be necessary based on the viability of the mastectomy skin flaps after breast removal, the presence of any biopsy scars, and whether a mastopexy or reduction procedure is being performed on the contralateral breast. Little, if any, flap skin is usually necessary for breast resurfacing. The flap is buried as a gland “substitute,” with the nipple-areola reconstruction performed using a small skin island on the surface of the flap. These patients are often the best candidates for a single-stage procedure, especially when the opposite breast does not require any modifications.

In these patients, it is important to form the breast shape with the flap rather than depend on the skin envelope to accomplish this goal. The breast mound is shaped and secured to the chest wall, with special attention to the natural landmarks of the breast (i.e., the submammary crease and the medial and lateral attachments of the breast skin to the chest wall). Not infrequently, the mastectomy procedure will “destroy” these attachments. If the flap is secured to the chest wall in the proper locations, it will not be necessary to place any additional sutures to recreate these landmarks. Redraping the mastectomy skin and adding a suction drain will complete the breast mound reconstruction, allowing the nipple reconstruction to be accomplished in the exact position where the original nipple-areola was resected. Little change in position of the nipple-areola should be expected in the months after surgery.

When concurrent contralateral breast augmentation is being performed, little change in the single-stage approach is required. However, changes in the operative plan are necessary when a contralateral mastopexy or reduction is contemplated. One must realize that, over time, the breast undergoing reduction or mastopexy will develop increasing fullness in the lower quadrants. However, the relationship of the nipple-areola location to the submammary crease remains a constant. The contralateral breast procedure should be performed before flap inset and shaping so the volume parameter and nipple-areola position for the reconstructed breast can be determined. This is especially true when performing a contralateral reduction mammaplasty. It is helpful to weigh both the mastectomy and the reduction mammaplasty specimens so the volume necessary for the reconstruction may be determined. After flap elevation, the tissue may be weighed and the amount of flap to be discarded may be calculated. It is our experience that the volume change in well-vascularized flaps after reconstructive breast surgery is negligible, provided no adjuvant radiation therapy has been administered.

Standard approaches to the contralateral mastopexy or reduction are used, but we have not recommended the use of the “keyhole”-type pattern skin excision for the mastectomy. Mastectomy skin flaps are generally thinner and more widely undermined than the flaps that are developed when performing a breast reduction. The contributions of the internal mammary perforators and the lateral thoracic blood supply to the breast skin are usually destroyed. After we experienced significant mastectomy skin flap slough in our first few cases, we abandoned this approach. The mastectomy is performed with a periareolar excision and an oblique extension toward the axilla

to facilitate lymphadenectomy. Skin excision is accomplished in a “free-hand” manner after the flap has been inset and shaped. Nipple-areola reconstruction may need to be delayed if its creation using flap skin that is brought through an opening in the mastectomy skin flaps would jeopardize the blood supply to the distal portions of those flaps. This is a decision that must be individualized for each patient during the operative procedure. If one proceeds with nipple-areola reconstruction, its position is determined from the nipple position on the contralateral breast. The need for revision of the nipple-areola position on the reconstructed side is rare, leading us to believe the changes that occur in nipple-areola location after breast reduction/mastopexy or breast reconstruction beneath a reduced skin envelope are similar. A progressive increase in lower pole fullness and a decrease in superior pole fullness over time after breast reduction or significant mastopexy are expected. This does not occur on the reconstructed side; hence, volume requirements and nipple position are more critical than actual volume distribution when one assesses the intraoperative result.

to facilitate lymphadenectomy. Skin excision is accomplished in a “free-hand” manner after the flap has been inset and shaped. Nipple-areola reconstruction may need to be delayed if its creation using flap skin that is brought through an opening in the mastectomy skin flaps would jeopardize the blood supply to the distal portions of those flaps. This is a decision that must be individualized for each patient during the operative procedure. If one proceeds with nipple-areola reconstruction, its position is determined from the nipple position on the contralateral breast. The need for revision of the nipple-areola position on the reconstructed side is rare, leading us to believe the changes that occur in nipple-areola location after breast reduction/mastopexy or breast reconstruction beneath a reduced skin envelope are similar. A progressive increase in lower pole fullness and a decrease in superior pole fullness over time after breast reduction or significant mastopexy are expected. This does not occur on the reconstructed side; hence, volume requirements and nipple position are more critical than actual volume distribution when one assesses the intraoperative result.

Delayed Reconstruction

The single-stage approach is well suited for delayed reconstruction of the breast. Early in our experience, small revisions to match the opposite breast were more frequent than in immediate reconstruction. This is primarily due to the fact that when the tight chest wall skin (the “old” mastectomy skin flaps) is reelevated for placement of the breast flap, it progressively loosens, causing the reconstructed breast to become more ptotic over time. These changes are similar to what occurs with the maturation of a reduction mammaplasty or large mastopexy. It is not unusual that superior portions of the skin island used for surface replacement need to be excised 3 months after reconstruction. These minor revisions, when necessary, can be performed under local anesthesia on an outpatient basis. If the “new” nipple position was accurately placed on the breast mound at the time of the reconstruction, it too will become ptotic but will be returned to a more symmetric position when the superior portions of the skin island are revised. The original relationship between the submammary fold and the nipple position does not change; hence, the only revisions we have had to perform have involved moving of the breast mound cephalad in the manner just mentioned. The need for these minor revisions has been less frequent when contralateral mastopexy or reduction is combined with the delayed single-stage reconstruction because both breasts mature in a similar manner.

As in the case of immediate single-stage reconstruction, flap inset, shaping, and nipple reconstruction should be performed after the contralateral mastopexy or reduction has been completed. The chest skin between the oblique or transverse mastectomy scar and the submammary crease is uniformly discarded because it will interfere with breast projection if burying of the autologous flap beneath this skin is attempted. Conversely, the superior components of the reconstruction are deepithelialized and buried beneath the old superior mastectomy skin flap. Occasionally, this superior skin flap may be excessively tight (especially in previously irradiated patients), and modifications may be necessary to alleviate this tightness because it will distort the smooth transition from flap skin to chest wall skin. This is usually accomplished by lengthening the edge of the superior mastectomy skin flap by either curvilinear excision or vertical incision and inset of a “dart” of flap skin island. Nipple reconstruction should be performed in an identical location to the contralateral nipple position. Although later excision of excessive flap skin island has been necessary in some of our patients, direct modification of nipple position via transposition has not been necessary.

Radiation Therapy

The effects of radiation therapy on the delayed single-stage reconstruction have been unpredictable. The reelevation of the “old” superior mastectomy skin flap that has been previously irradiated often contributes to increasing stiffness of these tissues in the months after the procedure. The usual tendency toward increasing ptosis of the breast mound seen with nonirradiated delayed reconstructions is often inhibited. When there is significant radiation effect noted involving the chest wall skin preoperatively, one may even see increasing tightness develop, which may cause the breast mound to elevate subsequent to the surgery. Significant radiation damage may therefore be considered a relative contraindication for a single-stage approach. In these difficult cases, flap skin is often required for surface replacement, leaving fewer options available for the shaping of the breast mound.

We have not noted similar problems when radiation treatments follow an immediate single-stage procedure. There may be a small amount of atrophy of the reconstruction seen within 6 months of completion of the radiation therapy, and, as such, we try to achieve a 10% to 15% increase in size of the reconstructed side when compared with the contralateral breast. Because significant changes within the mastectomy skin flaps or the breast mound have not occurred after postoperative radiation therapy, we strongly recommend the single-stage approach in this clinical situation.

Techniques

During our early experience with the TRAM free flap, we appreciated the robust circulation that this flap had when compared with the standard single-pedicle procedure. We soon realized that the TRAM free flap would tolerate rather radical shaping techniques without compromising its circulation. As a result of these findings, the single-stage breast reconstruction and nipple procedure evolved. We have performed the single-stage procedure in numerous TRAM free-flap reconstructions and have successfully adapted the same principles to their use in the latissimus dorsi adipomyocutaneous flap breast reconstruction.

Transverse Rectus Abdominus Myocutaneous Free Flap

The details of TRAM free-flap elevation are described elsewhere in this book. For a typical unilateral reconstruction, we will harvest a segment of the contralateral periumbilical rectus abdominus muscle along with the overlying skin paddle. We routinely perform our vascular repairs to branches of the subscapular vascular axis rather than the internal mammary vessels, if possible. After the flap has been revascularized on the chest wall, the rectus muscle segment should be secured to the pectoralis major muscle so the positioning and inset of the skin

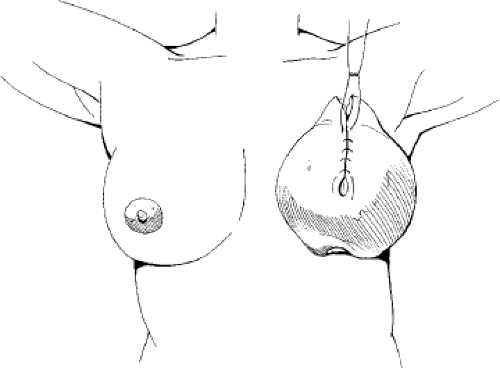

and fat components will not inadvertently cause avulsion of the vascular anastomoses. Positioning of the umbilicus usually occurs between the 5 and 7 o’clock positions, depending on which breast is being reconstructed and on the shape of the contralateral breast (Fig. 50.2). Our goal is to create a projecting breast mound by folding the flap into a U shape, with the resulting dog ear properly positioned for an aesthetic nipple reconstruction. The shape of the skin ellipse facilitates this technique, and the trimming of excess flap tissue, if necessary, should be done in a manner that preserves this elliptical shape.

and fat components will not inadvertently cause avulsion of the vascular anastomoses. Positioning of the umbilicus usually occurs between the 5 and 7 o’clock positions, depending on which breast is being reconstructed and on the shape of the contralateral breast (Fig. 50.2). Our goal is to create a projecting breast mound by folding the flap into a U shape, with the resulting dog ear properly positioned for an aesthetic nipple reconstruction. The shape of the skin ellipse facilitates this technique, and the trimming of excess flap tissue, if necessary, should be done in a manner that preserves this elliptical shape.

After revascularization, securing of the rectus muscle segment, and warming of the flap, poorly vascularized segments from zone 4 may be discarded. If the flap volume exceeds the requirements of the reconstruction, trimming may also be performed. We advocate the removal of tissue along the inferior border of the flap because this preserves a wide skin paddle that can easily be folded into a U shape (Fig. 50.2). If the flap is too long, then additional tissue from zone 4 can be removed, retaining the shape of an ellipse as much as possible.

Flap inset begins in the upper inner quadrant and proceeds in a counterclockwise manner (for a left breast reconstruction). This will help ensure adequate recreation of medial fullness and cleavage, as well as address the infraclavicular deficits. In cases of delayed reconstruction, the medial extent of the reconstructed breast may be determined by supporting the contralateral breast in a medial position (Fig. 50.3). Excessive lateral positioning of the reconstructed breast mound is an easy error to make, especially if the lateral components of the reconstruction are inset first. Concerns about tethering the vascular anastomoses by medially positioning the TRAM flap on the chest wall are not well founded. If the muscle segment harvest is periumbilical, a long vascular pedicle results and allows for a tension-free placement of the flap.

After medial reconstruction, the flap should be secured to the inframammary crease, beginning medially and coursing laterally. Adequate bulk should be placed in the lower outer quadrant to mimic the lateral fullness of the contralateral breast. Continued upward rotation of the flap completes the U shape and reconstructs the anterior axillary fold and the lateral aspects of the infraclavicular defect (Fig. 50.4). The edges of the flap are then secured together with absorbable subcutaneous sutures, completing the reconstruction of the breast mound. This will create a point of prominence at the apex of the breast mound that may be moved to the appropriate location and converted into a nipple (Fig. 50.5). For the most part, the shaping techniques used in immediate and delayed reconstruction of the breast with the TRAM free flap are similar. However, during the inset of the flap for delayed procedures, flap skin is used to reconstruct lower quadrant breast skin (only the superior portions of the breast mound are deepithelialized and buried). In immediate reconstruction, the entire flap (with the exception of the nipple-areola reconstruction) is usually deepithelialized and buried.

Figure 50.3. Medial displacement of the contralateral breast will help to locate the position of the medial extent of the reconstruction. |

Figure 50.4. The lateral extents of the flap are folded to create the U shape, which determines the base diameter of the reconstruction and the projection. |

Nipple-Areola Reconstruction

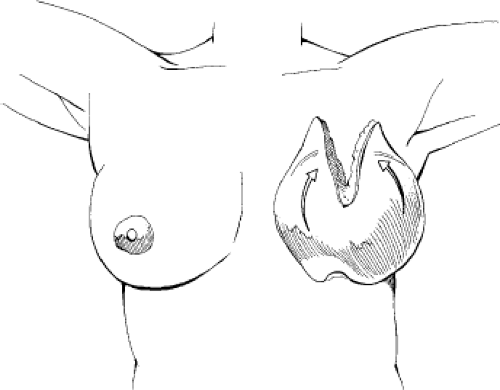

During our early experience with the TRAM free flap, the central prominence that resulted from the folding of the flap was disturbing. Deepithelialization and inversion therefore removed it in order to soften the pointlike projection of the breast mound. We soon realized that this tissue could be used for nipple reconstruction. By converting this dog ear into two flaps with a common base, they may be transposed and used to create both the cylindrical sidewalls and the top of a projecting nipple. In selected cases in which the opposite breast is ptotic and lacks youthful projection, one may create the nipple-areola component by simply outlining the location of the complex on the breast mound and using a bilobed flap of skin and fat in an identical manner to what has already been described. This is also useful when the TRAM flap has been split for bilateral reconstructions. In these cases, it is often difficult to shape the flap into a U; therefore, a dog ear does not play a significant role in nipple reconstruction. These points are illustrated in the clinical cases that follow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree