Oncoplastic Techniques in Breast Conservation Therapy—The Plastic Surgeon’s Perspective

Albert Losken

Brian Pettitt-Schieber

History

Breast-conserving therapy (BCT) continues to rise as a treatment for women with breast cancer, and we have subsequently become more aware of poor cosmetic results following radiation therapy and long term. Up to 30% of women will have a residual deformity following BCT that may require surgical correction (1), which is often challenging following radiation therapy (2). The oncoplastic approach is subsequently becoming more popular, whereby partial breast reconstruction is performed often at the time of tumor resection, to minimize or prevent these deformities. In a review of 10,607 breast cancer surgeries, the oncoplastic approach was the one procedure with the biggest increase of nearly fourfold from 2007 to 2014 (3). Werner Audretsch is credited for his pioneering work in the field of oncoplastic breast surgery, an approach which was initially more popular in Europe and the United Kingdom, and has recently gained acceptance and popularity worldwide. The oncoplastic terminology will be used in this chapter as it applies to the immediate reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect. This field has clearly been driven by both patient demands, as well as the development of combined surgical techniques, made possible through greater interaction between specialties. Patients like the oncoplastic approach because it often allows them to undergo BCT, and often without a deformity, breast surgeons like the ability to resect a generous amount without concerns about the cosmesis, and plastic surgeons bring an eye for aesthetic results and enjoy performing breast reconstruction.

The Plastic Surgeon’s Perspective

The plastic surgeon’s role in the oncoplastic approach is critically important as the initial driving force was over the minimization or correction of BCT deformities and the sole focus from their perspective is one of reconstruction. With the appropriate training and qualifications, this approach can be offered by a single surgeon; however for now in the United States, the combined team with a resective surgeon and reconstructive surgeon remains the most popular. There remains inconsistency in how this is offered in various parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, the interest in oncoplastic surgery has increased over the last 5 years with significantly more breast surgeons performing reduction techniques and latissimus dorsi flaps (4). A survey in Canada demonstrated that surgeons that were predominately focused on breast surgery were more likely to use the oncoplastic technique and involve plastic surgeons. Those not performing oncoplastic procedures cited a lack of training and access to plastic surgeons as a significant barrier (5). In a survey in the United States, both breast and plastic surgeons agreed that complex partial reconstructions were best performed using the team approach and that margin concerns were a major concern and aesthetic benefits were a major driving force in both groups (6). The plastic surgeon has been an integral part of the refinements in partial breast reconstruction and will likely continue to push the envelope in terms of new techniques and improved outcomes.

Reconstruction is a major part of the oncoplastic definition, being volume replacement versus volume displacement. Further division in the definition for oncoplastic surgery separates volume displacement oncoplastic surgery into levels 1 and 2. Specifically, level 1 volume displacement oncoplastic surgery involves reconstruction of the breast with subsequent local tissue rearrangement designs for reconstruction. Such designs would involve undermining of breast tissue, creation of glandular shelves, and are often performed by the resective surgeon. Level 2 volume displacement oncoplastic surgery involves more complex reconstruction often performed by the reconstructive surgeon and includes mastopexy or reduction mammoplasty designs to reconstruct the large volume defects with contralateral symmetry breast mastopexy or reduction mammoplasty operations. The goals of the oncoplastic approach are (1) avoid the BCT deformity, minimize positive margins,

broaden indications for BCT, avoid full mastectomy, and preserve shape.

broaden indications for BCT, avoid full mastectomy, and preserve shape.

Indications

The two main reasons to reconstruct partial mastectomy defects are:

to increase the indications for BCT making breast conservation practical in patients who otherwise might require a mastectomy, and

to minimize the potential for a poor aesthetic result (Table 34-1). The decision is typically based on tumor characteristics, breast shape, and size.

Based on these factors contributing to a poor aesthetic outcome, the oncoplastic approach is indicated whenever the potential for a poor cosmetic result exists, or patients with tumors in whom a standard lumpectomy would lead to breast deformity or gross asymmetry. In particular, this includes women with large tumors and women with large breasts. The tumor to breast ratio is one of the most important factors when predicting the potential for a poor outcome. In general, when more than 20% of the breast is excised with partial mastectomy, the cosmetic result is likely to be unfavorable (7). Women with central or lower quadrant tumors have also been shown to have a worse cosmetic outcome because of tumor location, especially when a significant amount of skin is removed. Lower quadrant lumpectomies have been shown to reduce cosmesis by 50% when compared to other quadrants. A recent study of 350 patients demonstrated that the maximal volumes of tissue resected with lumpectomy without resulting in unacceptable aesthetic and functional outcomes of decreased quality of life (QOL) were 18% to 19% in the upper-outer quadrant, 14% to 15% in the lower quadrant, 8% to 9% in the upper-inner quadrant, and 9% to 10% in the lower-inner quadrant (8).

TABLE 34-1 Indications for Immediate Partial Mastectomy Reconstruction | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Factors in addition to cosmetic reasons as an indication for this approach include oncologic issues. Important indications include situations where the surgeon is concerned about the potential for involved margins with standard resection, and based on initial pathology or breast imaging studies needs to perform a wider excision in order for the patient to be a candidate for breast-conserving surgery (BCS). Other more aggressive and higher-staged breast cancers are also amenable to oncoplastic resections and subsequently, the oncoplastic approach broadens the indications for BCT, as these patients might otherwise have required a mastectomy. Additional indications include women who desire breast conservation despite potential adverse conditions, as well as older women with large ptotic breasts in whom mastectomy and reconstruction would be difficult.

Contraindications

Contraindications to the immediate oncoplastic technique include those patients not candidates for BCS, prior history of chest wall irradiation, diffuse multicentric breast disease, inflammatory breast cancer, and those patients without sufficient breast tissue remaining to warrant BCS. If significant resection is required and little breast tissue is anticipated, then either a flap reconstruction would be required or the need for mastectomy should be discussed.

Preoperative Planning

If the oncoplastic approach is deemed necessary for the previously mentioned indications, it is important that the ablative surgeon and reconstructive surgeon communicate and understand the various perspectives. The ablative surgeon must recognize the concept of breast shape, symmetry, and aesthetics and anticipate an unfavorable result without intervention as well as the reconstructive options. It is equally important that the reconstructive surgeon not compromise the oncologic tenets of cancer management in an attempt to improve breast shape. In an attempt to anticipate the defect size and location relative to the nipple-areolar complex, it is helpful to review the films following wire placement and further discuss the plan with the breast surgeon in terms of the best approach and incision location. Members of the surgical team examine the patient, identify her expectations and desires, and evaluate breast size, shape, and tumor characteristics. A contralateral breast procedure is often required when volume preservation techniques such as flap reconstructions are not used.

It is important to decide the best time to do partial breast reconstruction. When indicated, it is better to perform immediate reconstruction at the time of tumor resection (see Table 34-1). This has the benefits of operating on a nonirradiated or surgically scarred breast, resulting in lower complication rates and improved

aesthetic results (9,10). This is often preferred since it is only one procedure performed on the breast prior to radiation therapy. Reduction techniques prior to radiation therapy result in significantly lower complication rates when compared to performing reductions after completion of radiation therapy (21% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) and Kronowitz has shown similar results (24% vs. 50%) (10). The main concern with immediate reconstruction is the potential for positive margins. When this concern does exist, the reconstruction can be delayed until final confirmation of negative margins (delayed-immediate reconstruction). This then allows the benefits of reconstruction prior to radiation therapy with the luxury of clear margins. The main disadvantage is the need for a second procedure, which might be unnecessary in most cases. When a flap reconstruction is required, we prefer to confirm final margin status prior to partial breast reconstruction. There are situations where poor results are encountered years after following radiation therapy, which then require correction (delayed reconstruction). Since the delayed approach requires operating on an irradiated breast, this often has higher postoperative complications, increased need for flap reconstruction, and poorer aesthetic outcomes.

aesthetic results (9,10). This is often preferred since it is only one procedure performed on the breast prior to radiation therapy. Reduction techniques prior to radiation therapy result in significantly lower complication rates when compared to performing reductions after completion of radiation therapy (21% vs. 57%, p < 0.001) and Kronowitz has shown similar results (24% vs. 50%) (10). The main concern with immediate reconstruction is the potential for positive margins. When this concern does exist, the reconstruction can be delayed until final confirmation of negative margins (delayed-immediate reconstruction). This then allows the benefits of reconstruction prior to radiation therapy with the luxury of clear margins. The main disadvantage is the need for a second procedure, which might be unnecessary in most cases. When a flap reconstruction is required, we prefer to confirm final margin status prior to partial breast reconstruction. There are situations where poor results are encountered years after following radiation therapy, which then require correction (delayed reconstruction). Since the delayed approach requires operating on an irradiated breast, this often has higher postoperative complications, increased need for flap reconstruction, and poorer aesthetic outcomes.

Operative Technique

The decision as to which procedure is more appropriate is multifactorial, however, is ultimately determined by breast size, tumor size, and tumor location (Table 34-2). Other factors are also important including patient risks and desires, tumor biology, and surgeon comfort level with the various techniques. Being familiar with the various reconstructive tools will allow reconstruction of almost any partial mastectomy defect.

Volume Displacement Techniques

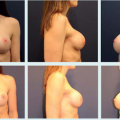

The breast reshaping procedures all essentially rely on advancement, rotation or transposition of a large area of breast to fill a small- or moderate-sized defect. This absorbs the volume loss over a larger area. Perhaps the most popular and versatile breast reshaping options that involve reconstructive surgeons are the mastopexy or reduction techniques. The ideal patient is one where the tumor can be excised within the expected breast reduction specimen, in medium to large or ptotic breasts where sufficient breast parenchyma remains following resection to reshape the mound (type 2b defects). Any moderate to large breast can be reconstructed using these techniques unless a skin deformity exists beyond the standard Wise pattern (type 2a defect).

In women with large or ptotic breasts, the numerous reduction patterns or pedicle designs will invariably allow remodeling of a defect in any location and any size, as long as sufficient breast tissue and skin is available. Preoperative markings are important, and a decision is made on pedicle design depending on tumor location. Typically, if the pedicle points to or can be rotated into the defect, it can be used. The Wise pattern markings are more versatile allowing tumor resection in any breast quadrant. The breast surgeon often performs the lumpectomy through an incision within the Wise pattern markings. Once the resection is performed, the cavity is inspected paying attention to the defect location in relation to the nipple, as well as the remaining breast tissue. The reconstructive goals include:

preservation of nipple viability,

filling the tumor defect and closing the dead space, and

reshaping the breast mound.

TABLE 34-2 Partial Mastectomy Reconstruction Techniques | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Once a decision has been made as to the most appropriate pedicle for nipple preservation, and it has been determined how to fill the lumpectomy cavity, only then should additional tissue be removed to reduce and shape the breast mount. The contralateral procedure is performed using a similar technique. The ipsilateral side is typically kept about 10% to 15% larger to allow for radiation fibrosis. When the partial defect cannot be filled with the standard breast reduction techniques in women with smaller ptotic breasts or more peripheral defects, then autoaugmentation techniques can be utilized. These include either extending the primary nipple pedicle to fill the defect or creating a secondary independent pedicle to fill the defect. These techniques have been shown to further broaden the indications for the oncoplastic technique without increasing complications.

Volume Replacement Techniques

Women with large tumor to breast ratios and women with small to moderate breasts who have insufficient residual breast tissue for rearrangement require partial reconstruction using nonbreast local or distant flaps. Volume is preserved and a contralateral procedure is often not required.

Small lateral defects (less than 10% of breast size) can be closed with local fasciocutaneous flaps. Clough described using the subaxillary area as a transposition flap (11), and Munhoz has more recently demonstrated how the lateral thoracodorsal flap (LTDF) is ideal for lateral defects (12). The latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap is a common local option for lateral, central, and even medial defects (13). It has excellent blood supply and provides both muscle for filling of glandular defects and skin for cutaneous deficiencies. A denervated and radiated LD will undergo postoperative atrophy. To compensate for the expected loss in muscle volume, a flap much larger than the defect should be harvested, possibly preserving sub-Scarpa fat on the muscle. Hamdi introduced the concept of pedicled perforator flaps for partial breast reconstruction (14,15). A similar skin island to the classical LD musculocutaneous flap can be raised as a perforator flap either from the thoracodorsal or intercostal vessels. By sparing the underlying muscles, the donor site morbidity is less, with less seroma formation. The thoracodorsal artery perforator (TDAP) flap can easily reach defects in the lateral, superolateral, and central regions of the breast. If no suitable perforators are found, the flap is easily converted to a muscle-sparing TDAP or LD flap. The lateral intercostal artery perforator (LICAP) flap is another alternative to the TDAP flap for lateral and inferior breast defects. The LICAPs are found at 2.7 to 3.5 cm from the anterior border of the LD muscle. The anterior intercostal artery perforator (AICAP) flap is similar to the random-designed thoracoepigastric skin flap; the skin paddle can be harvested as an AICAP flap. The AICAP is based on perforators originating from the intercostal vessels through the rectus abdominis or the external oblique muscles. Since it has a short pedicle, the AICAP flap is suitable to close defects that extend over the inferior or medial quadrants of the breast. The superior epigastric artery perforator (SEAP) flap is based on perforators arising from the superior epigastric artery or its superficial branch. It has the same indications as the AICAP flap; however, the SEAP flap has a longer vascular pedicle and therefore it can cover more remote defect in the breast. Large medial defects are more difficult to reconstruct. The superficial inferior epigastric artery free flap has been described for this location (16).

Postoperative Care

Most patients have minimal postoperative care. One important difference from the plastic surgeon’s perspective is the importance of reviewing the pathology and margin status and being involved in the decision process and procedure if reexcision is planned. It is also important to manage complications appropriately and in a timely fashion so as not to delay initiation of adjuvant therapies. Another area of involvement postoperatively is with surveillance. The reconstructive surgeon will occasionally need to educate the radiologist in terms of what was done and how this might impact breast imaging down the line. Oncoplastic reduction techniques and flap reconstruction techniques have not been shown to interfere with the ability to screen for postoperative tumor recurrence (17,18).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree