Oncoplastic Surgery: Managing Common and Challenging Problems

Alexandre Mendonça Munhoz

Introduction

Breast conservation surgery (BCS) is an important part of early breast cancer treatment, with a survival outcome comparable to that of radical procedures (1). Recently, increasing attention has been focused on oncoplastic procedures because the reconstructive techniques provide a wider local excision while still achieving the goals of a better breast form (2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16).

Introduced by Audretsch et al. (17,18) in 1998, oncoplastic surgery is a relatively new but increasingly used procedure. It combines principles of oncologic and plastic surgery techniques to obtain oncologically sound and aesthetically pleasing results (2). Despite the acceptance that most BCS can be managed with primary closure, the aesthetic result may be unpredictable and occasionally can be complex to reconstruct (3,4,5,6,7,9). Thus, by means of customized techniques the surgeon ensures that oncologic principles are not jeopardized while meeting the needs of the patient from an aesthetic point of view.

In general, these techniques involve volume displacement or replacement techniques and sometimes include contralateral breast surgery (7). Among the procedures available, local flaps, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap, and reduction mammaplasty/mastopexy techniques are the most commonly employed (3,4,6,7,8,9). Regardless of the fact that there is no consensus concerning the best approach, the decisive criteria are determined by the surgeon’s experience and the size of the defect in relation to the size of the remaining breast (6,7,8,9). The main advantages of the technique utilized should include reproducibility, low interference with the oncologic treatment and long-term results. Probably, all these goals are not achieved by any single procedure, and each technique has advantages and limitations (8).

Managing Common Problems

Timing of Reconstruction

Oncoplastic reconstruction may begin at the time of BCS (immediate), weeks later (delayed-immediate), or months to years afterward (delayed). Surgical planning and timing of reconstruction should include breast volume, tumor location, and the extent of glandular tissue resected, enabling each patient to receive an individual “custom-made” reconstruction (8).

Immediate Reconstruction

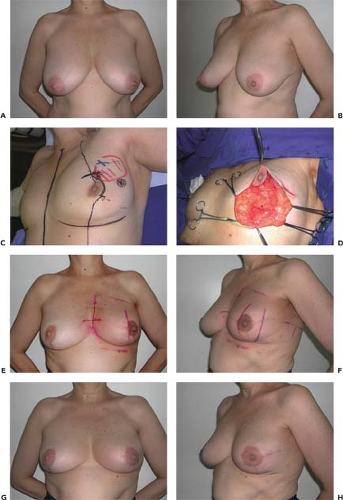

With immediate reconstruction, the surgical process is smooth because both procedures can be associated in one operative setting. In addition, because there is no scar tissue, breast reshaping is easier, and the cosmetic results are improved (3,5,6,7,9). Some studies advocate that the ideal treatment should be preventive by performing immediate reconstruction before radiotherapy (3,4,5,6,7,9,18,19). Papp et al. (19) observed that the aesthetic results showed a higher success rate in the immediate group when compared with delayed reconstruction patients. Similarly, Kronowitz et al. (6) observed that immediate repair is preferable to delayed repair because of a decreased incidence of complications (Fig. 11.1).

In terms of oncologic advantages, immediate reconstruction can be beneficial. Some studies have observed that patients with macromastia present more radiation-related complications than patients with normal-volume breasts (16,20,21). In addition, some authors suggested that there is an increased fat content in large breasts, and the fatty tissue results in more fibrosis after radiotherapy than glandular tissue (22) (Fig. 11.2).

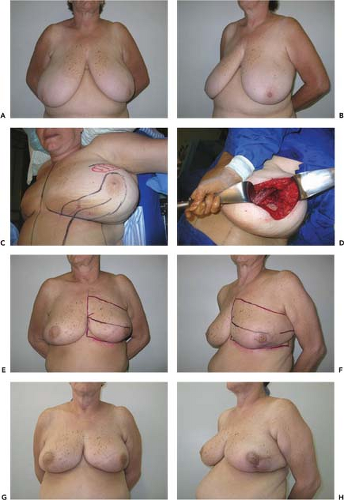

Gray et al. (21), in a series of 257 patients, found that there was more retraction and asymmetry in the large-breasted versus the small-breasted group. Thus, breast reduction can increase the eligibility of large-breasted patients for BCS since it can reduce the difficulty of providing radiation therapy (7,9,16,20,21).

Another aspect is the possibility of accomplishing negative resection margin. In fact, the immediate reconstruction allows for wider local tumor excision, potentially reducing the incidence of margin involvement (3,7,23). Kaur et al. (23) compared patients submitted to oncoplastic procedures and to BCS. The oncoplastic approaches permitted larger resections, with a superior mean volume of the specimen and negative margins.

Another positive aspect is the opportunity of examining the opposite breast. Despite the low incidence of occult malignancy observed in aesthetic breast reductions, the risk undoubtedly increases in patients with previous breast cancer (3,7,8,12,24). In our previous study (24), 4.3% of the patients submitted to opposite mammaplasty were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Despite the benefits, the immediate reconstruction presents limitations. The surgical time can be lengthened, and potential complications can unfavorably affect the aesthetic outcome. It can be time consuming, technically demanding, and require specialist training to learn and properly apply these procedures (2,3,7). Despite these limitations, the immediate approach can reduce deformities, favor the oncologic treatment, and optimize the aesthetic outcome in most early-stage cancer patients.

Delayed Reconstruction

Some patients are so distressed by their cancer diagnosis that they are not capable of significantly participating in reconstructive considerations, and delayed reconstruction defers decisions about it. Another important point is related to postoperative radiation, which may adversely affect the aesthetic outcome of an immediate BCS reconstruction. One might

surmise that the final contour of the breast cannot be predicted at the time of the BCS. It is well accepted that radiation usually involves some degree of fibrosis and shrinkage. Some authors observed that although the aesthetic outcome can be satisfactory, the appearance of the radiated breast is occasionally less pleasing than that of the nonradiated one (3,4,5,6,9,12,15,25). Thus, in delayed reconstruction the plastic surgeon waits until the postoperative changes in the deformed breast stabilize (9) (Fig. 11.3).

surmise that the final contour of the breast cannot be predicted at the time of the BCS. It is well accepted that radiation usually involves some degree of fibrosis and shrinkage. Some authors observed that although the aesthetic outcome can be satisfactory, the appearance of the radiated breast is occasionally less pleasing than that of the nonradiated one (3,4,5,6,9,12,15,25). Thus, in delayed reconstruction the plastic surgeon waits until the postoperative changes in the deformed breast stabilize (9) (Fig. 11.3).

Concerning the delayed reconstruction management, Clough et al. (4) proposed a classification based on response to the type of reconstruction. Patients with a type I breast defect have a normal breast with no deformity. However, there is asymmetry between the contralateral breasts. These patients were reconstructed with contralateral breast surgery (see Fig. 11.3). Type II patients have clearly deformed breasts, and the defect is repaired with ipsilateral breast surgery or flap reconstruction. Type III patients have major deformity and were treated with mastectomy and reconstruction (Fig. 11.4).

Another controversy is related to the postoperative recovery. In theory, some complications of the immediate reconstructions can unfavorably defer the adjuvant therapy. With the delayed approach, operative time is shortened and the surgical process is less extensive than in the immediate approach. However, our previous experience (8,10,11,12,13,24) and that of others (5,26) has shown that immediate reconstruction does not compromise the start of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the overall treatment of breast cancer.

Delayed-Immediate Reconstruction

By definition, two-stage procedures can be delayed-immediate, with initial wide local excision and then oncoplastic reconstruction with appropriate technique at that time when the histologic margin assessment has been performed (7,9,27,28). In this approach, it is possible to postpone reconstruction until after the review of the final pathology report and the definitive surgical margins (Fig. 11.5). If partial breast reconstruction is done at the time of BCS and the patient is found postoperatively to have surgical margin involvement, reexploration can be troublesome. Therefore, the advantage of two-stage procedures relate to the possibility of accurate location of the original tumor site in the cases where positive margins are observed in the permanent pathology (27). However, the delayed-immediate approach can present some limitations. There are some technical difficulties in operating on a previously treated breast, for example, recent scar tissue and fibrosis. The procedure can be time consuming and demands additional costs, which may have additional resource implications for community hospitals (27).

Indications: Classification and Choice of the Reconstructive Method

Partial breast defects represent an anatomic variety that ranges from small defects that may be repaired with primary closure to large defects that involve a significant amount of breast tissue. Each defect has its special reconstructive necessities and varying expectations for aesthetic outcome. The decision is usually determined by the surgeon’s preferences and the size of the defect in relation to the size of the remaining breast. On the basis of our 9 years of experience, it is possible to identify trends in types of breast defects and to develop an algorithm for immediate BCS reconstruction on the basis of the initial breast volume, the extent/location of glandular tissue resection, and the remaining available breast tissue (8).

Partial Breast Defects Classification

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree