Impact of Reconstructive Transplantation on the Future of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Keywords

• Vascularized composite allografts • Disadvantages of reconstructive transplantation • Face transplant • Hand transplant • Abdominal wall transplant • Laryngeal transplant • Tracheal transplant

Introduction of reconstructive transplantation into plastic surgery

As a result of the lack of “specialized spare parts” that could be borrowed from the bodies to restore missing functions, the idea of reconstructive transplantation was borne and introduced to plastic surgery. It was based on more than 20 years of experimental and preclinical work testing the technical, functional, and, most importantly, immunologic aspects of reconstructive transplantation.1–15

Reconstructive transplantation as an alternative surgical option

Reconstructive transplantation includes VCAs and involves transplantation of tissues derived from ectoderm and mesoderm. VCAs typically contain skin, fat, muscle, nerves, lymph nodes, bone, cartilage, ligaments, and bone marrow as opposed to a single tissue organ, which is the case in conventional solid organ transplantation. An example of VCA is limb transplantation, in which the transplanted graft includes skin, muscle, nerve, blood vessels, and bone. The function and immunologic properties of the composite tissue transplant are more difficult to define, because each individual component has its own unique characteristics that ultimately affect the successful outcome of the transplantation. Most applications of VCA predominantly improve quality of life for patients with non–life-threatening conditions and aim to restore anatomic, cosmetic, and functional integrity. The benefits gathered from these procedures must be balanced against the morbidity of the surgical procedure itself, the side effects of lifelong immunosuppression therapy, and the cost of surgery and immunosuppressive medications (Box 1).

Disadvantages

Advances in VCA transplantation have opened a new era in the field of reconstructive surgery. Since 1998, after the report on the first successful hand transplantation in France, the field of VCA has further developed, opening new alternatives for patients who have lost their extremities and hands.16

On November 27, 2005, in Amiens, France, a surgical team led by Drs Bernard Devauchelle and Jean-Michel Dubernard announced that they had performed a partial face transplant on a 38-year-old woman whose face had been disfigured by a dog bite.17 To date, a total of 19 face transplantations have been performed worldwide in France, China, the United States, and Spain.18–32

The world’s first near-total face transplantation was performed in Cleveland in December 2008 by a team led by this author.23 This procedure was, until now, the most complex face transplant, involving restoration of 3-dimensional craniofacial skeleton with multiple functional units.

Cleveland Clinic Near-Total Face Transplantation Procedure

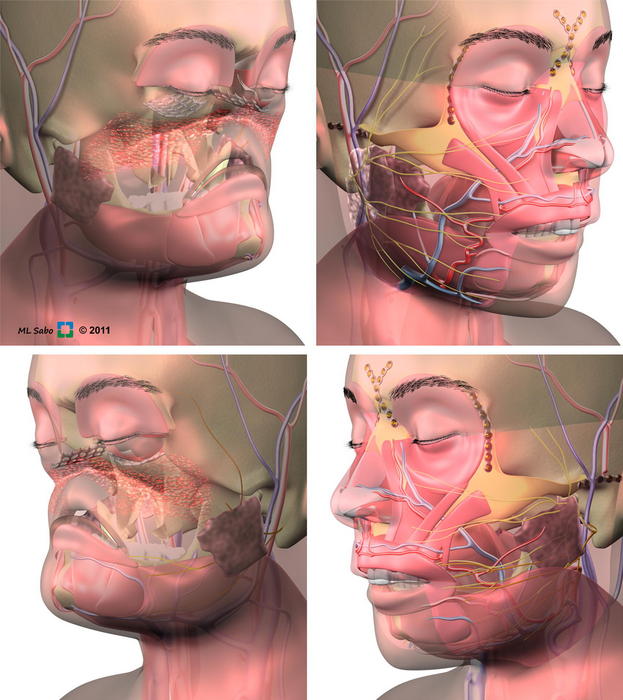

The patient was a 45-year-old woman who experienced severe facial trauma to her midface from a close-range shotgun blast in September 2004. Her facial deformities included absence of nose, nasal lining, and underlying bone; contracted remnants of the upper lip; loss of orbicularis oris and orbicularis oculi muscle functions; distorted and scarred lower eyelids with ectropion; right-eye enucleation supported by eye prosthesis; and facial nerve deficit manifested by the lack of midface function (Fig. 1).

The donor was a brain-dead woman who matched the patient in age, race, and skin complexion. The allograft was designed to cover the recipient’s anterior craniofacial skeleton, and it included approximately 80% of the surface area of the anterior face. It was based on a Le Fort III composite tissue allograft containing total nose, lower eyelids, upper lip, total infraorbital floor, bilateral zygomas, and anterior maxilla with incisors, and included total alveolus, anterior hard palate, and bilateral parotid glands (Fig. 2).24,25

Fig. 2 Schematic illustration of the first U.S. near-total face transplantation (for patient in Fig. 1). Figures representing recipient defect before allograft insert (top left and bottom left) illustrating the need for a 3-dimensional craniofacial reconstruction. This face allograft included more than 535 cm2 of facial skin, functional units of full nose with nasal lining and bony skeleton, lower eyelids and upper lip, and underlying muscles and bones, including orbital floor, zygoma, maxilla with teeth, hard palate, parotids and nerves, and arteries and veins (top right and bottom right).

(Courtesy of The Cleveland Clinic Education Institute (CCEI) and staff illustrator Mark Sabo, BFA, Cleveland, OH; with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree