Occupational Noneczematous Skin Diseases Due to Biologic, Physical, and Chemical Agents: Introduction

|

Skin Diseases Due to Biologic Agents

Workers in healthcare, food services, cleaning and maintenance, and outdoor occupations are at a risk of developing skin infections. Table 212-1 lists some of the occupations associated with increased risk of certain infections.1

| Occupational Groups at Risk137 | Infections |

|---|---|

| Agricultural workers, farmers, shepherds, cattle workers, ranchers, animal scientists, animal breeders, veterinarians | Orf, milker’s nodules, tinea barbae dermatophyte infections, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, sporotrichosis, cutaneous larva migrans |

| Athletes (wrestlers, surfers, swimmers, football, hockey and beach volleyball players, triatheletes) | Herpes gladiatorum, tinea corporis gladiatorum, impetigo, furunculosis, seabather’s eruption, swimming pool granuloma (M. marinum), pseudomonas (“hot tub”) folliculitis, acne mechanica, cutanea larva migrans |

| Butchers, meat handlers, abattoir workers138 | Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections, cutaneous anthrax, viral warts, erysipeloid, tularemia, brucellosis, leptospirosis |

| Construction and other outdoor workers | Blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, arthropod bites |

| Cooks, bakers, food handlers, dishwashers, cannery workers, bartenders, others doing wet work | Candidal intertrigo, paronychia, pseudomonas folliculitis |

| Fish merchants and fishermen | Staphylococcal, streptococcal infections, erysipeloid, vibrio vulnificus, aeromonas hydrophilia |

| Foresters, hunters | Tularemia, Lyme disease |

| Gardeners | Sporotrichosis |

| Hairdressers, manicurists | Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections |

| Healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, dentists, physician and dental assistants, respiratory therapists, paramedics) | Herpes simplex (herpetic whitlow), HIV infection, hepatitis, staphylococcal and streptococcal infections, candidiasis |

| Laboratory workers | Brucellosis, tularemia, HIV infection, hepatitis, monkeypox |

| Military personnel | Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections, dermatophyte infections, arthropod bites, leishmaniasis |

| Pet shop workers, aquarium handlers, fish tank cleaners | Fish tank granuloma (Mycobacterium marinum), monkeypox |

| Veterinarians | Cutaneous tuberculosis, cutaneous anthrax, brucellosis, tularemia, orf |

Establishing a definite relationship between work and a specific infection is not always simple. Laboratory isolation of the infective organism and a supporting medical history and physical examination are helpful.

Another area of particular concern is the rise in incidence of multidrug-resistant organisms. This has been a growing problem for many years with the dilemma playing a particularly important role in the management of wounded military personnel. With an increased number of troops being deployed overseas to active combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, the issue of antibiotic resistance complicates wound management in situations where resources may be relatively sparse.2 The most frequently identified strains of resistant organisms contaminating battlefield wounds are Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumanii, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Pseudomonas aerugenosa.3,4

(See Chapter 176.) Secondary bacterial skin infections due to Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are common complications of abrasions, lacerations, burns, and puncture wounds. Butchers and meat handlers are likely to develop infected cuts and scratches, paronychia, abscesses, and lymphangitis. Folliculitis and boils are common in farm workers and construction workers. Workers in hot, humid, and dirty environments5 (see eFig. 212-0.1) or those working in close contact with infected persons, such as nurses, hairdressers, and manicurists, are at risk. Metalworking and other industrial fluids contaminated with bacteria are another potential source of infection for workers and have even been implicated in an outbreak of Pseudomonas folliculitis.5,6 The increase in multidrug-resistant bacterial strains and the emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus7 may present a therapeutic challenge.

Infectious eczematoid dermatitis frequently follows contact dermatitis that is untreated and in an area where there is constant rubbing. In this case, the patient was a logger working in an area with poor access to medical attention.

(See Chapters 183 and 213.) Anthrax, caused by Bacillus anthracis, is primarily seen in cattle, sheep, horses, goats, and wild herbivores. Occupational exposure to infected animals or their products (such as skin, wool, and meat) is the usual pathway of exposure for humans. Agricultural workers, stockbreeders, butchers, and meat processors can become infected by contact with diseased animals. Contaminated hides, goat hair, wool, and bones can infect dockworkers, freight handlers, warehouse workers, and employees of processing plants that handle these products. Tanners, carpet makers, and upholsterers are also at risk, as well as laboratory workers handling specimens.8

Anthrax also poses a particular risk to the general population and military personnel as an agent of germ warfare owing to the highly infectious nature of its spores (see Chapter 213).9–11 Closely following the attacks of September 11, 2001, a series of anthrax exposures were reported, the result of contaminated letters sent via the United States Postal Service. A total of 22 cases, including 10 cases of inhalational anthrax and 12 cases of cutaneous anthrax, occurred over a 1 month period.12 During the ongoing investigation conducted by the FBI and the CDC, a laboratory worker assigned to the case was exposed to the organism via infected vials and contracted cutaneous anthrax.13 These attacks highlighted the dangers of infectious agents as potential weapons of biological warfare and renewed interest in appropriate administration of the anthrax vaccine.

(See Chapter 184.) Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, a slow-growing warty papule or plaque caused by the exogenous inoculation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis in previously sensitized individuals, has been reported in pathologists and morgue attendants (prosector’s or anatomist’s wart).14 Surgeons, veterinarians, farmers, and butchers are also at risk, although the condition is rare at the present time.

The Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, prepared using live attenuated M. bovis, is given to prevent the development of tuberculosis. There have been reports of scrofuloderma, with skin changes overlying cold abscess formation in the underlying subcutaneous tissue at the site of inoculation. Additionally lupus vulgaris (LV), or paucibacillary cutaneous infection caused by hematogenous, lymphatic or contiguous spread from the site of inoculation15 has occurred after an extended latency period of up to 17 years after administration of the vaccine.16 Although the United States has never routinely administered the BCG vaccine, in some instances, individuals who are at particularly high risk (e.g., healthcare workers repeatedly exposed to drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis) may receive the vaccine.17 Furthermore, it was standard policy to inoculate school-aged children even in the United Kingdom until 2005. Given reports of long latency between vaccine administration and occurrence of lupus vulgaris, continued awareness and surveillance is advisable when caring for UK citizens.

Numerous atypical (i.e., nontuberculous) mycobacteria cause cutaneous and systemic disease. Mycobacterium marinum causes swimming pool or fish tank granuloma, a solitary or disseminated granulomatous infection seen in fishermen, fish tank cleaners, aquarium workers (eFig. 212-0.2), and workers cleaning contaminated swimming pools.18 Surgeons are also at risk. Granulomas also may form in a linear fashion along lines of lymphatic drainage (so-called sporotrichoid spread).

Less common atypical mycobacteria may cause infection in the setting of immunosuppression (such as AIDS), as well as in immune competent hosts with high-risk exposure in an occupational setting. There have been case reports of Mycobacterium simiae causing a cutaneous granulomatous infection in animal handlers scratched by primates.19 Infection with this particular mycobacterium is complicated by its multidrug resistance and requires culture and susceptibility testing.20 There are also reported cases of veterinarians and livestock handlers contracting cutaneous mycobacterial infections, such as cutaneous infection with M. bovis caused by exposure to an infected alpaca and lupus vulgaris caused by M. bovis sp. caprae caused by exposure to dairy cattle.21,22

(See Chapter 183.) Brucellosis is a zoonosis transmitted to humans via contact with infected animals or ingestion of untreated milk or milk products. Farmers, livestock breeders, meatpackers, veterinarians, and laboratory workers are at risk.23 An epidemic caused by sniffing bacterial cultures has been reported.24

(See Chapter 183.) Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis, a Gram-negative bacillus transmitted by ticks, fleas, and deerflies. Animal reservoirs include wild rabbits, squirrels, birds, sheep, beavers, muskrats, and domestic dogs and cats. Tularemia is seen in hunters, trappers, game wardens, butchers, fur handlers, and laboratory workers. It is highly infectious, and great care should be exercised in handling infected tissues and excreta. All laboratory personnel who may handle samples from a case of suspected tularemia should be forewarned.

(See Chapter 183.) Erysipeloid is almost always an occupational disease and is caused by Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, a Gram-negative rod that infects freshwater and saltwater fish, ducks, emus, turkeys, chickens, and other farmed animals such as sheep.25 Butchers, fishermen, scuba divers, and retailers of fish and poultry are commonly affected.26

(See Chapter 193.) Infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV) is the most common viral infection of occupational origin. Infections due to HSV type 1 or 2 are seen in occupations in which there is exposure to infected secretions from the mouth or the respiratory tract. Dentists, dental assistants, nurses, and respiratory technicians are particularly vulnerable, and herpetic whitlow is a common problem.27 Infection with HSV-1 after a needle-stick injury has also been reported.28 Herpes labialis is a common problem in woodwind and brass instrumentalists.29 HSV infection on the body surfaces of wrestlers and rugby players, known as herpes gladiatorum, is temporarily disqualifying for infected athletes. In healthcare professions, the implementation of universal precautions has led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of infection.30

Needle-stick injuries are a well-recognized occupational hazard for healthcare workers, putting them at risk of acquiring an infectious disease from blood-borne pathogens. The average risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission after a percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected blood has been estimated to be approximately 0.3%.31,32 For hepatitis B, the risk of clinical hepatitis if the blood was positive for both hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B envelope antigen is reported to be 22% to 31%; the risk is 1% to 6% if the blood was positive for hepatitis B surface antigen but negative for hepatitis B envelope antigen.32 A 95% decline in hepatitis B virus infection in healthcare workers was noted from 1983 to 1995, largely due to widespread immunization of healthcare workers with the hepatitis B vaccine.33 The average incidence of antihepatitis C virus seroconversion after accidental percutaneous exposure to a hepatitis C virus-positive source is 1.8% (range, 0%–7%).32 The most accurate data on needle-stick and sharps injuries are derived from prospective studies, which yield an estimated annual incidence ranging from 562 to 839 injuries per 1,000 healthcare workers per year.34 Nurses have the most patient contact, and it is not surprising that this occupational group accounts for most reported cases.34,35 Immediate evaluation of the injured employee is necessary to assess the risk related to exposure and the need for postexposure prophylaxis (antiretroviral therapy for HIV, immunoglobulins and vaccination for hepatitis B virus). A substantial reduction in needle-stick injuries with the use of needleless systems or newer safety needle devices and blunt suture needles has been noted, though still not widely implemented due to questions of relative efficacy compared to older technology.33,36 Examples of needleless systems include, but are not limited to, intravenous delivery systems that administer medication or fluids through a catheter port or connector site using a blunt cannula or other nonneedle connection, and jet injection systems that deliver subcutaneous or intramuscular injections of liquid medication through the skin without the use of a needle.

The CDC has published guidelines for the management of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) in the setting of occupational exposure to HIV.37 The indication for PEP depends on the type of exposure, such as percutaneous injury versus mucous membrane and nonintact skin exposure, as well as the severity of injury and the volume of fluid exposure. In cases of less high-risk exposure, such as solid needle superficial injuries and mucous membrane or nonintact skin exposures from HIV-positive individuals who are asymptomatic or known to have low viral loads, a basic two-drug PEP regimen is the current CDC recommendation. In higher risk exposures, such as deep puncture wounds and wounds from large-bore hollow needles from symptomatic individuals and those with high viral load or in acute seroconversion, the current recommendation is a three-drug postexposure prophylaxis regimen. Ideally, drugs in the regimen are chosen from different classes of antiretrovirals and exert their effects at different stages in the viral replication cycle, thus increasing efficacy and reducing or prolonging potential drug resistance. The drug classes include nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NtRTI), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI), protease inhibitors (PI), and fusion inhibitors (FI).

(See Chapter 196.)

Handlers of meat, poultry, and fish have a high prevalence of viral warts, which is likely attributable to the acquisition of minor cuts and abrasions during work. Human papillomavirus 7 has been isolated more frequently in this group of patients.38

(See Chapter 195.) Professional wrestlers and boxers are prone to developing molluscum.

(See Chapter 195.) Orf, caused by a parapoxvirus, is endemic in sheep and goats, and is easily transmitted to humans through direct contact. Veterinarians, farmers, and shepherds are at risk.39

(See Chapter 195.) The paravaccinia virus, which infects the udders of cows and produces ulcers in the mouths of calves, can be transmitted to dairy farmers and veterinarians, causing milker’s nodules (or pseudocowpox)40 (see eFig. 212-0.3).

(See Chapter 195.) An outbreak of human monkeypox in the United States in 2003 was traced to a shipment of infected exotic African rodents, some of which escaped, that produced secondary infection in wild prairie dogs housed at the same pet store. Exposure to these infected prairie dogs resulted in 37 human infections involving exotic pet dealers, pet owners, and veterinary care workers.41 Although human-to-human transmission rate of monkeypox virus is thought to be low, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends strict contact, droplet, and airborne precautions for healthcare workers. The case-fatality rate has been less than 10% in Africa, with children being more vulnerable to fatal infection.42 Smallpox vaccination is recommended for healthcare workers and household contacts of confirmed monkeypox cases per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

(See Chapter 188.) Dermatophytic skin infections are seen more frequently in farmers and animal husbandry workers.43 Infections with Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes, which are seen in the general population, may occur in work situations involving increased perspiration and occlusion. Microsporum gypseum, T. mentagrophytes, and verrucosum verrucosum cause infection in agricultural and other outdoor workers (see eFig. 212-0.4). M. canis infects veterinarians and laboratory workers. Physiotherapists who perform hydrotherapy are also more likely to develop fungal skin infections.44 An unusual tinea corporis infection in a scientist due to a laboratory strain of Arthroderma benhamiae has been reported.45 There is a report of a laboratory worker developing erythema multiforme secondary to cutaneous infection with T. mentagrophytes contracted from contact with research animals.46

(See Chapter 189.) Infection with Candida albicans is common in occupations that expose the skin to moisture and occlusion, such as those that require wearing gloves for long periods of time. Food handlers, surgeons and nurses, dental assistants, dishwashers, laundry workers, and tollbooth attendants are at risk.

(See Chapter 190.) Sporotrichosis, caused by Sporothrix schenckii, is acquired by inoculation through puncture wounds from thorns, sticks, or splinters. It is seen in farmers, nursery and forestry workers, and those in other outdoor occupations. Gardeners working with sphagnum moss used for packing plant roots may also be at risk. There have been reports of disseminated and bilateral sporotrichosis mimicking sarcoidosis and prurigo nodularis, respectively.47,48

(See Chapters 185 and 190.) Mycetoma, caused by various species of fungi and actinomycetes, is seen mainly in farmers and outdoor workers in tropical and subtropical countries; walking barefoot is a risk factor.

(See Chapter 190.) Chromoblastomycosis, a deep mycosis, often follows a puncture wound or other trauma during which soil-inhabiting fungi of Phialophora, Hormodendrum, and Fonsecaea species are injected deep into the tissues. Agricultural and other outdoor workers are at risk.

(See Chapter 190.) Those at risk of blastomycosis include agricultural, forestry, and construction workers, farmers, and persons working with heavy earth-moving equipment in endemic areas, such as the Mississippi and Ohio River basins.49

(See Chapter 190.) Coccidioidomycosis is acquired by the inhalation of dust containing the spores of Coccidioides immitis. Farmers, construction workers, bulldozer and heavy equipment operators, and laboratory workers are susceptible.

There has been an increase in the incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the US military personnel who were deployed to southwest or central Asia or other areas in which leishmaniasis is endemic, with hundreds of cases having been reported to date.50–52 The larvae of Ancylostoma braziliense and Necator americanus cause creeping eruption (cutaneous larva migrans) in agricultural workers, fishermen, sewer workers, and lifeguards. Skin divers, lifeguards, dockworkers, and caretakers who maintain lakes and ponds are prone to development of swimmer’s itch caused by the cercariae of a schistosome; there is also a report of swimmer’s itch developing after cleaning of an aquarium.53 Dogger Bank itch is seen in fishermen and dockworkers in the North Sea, who are exposed to the marine bryozoan Alcyonidium gelatinosum.

In contrast to swimmer’s itch, lifeguards, swimmers and professional divers can develop seabather’s eruption, commonly called “sea lice,” which is papulopustular dermatosis caused by the thimble jellyfish, Linuche unguiculata. The life cycle of L. unguiculata has three distinct stages: (1) larva (planula), (2) ephyra, and (3) adult (medusa). The eruption appears to be a hypersensitivity reaction to the venomous nematocysts discharged by the larval form of the jellyfish becoming trapped under clothing, and occurs most frequently from spring through summer. There have been reports of the eruption being caused by nematocysts discharged by adult jellyfish as well.54,55

The bites of bees, wasps, hornets, ants, ticks, mites, centipedes, and millipedes frequently cause work-related skin disease. Outdoor workers, food handlers, chicken farmers (chicken mites), workers in food-processing plants, restaurant workers, and dockworkers may be affected. Epidemics of scabies have occurred in nursing homes, hospitals, and other residential facilities for the aged56 Lyme disease (see Chapter 187) is transmitted through a tick bite and can affect outdoor construction workers, loggers, ranchers, and park rangers in wilderness areas.57

Skin Diseases Due to Physical Agents

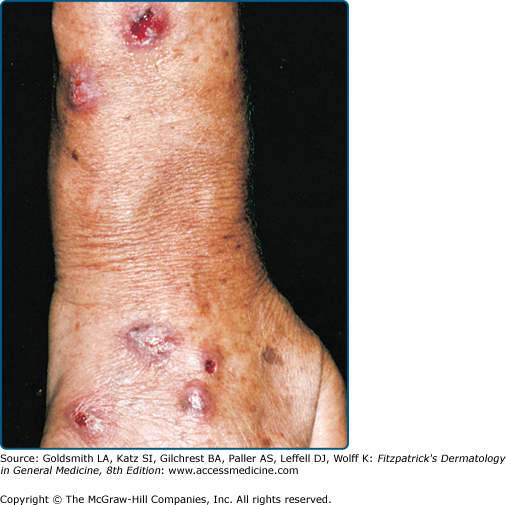

The skin may be subjected to friction, pressure, cuts, lacerations, and abrasions in the workplace. Repeated mechanical trauma such as low-intensity pressure or friction, the most common mechanical trauma, leads to hyperpigmentation and lichenification, whereas heavier and persistent friction leads to hyperkeratosis and callus formation (eFig. 212-0.5). Sudden shearing forces may lead to the formation of friction blisters, erosions, or ulcers.58 Prolonged and excessive pressure may produce hyperpigmentation and thickening, characteristic as the stigmata of various occupations59 (Fig. 212-1). Besides calluses and corns, occupational marks include discolorations, telangiectasias, tattoos, and deformities. Greater automation and better protective clothing, especially a wider selection of gloves, have decreased the incidence of occupational marks. In musicians, clinical presentation and location of skin lesions are usually specific for the instrument used (e.g., fiddler’s neck, cellist’s chest, guitar nipple, flautist’s chin).60 In athletes, repetitive trauma from running may lead to black heel or talon noir as well as blisters and jogger’s toe.60 Corns may also develop due to extreme pressure associated with bony deformities, poor foot mechanics, or improper footwear.61 A new group of skin disorders related to prolonged computer use leading to repetitive trauma (mousing callus) and prolonged pressure (computer palms) has been described.62,63 Underlying skin conditions in patients such as psoriasis and lichen planus may be aggravated by occupational trauma (koebnerization). Preexisting dermatitis caused by friction and pressure may predispose to the development of allergic sensitization.64

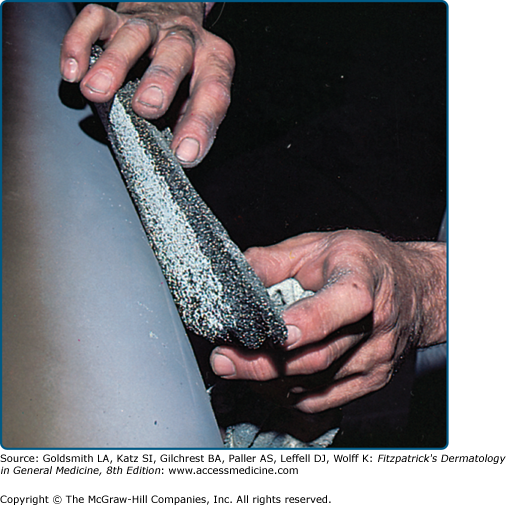

Hyperkeratotic hand eczema is a chronic hyperkeratotic, scaly, fissured dermatitis involving the palms seen in workers engaged in manual work involving repeated friction and pressure (Fig. 212-2). Pulpitis may be seen on the fingertips in women engaged in domestic work as a dry, scaly, fissuring, painful dermatitis.65 A similar condition may be seen in dental personnel allergic to acrylates, in which paresthesias of the fingertips are reported. Posttraumatic eczema (dermatitis in loco minoris resistentiae) is dermatitis at the site of cutaneous trauma. The eczema usually develops within a few weeks of the acute injury and may persist or recur for long periods of time.65 The damage and functional alteration of the skin is thought to play a role in precipitating the eczema. Table 212-2 lists the types of posttraumatic eczema and provides some examples.66

|

|

|

|

Granulomas may form due to penetration of the skin by foreign material; they may be immunogenic or nonimmunogenic. Table 212-3 lists the causes of occupational skin granulomas.67 The penetration of human hair into the interdigital spaces of barbers and of cow and sheep hair into the hands of animal tenders can produce foreign-body granulomas.68

| Causative Substance (Setting) |

|

|

Workers are at risk for thermal burns as a result of scalding; contact with liquid metal, hot equipment, and tar; and flame burns after explosions. Kitchen workers and adolescents working in fast food restaurants may develop scalds from hot grease.69 Roofers frequently incur hot tar burns, whereas explosives and flammable liquids cause most industrial burns. Persons working in foundries and smelting plants are at risk for molten metal burns. Firefighters are also at risk, although the use of protective gear reduces the extent of burn injuries.70 Workers experiencing prolonged or repeated exposure to heat and those using laptops on their laps for prolonged periods can develop erythema ab igne.71 Acne vulgaris, rosacea, and herpes simplex may be aggravated by the heat of open furnaces, heat torches, ovens, and stoves. Heat-induced cholinergic urticaria may result from strenuous physical exercise or a very warm work environment.