Clinical and histopathologic features of nonmelanoma skin cancer, physical examination, and diagnostic methods (biopsy, dermoscopy, confocal microscopy) are summarized. A diagnostic algorithm provides a useful summarization of differential diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, Bowen’s disease, and squamous cell carcinoma.

- •

In most nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) tumors, diagnosis is easy for their typical morphologic appearance; however, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate the pigmented or nonpigmented skin lesions clinically.

- •

With the naked eye, only half of pigmented lesions are correctly diagnosed; dermoscopy increases the diagnostic sensitivity to 95%.

- •

Besides diagnosis, dermoscopy and confocal microscopy have the advantage of selection of location for biopsy, determination of appropriate therapeutic modalities, verification of treatment efficacy, and decision of surgical margins.

- •

The central zone of the face, temples, lips, ears, and the scalp have significant risk for local recurrence and metastases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Similar to basal cell carcinoma, the growth of SCC tends to follow the regions of the least resistant, spreading along the perichondrium, periosteum, fascia, and embryonic fusion planes.

Introduction

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is the most common skin cancer affecting both sexes. In most of these tumors, diagnosis is easy for their typical morphologic appearance ; however, it may sometimes be difficult to differentiate the pigmented or nonpigmented skin lesions clinically.

Dermoscopy is a practical technique for the evaluation of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions, including melanoma and NMSC. It is a noninvasive and inexpensive in vivo tool that permits the visualization of morphologic features that are not visible to the naked eye. With the naked eye, only half of the pigmented lesions are correctly diagnosed. Dermoscopy, which is useful in the differential diagnosis of melanocytic and nonmelanocytic lesions, increases the diagnostic sensitivity to 95%. A 10-fold magnification is generally sufficient for the assessment of the suspicious skin lesions, but magnifications up to ×100 are possible.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) is a new optical method that is useful for obtaining the detailed images of tissue architecture and cellular morphology of living tissues. It does not need fixation, sectioning, and staining, but provides in near real-time imaging with a high resolution and contrast. In contrast to vertical sections in histologic evaluation, RCM obtains horizontal (en face) optical sections in gray scale. These horizontal images of the skin at the cellular resolution can be viewed from the surface down to 150 μm, which is the depth of the papillary dermis. A digital camera connected to the RCM computer obtains dermoscopic images directly correlated with RCM evaluation and guides the identification of suspicious areas within the lesion. RCM has been used for the evaluation of a variety of inflammatory and neoplastic skin disorders.

Although these 2 easy methods are useful for clinicians in the diagnosis and follow-up, histopathological evaluation is still the gold standard; however, the 2 methods decrease unnecessary excision rates and are useful in the monitoring of the new lesions and recurrences. Here, clinical, histopathologic, dermoscopic, and RCM features of NMSC are reviewed.

Basal cell carcinoma

Clinical Findings in Basal Cell Carcinoma

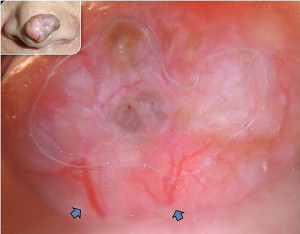

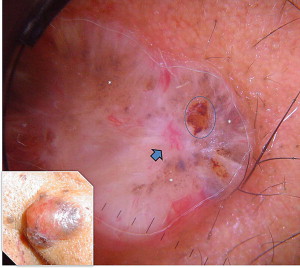

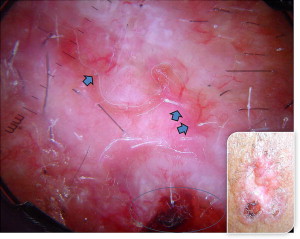

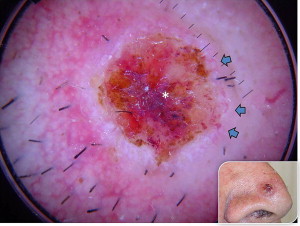

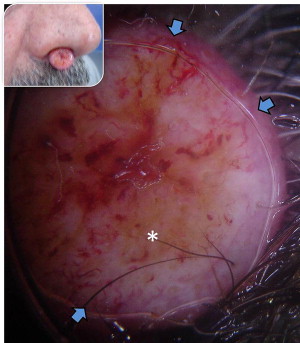

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) has clinical variants that are nodulo-ulcerative, morpheaform, infiltrative, superficial, basosquamous, cystic, and fibroepitheliomatous. The most common type, nodular BCC, occurs mainly on the face as a firm, “pearly” papule or nodule with a telengiectasic surface. In time, the dome-shaped lesions tend to be eroded and ulcerated. Nodular BCC accounts for 75% to 80% of all cases ( Fig. 1 ). Approximately 90% of nodular BCCs are found on the head and neck. These may be heavily pigmented because of the presence of melanin, so that it is sometimes impossible to exclude melanoma by only visual inspection ( Fig. 2 ). The superficial type of BCC is the second common subtype of BCC (15%), which mainly affects the trunk and the extremities; however, it can be localized on the head and neck area also ( Fig. 3 ).

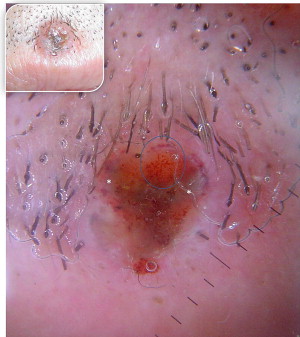

The less common infiltrative ( Fig. 4 ) and morpheaform ( Fig. 5 ) types can be seen as poorly defined, lightly pigmented, indurated, flat skin lesions, occasionally with overlying telangiectasia. The lesion may also appear scarlike without a history of skin injury. The head and neck are involved in 95% of these cases. The overlying skin surface may be atrophic, ulcerated, or relatively normal in appearance.

Basosquamous BCC, described as metatypical BCC, is a rare subtype, and is intermediate to nodulocystic BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) ( Fig. 6 ).

Cystic types have a clear or blue-gray appearance and exude a clear fluid if punctured or cut. If the lesion is in the periorbital area, it may be confused with a hidrocystoma. Cystic degeneration in a BCC is not often obvious clinically, thus the lesion may sometimes appear as a typical nodular BCC ( Fig. 7 ).

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus is a rare variant of BCC, which usually presents as a smooth pinkish nodule or plaque on the lower back. It may be difficult to distinguish it clinically from amelanotic melanoma, but it has unique histologic features. Sometimes it may be pedunculated.

BCCs are typically slow-growing lesions up to 1 or 2 cm in diameter. BCC usually remains local and almost never spreads to other parts of the body; however, it may invade nearby tissues and structures, including the nerves, bones, and brain, especially the histologically aggressive subtypes. Metastases of BCC are rare, occurring in only 0.003% to 0.05% of patients, and most commonly occur via the lymphatics to the regional nodes.

Histologic subtype of the tumor, age of the patient, and the anatomic location are the most important factors in identifying high-risk BCC. The midface region, which comprises the nasal dorsum, nasal tip, nasal ala, nasolabial folds, philtrum, inner canthus, and forehead, seems to have the highest recurrence rate. The auricular and periauricular areas are the next most frequent sites for recurrence. All these preferred anatomic sites are because of an increased UV exposure. The skin and subcutaneous tissue in these areas are relatively thin, which permits tumor spreading along the periosteum and perichondrium. The embryologic fusion planes in these regions also provide easy paths for spreading.

Histopathology of BCC

BCC is an adnexal tumor composed of tumor nests with aggregates of basaloid cells and characteristic palisading. The peripheral cells surround the less-organized cells in the center of tumor nests. The nuclei of tumor cells are generally uniform and hyperchromatic, and the cytoplasm is scanty and poorly demarcated.

BCC has distinct histologic types, like its clinical variants. Any histologic variant may be locally aggressive and metastasize, but those with basosquamous, morpheaform, infiltrating, and micronodular growth patterns seem to do so more frequently. Some of the most important subtypes listed as follows are selected either because of their frequency of occurrence or their aggressive nature.

The cell clusters are composed of rounded and bluntly branched lobules of small hyperchromatic cells, which are connected to the overlying epidermis by narrow cords or broad trabeculae. The tumor cells are uniform in size and polygonal in shape, with generally oval nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. The nuclei of the peripheral cells of the clusters are aligned in parallel and at right angles to those in the center of the nodules; so-called “peripheral palisading.” Another common finding is retraction artifact, or “cleft formation,” which is the result of shrinkage of mucin during tissue fixation and staining. Zero to 2 mitotic figures are typically seen per high-power field, but up to 10 may be observed in selected cases. Peritumoral actinic elastosis is almost invariably seen in the surrounding dermis. Not uncommonly, centrilobular necrosis in nodular BCCs accounts for their cystic quality. The overlying epidermis may or may not be ulcerated.

The histologic characteristics of superficial BCC include buds and irregular proliferations of tumor cells attached to atrophic epidermis, and they show little or no penetration into the dermis.

The morpheaform type is named so because of the densely collagenized, hypocellular fibrous matrix that is an integral part of its growth pattern. Inflammation is characteristically sparse or absent, and palisading is not present. The connection between the tumor and epidermis is usually focal. Morpheaform BCC is characterized by its deep invasion of the dermis. The overlying skin surface may be atrophic, ulcerated, or relatively normal.

Infiltrative BCC lesions are hybrids of the nodular and morpheaform types in that they show a combination of expansive solid cellular, branched, sharply angulated, and linear cell groups. These lesions lack a central cohesive mass and have a distinctive fibroblast-rich stroma. Although virtually all BCCs permeate the dermis and, hence, are “infiltrative” by definition, the term infiltrative BCC is reserved for this aggressive histologic subtype that can expand both peripherally (like morpheaform subtypes) and show deep extension to underlying soft tissue.

The micronodular type is considered biologically distinct from other subtypes of BCC because of its high propensity for local recurrence. Similar to infiltrating BCC, these lesions have the propensity for dispersion of the nests of epithelial cells. These neoplasms are made of small, round aggregates of basal cells rather than large aggregates, as seen in solid BCCs.

Basosquamous BCC includes distinct but admixed components of BCC and overt SCC. The distinction between these lesions and SCC is that they retain the typical organization of basal cell carcinoma, that is, islands of epithelial cells embedded in a fibrovascular stroma.

Dermoscopic Findings in BCC

In most cases, the diagnosis is easy with the typical morphologic appearance; however, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate pigment-containing BCCs from melanomas because of their asymmetric pigmentation. Dermoscopy is a practical tool for the evaluation of pigmented skin lesions in routine clinical examination. This technique is important especially in the diagnosis of an early melanoma. Various dermoscopic criteria have been identified in the differential diagnosis of melanocytic or nonmelanocytic pigmented skin lesions. Menzies described the criteria for the dermoscopic diagnosis of pigmented BCCs: the absence of a pigment network and the presence of at least 1 of 6 positive morphologic features: ulceration, multiple blue-gray globules (see Figs. 2 and 3 ), leaflike areas (see Fig. 3 ), arborizing vessels (see Figs. 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 and 7 ), large blue-gray ovoid nests, and spoke wheel areas.

The presence of arborizing vessels is the dermoscopic hallmark of pigmented BCC and can be appreciated even better in the nonpigmented nodular type (see Fig. 1 ). Dermoscopic examination of these lesions is recommended, especially when the differentiation from SCC and keratoacanthoma is difficult on clinical grounds. The latter ones are characterized by hairpin vessels surrounded by a whitish halo (dermoscopic sign of keratinization) and dotted vessels ( Figs. 8 and 9 ), whereas BCC nearly exclusively displays arborizing vessels ( Table 1 ). Pigmented BCC also sometimes can be difficult to distinguish clinically from melanoma. Besides the pathognomonic vascular pattern consisting of vessels with different diameters and numerous branches, leaflike areas with an opaque gray-brown to slate-gray pigmentation, mostly situated at the periphery of the lesion, represent additional dermoscopic clues for the diagnosis of BCC. However, only gray dots/globules and irregularly outlined gray structures are sometimes visible. In conjunction with the complete absence of other melanoma-specific dermoscopic criteria, these gray structures may lead to the diagnosis of BCC. Menzies’ method gives an overall sensitivity of 93% for BCC and specificity of 89% using the invasive melanoma set. Dermoscopy showing the characteristic criteria for pigmented BCC plays an important role in diagnosis.

| Clinic | Pathology | Dermoscopy | RCM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal cell carcinoma | Pearly papule/nodule with pigmentation, ulceration, or scarlike features | Basaloid cell islands in the dermis and palisatic arrangement of tumor cells, peritumoral cleft formation | Arborizing vessels, multiple blue-gray globules, leaflike and spoke-wheel areas and ulceration | Basaloid aggregations, typical palisading of tumor cells and peritumoural dark cleftlike spaces |

| Actinic keratosis | Multiple discrete, flat or elevated, keratotic plaques | Aggregates of atypical, pleomorphic keratinocytes at the basal layer that may extend upward to involve the granular and cornified layers | Red pseudonetwork pattern and white keratotic hair follicle openings, white/yellow surface scales, linear or wavy vessels | Atypical keratinocytes, nuclear and cellular pleomorphism, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, blood vessel dilation and solar elastosis |

| Bowen disease | Slowly enlarging, flat, pink, scaly patch or plaque | Proliferation of atypical, pleomorphic keratinocytes involving the whole epidermis | Glomerular vessels and a scaly surface, sometimes irregular pigment globules | Atypical honeycomb pattern with great variations in cell and nuclear morphology and whole thickness of the epidermis |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Sharply demarcated pink plaques often with ulceration and multiple actinic keratoses | Crowded keratinocytes, atypical mitosis, loss of maturation, nuclear pleomorphism, dyskeratotic cells extension in the dermis | Typically polymorphous blood vessels on center of the lesion, surrounded by whitish halo with hairpin vessels and scales | Atypical cobblestone or honeycomb patterns at the epidermis with a proliferation of atypical keratinocytes |

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy for BCC

BCC is generally considered to be the most common primary malignant neoplasm in human beings. Because they grow exceedingly slowly, most BCCs are innocuous; however, if they are not treated properly, they can cause extensive local tissue destruction, and may lead to death by infiltrating and destroying vital structures. Therefore, clinical monitoring of tumor persistence or recurrence after the treatment is important. Where local recurrence or persistence is suspected, biopsy is generally required for the diagnostic confirmation. Dermoscopic examination in monitoring treatment response may be limited if scarring is present. At this point, RCM may be useful.

RCM can detect specific BCC features that correlate with histopathology. The clinical application of this technique showed excellent diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of BCC. In the epidermis, a streaming pattern of elongated monomorphic keratinocyte nuclei that are polarized along one axis on the background of variable epidermal disarray is a feature often found. In the papillary dermis, cell aggregations with a nodular/cordlike growth pattern can be seen, as well as peritumoural dark cleftlike spaces. These are consistent with the basaloid aggregations of a BCC that often display the typical palisading of tumor cell nuclei, and the latter represents peritumoural mucinous edema. The vascular pattern has been reported to play an important diagnostic role. Vessels that are branched and orientated parallel to the horizontal surface have been described in BCCs. Infiammatory infiltrate and the presence of bright dendritic cells and melanophages (in pigmented BCC) are also often observed. With its relatively high correlation with standard microscopy findings, RCM has been used to assess treatment responses to imiquimod and photodynamic therapy. Similarly, RCM imaging of shave biopsy wounds is feasible and demonstrates the future possibility of intraoperative mapping in surgical wounds.

Basal cell carcinoma

Clinical Findings in Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) has clinical variants that are nodulo-ulcerative, morpheaform, infiltrative, superficial, basosquamous, cystic, and fibroepitheliomatous. The most common type, nodular BCC, occurs mainly on the face as a firm, “pearly” papule or nodule with a telengiectasic surface. In time, the dome-shaped lesions tend to be eroded and ulcerated. Nodular BCC accounts for 75% to 80% of all cases ( Fig. 1 ). Approximately 90% of nodular BCCs are found on the head and neck. These may be heavily pigmented because of the presence of melanin, so that it is sometimes impossible to exclude melanoma by only visual inspection ( Fig. 2 ). The superficial type of BCC is the second common subtype of BCC (15%), which mainly affects the trunk and the extremities; however, it can be localized on the head and neck area also ( Fig. 3 ).

The less common infiltrative ( Fig. 4 ) and morpheaform ( Fig. 5 ) types can be seen as poorly defined, lightly pigmented, indurated, flat skin lesions, occasionally with overlying telangiectasia. The lesion may also appear scarlike without a history of skin injury. The head and neck are involved in 95% of these cases. The overlying skin surface may be atrophic, ulcerated, or relatively normal in appearance.

Basosquamous BCC, described as metatypical BCC, is a rare subtype, and is intermediate to nodulocystic BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) ( Fig. 6 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree