Nipple-Areola Reconstruction

Scott L. Spear

Justin E. West

The creation of a nipple-areola complex is the final step of breast reconstruction in which a surgically created mound is transformed into an aesthetically pleasing breast. Over the years numerous procedures have been developed for nipple reconstruction in an effort to overcome the ongoing challenge of maintaining sustained nipple projection. This loss of projection is generally reported between 50% and 70% of initial height and is seen with both flap and implant breast reconstruction (1). Flattening of the nipple is the number one source of patient dissatisfaction, followed by color match, shape, size, texture, and position (2).

A spectrum of techniques is available for reconstruction of the nipple, including composite nipple grafts, the star flap, the double-opposing tab design, the bell flap, the C-V flap, and the skate flap. When the goal of projection is greater, a skate flap can be designed of large enough proportions with the help of a donor-site skin graft. Central or island-based flaps are no longer recommended because of inconsistent projection of long-term results. When a particularly projecting or substantial nipple is present on the nonoperated side, a composite nipple graft may have special appeal. The reconstructed nipple can also be augmented at the time of the initial procedure by augmenting with various materials between the skin flaps. Small pieces of dermal fat grafts, cartilage grafts, or AlloDerm may be placed and may contribute to both initial and long-term projection.

Timing: Immediate Versus Delayed

Nipple-areola reconstruction is typically performed as a component of the final stage of breast reconstruction. A principal argument for delay is the difficulty in determining the ideal position of the nipple-areolar complex when the effects of postoperative settling of the breast mound are unpredictable and the need for revision possible. At our institution patients reconstructed with flaps generally have the nipple created 3 months after the initial surgery. For patients with tissue expanders, nipple reconstruction may be performed at the time of exchange to implant or 3 months after the second stage has been completed.

Others have reported good outcomes with immediate nipple reconstruction. Delay and colleagues (3) reported residual projection of 6.8 mm at 2 years after immediate nipple reconstruction with dermal fat flaps during immediate latissimus breast reconstruction. Results of a questionnaire by Delay demonstrated that immediate nipple reconstruction was important to the majority of the patients and that it may encourage better acceptance of the new breast. Williams et al. (4) reported a series of immediate nipple reconstructions on free TRAM flaps. Williams et al. suggested that when a skin-sparing mastectomy is performed through a periareolar incision, positioning the nipple is easy, although they conceded that the ideal application for immediate reconstruction is in bilateral cases.

Timing of areola reconstruction depends on the technique employed. If a skin graft is to be used, it is performed at the same time as nipple reconstruction. An appropriate-size circle is marked and deepithelialized and a full-thickness skin graft is secured in place around the nipple with a bolster dressing. If a tattoo technique is to be used, it may be done at the same time as the nipple reconstruction or performed in a delayed fashion. At Georgetown University Hospital nipple reconstruction is done in the operating room, and tattooing is done by specially trained nurses in the clinic 3 months later.

Positioning the New Nipple

Proper position of the nipple on the breast and reasonable symmetry of position are important. Even small degrees of asymmetry are noticed by the least-observant viewer. When breast mounds are inherently asymmetric, the goal of acceptable symmetry is yet more difficult. The reconstructed nipple-areola must appear centric on its reconstructed breast mound yet symmetric both in and out of clothing with the contralateral side. Often, a compromise must be sought; therefore, optimal nipple-areola position is best pursued after optimal symmetry between the two breast mounds has been achieved.

Marking the new nipple position is done with the patient in the standing position. One factor to consider is where the nipple would look best on the breast mound. For cases in which a bilateral reconstruction was performed this may lead to relatively symmetric nipple position. However, in unilateral cases the ideal position on the reconstructed breast mound may not correlate with the nipple position on the contralateral breast. It may be preferable to make a mirror image of the contralateral nipple so that the nipples sit in the same horizontal plane. Ultimately the placement will likely represent a compromise between these landmarks.

To obtain the most satisfactory result, it is important to involve the patient in the ultimate decision of nipple placement. Patients are encouraged to mark where they think the nipple should be placed, either the night before or the morning of surgery. An alternative is to provide the patient with an electrocardiograph sticker the day before surgery that she may try out in various positions to help in making an informed decision.

Radiation and Nipple Reconstruction

Radiation therapy disrupts normal wound-healing mechanisms. The untoward effects include changes in vasculature, fibroblast function, and regulatory growth factors that ultimately result in the potential for compromised healing. As

such, radiation is considered by some to be a contraindication to nipple reconstruction.

such, radiation is considered by some to be a contraindication to nipple reconstruction.

Babak and colleagues (5) published a retrospective review of 28 nipples reconstructed with local flaps in irradiated breasts. There was 1 total nipple loss resulting in implant exposure and removal. The authors reported that factors predictive of a bad outcome include a history of delayed healing or necrosis of the mastectomy flaps, thin mastectomy flaps, or a history of surgical-site infection. They suggested the following criteria in selecting appropriate patients for nipple reconstruction following radiation therapy: resolution of acute radiation changes, no evidence of late radiation changes, and appropriately thick mastectomy flaps. These guidelines in conjunction with a patient-specific evaluation should help in the selection of patients with a high likelihood of success.

Nipple Reconstruction Techniques

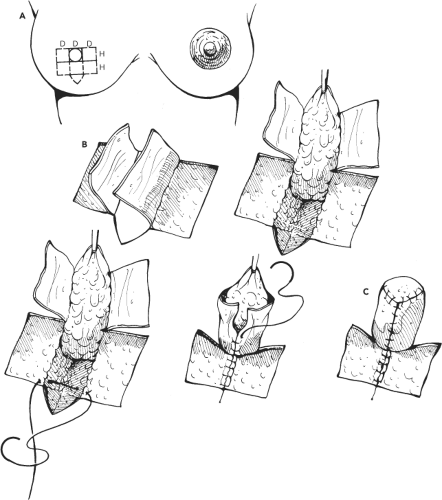

Skate Flap—Little Technique

Having picked the preferred site for the nipple, one designs the new nipple as a circle of equal diameter to the opposite nipple. If scars are present at the site of reconstruction, the design is rotated to best exclude scars from the wings of the flap design. If there is general tightness of skin at the reconstruction site, the design is rotated to allow the greatest ease of closure of the dermal donor site as determined by gently pinching the skin around the various axes of the site. If no such concern presents itself, the flap is oriented vertically with the nipple seam at 6 o’clock, hidden from the patient’s view. A transverse tangent is drawn to the nipple circle at 12 o’clock, at a length slightly more than three nipple diameters. The height of the opposite nipple is doubled to determine the design length along the central axis. This simple two-to-one overcorrection is the key to satisfactory nipple reconstruction. Significant late loss of projection occurs with any technique and must be taken into account. Rarely does extension of the design along the height axis contribute to closure difficulty; such is more likely to occur when expanding along the width or tangent base of the design. To obtain consistently satisfactory results in nipple reconstruction, the immediate operative result should be twice the desired final height. The patient should be prepared for the oversized, immediate result. The extremities of the tangent base are then connected through the apical point of the height of the design in a curvilinear fashion. The body of the skate, or ray, is then indicated with tapered dotted lines to remind the surgeon of the limits to the partial-thickness elevation of the wings (Fig. 72.1). The operative site is instilled with local anesthetic solution containing epinephrine.

The margin of the design is incised partial thickness, excepting the central one third of the tangent base. Bilateral wings are elevated at the deepest partial-thickness level, leaving behind the least amount of reticular dermis possible. This horizontal elevation continues until the dotted lines of the wing-to-body transition are reached, where the dissection shifts to vertical, incising through the remaining dermis into underlying subcutaneous tissue. The body of the skate flap must be composite and include significant soft tissue to both ensure a healthy blood supply to the flap and provide adequate volume and girth to the final nipple. These soft tissues, typically subcutaneous fat, are dissected as a deep, fingerlike extension beneath the flap, with the resulting defect a deep, V-shaped trough. Division of underlying fat is not carried all the way to the tangent base but is halted upon reaching the final nipple position, thereby maintaining a vertical blood supply to supplement the subdermal flow across the central tangent base. Division of dermis alone, however, is continued to the tangent base so the flap can achieve an unrestricted vertical posture. After prosthetic breast reconstruction, limited or absent subcutaneous tissue may remain at the reconstruction site. In such circumstances, a graft or other material may be inserted. The two wings of the skate are brought around to themselves beneath the underbelly of the composite body of the flap. A single absorbable suture is placed at the margins of the dermal defect, where the base of the nipple will fall, and includes the tips of the two wing flaps. The suture is rapidly run up the design, approximating the two wings. At the apex, the tip of the design is deepithelialized, tucked, and closed. If there is tension created during coaptation of the wings, retained fat must be removed from the central belly; such will occur routinely unless the tangent base is more than three times the diameter of the final nipple. The resulting dermal defect is closed with an additional buried suture. The exposed pattern of deep dermis is reduced or closed primarily, depending on the size of the original design and the laxity of tissues at the reconstruction site. Efforts to force the design closed will be counterproductive to the overall result. Donor-site scars closed under tension will invariably spread and present as poor bed for intradermal tattoo pigments. Such local tensions also favor late loss of nipple projection. Finally, tension at closure will flatten the very part of the breast profile where a conical fullness is desirable. Therefore, no effort is made to push primary closure to avoid the need for a small graft. As long as the graft will fall within the ultimate bed of the areola, it will be indiscernible after tattoo (Fig. 72.2A, B). Again, a well-healed, full-thickness skin graft will prove a far better recipient for tattoo than the alternative pathologic tissues of spread donor-site scars. The margins of the defect are advanced without undermining, using V-to-Y closure at the extremities of the pattern. If tension-free closure is not possible, appropriate reduction of the exposed dermis is followed by skin graft. A narrow, full-thickness graft is harvested along any portion of the mastectomy or other scar and, after defatting, is sewn in place with sutures left long for tie-over. After the nipple and graft are covered with a greasy dressing, the nipple is protected within the flanged end of a plastic syringe barrel surrounded with wet cotton. The tie-over dressing and sutures are removed at 4 days to avoid stitch marks, leaving only the fine, running monofilament suture used to secure the graft between tie-over sutures. Greasy dressing alone is continued for an additional 3 days, at which time the remaining suture is removed (Fig. 72.3).

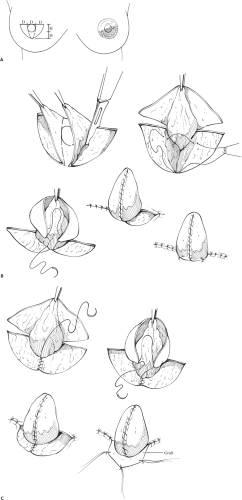

Spear Technique

Having picked the best possible site for the nipple, the design is a skate flap with a central body and two wings (Fig. 72.4A). Overall, the plan is very similar to the skate flap described by Little, but with a few modifications. Like Little, we prefer to keep any preexisting scars away from the design of the wings or body of the skate. The wings are designed with a height approximately twice the desired projection. In this design, we

intentionally do not attempt primary closure of the defect, but rather use a small, rectangular, full-thickness graft or complete random full-thickness graft mimicking the size and shape of the desired areola. The trough-shaped defect created from elevating the body of the nipple is closed primarily with a running locking suture of 4-0 Monocryl, which starts near the design apex and runs as a locking suture up to the base of the nipple and then continues and backtracks as a simple running suture back toward the apex and finishes as an intradermal stitch beyond the area of deepithelialization (Fig. 72.4B). This helps keep any knots away from the skin grafts.

intentionally do not attempt primary closure of the defect, but rather use a small, rectangular, full-thickness graft or complete random full-thickness graft mimicking the size and shape of the desired areola. The trough-shaped defect created from elevating the body of the nipple is closed primarily with a running locking suture of 4-0 Monocryl, which starts near the design apex and runs as a locking suture up to the base of the nipple and then continues and backtracks as a simple running suture back toward the apex and finishes as an intradermal stitch beyond the area of deepithelialization (Fig. 72.4B). This helps keep any knots away from the skin grafts.

Figure 72.1. The Little technique. A: Marking the skate. B: Raising the skate without skin graft. C: Raising the skate with skin graft. |

The decision to use a small, postage stamp–type graft or a full-size, round areola graft is a technical decision that depends on several items, including the easy availability of a piece of skin of appropriate size, the benefits of a graft sized as an aesthetic unit, the tightness of the skin, and the presence of scars near the nipple that might be hidden under an areola-size graft. If a full areola graft is chosen, the required circle is deepithelialized after the central trough defect is closed (Fig. 72.4C). The small, postage stamp–type grafts are sewn in place with interrupted and running absorbable sutures and covered with a special nipple protector. The full areola grafts are held in place with the additional help of a bolster dressing instead of the special nipple protector.

Star Flap

The star flap of Spear represents a modification of the design recommended by Hartrampf, itself a derivation of the skate design. As with the skate flap, there is a central composite fingerlike flap that will be elevated out of the plane of the breast (Fig. 72.5). If the final nipple is likened to a five-sided cube, the total length along its design axis will contribute to the vertical height of the superior wall of the cube, its apical wall or cap, and a portion of the height of the inferior wall. Full-thickness, tapered arms based on either side of the long axis are used to wrap around to each other, completing the lateral walls of the nipple cube and some portion of its inferior wall. Although the full height of the design, therefore, does not contribute to projection, closure of its various components is straightforward, producing a neat, cubelike package (Fig. 72.6). If flap dimensions are pushed beyond the limits of comfortable closure, however, inadequate projection of the final result follows, as well as spread and potentially hypertrophic scars at the three donor sites, limiting the success of areolar tattoo.

C-V Flap

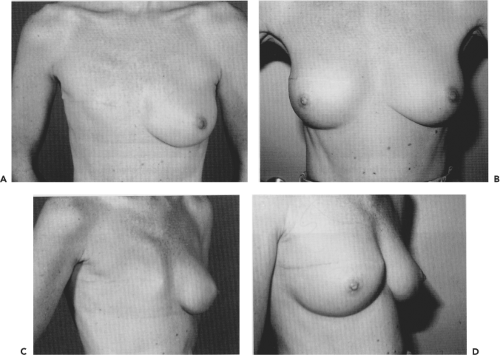

The C-V flap (6) is designed to take into account symmetry, diameter, and projection. The location is determined while in

the upright position. The flap is based on two V flaps to provide projection and a C flap to provide diameter. The design is marked in the appropriate position (Fig. 72.7A). Projection is determined by the base width of the V flaps. Typically, the bases are designed wider to account for loss of projection later. The flap is elevated, taking care not to divide the base of the flap or the attachments of the V flaps to the C flap (Fig. 72.7B). The subcutaneous tissue is thinned from the V flaps but left thick in the center of the flap. The V flaps are wrapped, and the C flap is used as a cap to complete the nipple (Fig. 72.7C). Finally, the donor sites are primarily closed (Fig. 72.7D). This flap can result in excellent initial shape and projection (Fig. 72.8A–E).

the upright position. The flap is based on two V flaps to provide projection and a C flap to provide diameter. The design is marked in the appropriate position (Fig. 72.7A). Projection is determined by the base width of the V flaps. Typically, the bases are designed wider to account for loss of projection later. The flap is elevated, taking care not to divide the base of the flap or the attachments of the V flaps to the C flap (Fig. 72.7B). The subcutaneous tissue is thinned from the V flaps but left thick in the center of the flap. The V flaps are wrapped, and the C flap is used as a cap to complete the nipple (Fig. 72.7C). Finally, the donor sites are primarily closed (Fig. 72.7D). This flap can result in excellent initial shape and projection (Fig. 72.8A–E).

Composite Nipple Graft

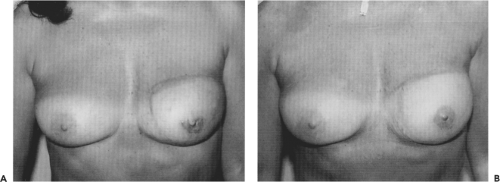

A composite graft may be taken from the contralateral nipple if it is of adequate size. The graft may be taken from either the distal tip or the lower half of the nipple (Fig. 72.9). The graft

is then sutured into place over a deepithelialized site on the reconstructed breast. The donor site is then closed either by a purse-string suture if the graft was from the tip or by turning down the inferior edge and suturing it to the areola if the lower half was used. Tattooing may be done either before or after the composite graft. In the appropriate patient this technique can result in nipples with excellent projection and size (Fig. 72.10A, B).

is then sutured into place over a deepithelialized site on the reconstructed breast. The donor site is then closed either by a purse-string suture if the graft was from the tip or by turning down the inferior edge and suturing it to the areola if the lower half was used. Tattooing may be done either before or after the composite graft. In the appropriate patient this technique can result in nipples with excellent projection and size (Fig. 72.10A, B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree