Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adolescent Dermatology: Introduction

|

Just as dermatology cannot be separated from internal medicine, pediatric dermatology is inseparable from general pediatrics. Since most dermatologists have experience and training in internal medicine but less exposure to pediatrics and neonatology, an introduction to the special issues that can arise in pediatric dermatology is presented herein. As it is impossible to discuss all of pediatric dermatology in one chapter, the focus is instead on certain methods, diseases, and issues divided by three age divisions: neonates and infants, children, and adolescents. Topics of special importance such as pediatric medication use and biopsy pitfalls are discussed. Methods to enhance success in outpatient procedures in pediatric dermatology are also reviewed.

Successful care of the pediatric patient is best achieved via comanagement with the neonatalogist, pediatrician, or primary care physician. In addition, an understanding of the parental or family situation is important. For example, children living in two households (due to divorced parents) may do best with two sets of medications, one in each home, to enhance compliance. Table 107-1 reviews ten helpful tips in practicing pediatric dermatology. As an example, if Internet access exists, patients or parents will likely search online for medical information before or after the office encounter. Parents and patients should be warned that medical information on the Internet is often inaccurate.1 It is wise to direct them to specific Internet Web sites, support groups, or pamphlets, but these resources should be reviewed before recommending them.

|

Neonates and Infants

The neonatal period is defined as the first 30 days of life. Neonatal skin diseases evolve much more rapidly than adult skin diseases, and some conditions that initially appear to be serious turn out to be trivial, whereas in others, the opposite is true. Infancy is defined as beginning after the first 30 days of life.

After birth, the neonate’s skin undergoes a series of changes in adaptation to the extrauterine environment. In utero, the skin of the fetus is protected by the vernix caseosa and is immersed in amniotic fluid. After birth, the vernix is wiped off, and the skin is exposed and adapts to the dry ambient air. For example, desquamation of the upper layers of the stratum corneum occurs normally in all infants and is believed to be a normal adaptive process.

Research regarding the maturation of the neonatal stratum corneum in neonates has produced varying results, and the question of when full barrier function is achieved is not fully answered. Barrier stabilization appears to be a dynamic process, one dependent upon a balance between different biologic and environmental parameters. Postnatal life is believed to accelerate stratum corneum maturation in premature and term infants. Parameters such as skin thickness, skin pH, and stratum corneum hydration indicate that neonatal skin is continuously adjusting to the extrauterine environment, in contrast to the adult skin, which remains in a steady state.2

In vivo studies of human skin show that infant stratum corneum and epidermis is thinner than adult skin and has higher transepidermal water loss (TEWL) rates, but infant stratum corneum has higher water content. Infant corneocytes and granular cells are smaller than adult corneocytes suggesting a more rapid cell turnover than in adults.3

Infants have an increased risk for systemic toxicity from topically applied substances. This is due in large part to the great surface area–body mass ratio in the infant. In addition, the infant’s metabolism, excretion, distribution, and protein binding of substances can be significantly different from those of an adult and add to increased risk of toxicity.4

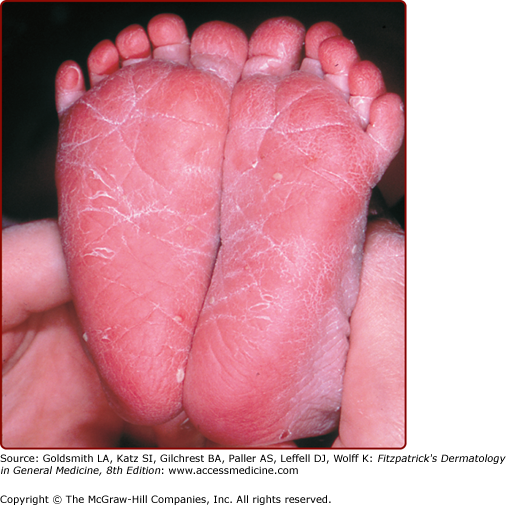

The postmature infant (>40 weeks’ gestation) typically has dry and cracked or peeling skin noted soon after birth (Fig. 107-1). Shedding of the dry peeling skin of postdates infants occurs spontaneously in the first month of life, leaving normal, healthy skin. Topical care should include moisturizers and avoidance of overbathing.

Premature infants, particularly those born before 34 weeks of gestation, have markedly decreased epidermal barrier function and an even greater surface area–body mass ratio than term infants. In addition, the immature organs of the premature infant may affect the metabolism, excretion, distribution, and protein binding of chemical agents. Local or systemic toxicity can occur in the premature infant not only from topical medications, but also soaps, lotions, or other cleansing solutions.4,5

Increased skin fragility is a hallmark of prematurity (gestational age less than 37 weeks). Epidermal and dermal injury may lead to significant cutaneous pain even with routine handling and nursing care. The premature infant is at risk for infection and sepsis from skin-associated organisms entering through breaks in the thin and fragile skin and via iatrogenic portals of entry. Sweating in the premature infant is functionally reduced and contributes to poor thermal regulation. Heat regulation is dysfunctional due to a thin subcutaneous fat layer for insulation, poor autonomic control of cutaneous vessels, and a large surface–body ratio. In the nursery, the premature infant is usually placed in a temperature and humidity-controlled isolette until the infant matures and temperature and fluid regulation stabilizes.

In the 1990s researchers reported application of petrolatum-based emollient therapy to be beneficial in hospitalized preterm infants, decreasing transepidermal water loss.6 Subsequently, various emollients and regimens have been tested in infants of variable prematurity and birthweight. Improved skin integrity consistently improved in these studies, however, a threefold increase in the incidence of systemic candidiasis was reported after emollient therapy was implemented in extremely low birthweight (≤1,000 g) premature infants in one neonatal intensive care unit.7 Another outbreak of systemic candidiasis occurred in very low birthweight neonates (≤1,500 g) in a different neonatal intensive care unit.8 A 2004 Cochrane review concluded that prophylactic application of topical ointments increased the risk for nosocomial infection and advised against their routine use in preterm infants. In contrast, randomized, controlled studies in impoverished Bangledeshi preterm neonates have demonstrated decreased mortality rates when sunflower seed oil or Aquaphor ointment was applied by massage, compared to premature infants not receiving massage or emollients.9 Until prospective, controlled trials are performed, neonates receiving petrolatum-based emollient therapy should be carefully monitored for infections, particularly those infants with birthweights less than 1,500 g.

Once at home, bathing once or twice a week in plain water is sufficient for most infants; if bathing is more frequent, moisturization with unscented, simple emollients is recommended. The face, hands, and diaper area may be cleansed daily using a small amount of a mild, unscented, pH-neutral cleanser. Well-meaning parents often bathe their infants too frequently and use a multitude of products on their infant’s skin. In addition to irritation and asteatosis, these practices may increase the risk of allergic contact dermatitis in infants. It has been estimated that the average newborn is exposed to approximately 10 skin care products in the first month of life, leading to exposure to more than 50 different chemicals ranging from mildly toxic to toxic.10 Parents should be taught that “less is best.”11

A complete history includes gestational and birth history as well as family history. Exposures during pregnancy, including medications, illicit drugs, and infectious diseases such as varicella and sexually transmitted diseases, should be reviewed. Obstetric data, including placental appearance and cultures, can be invaluable. In examining an infant, the most important element is thoroughness. Whether the infant is examined in the lap of the parent or on the examination table, all surfaces, including the creases and valleys of body folds and the diaper region (including the genitalia), deserve close examination. A vascular stain, vasoconstricted macule, or erosion can be the presenting sign of a hemangioma.12 A stray hair may later strangulate an appendage and should be removed. Infants with digital tourniquet (pseudoainhum) and clitoral tourniquet have been described.13,14 Congenital lesions of all classifications (e.g., pigmented, vascular, aplasias) warrant closer inspection to rule out associated findings. Midline lesions on the face, scalp, or spine may have central nervous system (CNS) connections and should not be biopsied without proper evaluation (see Table 107.7). The diaper area has its own unique set of problems and deserves examination at every visit.

Age Group | Lesion and Site | Diagnosis | Danger | Proper Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Newborn | Erosion or vesicle on the scalp | Aplasia cutis congenita Differential diagnosis: herpes, fetal scalp electrode trauma | Possible intracranial connection, risk of meningitis with biopsy or scraping | Protect site; do not scrape lesion or biopsy, consider ultrasound or MRI of head if a typical |

Infant | “Hair collar” sign surrounding lesion on scalp or midline lesion | Encephalocele, spina bifida occulta, meningomyelocele | Possible intracranial connection; risk of meningitis | Preoperative imaging; consider neurosurgical consultation |

Infant | Tuft of hair over midline spine | Spina bifida occulta, meningomyelocele | Possible intracranial connection; risk of meningitis | Preoperative imaging; consider neurosurgical consultation |

Infant | Preauricular “tag” | Accessory tragus | Risk of chondritis if removed by shave or snip excision or if ligated with suture37 | Appropriate closure when excised, if cartilaginous component present |

Infant or child | Mass along midline scalp, glabella, side of forehead, or other embryonic fusion plane | Dermoid cyst | Intracranial connection in up to 25% for midline dermoids; risk is higher if sinus present38; dermoids near the lateral eyebrows rarely have intracranial connections39 | Consider MRI and neurosurgical consultation |

Infant, young child | Nasal midline mass | Nasal glioma, encephalocele, or other dysraphic state Differential diagnosis: “hypertelorism,” hemangioma | Intracranial connection in 100% of encephaloceles; gliomas may extend into oropharynx or have intranasal connections38 | Consider MRI and neurosurgical consultation |

Infant, young child | Vascular mass with greatly increased warmth, often with pulsation or bruit | Arteriovenous malformation Differential diagnosis: hemangioma | Uncontrolled bleeding, problematic bony or soft tissue hypertrophy | Consider Doppler studies, MRI, and surgical consultation |

The infant is vulnerable and completely dependent on the caretakers. The social support system and family structure must be considered when implementing a medical plan. There are times when the parents’ desire for treatment may not be in the best interest of the patient.

Medical and surgical decision making for the infant is based primarily on function rather than cosmesis. For example, extraction of a natal tooth is indicated if breast-feeding is impaired; whether or not the tooth is a component of a genetic syndrome is a separate issue.

Skin conditions encountered in newborns that tend to resolve by 30 days of age are considered to be transient. They are very common and many are expected in newborns.

Caput succedaneum is subcutaneous edema over the presenting part of the head and is a common occurrence in newborns. Cephalohematoma is a subperiosteal collection of blood and is less common. Both lesions are due to shearing forces on the scalp skin and skull during labor.

Caput succedaneum is soft to palpation, and borders are ill-defined. Cephalohematoma is bounded by the suture lines of the skull and often feels fluctuant. If purpura is extensive, it can lead to hyperbilirubinemia. Congenital lymphedema or lymphatic malformations (such as in Turner syndrome) can mimic caput succedaneum. Both caput succedaneum and cephalohematoma resolve spontaneously; however, caput usually fades in 7–10 days, whereas cephalohematoma slowly resolves over several weeks.

Milia are multiple pinpoint- to 1-mm papules representing benign, superficial keratin cysts. They are seen most commonly on the nose of infants and may be present in the oral cavity as well, where they are called Epstein’s pearls. They are expected findings in the newborn and resolve spontaneously within a few weeks of life.

At least 50% of normal newborns have sebaceous gland hyperplasia (Fig. 107-2). Tiny (<1-mm) yellow macules or papules are seen at the opening of each pilosebaceous follicle over the nose and cheeks of term newborns. It is a benign condition that clears spontaneously by 4–6 months of age.

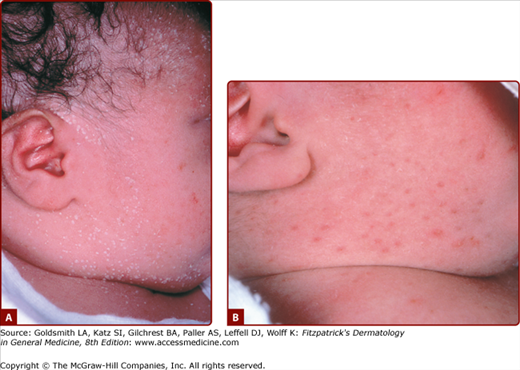

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) is an idiopathic, common condition seen in up to 75% of term newborns. It is rarely seen in premature infants. Blotchy erythematous macules 1–3 cm in diameter with a 1–4-mm central vesicle or pustule are seen in ETN (Fig. 107-3). They usually begin at 24–48 hours of age, but delayed eruption as late as 10 days of age has been documented.15 These follicular-based lesions can be located anywhere but tend to spare the palms and soles. A smear of the central vesicle or pustule contents will reveal numerous eosinophils on Wright-stained preparations. A peripheral blood eosinophilia of up to 20% may be associated, particularly in infants, with numerous lesions. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) lesions conrail neutrophils rather than eosinophils, and individual lesions heal with residual pigmentation, which is not seen in ETN. Bacterial infections, Pityrosporum folliculitis, and congenital candidiasis also may mimic ETN. Bacterial and fungal culture of lesions and Gram staining will help differentiate among these entities. ETN is benign and clears spontaneously by 2–3 weeks of age without residua.

TNPM is an idiopathic pustular eruption of the newborn that heals with tiny brown-pigmented macules (Fig. 107-4). It is less common than ETN and is more prevalent among newborns with darkly pigmented skin. Lesions are usually present at birth or shortly thereafter, but may appear as late as 3 weeks of age, as superficial vesicles and pustules, with ruptured lesions evident as collarettes of scale. Pigmented macules are also often present at birth or develop at the sites of resolving pustules or vesicles within hours or during the first day of life; occasionally babies are born with the tiny melanocytic macules, suggesting in utero vesiculation. Lesions can occur anywhere but are common on the forehead and mandibular area. The palms and soles may be involved. Smear of the vesicle or pustule contents will reveal a predominance of neutrophils with occasional eosinophils on Wright-stained preparations.16

Miliaria rubra is frequently confused with ETN and TNPM. The erythema around miliaria rubra is small in area (1–2 mm versus 20–30 mm in ETN). The central pustule of TNPM may mimic congenital candidiasis, Pityrosporum folliculitis, or bacterial folliculitis lesions. Herpes simplex should be considered if lesions are vesicular. A Gram-stained slide of the pustules of ETN or TNPM will not show organisms. A Wright-stained slide usually will show a predominance of neutrophils. TNPM is a harmless condition that requires no treatment. The pustules usually disappear within 5–7 days of age, leaving residual pigmented macules that resolve over 3 weeks to 3 months.

Mottling is a blotchy or lace-like pattern of dusky erythema over the extremities and trunk of neonates that occurs with exposure to cold air. Virtually all babies demonstrate mottling at some time during the newborn period due to immaturity of the autonomic control of the cutaneous vascular plexus. This physiologic mottling disappears on rewarming, differentiating it from cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and livedo reticularis. Normal mottling resolves spontaneously by 6 months of age.

Harlequin color change is a rare vascular phenomenon occurring in low-birthweight infants. When the infant is placed on one side, an erythematous flush with a sharp demarcation at the midline develops on the dependent side, and the upper half of the body becomes pale. The color change usually subsides within a few seconds of placing the baby in the supine position but may persist for as long as 20 minutes. The exact mechanism of this unusual phenomenon is not known, but it may be due to immaturity of autonomic vasomotor control. Harlequin color change is seldom seen after 10 days of age.

Sucking blisters may be present at birth as the result of intrauterine sucking, but are more commonly seen during the first weeks of life. Sucking blisters are usually solitary, intact oval or linear blisters, erosions, or drying crusts, arising on noninflamed skin of the dorsal-radial aspect of forearms, wrists, or fingers or on the upper lip. They resolve within a few days. If the affected extremity is brought up to the infant’s mouth, the infant will often commence sucking at the site, confirming the diagnosis. Herpesvirus infection is often considered when sucking blisters are encountered, but lesions of Herpes simplex infection are grouped vesicles occurring on an erythematous base or punched out, hemorrhagic erosions.

Neonatal acneiform facial lesions usually develop within the first 30 days of life and are estimated to occur in 50% of newborns (Fig. 107-5). This benign eruption appears to be hormonally mediated (see Chapter 80) and has been attributed to overgrowth of Malassezia sp., and termed “benign neonatal cephalic pustulosis.”17 Most cases resolve spontaneously, but the eruption can be treated topically with ketoconazole, benzoyl peroxide, or erythromycin. True neonatal acne is probably much less common than benign cephalic pustulosis and can be distinguished by the presence of comedonal lesions. Similarly, infantile acne usually shows true comedones, sometimes with papules, pustules, and even cysts. An example of infantile acne is seen in Figure 107-6.

Telogen effluvium occurs frequently in newborns and is often overlooked. The hair loss may be gradual or sudden, and may occur as soon as the first few days of life, with the telogen hairs shed by 3–4 months of age. No treatment is indicated as spontaneous resolution is the rule.

A transient circumscribed patch of nonscarring alopecia develops at the occiput in many infants. Thought to be due to a combination of physiologic telogen effluvium and localized pressure from lying in the supine position, occipital alopecia spontaneously resolves.

Triangular temporal alopecia is a form of nonscarring hair loss noted at 2–5 years of age as a triangular-, oval-, or lancet-shaped area of alopecia at the frontotemporal scalp. Often, a thin row of hair separates the affected area from the forehead. The terminal hairs are replaced by vellus hair. The condition is often mistaken for alopecia areata; however, distinguishing features include the typical location and shape, the presence of vellus hairs, and the absence of exclamation point hairs or histologic findings of alopecia areata. There is no known treatment, and the condition persists unchanged. However, triangular temporal alopecia is benign and will not expand.

Alopecia areata occurs in all ages (see Chapter 88). All forms of alopecia areata occur in infants and children (patchy, universalis, etc.), with the same disease presentation and treatment challenges as in adults. Onset at younger than 2 years of age is estimated to occur in 1%–2% of alopecia areata patients; however, it may be under-recognized and more common. Several cases of congenital alopecia areata have been documented. Early onset is considered to be a poor prognostic marker. Total alopecia during the first year of life after having hair at birth should be distinguished from genetic disorders, such as congenital atrichia with papular lesions and vitamin D resistance.

Tinea capitis can occur at any age, including infancy (see Chapter 188). Hair loss associated with scaling, broken hairs, pustules, or black dots should prompt a potassium hydroxide scraping and fungal culture to confirm the diagnosis. Just as in older children, Trichophyton tonsurans is the most common dermatophyte, and oral griseofulvin is the treatment of choice. Tinea capitis and fungal infections are discussed in Chapter 188.

Birthmarks represent an excess of one or more of the normal components of skin per unit area: blood vessels, lymph vessels, pigment cells, hair follicles, sebaceous glands, epidermis, smooth muscle, collagen, or elastin. Although most birthmarks are of little medical or psychosocial consequence, the social and cultural impact of a disfiguring birthmark should not be underestimated, from both the patient’s and the parents’ perspectives.19 The age-old theory of maternal imprinting is still widely accepted in many countries, including the United States, and the mother may be subtly or actively blamed for congenital conditions in the newborn. With selective photothermolysis offered by lasers and advances in surgical and topical therapies, therapeutic options are increasing.

The two most common birthmarks are the nevus simplex (see Chapter 172) and Mongolian spots (see Chapter 122). Nevus simplex (also known as salmon patch, nevus flammeus, angel’s kiss, or stork bite) represents a capillary malformation of the skin. It occurs most commonly on the glabella, upper eyelids, and nuchal area. Nevus simplex appears with high frequency in all races, occurring in 70% of white infants and 59% of black infants. Mongolian spots, which represent collections of dermal melanocytes, are seen in 80%–90% of infants of color but in only 5% of white infants.20,21 Solitary café-au-lait macules are extremely common and benign, however, the appearance of multiple café-au-lait macules raises the possibility of neurofibromatosis type 1 (see Chapter 141). Other common birthmarks are listed in Table 107-2.

|

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common tumors of infancy. They must be differentiated from vascular malformations and other vascular anomalies. Hemangiomas are discussed in detail in Chapter 126.

Both types of lymphatic malformations, microcystic (lymphangiomas) and macrocystic (cystic hygromas), are discussed in Chapter 172.

Selected dermatoses of the neonate are discussed in the following sections. Table 107-3 lists differential diagnoses for selected cutaneous conditions encountered in neonates and infants.

|

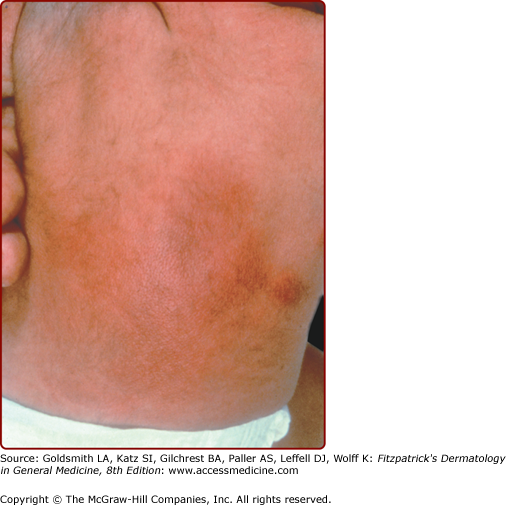

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita is characterized by persistent coarse cutis marmorata, telangiectasia, and sometimes associated underlying cutaneous atrophy and ulceration (Fig. 107-7). Its incidence is sporadic, and its etiology is obscure. Theories of vascular malformation are currently favored. Diagnosis is usually evident on clinical examination. Usually a lower extremity is involved, but location on the trunk or upper extremity is not uncommon. A multitude of associated anomalies can occur, including limb asymmetry, hemangiomas, other vascular birthmarks, pigmented nevi, and aplasia cutis congenita (ACC). However, the majority of patients have a good prognosis, with half demonstrating improvement of the mottled appearance over the first 2 years.22

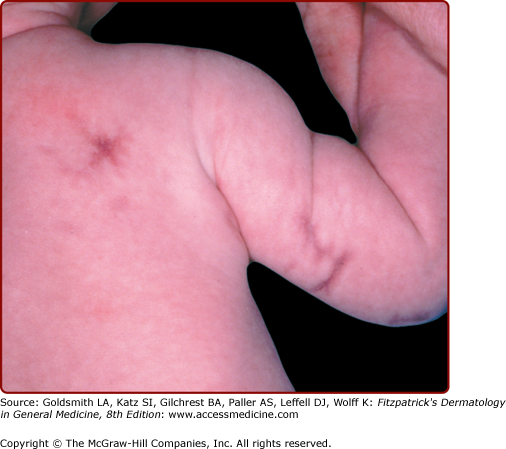

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by firm, circumscribed, reddish or purple subcutaneous nodules or plaques that appear over the back, cheeks, buttocks, arms, and thighs (Fig. 107-8; see Chapter 70). The lesions usually begin within the first 2 weeks of life and resolve spontaneously over several weeks.23

Sclerema is diffuse hardening of the skin in a sick premature newborn that is now rare because of improved neonatal care. The onset is characteristically after 24 hours of age. The skin feels hard and immobile and looks yellow and shiny. The trunk is always involved. Severely ill premature newborns that have suffered sepsis, hypoglycemia, metabolic acidosis, or other severe metabolic abnormalities are at risk. Biopsy sections show edema of fibrous septa surrounding fat lobules, but no fat necrosis, differentiating it from subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. The etiology of this rare condition is unclear, and infant mortality is high.

ACC represents a failure of skin to fully develop, most often on the scalp, and less commonly elsewhere (Fig. 107-9). It is often an isolated finding, but a multitude of associated conditions have been described. ACC has no single underlying cause. Some cases may represent a forme fruste of a neural tube defect.24 In the most common form of ACC, oval, sharply marginated atrophic macules are seen on the midline of the posterior scalp. They are usually solitary, but may be multiple. Aplasia cutis is always hairless, and may appear vesicular, ulcerated, or covered by a thin epithelial membrane. When healed, lesions are usually atrophic scars, but sometimes develop a keloidal scar. Epidermis, dermis, and fat all may be missing, or a single layer may be absent. Lesions may range from a few millimeters to many centimeters in diameter. Lesions at birth of epidermolysis bullosa (see Chapter 62) may resemble ACC, especially on one or both legs. Scalp ulcers at birth of aplasia cutis may be mistaken for obstetric trauma. Other forms of congenital circumscribed hair loss should be considered. Midline blisters or erosions should not be biopsied, scraped for herpes cultures, or otherwise traumatized. After a careful examination to rule out associated malformations, ACC is treated conservatively to allow healing. Surgical revision of the scar later in childhood or adolescence can be done electively to improve cosmesis.

Figure 107-9

Two infants with aplasia cutis congenita. A. Scalp erosions grouped at the vertex scalp. Scraping or biopsy is contraindicated. B. An atrophic, well-circumscribed round patch with visible capillaries on the scalp of an infant. (A used with permission from 1991 Yale Resident Photograph Collection.)

The “hair collar sign” is a ring of darker and/or coarser terminal hairs on the scalp, typically surrounding ACC, dermoid cyst, encephalocele, meningocele, or heterotopic brain tissue.25 The hair collar sign itself is a marker of cranial dysraphism and its presence, like aplasia cutis, mandates careful examination of the infant, particularly of midline structures and fusion planes.

A specific form of iatrogenic anetoderma (see Chapter 67) has been described in extremely premature infants (born at 24–30 weeks’ gestation) with very low birthweight and prolonged neonatal intensive care hospitalization.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree